Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Direct and Indirect Care of Patients With Multiple Sclerosis: Burden on Providers and Impact of Portal Messages

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

Multiple sclerosis (MS) indirect patient-care time is often underreported and uncompensated. Data on time spent on indirect and direct care by MS providers is lacking.

METHODS:

A survey was designed to understand the practice patterns among MS providers in the United States, including time spent on direct and indirect patient care, as well as managing electronic medical record portal messages. The National MS Society and the American Academy of Neurology facilitated the distribution of the survey to MS providers.

RESULTS:

Most providers spent at least 1 hour on new and at least 30 minutes on follow-up direct patient care. For indirect patient care, 77% of providers spent more than 1 hour and 57% spent more than 2 hours per day. While some providers have support staff to help with portal messages, many do not have protected time or compensation for portal messages.

CONCLUSIONS:

Multiple sclerosis providers spent a higher-than-average time on direct and indirect patient care tasks, including portal messages, and most lack protected time or compensation for portal messages. These results highlight the potential impact of indirect patient care (notably portal messages) on provider workload and burnout. Better support, protected time and/or compensation for indirect patient care can help ease physician burden and decrease burnout.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic demyelinating disease of the central nervous system and a leading cause of disability among young adults.1 The prevalence of MS has increased in recent years with nearly 1 million people in the United States currently living with MS.2 At the same time, the US continues to face a shortage of neurologists3 and the complexity of MS management continues to increase due to more disease modifying treatment options (some with complex risk profiles)4 and the higher psychosocial and economic burden of the disease.5

Office visits with individuals with MS are already multifaceted and often last longer than the average neurological office visit.6,7 Also, providers are now spending more time with the electronic medical record (EMR) during and after the visit to document the encounter, place orders, and review results.8 In recent years, patient portal messages facilitated by the EMR have improved timely communications between patient and provider and have increased patient access to providers and medical records.9-11 These messages, however, are yet another provider care task and they do increase their workload.8,12,13 The recent COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated patient signup for EMR portals and increased the volume of portal messages.14

Neurology is one of the few specialties with a high rate of burnout and a low work-life balance satisfaction rate.15-17 A 2016 survey study showed that excessive workload, including long hours, high patient volumes, clerical burden, and inadequate support staff, were the major drivers of dissatisfaction among neurologists in the United States.17 We wanted to understand how recent changes in health care delivery, including portal messages and use, impact the workload and burden of MS care providers as a subset of neurology. Identifying and then addressing problem areas could help reduce provider burnout.

METHODS

An 8-question anonymous survey was developed via SurveyMonkey (TABLE S1, available online at IJMSC.org). A link to the survey was distributed via the National MS Society and American Academy of Neurology MS, Autoimmune, and General Neurology Synapse communities. The survey was live between June 2021 and September 2021 and a reminder email was sent out 1 month after the initial email.

The target population for the survey was MS providers including physicians, midlevel practitioners, and rehabilitation professionals. They were asked to disclose their current profession, type of practice, availability of support staff, time dedicated to MS care, time spent with new and follow-up patients, time spent in direct (ie, patient-facing) and indirect patient care, and whether time spent on portal messages was compensated. The indirect patient care question asked about time spent behind the scenes reviewing MRI scans and other test results, making phone calls to communicate results, maintaining documentation, teaching trainees, managing office staff, keeping up with license requirements, and prior authorization processing, in addition to monitoring portal messages. The survey also left space for additional comments at the end. Standard descriptive statistics were used to characterize responses. The study protocol and survey were reviewed and granted exempt status by the institutional review board of Saint Luke’s Marion Bloch Neuroscience Institute.

RESULTS

Respondent Demographics

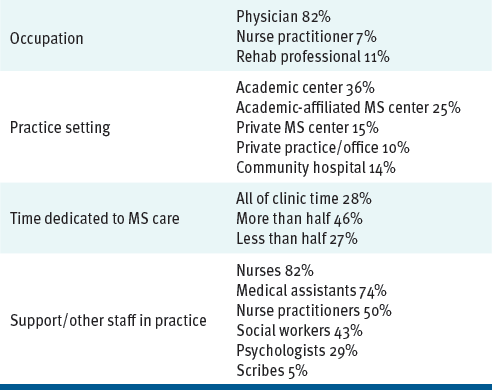

One hundred six participants completed the survey (TABLE 1). Respondents comprised physicians (82%); nurse practitioners (7%); and physical, occupational, or speech therapists (11%). The majority of respondents practiced in an academic center (36%) or an academic-affiliated MS center (25%). Of the respondents, 15% practiced in a private MS center, 10% in a private practice/office, and 14% in a community hospital.

Participant Demographics

Distribution of Effort/Time

Of the respondents, 28% indicated that all (100%) of their clinic time is dedicated to MS care; 46% disclosed that more than half of their clinic time is dedicated to MS care and 27% said that less than half of their time is dedicated to MS care.

The majority of respondents reported the availability of medical support staff, including nurses (82%), medical assistants (74%) and nurse practitioners (50%). Less common was support in the psychosocial areas, including social workers (43%) and psychologists (29%). Only 5% of respondents had access to scribes.

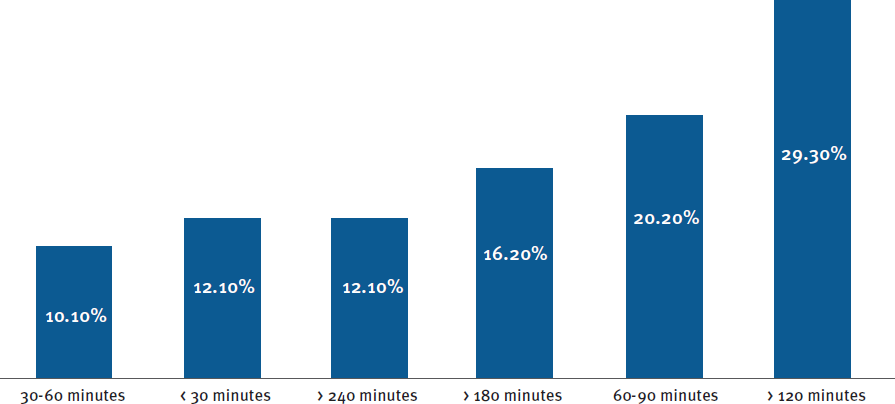

Sixty-four percent of respondents reported spending 1 hour with new patients, 25% reported spending 1 hour and 30 minutes, 8% reported spending 45 minutes or less, and 3% reported spending 2 or more hours (FIGURE S1A). Thirty-eight percent of respondents reported spending 30 to 40 minutes with follow-up patients, 29% reported spending 25 to 30 minutes, 22% reported spending 40 to 50 minutes, 7% reported spending 1 hour or more, and 4% reported spending 15 to 20 minutes (FIGURE S1B). Daily time spent in indirect patient care tended to be long for most providers: 77% spent more than 1 hour and 57% spent more than 2 hours per day on indirect patient care (FIGURE 1).

Time on Indirect Patient Care

Most respondents (76%) reported that they are not compensated for and do not have protected time to respond to portal messages. Although 31% had dedicated staff to respond to messages, only 6% reported protected time to respond and only 5% reported that they are compensated for time spent on portal messages (TABLE S2).

Generous entries in the comment section allow for a more detailed picture of practice patterns. Almost all provider comments highlighted that time spent in direct patient care often goes over time allotted by the practice or hospital system (eg, spending 1.5 hours for a new patient when the time allotted is 1 hour). Providers frequently spent up to 30 minutes reviewing records prior to new patient visits. Providers at academic centers often see patients with trainees (ie, fellows, residents, or students), which requires more time. The availability of clinic support staff streamlined the office visits. Even for providers with support staff who are available for portal messages, many felt that physician involvement or oversight was still required. Some comments mentioned a pervasive feeling of physician burnout. Paperwork, forms, and insurance approvals were mentioned in several comments as major components of indirect patient care and some respondents felt they contributed to provider burnout.

DISCUSSION

This survey of a representative sample of MS providers showed that they frequently spent greater-than-average time in direct and indirect patient care for new and follow-up patients and that most did not have adequate support for indirect patient care tasks, particularly for responding to portal messages. A growing tool for provider/patient communication,9,11,14,18 these messages are becoming a major part of indirect care11 with very little protected time or compensation for responding; this is expected to continue with the general adoption of EMR and uptick in patient portal use18 in differential primary and specialty medical settings.9-12,19 Most providers spent at least 1 hour per day on indirect patient care, despite the presence of support staff. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated portal use for results (eg, patients needing to know their COVID-19 test result) and telemedicine visits.14,18 Studies have shown that patient portal use is associated with improvement in patient-centered communication, patient engagement, adherence to a medication regimen, and discovery of medical errors10,12,20-22; however, patients and providers still face challenges with portal use and implementation, including a lack of engagement, a lack of integration into work routine, and limited time available for portal tasks.10,11 A recent study showed that portal use is common among people with MS and may be associated with disease complexity,23 but interestingly, another study showed no clear impact of portal use on frequency of office visits and hospitalizations among neurology patients.19 Our respondents acknowledged all of these complex issues.

While the relationship between portal messages and physician burnout has not yet been explored, portal messages are an extension of EMR use and recent research has explored its effect on physician burnout.8,13,24-26 Physician burnout is a response to excessive stress at work and is characterized by feeling emotionally drained and exhausted, experiencing depersonalization with lack of empathy, and a feeling of low personal accomplishments.27 Burnout contributes to poor patient care15 and is a common problem among many medical specialties.28

The impact of burnout in neurology has been well studied and was shown to be common in all neurology practice settings and subspecialities.15-17 Many factors contribute to physician burnout including, perhaps most importantly, lack of physician engagement.25,26 Other factors include excessive workload, EMR use, inefficient work processes, clerical burdens, work-home conflicts, and lack of physician input or autonomy on these issues.25,26 Neurology is a medical specialty with one of the lowest rates of satisfaction with EMR15 and time spent on EMR during and after patient visits, as well as after work hours, is a major contributor to physician burnout.8,24,25 In a complex disease like MS, EMR and portal use is likely to be high to address ongoing symptom management, disease modifying treatment discussions, and risk mitigation. Our respondents reported many hours of portal use per day and a significantly high number of hours per day spent on indirect patient care, which likely includes EMR use.

Reducing provider burden is critically important given the predicted neurologist shortage. In 2013, Dall et al estimated that the demand for neurologists will significantly exceed the supply by 2025.3 MS provider shortages are projected to increase over the next 2 decades, which may negatively impact the quality of care for this patient population.29

This study has several limitations. Although it is a representative sample of different providers and different practice settings, we recognize that the sample size is relatively small. It is also possible that providers who face larger practice hurdles are more likely to respond to surveys such as this one. Thus, their responses may be less representative of the larger pool of neurologists. Prior work in burnout has demonstrated that this is a widespread issue that affects all ranks of neurology.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates that most MS specialists in the US spend more than the standard time with patients in clinic. Despite the variability in the availability of support staff (eg, nurses, medical assistants), most MS specialists spent at least 1 hour daily responding to portal messages and most were not compensated for this effort.

We hope that our work will motivate larger and more in-depth studies into the impact of indirect patient care and portal use on MS providers. We believe that this knowledge can inform policy makers and societies and that time spent in indirect patient care can be better supported by institutions and practices. Some health care systems have recently started billing insurance for certain types of portal messages,30 which may be a proactive step toward addressing the issues raised in this study.

PRACTICE POINTS

Multiple sclerosis care providers spend a higher-than-average time in direct and indirect patient care.

While portal messages improve patient-centered care and patient-provider communication, they are adding to indirect patient-care time and increasing burnout.

Strategies to mitigate provider burden, such as hiring and training support staff, being compensated for portal messages, or protecting clinicians’ time, can reduce physician burnout.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

The authors thank the Saint Luke’s Foundation and the Saint Luke’s Marion Bloch Neuroscience Institute General Research Fund for supporting this project. The authors acknowledge the American Academy of Neurology and the National MS Society, specifically Suzanne Carron, for distributing and promoting the survey.

References

Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med . 2018;378 (2): 169-180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1401483

Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology . 2019;92 (10):e1029-e1040. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035

Dall TM, Storm MV, Chakrabarti R, et al. Supply and demand analysis of the current and future US neurology workforce. Neurology . 2013;81 (5): 470-478. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b1cf

Cross A, Riley C. Treatment of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) . 2022;28 (4): 1025-1051. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000001170

Bebo B, Cintina I, LaRocca N, et al. The economic burden of multiple sclerosis in the United States: estimate of direct and indirect costs. Neurology . 2022;98 (18):e1810-e1817. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200150

Brownlee WJ, Ciccarelli O. All relapsing multiple sclerosis patients should be managed at a specialist clinic - YES. Mult Scler . 2016;22 (7): 873-875. doi: 10.1177/1352458516636474

Roberts JI, Hahn C, Metz LM. Multiple sclerosis clinic utilization is associated with fewer emergency department visits. Can J Neurol Sci . 2022;49 (3): 393-397. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2021.118

Kroth PJ, Morioka-Douglas N, Veres S, et al. Association of electronic health record design and use factors with clinician stress and burnout. JAMA Netw Open . 2019;2 (8):e199609. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9609

Beal LL, Kolman JM, Jones SL, Khleif A, Menser T. Quantifying patient portal use: systematic review of utilization metrics. J Med Internet Res . 2021;23 (2):e23493. doi: 10.2196/23493

Stewart MT, Hogan TP, Nicklas J, et al. The promise of patient portals for individuals living with chronic illness: qualitative study identifying pathways of patient engagement. J Med Internet Res . 2020;22 (7):e17744. doi: 10.2196/17744

Zaidi M, Amante DJ, Anderson E, et al. Association between patient portal use and perceived patient-centered communication among adults with cancer: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res (Cancer) . 2022;8 (3):e34745. doi: 10.2196/34745

Sun R, Korytkowski MT, Sereika S, Saul MI, Li D, Burke LE. Patient portal use in diabetes management: literature review. J Med Internet Res (Diabetes) . 2018;3 (4):e11199. doi: 10.2196/11199

Tajirian T, Stergiopoulos V, Strudwick G, et al. The influence of electronic health record use on physician burnout: cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res . 2020;22 (7):e19274. doi: 10.2196/19274

Grossman SN, Han SC, Balcer LJ, et al. Rapid implementation of virtual neurology in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology . 2020;94 (24): 1077-1087. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009677

Bernat JL, Busis, NA. Patients are harmed by physician burnout. Neurol Clin Pract . 2018;8 (4): 279-280. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000483

Busis NA. To revitalize neurology we need to address physician burnout. Neurology . 2014;83 (24): 2202-2203. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001087

Busis NA, Shanafelt TD, Keran CM, et al. Burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being among US neurologists in 2016. Neurology . 2017;88 (8): 797-808. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003640

Lo B, Charow R, Laberge S, Bakas V, Williams L, Wiljer D, et al. Why are patient portals important in the age of COVID-19? Reflecting on patient and team experiences from a Toronto hospital network. J Patient Exp . 2022, 9:23743735221112216. doi: 10.1177/23743735221112216

Ochoa C, Baron-Lee J, Popescu C, Busl KM, et al. Electronic patient portal utilization by neurology patients and association with outcomes. Health Informatics J . 2020;26 (4): 2751-2761. doi: 10.1177/1460458220938533

Antonio MG, Petrovskaya O, Lau F. The state of evidence in patient portals: umbrella review. J Med Internet Res . 2020;22 (11):e23851. doi: 10.2196/23851

Dendere R, Slade C, Burton-Jones A, Sullivan C, Staib A, Janda M. Patient portals facilitating engagement with inpatient electronic medical records: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res . 2019;21 (4):e12779. doi: 10.2196/12779

Kruse CS, Argueta DA, Lopez L, Nair A. Patient and provider attitudes toward the use of patient portals for the management of chronic disease: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res . 2015;17 (2):e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3703.

Khalil N, Aungst A, Casady L, et al. Multiple sclerosis and MyChart messaging: a retrospective chart review evaluating its use. Int J MS Care . 2022;24 (6): 271–274. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2020-101

Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Family Med . 2017;15 (5): 419-426. doi: 10.1370/afm.2121

Gardner RL, Cooper E, Haskell J, et al. Physician stress and burnout: the impact of health information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc . 2019;26 (2): 106-114. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy145

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt, TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med . 2018;283 (6): 516-529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav . 1981;2 (2): 99-113. doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

Rao S, Ferris TG, Hidrue MK, et al. Physician burnout, engagement and career satisfaction in a large academic medical practice. Clin Med Res . 2020;18 (1): 3-10. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2019.1516

Halpern MT, Kane H, Teixeira-Poit S, et al. Projecting the adequacy of the multiple sclerosis neurologist workforce. Int J MS Care . 2018;20 (1): 35-43. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2016-044

Cleveland Clinic: MyChart messaging. Accessed Nov 20, 2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/online-services/mychart/messaging

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: Dr Mahmoud was on the speaker’s bureau for Biogen and has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Horizon Therapeutics, and Sanofi Genzyme. Dr Chahin receives research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb and the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation and consulting fees from Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Horizon Therapeutics, Jansen, Novartis, and Sanofi Genzyme.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Saint Luke’s Foundation and the Saint Luke’s Marion Bloch Neuroscience Institute General Research Fund.

PRIOR PRESENTATIONS: Preliminary data from this manuscript were presented as a poster at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) Forum; February 2022; West Palm Beach, Florida; and at the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) Annual Meeting; June 2022; Washington, DC.