Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Development and Effectiveness of a Psychoeducational Wellness Program for People with Multiple Sclerosis

Background: Multiple sclerosis (MS) mostly affects young and middle-aged adults and is known to be associated with a host of factors involved in overall quality of life and well-being. The biopsychosocial model of disease takes into account the multifaceted nature of chronic illness and is commonly applied to MS. The present investigation examined the effectiveness of a 10-week psychoeducational MS wellness program that was developed on the basis of the biopsychosocial model and a wellness approach to treatment.

Methods: The program consisted of 90-minute, weekly psychoeducational wellness group sessions aimed at improving quality of life by increasing awareness of the various social, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual factors that can affect the overall well-being of people living with MS. Fifty-four individuals with MS participated in the study (43 individuals who completed the wellness intervention and 11 individuals with MS who did not participate; “controls”). All participants completed a series of self-report questionnaires at baseline and at the 10-week follow-up, assessing depression, anxiety, perceived stress, cognitive complaints, pain, social support, and fatigue.

Results: Repeated-measures analysis revealed improvements in depression, anxiety, overall mental health, perceived stress, and pain in the treatment group compared with the control group. No significant differences were observed between the groups on measures assessing social support, cognitive complaints, and fatigue.

Conclusions: The findings suggest that a psychoeducational wellness program is effective in improving the overall quality of life and well-being of individuals with MS.

Approximately 400,000 people have been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) in the United States. Although the course of MS is unpredictable and there is still no known cure, disease-modifying treatments and a rehabilitation approach have been the primary means of delaying progression of MS symptoms and reducing exacerbations.1 While the physical symptoms of the disease have a significant impact on the lives of individuals with MS, many other disease-related factors (eg, depression, fatigue, cognitive difficulties) also pose grave challenges.2–8 People with MS must cope with an unpredictable and variable neurodegenerative disease and frequently report feeling overwhelmed by the multidimensional nature of the illness.9 10 Psychological and social adaptation to this process can be optimized with adequate resources, support, and education. Therefore, an outpatient wellness program may address the specific biopsychosocial needs of individuals living with MS. The pilot study reported here examined whether a wellness program could improve psychosocial functioning in people with MS.

The development of a psychoeducational support group series for individuals living with MS was inspired by clinical research indicating that factors such as active coping, social support, and benefit finding improve self-reported quality of life (QOL). The specific aims of the program were to address common underlying factors related to poor QOL in MS—namely, depression, anxiety, fatigue, cognitive complaints, stress, and limited social support—and to teach coping strategies to help reduce negative symptoms and increase daily QOL.

The decision to offer a wellness program based on a group therapy model was largely predicated on the concept that group therapy can reduce feelings of alienation and encourage expression of emotions related to the disease, as well as providing peer support.9 Additionally, because of the interactional nature of physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms in MS, an individual can minimize or misinterpret cognitive and emotional sequelae of MS. In a group setting, people can provide feedback to one another, which often highlights discrepancies between self-perceived deficits and the impressions of peers.

A wellness program has the advantages of addressing multiple factors affecting everyday life in an integrated and interactive fashion. Decades of research have shown that emotional distress (eg, depression and anxiety) is very common in people with MS and significantly affects everyday functioning.2–4 Similarly, it is well known that fatigue not only is a frequent symptom of MS, occurring in approximately 90% of people with the disease,5 but has often been described as the most disabling symptom.6 7 An estimated 43% to 70% of individuals with MS experience cognitive difficulties,8 which often lead to significant decrements in overall level of functioning and QOL (eg, unemployment). Moreover, cognitive changes can affect an individual's self-esteem and self-identity and lead to decreased social engagement.11 It has also been shown that one's perceived cognitive difficulties can have a serious negative impact on the individual and his or her overall functioning. Additionally, research suggests a link between stress and exacerbations in MS.12 13 Depression, negative attributions, poor coping skills, and low levels of social support have all been implicated as factors that aggravate the relationship between stress and exacerbations.14 Effective stress management interventions have been proposed for use in MS. Lastly, several decades of clinical research have shown that perceived social support affects QOL for people with MS.15–17

The “Living With Multiple Sclerosis Support Group Series” is a wellness program designed to address the above-mentioned QOL components—depression, anxiety, fatigue, perceived cognitive complaints, stress, and social support—through a group format consisting of a didactic component, an interactive component, and a group processing component. The overall aim of the psychoeducational support group is to improve QOL by increasing awareness of the various social, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual factors that can affect one's overall well-being when living with MS and discussing effective coping strategies.

To date, few controlled studies have been conducted evaluating the effectiveness of a wellness approach. Stuifbergen et al.18 examined a wellness approach for women living with MS that focused on health behaviors and QOL. They found that women who participated in an 8-week wellness program consisting of lifestyle-changing classes and homework assignments exhibited improvement in mental health, pain, and self-efficacy for health behaviors, indicating the effectiveness of the wellness approach. The present study adopted a similar approach, but included both genders in the program, which was 10 weeks long and focused more on psychoeducation related to the multifaceted impact of MS on QOL. It was thought that this would provide program participants with tools with which to develop better coping mechanisms.

Other wellness programs were also found to be effective in improving mental health and overall well-being of individuals with MS; however, because of the lack of a control group in these studies, it is difficult to attribute observed changes to treatment. For example, a study by Hart et al.19 of participants in a wellness program found improvements in depression, functional status, and fatigue. Another study by Ng et al.20 highlighted the positive impact of a wellness program on self-efficacy and health status; again, however, there was no control group. Tesar et al.21 examined the effectiveness of psychological interventions (although not in a formal wellness group), such as cognitive-behavioral strategies and stress-coping training, and found that depressive stress-coping style improved in the experimental group compared with the control group. Finally, one previous study22 used a theory-driven approach to improve coping skills in an MS sample. Individuals in the coping skills intervention group were compared with those in a telephone-based peer support group. Individuals in the coping skills group achieved gains in various aspects of QOL (eg, internal locus of control, social activity, family satisfaction, and global satisfaction), which was not evident in the telephone-based peer support group.

The MS wellness program described in the present article is an extension of the well-thought-out approach of Schwartz22; however, it focuses on empowerment through a psychoeducational approach, combining a didactic component (ie, presentation of evidence-based practices and interventions), a therapeutic component (ie, group therapy process), and an interactive component (ie, discussion and/or activity that highlights implementation of the information disseminated). As the nature of health care has drastically shifted over the past decade, it has become even more important for people with MS to learn self-empowerment through self-advocacy regarding the care they receive, which is consistently emphasized throughout the MS wellness program.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the effectiveness of the wellness program by comparing those who completed the intervention with those in a control group. Because the program was implemented as regular clinical care, and individuals who participated in the program were not randomly selected, the present study cannot be considered a randomized controlled clinical trial; rather, it is an initial pilot study. We hypothesized that participants in the treatment group (ie, psychoeducational support group series) would demonstrate improvements in anxiety, depression, fatigue, perceived cognitive complaints, and stress relative to individuals in the control group.

Methods

Participants

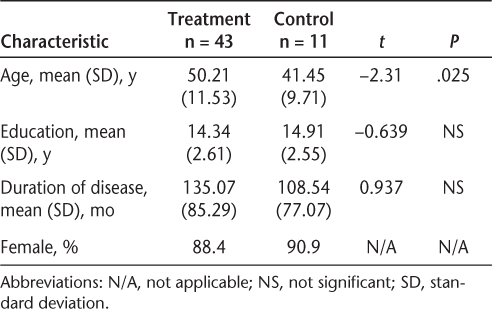

Seventy-two participants completed the study, of which 61 were in the treatment group and 11 in the control group. All participants had a clinically definite MS diagnosis per McDonald criteria.23 All participants were able to speak, read, and write in English. Seventeen treatment group participants were lost to follow-up, and one treatment group participant was excluded from analysis because of missing data both at baseline and at follow-up. People in the treatment group had participated in the wellness program over the course of several years. The control group consisted of a convenience sample recruited from the Kessler Foundation database over the course of several months until a sufficient sample size was achieved. Demographic information for participants in the treatment and control groups is shown in Table 1.

Participant demographics

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the Kessler Foundation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants either at the onset of the program or at their baseline evaluations, if controls. Participants completed a series of questionnaires at the beginning of the program and at the 10-week follow-up. Individuals in the treatment group attended a clinical psychoeducational wellness program consisting of weekly 90-minute group sessions over 10 consecutive weeks, focusing on enhancing coping strategies for various aspects of MS. The wellness program took into account the biopsychosocial model, which included impact of daily life pressures, social support, vocational responsibilities, communication with others, physical symptoms, and mood symptoms. Additionally, the program used a wellness approach, which puts emphasis on personal responsibility, complements and supports medical treatment, and teaches individuals how to develop lifestyle strategies to enhance QOL. The psychoeducational wellness sessions consisted of a 30-minute educational segment, followed by a 60-minute interactive and group process component.

Individuals in the treatment group were referred from various sources to the rehabilitation hospital, including a posting on the New Jersey Metro Chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society website, weekly e-mails to MS Society members, a monthly newsletter distributed by the New Jersey MS Society chapter, and informational flyers that were provided to neurologists and outpatient physical rehabilitation facilities. Interested individuals contacted the office manager at the Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation and scheduled an appointment for a clinical diagnostic interview. Control group participants were identified from the internal database containing the names and phone numbers of individuals with MS.

Participants completed a total of eight questionnaires, six of which were part of the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory,24 at baseline and follow-up. A short description of each questionnaire is provided below.

Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Questionnaire

The Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Questionnaire (MSNQ)25 is a 15-item questionnaire assessing self-reported neuropsychological impairment in processing speed and memory. It is measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, with a total score ranging from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate greater self-reported impairment of processing speed and memory.

Perceived Deficits Questionnaire 5-Item Version

The Perceived Deficits Questionnaire (PDQ) 5-item version is a shorter version of the 20-item PDQ, which evaluates subjective self-report of cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and executive function. Patients rate themselves on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, with the total score ranging from 0 to 20. Higher scores indicate greater self-reported cognitive impairment.

Beck Depression Inventory–Fast Screen

The Beck Depression Inventory–Fast Screen (BDI-FS)26 was created for use within a medical sample. It consists of only seven items thought to be nonconfounded by medical illness (sadness, pessimism, past failure, loss of pleasure, self-dislike, self-criticalness, and suicidal ideation). Patients rate themselves on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3 for the extent to which they have experienced the symptom in the past 2 weeks, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 21.

Modified Fatigue Impact Scale 5-Item Version

The Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) 5-item version was developed from the 21-item MFIS in order to shorten the time of the questionnaire administration. It consists of five items assessing fatigue in individuals with MS and discriminating between fatigue reported by MS patients and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome or essential hypertension. Patients rate themselves on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, with the total score ranging from 0 to 20. Higher scores indicate greater levels of fatigue.

Medical Outcomes Study Pain Effects Scale

The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Pain Effects Scale (PES) is a 6-item scale that assesses how pain and other unpleasant sensations affect mood, movement, recreation, and overall QOL. Patients rate themselves on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, with the total score ranging from 6 to 30. Higher scores indicate a larger effect of pain on QOL.

Mental Health Inventory

The Mental Health Inventory (MHI) is an 18-item scale designed to assess mental health status in terms of levels of anxiety, depression, behavioral and emotional control, and positive affect. The MHI yields a total MHI score as well as scores for the following subscales: MHI Anxiety, MHI Depression, MHI Behavioral and Emotional Control, and MHI Positive Affect (PA). Patients are asked to rate themselves on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 6, with the total score ranging from 0 to 100 after the score conversions for specific items. Higher scores indicate better mental health.

MOS Modified Social Support Survey

The MOS Modified Social Support Survey (MSSS) is an 18-item scale assessing various aspects of perceived social support. In addition to the total MSSS score, the measure consists of the following subscales: tangible support, emotional support, affective support, and positive support. Patients are asked to rate themselves on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, with the total score ranging from 0 to 100 after the score conversions for specific items. Higher scores indicate better perceived social support.

Perceived Stress Scale

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)27 is a 10-item questionnaire measuring the degree of perceived stress as viewed through the feelings and thoughts of an individual over the past month. Patients rate themselves on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, with the total score ranging from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of perceived stress. The PSS was administered only to a subgroup of 10 treatment group participants and the control group, as it was proposed for inclusion at a later date. There were no significant demographic differences in age and education between these 10 and the other 33 treatment group participants.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0. Independent-samples t tests were conducted to compare group means for age, education, and duration of disease. Repeated-measures analyses were performed to evaluate differences between the groups on each of the constructs from baseline to the 10-week follow-up, as measured by the questionnaires.

Results

Independent-samples t tests showed that control group participants were significantly younger than treatment group participants (t = −2.312, P = .025). There were no differences between groups with regard to amount of education and duration of disease. Therefore, age was entered as a covariate in all subsequent analyses.

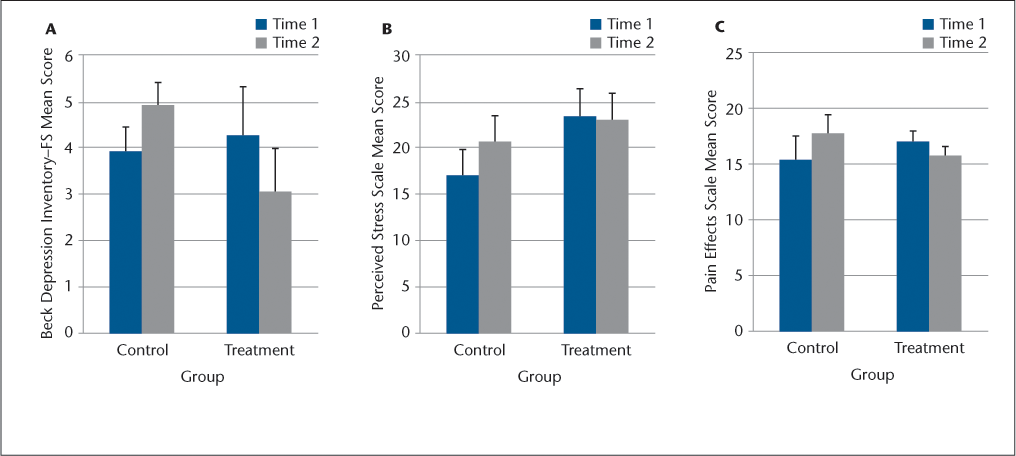

A repeated-measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) revealed a significant group effect over time indicating improvement in the treatment group and a decline in the control group for depression, anxiety, pain, and perceived stress. For depression, there was a significant reduction in scores in the treatment group as compared with the control group from baseline to follow-up on the BDI-FS (F 1,47 = 4.12, P = .048). A significant decrease in scores from baseline to follow-up in the treatment group as compared with the control group was also noted for perceived stress (PSS) (F 1,19 = 5.25, P = .033) and pain (PES) (F 1,51 = 5.11, P = .028) (Figure 1). Higher scores on the BDI-FS, PSS, and PES indicate worse self-reported mental health, including depression, pain effects, and perceived stress.

Group differences as a factor of time

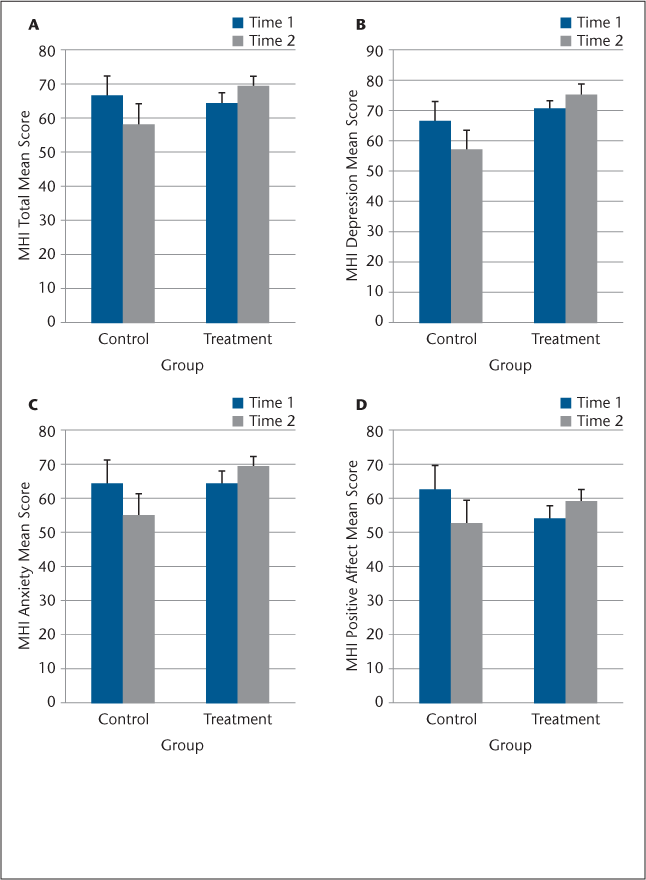

In terms of overall mental health, for the MHI Total, Depression, Anxiety, and PA subscales, the individuals in the treatment group had a significant increase in scores from baseline to follow-up relative to controls (Figure 2): MHI Total (F 1,50 = 9.67, P = .003), MHI Depression subscale (F 1,50 = 5.12, P = .028), MHI Anxiety subscale (F 1,50 = 5.87, P = .019), and MHI PA subscale (F 1,50 = 7.31, P = .009). For the MHI and the subscales of the MHI, higher scores indicate better self-reported mental health. Thus, the results indicate improvement in self-reported mental health for the treatment group compared with the control group, for which the results showed a decline in self-reported mental health.

Mental Health Inventory (MHI) group differences as a factor of time

Upon closer inspection of the prevalence of depression in the two groups, we found that, at baseline, 54% of the study sample met criteria for depression according to the BDI-FS cutoff score of 4 or higher for depression in MS,28 with 46% of individuals from the control group and 56% from the treatment group meeting criteria for depression. These rates were not significantly different between the two groups (χ2 = 0.415, P = .520). At the 10-week follow-up, the rate of depression for the study sample was 46%, with 64% of the control group sample meeting criteria for depression, compared with 41% in the treatment group. A total of 22 individuals from the treatment group met criteria for depression on the BDI-FS prior to the commencement of the wellness program, while only 12 of the 22 still met the criteria at follow-up, indicating a reduction of depression in approximately half of the treatment group (45.5%).

The observation that self-reported pain was reduced following the intervention raised the question of whether these perceptions of pain were related to depression and anxiety, as these also were reduced following treatment. Therefore, we examined the relationship among pain, depression, and anxiety. There was a significant correlation between pain and depression both at baseline (r = 0.322, P = .022) and at the 10-week follow-up (r = 0.414, P = .003), as well as between pain and anxiety at baseline (r = −0.325, P = .018) and at 10-week follow-up (r = −0.529, P = .001).

Discussion

The development of the psychoeducational support group series based on a biopsychosocial model and wellness approach was designed to improve QOL among individuals with MS. A comprehensive, whole-person approach to MS care has been recommended. To date, such an approach has yielded positive findings (eg, Hart et al.19). However, some of these findings have been limited in their interpretation and applicability given the lack of a control group. The present investigation utilized a no-treatment control group in the analysis of the effectiveness of a wellness program for individuals of both genders who are living with MS.

The results of the present study showed that, relative to controls, the treatment was effective in improving self-reported depression, anxiety, perceived stress, and pain. The findings also suggest that participants in the treatment group experienced an increase in positive affect. No changes were observed in self-reported cognitive complaints, social support, or fatigue.

Reductions in depression following a group-based intervention are consistent with previous study findings.19 29 While within-group rate of change in depression was not significant, nearly one-half (45.5%) of the treatment group sample no longer met criteria for depression at the 10-week follow-up. With regard to the observed reduction in self-reported pain, positive correlations between pain, depression, and anxiety suggest that the coping strategies introduced through treatment over the course of 10 weeks may have helped reduce depression and anxiety, resulting in an indirect decrease in pain in the treatment group. Finally, regarding perceived stress, although individual group effects were not found, the interactions between time and group revealed that those in the control group demonstrated an increase in perceived stress while those in the treatment group did not. This increase in perceived stress among the controls suggests that the control group participants' concern about potential stressors may have increased by virtue of completing self-report questionnaires highlighting important QOL factors, without having access to effective coping strategies to reduce the negative impact of those stressors. It is plausible that participants in the treatment group improved their coping strategies, reducing the negative impact of stress on overall well-being. Additionally, a reduction in stress may result in reductions in depression and anxiety, in turn resulting in reduced perceptions of pain. Finally, the findings of increased stress only in the control group may result from history effects due to the control group individuals being seen at different time periods than the treatment group participants, with different seasonal events over the 10-week period.

The hypothesis that people receiving the wellness intervention would experience a decrease in self-reported fatigue was not supported in the present study; this may be due largely to the complex nature of fatigue. Previous studies have shown that pharmacologic interventions and aerobic exercise,30–33 as well as cognitive-behavioral therapy,34 can reduce fatigue in MS. These interventions were not part of the psychoeducational wellness program described in this study.

The complex nature of MS requires a multidimensional approach to treatment. An important factor in treatment is empowering the person living with the disease. The “Living With Multiple Sclerosis Support Group Series” provided a supportive and comprehensive learning environment focused on teaching participants how to effectively manage the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual components of QOL. This psychoeducational wellness program promoted the concept of self-advocacy by improving self-efficacy, coping skills, and access to a support system. Treatment group participants showed improvements in levels of depression, anxiety, perceived stress, and pain that were not evident in the control group.

The group therapy model was important to the success of the wellness program for people with MS, providing a forum for discussion of successes and challenges in the implementation of newly learned coping strategies and skills. Previous studies examining a variety of psychotherapeutic approaches in a group setting to increase the QOL of individuals with MS have found improvements primarily in depression (see Firth29 for a review). The lack of a control group in these studies, however, makes it difficult to determine the actual effectiveness of the intervention versus change over time alone.

While this study shows promising results, certain limitations temper the findings. First, the control group sample size was small. A sample of comparable size to the treatment group, possibly even a matched sample, would be ideal. Further limitations arise from the possible history effects, as the two groups were not completing the questionnaires at the same time, making the results susceptible to seasonal differences in stressors. Finally, as this pilot study was not a randomized controlled trial, the control group did not have a “placebo” intervention throughout the course of 10 weeks that would equate the amount of “attention” given the two groups, raising the question of whether participation in the treatment group alone can account for the results. Despite these limitations, the significant preliminary findings of this study can inform future exploration of the effectiveness of psychoeducational wellness programs for people with MS. Clearly, a larger randomized clinical trial is warranted. Additionally, future studies should incorporate a longer (eg, 3-month) follow-up period to assess the sustainability of the positive results.

PracticePoints

The biopsychosocial model of disease takes into account the multifaceted nature of chronic illness and is often applied in the field of MS.

The complex nature of MS requires a multidimensional approach to treatment.

A psychoeducational wellness program is an effective supplement to traditional medical management to improve the overall quality of life and well-being of individuals with MS.

The aim of a wellness program is to provide a supportive learning environment focused on teaching people with MS how to manage disease-related challenges in the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains that affect their quality of life.

References

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Rehabilitation: Recommendations for Persons with Multiple Sclerosis 2007. www.nationalmssociety.org. Accessed January 2, 2007.

Benito-Leon J, Morales JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Health-related quality of life and its relationship to cognitive and emotional functioning in multiple sclerosis patients. Eur J Neurol. 2009; 9: 497–502.

Kern S, Schrempf W, Schneider K, Schulteiss T, Reichmann R, Ziemssen T. Neurological disability, psychological distress, and health-related quality of life in MS patients within the first three years after diagnosis. Mult Scler. 2009; 15: 752–758.

Chwastiak L, Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, Sullivan M, Bowen JD, Kraft GH. Depressive symptoms and severity of illness in multiple sclerosis: epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159: 1862–1868.

Schapiro R. The pathophysiology of MS-related fatigue: what is the role of wake promotion? Int J MS Care. 2002;(suppl):6–8.

Krupp LB, Christodoulou C, Schombert H. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue. In: DeLuca J, ed. Fatigue as a Window to the Brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005:61–71.

Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinber LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988; 45: 435–437.

Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008; 7: 1139–1151.

Kalb R. Emotional and social impact of cognitive changes. In: LaRocca N, Kalb R, eds. Multiple Sclerosis: Understanding Cognitive Challenges. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2006:3–16.

Kalb R, Miller D. Psychosocial issues. In: Kalb R, ed. Multiple Sclerosis: The Questions You Have, the Answers You Need. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2004:233–271.

Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, Galvin K, Baker R. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:(1):CD004431.

Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Islar J, Hauser SL, Genain CP. Treatment of depression is associated with suppression of nonspecific and antigen-specific T(H)1 responses in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2001; 58: 1081–1086.

Mohr DC, Genain D. Social support as a buffer in the relationship between treatments for depression and T-cell production of interferon gamma in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2004; 57: 155–158.

Mohr DC. Stress and multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254:II/65–68.

Crigger NJ. Testing an uncertainty model for women with multiple sclerosis. Adv Nurs Sci. 1996; 18: 37–47.

Wineman NM. Adaptation to multiple sclerosis: the role of social support, functional disability, and perceived uncertainty. Nurs Res. 1990; 39: 294–299.

McCabe M, McKern S, McDonald E. Coping and psychological adjustment among people with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2004; 56: 355–361.

Stuifbergen AK, Becker H, Blozis S, Timmerman G, Kullberg V. A randomized clinical trial of a wellness intervention for women with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003; 84: 467–476.

Hart DL, Memoli RI, Mason B, Werneke MW. Developing a wellness program for people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2011; 13: 154–162.

Ng A, Kennedy P, Hutchinson B, et al. Self-efficacy and health status improve after a wellness program in persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2013; 35: 1039–1044.

Tesar N, Baumhackl U, Kopp M, Guenther V. Effects of psychological group therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003; 107: 394–399.

Schwartz CE. Teaching coping skills enhances quality of life more than peer support: results of a randomized trial with multiple sclerosis patients. Health Psychol. 1999; 18: 211–220.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Annals Neurol. 2011; 69: 292–302.

Fisher J, LaRocca N, Miller D, Ritvo P, Andrews H, Paty D. Recent developments in the assessment of quality of life in multiple sclerosis (MS). Mult Scler. 1999; 4: 251–259.

Benedict RHB, Cox D, Thompson LL, Foley F, Weinstock-Guttman B, Munschauer F. Reliable screening for neuropsychological impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004; 10: 675–678.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory–Fast Screen. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, USA; 2000.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983; 24: 385–396.

Benedict RHB, Fishman I, McClellan MM, Bakshi R, Weinstock-Guttman B. Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory–Fast Screen in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 393–396.

Firth N. Effectiveness of psychologically focused group interventions for multiple sclerosis: a review of the experimental literature. J Health Psychol. 2013; 19: 789–801.

Jongen PJ, Lehnick D, Sanders E, et al. Health-related quality of life in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients during treatment with glatiramer acetate: a prospective, observational, international, multi-centre study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010; 8: 133–140.

Montalban X, Comi G, O'Connor P, et al. Oral fingolimod (FTY720) in relapsing multiple sclerosis: impact on health-related quality of life in a phase II study. Mult Scler J. 2011; 17: 1341–1350.

Pilluti LA, Greenlee TA, Motl RW, Nickrent MS, Petruzzello SJ. Effects of exercise training in fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2013; 75: 575–580.

Mostert S, Kesselring J. Effects of a short-term exercise training program on aerobic fitness, fatigue, health perception and activity level of subjects with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2002; 8: 161–168.

Mohr DC, Hart SL, Goldberg A. Effects of treatment for depression on fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65: 542–547.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. DeLuca has received grant funding from Biogen Idec and has served as a consultant to Biogen Idec, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and the National Hockey League and Major League Soccer. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This project was supported in part by a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (grant #MB 0024) to Dr. DeLuca.