Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Evaluating the Theoretical Content of Online Physical Activity Information for People with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Background: Physical activity can aid people with multiple sclerosis (MS) in managing symptoms and maintaining functional abilities. The Internet is a preferred source of physical activity information for people with MS and, therefore, a method for the dissemination of behavior change techniques. The purpose of this study was to examine the coverage and quality of physical activity behavior change techniques delivered on the Internet for adults with MS using Abraham and Michie's taxonomy of behavior change techniques.

Methods: Using the taxonomy, 20 websites were coded for quality (ie, accuracy of information) and coverage (ie, completeness of information) of theoretical behavior change techniques.

Results: Results indicated that most websites covered a mean of 8.05 (SD 3.86, range 3–16) techniques out of a possible 20. Only one of the techniques, provide information on behavior–health link and consequences, was delivered on all websites. The websites demonstrated low mean coverage and quality across all behavior change techniques, with means of 0.64 (SD 0.67) and 0.62 (SD 0.37) on a scale of 0 to 2, respectively. However, coverage and quality improved when websites were examined solely for the techniques that they covered, as opposed to all 20 techniques.

Conclusions: This study, which examined quality and coverage of physical activity behavior change techniques described online for people with MS, illustrated that the dissemination of these techniques requires improvement.

Physical activity has the potential to help in the management of symptoms resulting from multiple sclerosis (MS) and the maintenance of functional abilities.1 2 Despite these benefits, people with MS have low physical activity participation,3 4 which is associated with increased risk of secondary conditions such as cardiovascular disease.5 Thus, promoting physical activity behavior change among people with MS is imperative, as physical activity participation results in a number of MS-specific physical and psychological advantages.1

The use of behavior change techniques is a strategy that may help promote physical activity among people with MS.4 These techniques are based on behavior change theories and designed to target specific psychosocial constructs that influence health behavior. Abraham and Michie6 created a taxonomy for assessing the use of these techniques (see Appendix 1). This taxonomy has been employed in evaluating a variety of health and physical activity topics and modes of delivery, including an examination of the theoretical content of physical activity brochures7 and the promotion of health behavior change on the Internet.8 The use of behavior change techniques holds promise for the promotion of physical activity among people with MS. A recent review9 has highlighted many of the constructs on which these techniques are based—including self-efficacy (ie, situation-specific self-confidence), outcome expectations (ie, an individual's belief in the positive and negative outcomes of physical activity), and goal setting—as key determinants of physical activity for people with MS.

Websites serve as a platform for physical activity interventions and presentation of behavior change techniques. The Internet is the first source of health information accessed by people with MS,10 with 82% of patients with MS searching for information online before initial consultations with physicians.11 In this population, the Internet is also a preferred source for physical activity information.12 Online resources also have a role in clinical practice. They have potential to serve as a) a theory-based resource for health-care providers, who often lack knowledge to prescribe and promote physical activity and the resulting health benefits among their patients; and b) an educational tool to which patients can be referred.13 Therefore, behavior change techniques targeting physical activity behaviors on websites may reach large numbers of people with MS, either directly through an individual's own research or indirectly through their health-care provider.

It is unknown whether physical activity behavior change techniques are being employed by health-related websites targeting people with MS, nor is it known whether the information disseminated is of high quality—an important concern of people with MS.10 12 To our knowledge, only one evaluation of MS websites has been conducted, in which the authors concluded that the overall quality of MS information delivered online was variable.14 There has been no examination of the specific content of MS websites, such as physical activity information, nor has there been an evaluation employing a taxonomy of behavior change techniques. This research gap must be filled in order to determine whether the information being provided to people with MS targets essential determinants of behavior change, and will be successful in promoting physical activity. Furthermore, the use of a taxonomy will permit researchers to provide recommendations of methods that can be used to improve online physical activity promotion for adults with MS. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the coverage and quality of physical activity behavior change techniques on the Internet for adults with MS using Abraham and Michie's taxonomy of behavior change techniques.6

Methods

Selection of Websites

In January 2013, a search was conducted on the Google and Yahoo search engines for websites containing physical activity information for people with MS. Websites were included if they 1) contained any MS-specific exercise, physical activity, or sport-related information; 2) were created by an organization or a government-affiliated agency; 3) were written in English; and 4) were displayed on the first four pages of search results. We limited the search to four result pages based on previous studies that considered this to be a conservative estimate of the number of result pages viewed by the average Internet user.15 16 Websites directed at health professionals were excluded.

Search Procedure

A list of eligible websites was compiled by entering the following terms in the search engines: (“MS” OR “multiple sclerosis”) AND (“exercise” OR “physical activity” OR “sport” OR “fitness”). Four researchers conducted the search independently using four different computers in order to reduce bias based on a computer's previous search history. Following a discussion comparing the results from each researcher, a total of 20 websites that met the eligibility criteria were included (Appendix 2).

Website Characteristics

Eligible websites were assessed using the European Commission Quality Criteria for Health Related Websites.17 According to these criteria, websites must have the following indicators: transparency and honesty, authority, accountability, accessibility, updating of information, and privacy and data protection17 (see Appendix 3 for criteria and item definitions). Each indicator contains items that, when present, are indicative of high quality in health-related websites. Items were coded as being either present = 1 or absent = 0, based on pre-established operational definitions. The proportion of websites meeting each of the indicators of quality was calculated using frequency counts and percentages.

Because of the importance of tailoring physical activity information to the individual with MS,12 websites were also coded for using images of people with MS, as well as targeting different functional abilities, people recently diagnosed, people in relapse, people in remission, gender, and specific geographic locations. In addition, websites were coded for providing information on physical activity (ie, types of physical activity, frequency, intensity, and duration) and physical activity guidelines. These items were also coded as being either present = 1 or absent = 0.

Coverage and Quality of Behavior Change Techniques

To examine the behavior change techniques used in health-related websites for people with MS, an adapted version of the taxonomy of behavior change techniques developed by Abraham and Michie6 was utilized (Appendix 1). Of the 26 behavior change techniques originally identified for health interventions, 21 were considered suitable for information found on the Internet. The behavior change techniques “providing feedback on performance,” “providing contingent rewards,” “agreeing on a behavioral contract,” “use of follow-up prompts,” and “motivational interviewing” were excluded based on limitations of noninteractive websites that prevent the proper application of these techniques. Furthermore, the behavior change techniques “providing information about the behavior–health link” and “providing information on consequences” were collapsed into a single item for coding clarity, as both techniques target outcome expectancies, a component of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Integrated-Behavioral Model.18 This resulted in 20 behavior change techniques to examine on each website.

The coverage and quality of each behavior change technique was assessed. The coverage of behavior change techniques was coded as having no coverage = 0, minimal coverage = 1, or sufficient coverage = 2. Operational definitions for no, minimal, and sufficient coverage were adapted from a previous study examining health information on the Internet.19 A behavior change technique was coded as having no coverage if no information pertaining to this technique was provided on the website. If there was a superficial discussion of a particular behavior change technique, coverage was considered to be minimal. However, if there was ample discussion about the behavior change technique, coverage was considered sufficient. These codes were summed and divided by the number of behavior change techniques to obtain the mean for coverage, with higher numbers representing higher coverage.

Quality was measured to determine whether the behavior change techniques were used appropriately, meaning that the techniques were reflective of the needs of people with MS. An adapted version of the brief DISCERN scale20 was used to determine the quality of behavior change techniques present on the selected websites. Quality was coded as low = 0, medium = 1, or high = 2 based on pre-established operational definitions that captured clarity, accuracy, and relevance. Theoretically based information that was clear, accurate, and relevant was coded as high quality, while information that partially fulfilled or did not fulfill these criteria was coded as medium and low quality, respectively. These codes were summed and divided by the number of behavior change techniques to obtain the mean for quality, with higher numbers representing higher quality.

Interrater Reliability

To establish interrater reliability, two websites were randomly chosen and coded independently by four raters. Codes were then compared and interrater reliability was computed. A kappa of 0.57 (P < .05) was obtained, indicating moderate agreement.21 This level of agreement was deemed acceptable, and the remaining websites were coded by two of the four raters, with the average reliability achieved being 0.57 (P < .05). In cases where there was no initial agreement on the website codings (eg, disagreement on the presence of a technique or the coverage and quality of a technique), consensus was reached following a discussion.

Statistical Analyses

To examine the proportion of websites presenting each behavior change technique, frequencies and percentage distributions were computed. These were first calculated for each behavior change technique across all websites. Because it may not be feasible for a website to cover all 20 techniques, a second analysis was conducted examining coverage and quality solely on the basis of the behavior change techniques utilized on the website (ie, a website scoring 0 [no coverage] for a particular technique was excluded from the descriptive statistics for that particular technique). The analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 18 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Website Search

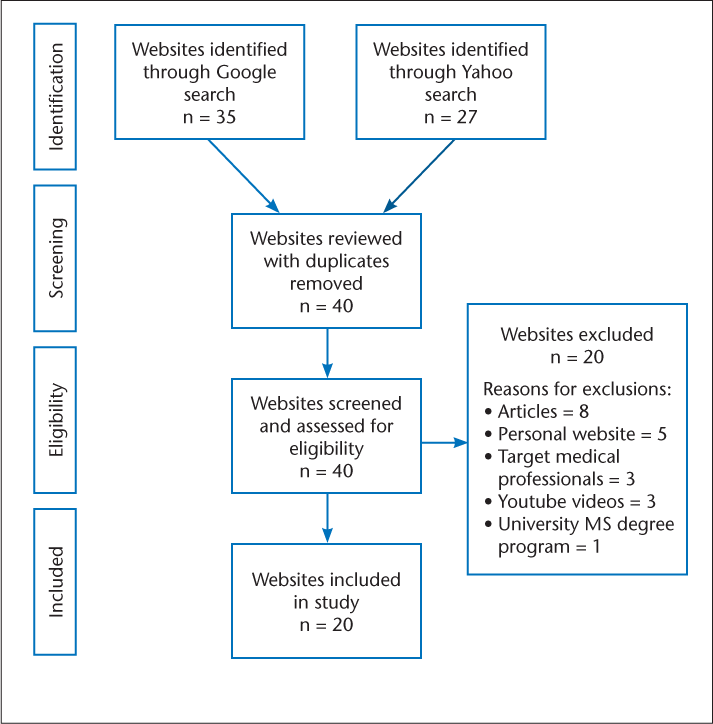

The initial search on both Google and Yahoo yielded a combined total of more than 2 million hits. Each link found on the first four pages of the search results was reviewed, resulting in 62 links (35 from Google and 27 from Yahoo). Of the 27 websites found using Yahoo, 22 were replications from the Google search. In total, 40 distinct websites were screened using the inclusion criteria, of which 20 were included in this study (Figure 1). Specific details regarding the websites can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Website selection

Website Characteristics

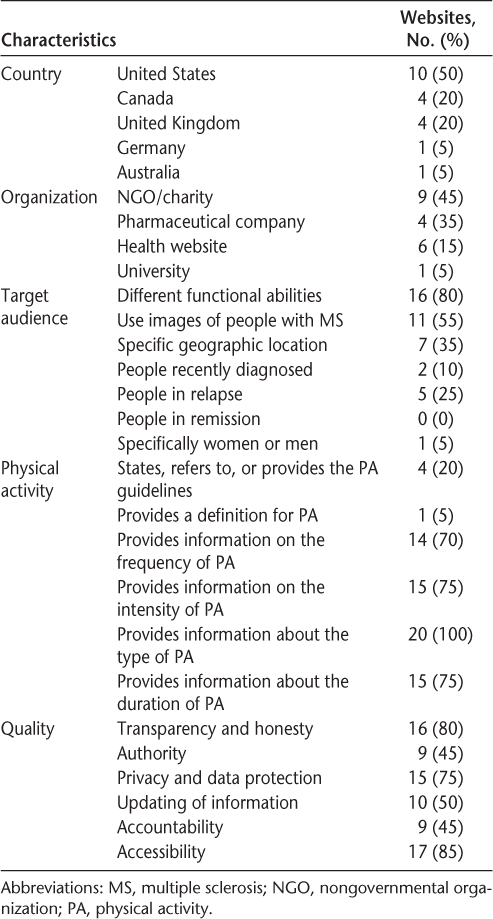

None of the websites fulfilled all six indicators from the European Commission Quality Criteria for Health Related Websites.17 The majority of websites fulfilled the transparency and honesty indicator (80%), as well as the accessibility (85%) and privacy and data protection (75%) indicators. Half of the sites fulfilled the updating of information indicator (50%), while less than half satisfied the accountability (45%) and authority (45%) indicators. The characteristics of the websites are presented in Table 1.

Website characteristics

The physical activity information presented on the websites examined mainly focused on the types of physical activities possible for people with MS, with all websites providing this information. The majority of the websites provided information about the suggested frequency (70%), intensity (75%), and duration (75%) of physical activities for people with MS. A small percentage of websites (20%) presented MS physical activity guidelines, and only one website provided a definition for physical activity (5%). The highest proportion of the websites belonged to nongovernmental (NGO) or charitable organizations (45%), half were from the United States (50%), and most used images of people with MS (55%) and targeted people with different functional abilities (80%). Less than half of the websites targeted people in a specific geographic location (35%), people recently diagnosed (10%), people in relapse (25%), or a specific gender (5%). None of the websites targeted people in remission.

Behavior Change Techniques

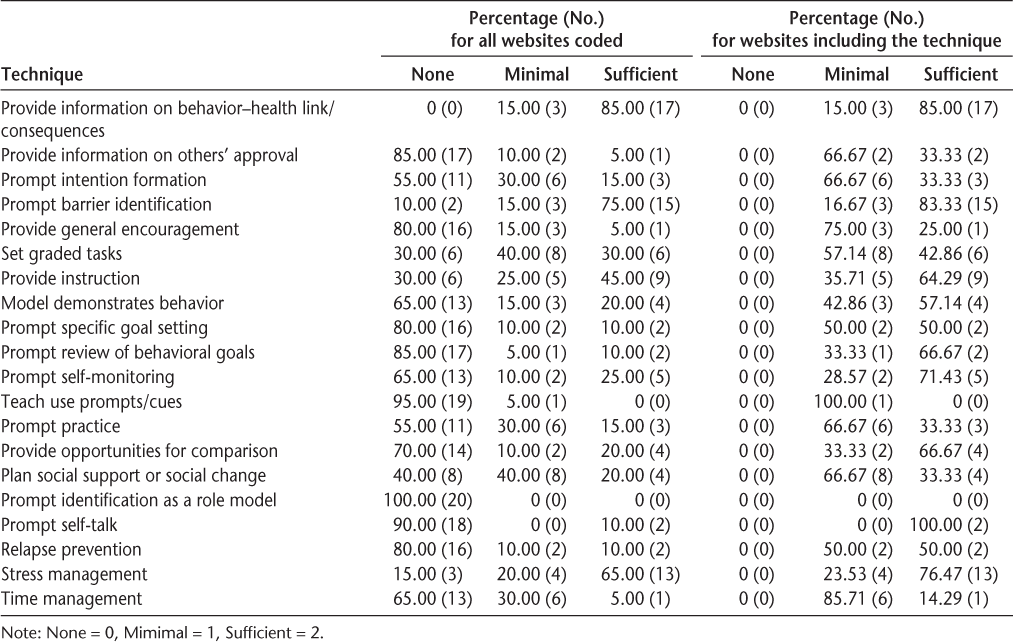

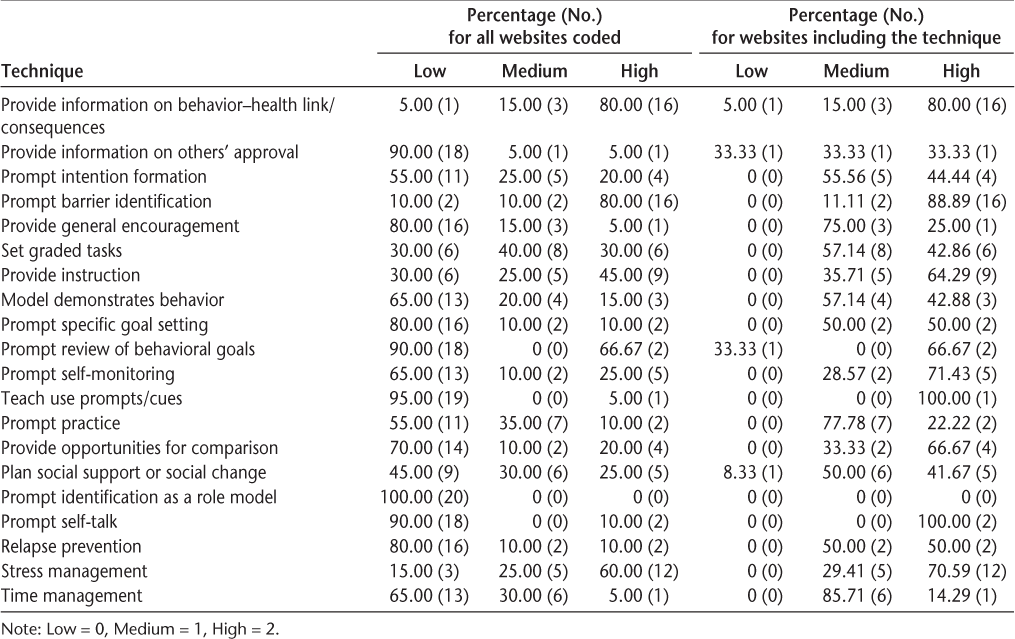

The website mean score for technique coverage was 0.64 (SD 0.67), and the mean score for technique quality was 0.62 (SD 0.37), with a maximum possible mean of 2. These results indicate that the coverage and quality of behavior change techniques are minimal and low, respectively, when evaluating the websites on all 20 behavior change techniques. In the secondary analysis considering only websites that covered a particular technique, coverage and quality means improved to 1.53 (SD 0.22) and 1.51 (SD 0.24), respectively. While the use of all techniques is minimal and the quality of information provided on all the techniques in the taxonomy is low, when examining websites solely on the basis of the techniques that they employed rather than all techniques, their performance is more promising, indicating minimal to sufficient coverage and medium to high quality.

Most websites covered a mean of 8.05 techniques (SD 3.86) out of a possible 20, with a range of 3 (n = 3) to 16 (n = 1) techniques covered by each website. The behavior change technique “provide information about the behavior–health link and consequences” was present in all websites. However, only 85% of websites provided sufficient coverage of this technique, while 80% of the information was of high quality. The second most frequent behavior change technique was “prompt barrier identification,” with 90% of websites utilizing this technique. Among the websites that used this technique, 16.67% had minimal coverage and 83.33% had sufficient coverage; 11.11% had medium quality and 88.89% had high quality. The third most frequent behavior change technique was “stress management,” with 85% of websites employing it. Of the websites covering stress management, 23.53% had minimal coverage and 76.47% sufficient coverage; 29.41% medium quality and 70.59% high quality.

The behavior change techniques with the lowest coverage and quality percentages across websites were “prompt self-talk,” “teach to use prompts or cues,” and “prompt identification as a role model.” “Prompt self-talk” was covered by only 10% of the websites. When employed, it was sufficiently covered (100%) and had high quality (100%). “Teach to use prompts or cues” was covered by only one website (5%). When employed, it was covered minimally (100%) but with high quality (100%). None of the websites used the “prompt identification as a role model” technique to promote behavior change. The coverage and quality percentages of the behavior change techniques used across websites are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Coverage of behavior change techniques (n = 20)

Quality of behavior change techniques (n = 20)

Discussion

The purpose of the current research was to examine the quality and coverage of physical activity behavior change techniques on the Internet for adults with MS. On average, websites covered less than half of the behavior change techniques identified in Abraham and Michie's taxonomy.6 Therefore, mean values were low for both coverage and quality of all of the physical activity behavior change techniques. However, it may not be feasible for a website to cover all the recommended behavior change techniques. As a result, a further examination of the websites solely on the basis of the techniques that they employed demonstrated improved quality and coverage but remained less than optimal. These findings demonstrate the need to enhance the dissemination of all the taxonomy's behavior change techniques on the Internet to support the adoption of physical activity among people with MS.

The most prominent behavior change technique employed was “provide information about the behavior–health link and consequences,” with the majority of websites providing information of medium to high quality. This technique targets the construct of outcome expectancies and was presented by highlighting the benefits of engaging in physical activity and the consequences of inactivity. This finding differs from that of a similar study7 that showed lower usage of this technique in physical activity brochures targeting the general population. Although the positive beliefs associated with physical activity in the general population are widely accepted, this may not be the case among people with MS, which may affect their decisions regarding activity.22 Therefore, this technique must continue to be a focus of health-related websites in order to convince people with MS of the importance of being active.

“Prompt identification of barriers” was the second most presented technique, with the majority of websites providing sufficient coverage and high quality. To fulfill criteria for this technique, websites had to identify barriers to physical activity and provide ideas on how these barriers could be overcome. Again, this contrasts with the analysis of physical activity brochures, in which barrier identification and overcoming barriers were presented significantly less frequently than recommendations for physical activity.7 However, this finding is consistent with literature that has noted that individuals with MS report more barriers to being active.23 This higher number of barriers is likely due to the fact that people with MS must deal with MS-specific barriers (eg, adapting physical activity to level of functional ability) in addition to those faced by the general population.22 24 As a result, individuals must put substantial effort into determining how to identify and overcome barriers. Continual focus on this technique is essential for behavior change and physical activity participation.

“Stress management” was the third most common behavior change technique. This required websites to present techniques to reduce anxiety and stress, and physical activity was often presented as a method of stress management. When utilized, this technique was sufficiently covered and had high quality. Although it is unknown if a direct relationship between stress and physical activity exists in people with MS, studies have indicated that the presence of MS symptoms is negatively associated with physical activity.25 As stress management may play a role in symptom management,26 it can be considered valuable content to include on physical activity promotion websites for people with MS.

Our findings demonstrate that while websites targeting people with MS are utilizing some important techniques, they are not advocating other behavior change techniques that have been demonstrated to effectively increase intentions to be active and to promote physical activity behavior change, such as adjusting attitudes, planning, self-monitoring, and building self-efficacy.3 24 Furthermore, when employed, these latter techniques are lacking in coverage and quality, thereby decreasing their potential effectiveness and demonstrating a gap in knowledge dissemination. Overall, these results highlight critical weaknesses in MS health-related websites' potential to strengthen physical activity intentions and promote physical activity behavior, essential aspects that must be improved for websites to be an effective platform for the delivery of behavior change information.27

According to health behavior theories, behavioral intentions tend to predict behavior.28 However, these behavioral intentions do not always translate to behavior, forming what is known as the “intention–behavior gap.”27 28 Researchers attribute the existence of this gap to two main factors. First, researchers must explore determinants of physical activity behavior beyond intentions. Second, if targeting intentions, it is essential to implement strategies that will help turn intentions into behavior.29–31 For a complex behavior like physical activity, the behavior change techniques that form the taxonomy, such as action and coping planning, can be presented on the Internet and have the potential to close this gap, strengthening the power of health-related websites.27 31 This highlights the importance of their dissemination, which is especially critical for people with MS, who are typically inactive27 and for whom the potential benefit of using these behavioral strategies to help increase physical activity behavior has been highlighted.9

Interventions designed to promote physical activity online for people with MS have demonstrated that behavioral strategies such as goal setting, building task self-efficacy, and self-monitoring are effective in increasing physical activity among people with MS, and that these strategies can be successfully delivered online.32–34 Therefore, increasing the coverage and quality of these behavior change techniques and presenting them alongside outcome expectations, barrier information, and stress management on websites providing physical activity information for people with MS may be beneficial. Including these strategies should improve the utility of health-related websites for people with MS by increasing their likelihood of becoming active. Furthermore, efforts should be made, by both researchers and practitioners, to ensure that information available on websites is updated regularly to reflect the most recent research available.

This study is not without limitation. As the taxonomy that was used to code the websites was created for interventions,6 adaptations had to be made to correspond to the context of a website. However, this limitation was mitigated through a critical revision process to ensure that the definitions were interpreted similarly by each of the coders, and that the understanding of the techniques from the taxonomy was not altered. Strengths of this study include the use of four trained coders who coded the websites in different pairs to reduce bias, as well as the critical review process utilized to create the coding scheme. Furthermore, the current study advanced knowledge of how these websites can be modified and improved to better influence physical activity behavior change among people with MS.

To our knowledge, no previous research has examined behavior change techniques for physical activity delivered to people with MS on the Internet. Understanding the physical activity behavior change content of websites is important for researchers examining the dissemination of behavior change techniques, and also for clinicians, who must be cautious to recommend only websites rich in theoretical content. This study demonstrated that although some beneficial behavior change techniques are provided on the Internet for people with MS, other key techniques are either poorly presented or not utilized. Therefore, health-related websites could be altered to better reflect current research and improve support for people with MS aiming to become active, providing a theory-based resource that clinicians can turn to in order to promote physical activity and the resulting health benefits to people with MS.

PracticePoints

Health-related websites delivering physical activity information for people with MS lack coverage of key behavior change techniques.

The dissemination of physical activity behavior change techniques to people with MS online requires quality improvements.

Information delivered online must include reference to evidence-based techniques that have demonstrated success for physical activity behavior change among people with MS.

References

Latimer-Cheung AE, Pilutti LA, Hicks AL, et al. The effects of exercise training on fitness, mobility, fatigue, and health related quality of life among adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review to inform guideline development. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:1800–1828.e3.

Motl RW, Pilutti LA, Sandroff BM, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized controlled, clinical trial investigating a comprehensive exercise stimulus for improving mobility disability outcomes in persons with multiple sclerosis. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013; 35: 151–158.

Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 459–463.

Sandroff BM, Dlugonski D, Weikert M, Suh Y, Balantrapu S, Motl RW. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: new insights regarding inactivity. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012; 126: 256–262.

Motl RW, Fernhall B, McAuley E, Cutter G. Physical activity and self-reported cardiovascular comorbidities in persons with multiple sclerosis: evidence from a cross-sectional analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2011; 36: 183–191.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008; 27: 379–387.

Gainforth HL, Barg CJ, Latimer AE, Schmid KL, O'Malley D, Salovey P. An investigation of the theoretical content of physical activity brochures. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2011; 12: 615–620.

Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the Internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010; 12:e4.

Ellis T, Motl RW. Physical activity behavior change in persons with neurologic disorders: overview and examples from Parkinson disease and multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2013; 37: 85–90.

Marrie RA, Salter AR, Tyry T, Fox RJ, Cutter GR. Preferred sources of health information in persons with multiple sclerosis: degree of trust and information sought. J Med Internet Res. 2013; 15:e67.

Hay MC, Strathmann C, Lieber E, Wick K, Giesser B. Why patients go online: multiple sclerosis, the Internet, and physician-patient communication. Neurologist. 2008; 14: 374–381.

Sweet SN, Perrier MJ, Podzyhun C, Latimer-Cheung AE. Identifying physical activity information needs and preferred methods of delivery of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2013; 35: 2056–2063.

Cullen RJ. In search of evidence: family practitioners' use of the Internet for clinical information. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002; 90: 370–379.

Harland J, Bath P. Assessing the quality of websites providing information on multiple sclerosis: evaluating tools and comparing sites. Health Informatics J. 2007; 13: 207–221.

Jansen BJ, Spink A. How are we searching the World Wide Web? A comparison of nine search engine transaction logs. Inf Process Manag. 2006; 42: 248–263.

Jetha A, Faulkner G, Gorczynski P, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Martin Ginis KA. Physical activity and individuals with spinal cord injury: accuracy and quality of information on the Internet. Disabil Health J. 2011; 4: 112–120.

Commission of the European Communities Brussels. eEurope 2002: Quality Criteria for Health Related Websites. J Med Internet Res. 2002;4:E15. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4.3.e15.

Montaño DE, Kasprzyk D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008:67–69.

Nilsson-Ihrfelt E, Fjallskog ML, Blomqvist C, Ahlgren J, Edlund P, Hansen J. Breast cancer on the Internet: the quality of Swedish breast cancer websites. Breast. 2004; 13: 376–382.

Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Cochand S, et al. Brief DISCERN, six questions for the evaluation of evidence-based content of health-related websites. Patient Educ Couns. 2009; 77: 33–37.

Hallgren KA. Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: an overview and tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2012; 8: 23–34.

Kayes NM, McPherson KM, Schluter P, Taylor D, Leete M, Kolt GS. Exploring the facilitators and barriers to engagement in physical activity for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2011; 33: 1043–1053.

Stroud N, Minahan C, Sabapathy S. The perceived benefits and barriers to exercise participation in persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2009; 31: 2216–2222.

Shirazipour CH, Motl RW, Martin Ginis KA, Latimer-Cheung AE. A systematic review of qualitative studies examining psychosocial constructs associated with physical activity participation among people with multiple sclerosis. Poster presented at: 35th Annual Meeting and Scientific Sessions of the Society of Behavioral Medicine; April 23–26. 2014; Philadelphia, PA.

Motl RW, McAuley E. Symptom cluster as a predictor of physical activity in multiple sclerosis: preliminary evidence. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009; 38: 270–280.

Buljevac D, Hop WCJ, Reedeker W, et al. Self reported stressful life events and exacerbations in multiple sclerosis: prospective study. BMJ. 2003; 327:646.

Sniehotta FF. Towards a theory of intentional behaviour change: plans, planning and self-regulation. Br J Health Psychol. 2009; 14: 261–273.

Schwarzer R. Modeling health behaviour change: how to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Appl Psychol Int Rev. 2008; 57: 1–29.

Rhodes RE. Bridging the physical activity intention-behaviour gap: contemporary strategies for the clinician. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013; 39: 105–107.

Rhodes RE, Dickau I. Moderators of the intention-behavior relationship in the physical activity domain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2013; 47: 215–225.

Scholz U, Schüz B, Ziegelmann JP, Lippke S, Schwarzer R. Beyond behavioural intentions: planning mediates between intentions and physical activity. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(Pt 3):479–494.

Dlugonski D, Motl RW, Mohr DC, Sandroff BM. Internet delivered behavioral intervention to increase physical activity in persons with multiple sclerosis: sustainability and secondary outcomes. Psychol Health Med. 2012; 17: 636–651.

Motl RW, Dlugonski D. Increasing physical activity using a behavioral intervention. Behav Med. 2011; 37: 125–131.

Motl R, Dlugonski D, Wójcicki TR, McAuley E, Mohr DC. Internet intervention for increasing physical activity in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011; 17: 116–128.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.