Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Developing a Wellness Program for People with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Because multiple sclerosis (MS) is a multidimensional chronic disease, effective management of the illness requires a multidimensional approach. We describe a wellness program that was designed to facilitate positive health choices throughout the course of MS and present initial data analyses. We hypothesized that over the course of the program, participants would demonstrate improvement in the domains assessed. The wellness program included educational sessions in physical, mental, social, intellectual, and spiritual domains specifically targeting improved self-efficacy, physical functioning, coping skills, symptom management, and nutrition. An outcomes data collection software program was adapted to facilitate real-time patient self-report and clinician entry data collection for many domains throughout the wellness program. Initial assessment of serial measures (intake to discharge) from 65 people with MS showed improvement in several domains, including functional status (P < .05), fatigue (P < .05), fear-avoidance beliefs regarding physical activities (P < .05), depression (P < .05), somatization (P < .05), and pain (P < .05). In addition, using a model of risk for interpersonal distress, patients whose risk of elevated depression and anxiety decreased over the course of the program reported greater gains in functional status (P < .05). The results suggest possible future treatment strategies and indicate strengths and weaknesses of the wellness program, which are being used to improve the program.

Individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) often report the multidimensionality of the effects of this chronic disease, along with many ways of managing these varied symptoms.1 For example, people with MS and their clinicians may be concerned about an acute attack producing an irreversible deficit, which could influence clinical management.1 However, such incidents are rare, so some believe that concerns about irreversible disability should not influence therapeutic decisions,2 advocating instead an approach of “patience”1 and conservative management, particularly when dealing with common MS sequelae such as decreased functional status,2 decreased balance,3 increased depression,4 increased anxiety,5 and difficulty coping with and managing symptoms associated with MS.6 We operationally define conservative management as a set of clinical evaluation, education, and treatment techniques associated with outpatient rehabilitation, as contrasted with pharmacologic intervention or hospital admission. Such conservative management programs, if successful and cost-effective, could provide more options to people with MS. Designing a conservative intervention program that incorporates many of the domains affecting people with MS is challenging.

In developing a wellness program for people with MS, we concentrated on domains that affect people with MS, affect rehabilitation success, can be included easily in a wellness program, and can be quantified. For example, people with MS report decreased functional status.2 Efficient and precise methods of assessing patient-reported functional status have evolved, facilitating quantification in rehabilitation.7 People with MS also are affected by psychosocial factors that can play a role in the development of chronic disability. Therefore, we selected a scale, the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs of Physical Activity Questionnaire (FABQ),8 that quantifies a person's level of fear-avoidance beliefs regarding physical activities; when elevated, it has been associated with poor functional status outcome.9 The model on which the FABQ is based posits that an individual's response to an episode of pain falls along a continuum ranging from avoidance (maladaptive) to confrontation (adaptive) and provides one explanation of why a minority of patients with musculoskeletal pain syndromes may develop chronic disability. Although no published articles describe use of the FABQ to assess people with MS, we have found that the FABQ is answered in a similar and valid manner by patients with neurologic and those with orthopedic impairments receiving outpatient therapy, regardless of whether patients have pain.10

In addition, depression and somatization11 are recognized as common confounders of clinical outcomes,12 including in people with MS.4 The point prevalence of major depression may be as high as 17% in patients seen by primary-care providers, yet some believe the prevalence of depressive disorders in people with MS is much higher. The prevalence of somatization is difficult to assess, but it is common in people with MS.5 13 Likewise, fatigue is common in people with MS.14 Fatigue is a complex clinical phenomenon,15 in part because it is associated with depression,16 physical functioning, and self-efficacy.17 A rapid screening tool, the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS), was selected.15 18 Finally, although pain may not be as prevalent as fatigue, depression, somatization, and low functional abilities in people with MS, because pain can affect each of these constructs, we felt that the assessment of pain intensity was warranted.19

In order to facilitate efficient, simultaneous data collection involving several domains in real time, we explored advances in computerization for clinical practice. For example, functional status was assessed using a computerized adaptive testing (CAT) application7 because such applications allow precise estimates of functional status with reduced respondent burden. Reduced respondent burden facilitates data collection for other domains. In addition, use of modern psycho-metric methods, such as item response theory (IRT),20 provides ways of reducing the burden associated with classifying patients with elevated versus not elevated levels of fear-avoidance beliefs of physical activities.10 For domains that have not been assessed using IRT methods or estimated using CAT applications, data were collected using computer data entry and original surveys, with plans for analysis using IRT methods in the future. Finally, computerized outcomes data collection can be integrated into electronic health record systems, facilitating assessments of which treatments are associated with better outcomes for specific individuals.21

The overall purpose of this study was to describe development, implementation, and initial outcomes data results related to a multidimensional, conservative wellness program designed to facilitate positive health choices in people with MS. For initial outcomes data assessment, specific purposes were to determine whether, over the course of the wellness program, participants reported changes in functional status, fear-avoidance beliefs of physical activities, depression, somatization, fatigue, and pain intensity. We hypothesized that over the course of the program, participants would demonstrate improvement in the domains assessed. Initial analyses will be used to identify strengths and weaknesses of the wellness program in order to improve the program and accomplish program goals.

Methods

Participants and Setting

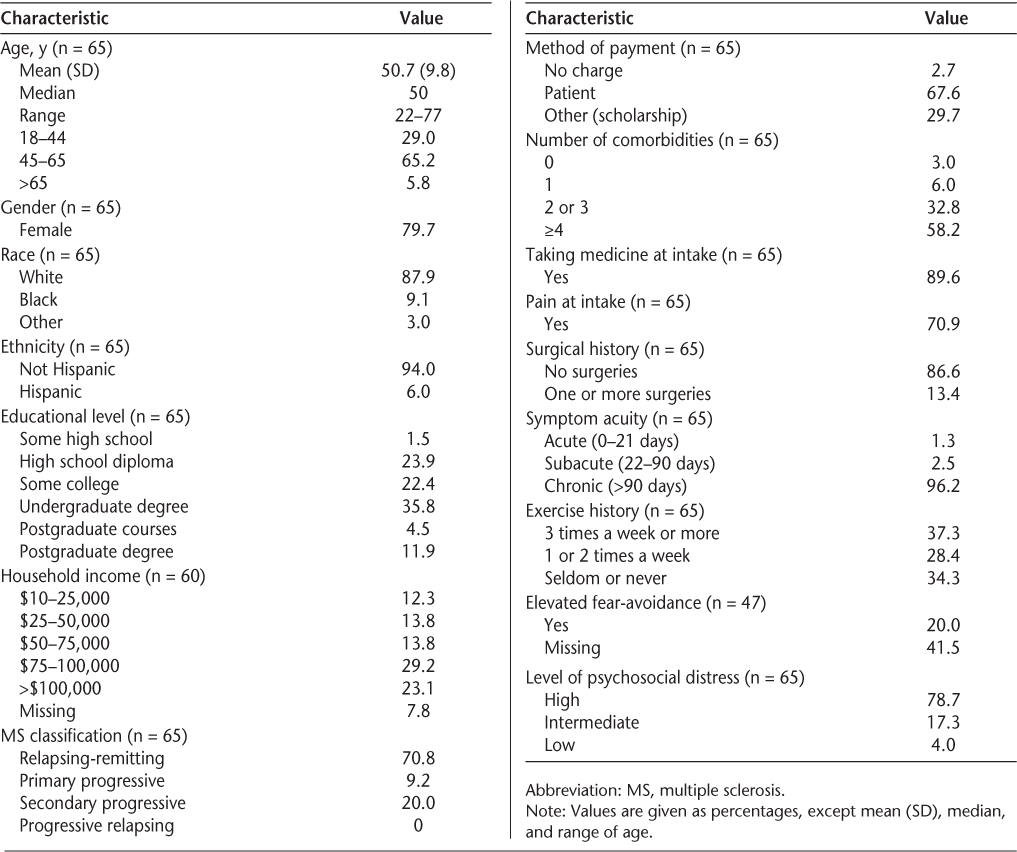

The participants in this study were 65 adult men and women with a mean age of 50.7 years (SD 9.8, median 50, range 22–77) (Table 1). These people were selected for analysis because they had participated in the wellness program and had entered data into the Focus On Therapeutic Outcomes, Inc (Knoxville, TN) outcomes computerized database, which CentraState Healthcare System (Freehold, NJ) used as their outcomes software. All had a diagnosis of MS, which was the only inclusion criterion. All participants either were referred to the program by their physician or referred themselves because they heard about the program from local advertisements or through community contact, such as through a local National Multiple Sclerosis Society chapter meeting. Most of the patients paid for the program with private funds. The clinical pattern of the course of MS for each patient was classified using standardized definitions described by Lublin and Reingold.22 In this sample, the majority of people were classified as relapsing-remitting (71%) or secondary progressive (20%). Most (96%) had had MS for more than 3 months, and all had an interest in learning more about their disease and how to better manage its effects. The majority of patients who volunteered for the wellness program were independent community-dwelling adults. One patient required a caregiver at home, and six patients used a scooter or wheelchair to improve mobility when outside the home.

Participant characteristics

Research Design

The sample was one of convenience. Analyses were retrospective from a longitudinal, prospective observational cohort design. The Focus On Therapeutic Outcomes, Inc (FOTO) Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects approved the project. Because the analyses were retrospective and related to blinded data used for routine treatment, no patient consent forms were necessary.

Measures

Measures were selected because they assess the effect of several constructs of interest for people with MS and were available in the FOTO computerized database. The database has been described previously.7 21 Briefly, while in the clinic, patients enter demographic, functional status, and a variety of clinician-selected data into a computer. Staff members enter other demographic, clinical, and administrative data into the computer using the same software. Data are aggregated into a database that can be mined as needed.

Functional Status

We assessed functional status using CAT technology23 based on the modern psychometric techniques of IRT.24 Detailed discussion of CAT is beyond the scope of this article.7 23 Briefly, the item bank for the CAT application was developed using items from the 36-item Short Form Health Status Survey (SF-36) physical functioning scale25 and items representing lower-level functioning.26 Eighteen items were calibrated into a unidimensional scale, and the CAT application was developed to improve administrative efficiency while maintaining measure precision at the examinee level. Each item is presented by the computer to the patient starting with the stem “Does or would your health limit,” followed by an activity, such as “Getting in and out of a chair,” followed by three response choices: “Yes, limited a lot,” “Yes, limited a little,” and “No, not limited at all.” In CAT, unlike when giving each person the same fixed test (traditional paper and pencil questionnaire), an item of median difficulty is asked first. Subsequent items are selected by the computer according to the patient's ability, which is estimated given the examinee's responses. Thus the number of items administered and the examinee's response burden are reduced while measure precision is maintained.

Internal consistency reliability of the CAT items has been shown to be strong (Cronbach α = 0.92). The CAT application estimates linear measures of functional status that range from 0 (low functioning) to 100 (high functioning) and have been shown to have good known group construct validity, predictive validity, and sensitivity to change for large samples of patients with neurologic impairments such as cerebrovascular accidents and traumatic brain injuries. Functional status, as assessed using CAT, is operationally defined as the person's perception of their ability to perform daily functional tasks. As estimated, the functional status measure represents the “activity” dimension of the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

Fear-Avoidance Beliefs of Physical Activities

The FABQ scale used for this study has been described previously.10 Briefly, Hart et al.10 assessed the original FABQ8 items using modern psychometric methods20 and identified one item that could be used to classify patients into elevated versus not elevated fear at intake. Starting with the stem “This is a statement other patients have made. Please rate your level of agreement,” the triage item “I should not do physical activities which (might) make my pain worse” is presented. Seven response choices from “Completely disagree” to “Unsure” to “Completely agree” were presented to the patient. Patients who selected “Unsure” to “Completely agree” were classified as “elevated” in their fear-avoidance beliefs of physical activities. Patients who selected other response choices were classified as “not elevated” in their fear-avoidance beliefs. The findings support strong diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity = 0.82, specificity = 0.98, positive likelihood ratio = 34.88, negative likelihood ratio = 0.18) of this method for people with elevated fear regardless of diagnosis, including MS. When the single triage item was administered and found to represent low fear, no other items were administered. When the person's response to the triage item represented elevated fear, the other three FABQ items were administered, which produced a more precise measure of fear-avoidance ranging from 0 (low fear) to 100 (high fear). Using the FABQ assessment process produces two results: 1) a classification of elevated versus not elevated fear-avoidance beliefs of physical activities, which can be used by the clinician to treat people differently depending on whether elevated fear was identified; and 2) a linear measure of fear-avoidance beliefs of physical activities, which could be tracked over time, since reduced fear during therapy has been associated with better functional status outcomes in patients with spinal impairments. There are no similar data for people with MS.

Depression, Somatization, and Risk of Psychological Distress

We assessed depression and somatization using the Symptom Checklist 90–Revised (SCL-90-R).27 The SCL-90-R is commonly used in studies of people with MS.5 Each of ten items is presented with the stem “In the last day, how much were you distressed by” followed by an item to assess depression, such as “worrying too much about things,” and seven items are used to assess somatization, such as “a heavy feeling in your arms or legs.” Both depression and somatization are scored on a scale of 0 to 4, with higher scores representing more depression or somatization. Reports of reliability and validity of the depression and somatization measures have been published.28 In addition, we followed the model of Dionne,29 in which depression and somatization scores are combined to form a categorical risk variable used to classify people with psychological distress (ie, low, intermediate, or high). There are no studies using this distress risk model for people with MS, but the model has been predictive of long-term back-related functional limitations.29

Fatigue

Fatigue is routinely assessed using the MFIS.18 The MFIS is a 21-item patient self-report test. Respondents see the stem “Because of my fatigue in the past 4 weeks,” and then one item at a time is presented, such as “I have been less alert.” There are five response choices: “Almost never,” “Rarely,” “Sometimes,” “Often,” and “Always.” Summing responses produces scores ranging from 0 (low fatigue) to 84 (high impact of fatigue). Scores have been shown to be reliable,18 with a good reproducibility intraclass correlation coefficient of >0.8418; and valid,14 15 with MFIS scores able to discriminate between people with and those without MS and a cut score of 59 or higher having diagnostic accuracy of 81% sensitivity and 77% specificity.15

Pain

We assessed pain intensity using a numeric (0 to 10) pain scale, with higher values representing more pain. The respondent is asked to “Rate the level of pain you have had in the past 24 hours” and selects a number from 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as it can be). The pain intensity estimate from a numeric pain scale has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity.30

Intervention: MS Wellness Program

The MS Wellness Program involved a group of 6 to 12 people with MS who met for one 5-hour session weekly for 12 weeks (details available in the Appendix to this article at www.ijmsc.org). Our sample size was determined by the total number of adults attending and completing the first eight consecutive wellness programs conducted at CentraState Medical Center between June 2008 and December 2010. Only one patient dropped out because of a medical problem and was not included in this study. Each 5-hour session was organized to include the following: 1 hour of light, purposeful exercise; 1 hour of stretching, strength training, or aquatic exercises; 2 hours of topical presentations and discussion; lunch; and homework review and discussion. Purposeful exercise emphasized introduction to physical activities, progressed to demonstrating upper and lower body stretches and strengthening exercises based on patients' level of ability, and finished with a review of symptoms related to MS such as numbness, pain, spasticity, balance problems, and urinary tract infection and methods of treatment. Discussion topics ranged from determining appropriate levels of individualized activities, to defining and calculating individual body mass index, to the importance of maintaining an overall balance of physical, social, spiritual, and emotional well-being. The class finished with group discussion.

The overall tenor of the classes and the wellness program was one of active participation. Each participant received a journal at intake and was encouraged to keep detailed records. On the first day of class, they are asked to record any benefits and goals they hoped to achieve by the end of the classes. Homework was given weekly and recorded in the journals. Homework consisted of thought-provoking questions used to reinforce class activities, such as “What foods can I add to my diet to ensure proper nutrition?” Those willing to share their entries did so at the next class meeting. The wellness program coordinator recruited and screened participants, scheduled classes and instructors, and facilitated weekly activities. There were a total of nine instructors (minister, registered nurse, exercise trainer, occupational and physical therapist certified in MS rehabilitation, dietitian, clinical psychologist, Reike credentialed instructor, and social worker) used for the topical presentations. The same nine instructors were used for all eight wellness programs.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize all measures, including frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations, medians, minimums, maximums, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) where appropriate. For change scores, we subtracted either the intake from the discharge (ie, functional status change) or the discharge from the intake (ie, MFIS), depending on which method provided a positive change that represented a better outcome. For discussion, we transformed each change score into a standardized value by calculating Cohen's d (d) = [(change score)/(pooled standard deviation of intake (s 1) or discharge (s 2) scores)], where the pooled standard deviation (s) is calculated as , and each n was the sample size for intake (n 1) and discharge (n 2) data. Cohen's d represents a distribution-based method of assessing sensitivity to change of a measure based on the statistical characteristics of scores of the sample. A common way to categorize Cohen's d statistics is by using Cohen's definitions of small (≤0.2), medium (>0.2 and ≤0.5), and large (>0.5). The 95% CIs were estimated for each Cohen's d. One-sample t tests on the change scores (H0 [null hypothesis] = 0) with Bonferroni corrections were used to determine whether there were differences in change scores. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to determine whether there were differences in discharge functional status between people whose risk of psychological distress favorably changed (eg, high to low risk) and people whose psychological distress risk increased or remained high over the course of the wellness program. Intake functional status was the covariate. The level of statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

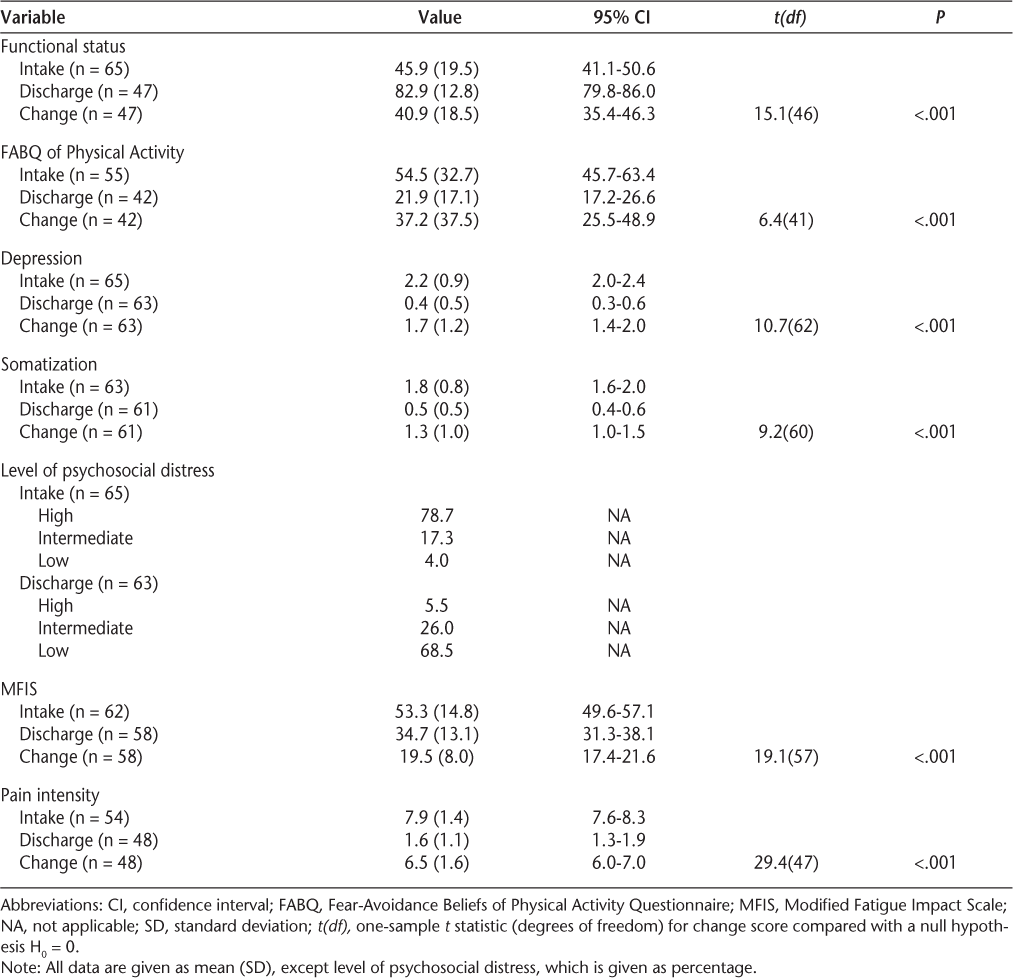

The patients received 12 visits over 12 weeks. Descriptive statistics for all construct measures and change analyses are displayed in Table 2. Although we consider these to be pilot data and the sample size to be small, the results are positive. For example, considering the 95% confidence intervals and Cohen's d statistics, intake-to-discharge comparisons were significant (P < .05) for functional status (d = 2.72; 95% CI, −0.94–7.78), fear-avoidance beliefs of physical activities (d = 1.62; 95% CI, −7.34–6.79), depression (d = 2.35; 95% CI, 2.13–2.48), somatization (d = 1.81; 95% CI, 1.61–1.94), fatigue (d = 1.39; 95% CI, −2.27–4.76), and pain intensity (d = 4.53; 95% CI, 4.11–4.84). Change score t-statistic analyses supported the descriptive statistics. In addition, patients who reported reduced risk of psychological distress from intake to discharge reported higher discharge functional status (adjusted least squares mean 83.8, SE 2.1) compared with patients whose risk of psychological distress did not decrease (adjusted least squares mean 72.4, SE 4.0) (P = .017).

Measures of various constructs

Discussion

We have described a new wellness program based on conservative rehabilitation principles designed to facilitate positive health choices throughout the course of MS and presented initial results, which we consider preliminary. If the initial findings can be replicated in a larger sample over a longer follow-up period, the program appears to be accomplishing our goal: participants appear to be reporting functional and psychosocial improvements as well as less fatigue, which may imply that they are making positive health choices considered important to people with MS. However, given the study's descriptive design and lack of a control group, it cannot be determined if the wellness program yielded any positive outcomes in this sample.

The wellness program was specifically designed for adults with MS whose status was declining or predicted to decline. Because MS has a profound impact on many aspects of a person's life, the program's content and measures used to examine treatment effectiveness included several constructs, including physical functioning and emotional well-being. The favorable results observed in our study are consistent with the results reported for other conservative intervention programs that used similar treatment content designs for adults with MS.17 31 32 For example, interventions focusing on either physical exercise32 or educational programs17 31 have demonstrated an equally positive impact on fatigue, depression, and/or quality of life issues for people with MS.

We are optimistic but not certain that the positive changes observed in this study in all constructs assessed were the result of participation in the program, which used a group format to address these constructs. Thus, one possible testable hypothesis is that the group format may have allowed bonding between group members, resulting in a supportive environment and willingness of participants to share emotional issues, such as struggles and successes associated with dealing with their illness. Participants were rewarded with positive feedback by the class coordinator for successes related to goal accomplishment and implementation of behavioral changes at home. Other programs designed for adults with MS have also reported favorable results when a group treatment format was implemented.32 However, future prospective studies with stronger designs are needed to confirm these results.

In another conservative rehabilitation program designed to improve people's ability to manage fatigue associated with MS, the “Fatigue: Take Control” program,17 participants reported improvement in fatigue using the MFIS and self-efficacy as assessed with the Multiple Sclerosis Self-Efficacy Scale (MSSE).33 Although the MSSE was not used to assess self-efficacy in the current study, the FABQ scale could provide insight into how people perceive fear related to performing physical activities,10 which may be considered a proxy for self-efficacy. Our sample reported good improvement in functional status, fatigue, and perception of fear of performing physical activities. Our findings are consistent with those of other researchers.17 33 Our group is considering the addition of the MSSE to our list of constructs assessed for future data collection.

Interestingly, Cohen's d values for each of the change scores assessed were strong, ranging from 1.39 to 4.53. These values are considered large in any categorical interpretation and were supported by t-test statistics. We are uncertain if this amount of change can be maintained as our sample size increases, but the initial results suggest improvements in multiple constructs for the wellness program participants. Because MS is a complex disorder1 13 with interdependent physical and psychological symptoms,11 most of which cannot be clearly delineated, future studies using a diverse data set should be designed to determine which combinations of constructs are associated, which are important to people with MS as assessed using multivariate models to predict positive outcomes, and which can be successfully managed with targeted interventions.

Development of such a diverse database creates a data-collection burden for all involved—staff, clinician, and patient. The only way to develop a robust, diverse database is through computerization that takes advantage of sophisticated CAT applications23 developed using IRT methods20 designed to reduce respondent burden while maintaining measure precision. The current wellness program takes advantage of computerization and CAT as well as an IRT-based single-item triage scale for fear-avoidance beliefs of physical activities10 that have been shown to be helpful with other psychosocially complex patient populations. Use of CAT and single-item screens reduces the burden associated with assessments of multiple constructs.7 10 21 Given our positive experience with the wellness program and the software used to collect the data, we recommend that complex data sets like the one described here be used to develop large databases from which the interdependence of multiple constructs affecting people with MS can be examined and treatments associated with better outcomes for individual patients can be determined.21

Given the interest in assessing multiple constructs for people with MS, future investigations should provide insight into how to select measures that represent the most important “outcomes” for people with MS participating in wellness programs. For example, most outpatient rehabilitation programs emphasize improvements in functional status, but such improvements may not be the most important sign of the success of an intervention program. Many researchers investigating MS patient population characteristics study constructs such as fatigue,14–17 depression,4 16 somatization,5 11 13 34 self-efficacy,17 33 fear,10 pain,30 and functional status. However, these constructs should not be considered independent. Therefore, these and other constructs and combinations of these constructs should be screened and documented in order to fully examine the benefits of intervention. One example from our pilot data was not only the prevalence of high (79%) psychosocial distress of the wellness participants at intake but the reduction in the prevalence of this level of distress by the end of the program (6%). In addition, for those whose psychosocial distress decreased over the course of the program, there was a concomitant improvement in functional status. Hence, programs should assess more than one construct, such as fatigue, when assessing the benefits of treatment.17 Future directions for our program will include determining which constructs and combinations of constructs are important to people with MS.

We have learned that attention to detail is needed to reduce the amount of missing data for our wellness program participants. This would improve the internal validity and generalizability of our data, particularly as more constructs are added. Steps are under way to test the use of standardized scripts for staff to educate participants on the value of the data in order to encourage the provision of complete data. Moreover, clinicians are endeavoring to use the data during the wellness program to demonstrate the value of the data to clinicians, participants, referral sources, and local MS organizations. The constructive external criticism that can be gained through such exposure can be used to improve the program.

Limitations

Our results were determined at the time of discharge and therefore are short-term. There is evidence that improvements observed during treatment for MS patients decline over time. Wiles et al.35 reported that treatment benefits lasted only a few weeks after intervention completion and recommended that rehabilitation be continuous or repeated to achieve long-term benefits. The optimal dose of treatment and intervals between treatment episodes are unknown and require continued research. In addition, cognitive impairment was not formally assessed in our wellness program. Cognitive impairment has been shown to be a negative predictor of treatment outcome.36 We are exploring adding objective assessment of cognitive impairment to our program to identify patients who may and may not benefit from the program.

Our sample tended to be homogeneous with respect to race (mostly white), ethnicity (mostly non-Hispanic), and MS classification (mostly relapsing-remitting). A more diverse sample would improve the generalizability of our data and would allow more detailed questions to be answered. The participants were primarily private-pay, meaning that many people with MS who might have benefited from the program but did not have the money to attend were not included. Future efforts should strive to make the program affordable to as many people in the community as possible, regardless of means. Because this study had a descriptive design, did not use a control group or randomization, and did not select patients randomly for participation, patient selection bias is likely to have occurred. Patient selection bias can negatively affect statistical results and make interpretation of results almost impossible. Stronger study designs are required before any efficacy hypotheses can be asked and answered, so we do not know whether any positive results can be attributed to the wellness program. However, other conservative treatment programs for people with MS examined using stronger research designs support our program's content and initial favorable results. Finally, future study is required to examine the generalizability of our results using different wellness program facilitators and instructors.

Conclusion

Serial measures of multiple domains for people with MS who attended a multidimensional wellness program in this pilot study suggested improvements in functional status, fear-avoidance of physical activities, depression, somatization, fatigue, and pain. The results suggest a positive impact on people with MS, but the descriptive design did not allow confirmation. Strengths and areas in need of improvement in the program were identified, and plans were developed to improve the program.

PracticePoints

A multidimensional wellness program for people with MS was developed to facilitate positive health choices throughout the course of their chronic disease.

The wellness program included educational sessions in physical, mental, social, intellectual, and spiritual domains specifically targeting improved self-efficacy, physical functioning, coping skills, symptom management, and nutrition.

Initial assessment of serial measures of functional status, fear-avoidance of physical activities, depression, somatization, fatigue, and pain suggested a positive impact for each domain.

Analyses were used to identify strengths and areas in need of improvement in the wellness program.

References

Fleming JO, Carrithers MD. Diagnosis and management of multiple sclerosis: a handful of patience. Neurology. 2010; 74: 876–877.

Bejaoui K, Rolak LA. What is the risk of permanent disability from a multiple sclerosis relapse? Neurology. 2010; 74: 900–902.

Fjeldstad C, Pardo G, Frederiksen C, Bemben D, Bemben M. Assessment of postural balance in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2009; 11: 1–5.

Johnson SK, DeLuca J, Natelson BH. Personality dimensions in the chronic fatigue syndrome: a comparison with multiple sclerosis and depression. J Psychiatr Res. 1996; 30: 9–20.

Bruce AS, Arnett PA. Longitudinal study of the symptom checklist 90-revised in multiple sclerosis patients. Clin Neuropsychol. 2008; 22:46–59.

Vercoulen JH, Hommes OR, Swanink CM, et al. The measurement of fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: a multidimensional comparison with patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and healthy subjects. Arch Neurol. 1996; 53: 642–649.

Hart DL, Deutscher D, Werneke MW, Holder J, Wang YC. Implementing computerized adaptive tests in routine clinical practice: experience implementing CATs. J Appl Meas. 2010; 11: 288–303.

Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993; 52: 157–168.

George SZ, Fritz JM, Bialosky JE, Donald DA. The effect of a fear-avoidance-based physical therapy intervention for patients with acute low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2003; 28: 2551–2560.

Hart DL, Werneke MW, George SZ, et al. Screening for elevated levels of fear-avoidance beliefs regarding work or physical activities in people receiving outpatient therapy. Phys Ther. 2009; 89: 770–785.

Harris AM, Orav EJ, Bates DW, Barsky AJ. Somatization increases disability independent of comorbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2009; 24: 155–161.

Haggman S, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. Screening for symptoms of depression by physical therapists managing low back pain. Phys Ther. 2004; 84: 1157–1166.

Pavlou M, Stefoski D. Development of somatizing responses in multiple sclerosis. Psychother Psychosom. 1983; 39: 236–243.

Hadjimichael O, Vollmer T, Oleen-Burkey M. Fatigue characteristics in multiple sclerosis: the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008; 6:100.

Kos D, Nagels G, D'Hooghe MB, Duportail M, Kerckhofs E. A rapid screening tool for fatigue impact in multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2006; 6:27.

Flachenecker P, Kumpfel T, Kallmann B, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a comparison of different rating scales and correlation to clinical parameters. Mult Scler. 2002; 8: 523–526.

Hugos CL, Copperman LF, Fuller BE, Yadav V, Lovera J, Bourdette DN. Clinical trial of a formal group fatigue program in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010; 16: 724–732.

Kos D, Kerckhofs E, Carrea I, Verza R, Ramos M, Jansa J. Evaluation of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale in four different European countries. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 76–80.

Jensen MP, Romano JM, Turner JA, Good AB, Wald LH. Patient beliefs predict patient functioning: further support for a cognitive-behavioural model of chronic pain. Pain. 1999; 81: 95–104.

van der Linden W, Hambleton RK, eds. Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 1997.

Deutscher D, Horn SD, Dickstein R, et al. Associations between treatment processes, patient characteristics, and outcomes in outpatient physical therapy practice. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009; 90: 1349–1363.

Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 1996; 46: 907–911.

Wainer H, ed. Computerized Adaptive Testing: A Primer>. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000.

Hambleton RK, Swaminathan H, Rogers HJ. Fundamentals of Item Response Theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991.

Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992; 30: 473–483.

Hart DL, Wright BD. Development of an index of physical functional health status in rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002; 83: 655–665.

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983; 13: 595–605.

Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: a step in the validation of a new self-report scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1976; 128: 280–289.

Dionne CE. Psychological distress confirmed as predictor of long-term back-related functional limitations in primary care settings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005; 58: 714–718.

Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Fisher LD. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain. 1999; 83: 157–162.

Craig J, Young CA, Ennis M, Baker G, Boggild M. A randomised controlled trial comparing rehabilitation against standard therapy in multiple sclerosis patients receiving intravenous steroid treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003; 74: 1225–1230.

Solari A, Filippini G, Gasco P, et al. Physical rehabilitation has a positive effect on disability in multiple sclerosis patients. Neurology. 1999; 52: 57–62.

Rigby SA, Domenech C, Thornton EW, Tedman S, Young CA. Development and validation of a self-efficacy measure for people with multiple sclerosis: the Multiple Sclerosis Self-Efficacy Scale. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 73–81.

Hilty DM, Bourgeois JA, Chang CH, Servis ME. Somatization disorder. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2001; 3: 305–320.

Wiles CM, Newcombe RG, Fuller KJ, et al. Controlled randomised crossover trial of the effects of physiotherapy on mobility in chronic multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001; 70: 174–179.

Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology. 1991; 41: 685–691.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Hart is an investor in and employee of Focus On Therapeutic Outcomes, Inc (FOTO), an international proprietary database management company. Analyses of data such as those in this study are part of his normal daily activities. Ms. Memoli, Dr. Mason, and Mr. Werneke are employees of CentraState Health-care System, which uses the FOTO outcomes system as part of the System's routine patient-care management process. Ms. Memoli, Dr. Mason, and Mr. Werneke have no financial relationship with FOTO.

Note: Supplementary material for this article (a list of additional references and an Appendix containing details of the wellness program) is available on IJMSC Online at www.ijmsc.org.