Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Comparing Two Conditions of Administering the Six-Minute Walk Test in People with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Objective: This quasi-experimental study was conducted to determine whether differences existed in the total distance walked and energy expended between two conditions of administering the 6-Minute Walk test (6MW) across different levels of disability in people with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Methods: The sample comprised 160 individuals with MS. One group of participants (n = 82) completed a 6MW while wearing a portable metabolic unit (K4b2, Cosmed, Italy) in a square hallway with four corridors and performing 90° turns. Another group (n = 78) completed a 6MW while wearing the same metabolic unit in a single corridor and performing 180° turns. Main outcome measures included total distance walked (in feet) and oxygen consumption (in milliliters per minute) expressed as 30-second averages for 1 minute before the 6MW and over the entire 6MW. Disability status was assessed using the Patient-Determined Disease Steps scale.

Results: Participants undertaking the 6MW in a single corridor (1412 ft) walked 37 ft (2.7%) farther than those undertaking the test in a square hallway (1375 ft), but this difference was not statistically significant (F = 0.45, P = .51). Those completing the 6MW in a single corridor expended more energy than those completing the 6MW in the square hallway with four corridors (F = 3.41, P < .01).

Conclusions: Either protocol is acceptable, but researchers should be aware of the additional physiological demands when administering the 6MW in a single corridor with 180° turns.

Walking impairment is a common and life-altering feature of both early and advanced multiple sclerosis (MS)1 2 and is commonly measured using performance tests such as the 6-Minute Walk test (6MW) and the Timed 25-Foot Walk (T25FW).3 The 6MW, in particular, provides a measure of walking endurance in people with MS.3–6 The distance traveled during the 6MW has differentiated between those with MS and healthy controls4 7 and across stages of disability in MS samples.4 8 There is further evidence that the 6MW may be more precise in defining disability than other measures of walking performance such as the T25FW.4

Researchers have standardized 6MW instructions regarding participant effort/behavior (ie, walking as fast and as far as possible without stopping for rest) and researcher behavior (ie, no encouragement)4 when the 6MW is administered in individuals with MS. To date, there has been no standardization of the walking-course conditions for the 6MW in MS. One walking-course condition involves walking laps within a single corridor and performing 180° turns (ie, straight-line course),4 9 10 whereas another involves walking laps around a square hallway with four corridors and performing 90° turns (ie, square course).7 8 These different conditions of administering the 6MW may influence the total distance traveled and/or the associated amount of energy expended by individuals with MS, particularly as a function of disability status (involving lesser or greater walking impairment). Although no such comparisons between 6MW conditions have been made in MS, one study in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) reported that 6MW distance was significantly greater when the test was completed on a continuous track (ie, oval or square administration) than when it was completed in a straight-line course.11 One limitation of that study was that the instructions were not standardized as in MS (ie, walking as fast and far as possible without rest or encouragement for 6 minutes). Moreover, that study did not measure energy expenditure to examine the metabolic demands of each 6MW administration.

The current study adopted a quasi-experimental design and compared the total distance walked and energy expended between two conditions of administering the 6MW (ie, “straight-line” or “square” 6MW courses) with standardized instructions across two different levels of disability in individuals with MS: those with and those without gait impairment. We hypothesized that participants undertaking the “straight-line” 6MW would walk a shorter distance and expend more energy than those undertaking the “square” 6MW based on evidence in COPD11 and the logic that 180° turns presumably require more frequent deceleration/acceleration and a greater change of direction than 90° turns. The study also examined the comparable validity of each 6MW administration by assessing associations among 6MW distance and disability status, objectively measured walking performance, and self-reported walking impairment. We hypothesized that distance traveled from each 6MW administration would be strongly associated with those outcomes. If our hypotheses are supported, such information might further inform the ongoing dialogue regarding the demands of administering the 6MW in MS research.

Methods

Participants

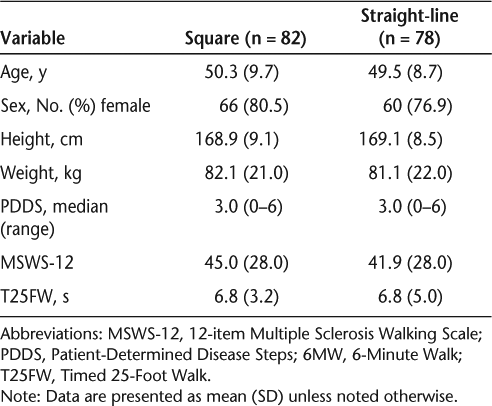

This study involved a quasi-experimental design in which we compared data collected from two separate investigations of people with MS. The first dataset was from the baseline testing session of an ongoing behavioral intervention for increasing physical activity, and the second was from a cross-sectional study of physical activity and imaging outcomes. Recruitment for both studies was undertaken concurrently, and testing was completed by the same assessors at two different sites; this afforded an opportunity to compare between the conditions of administering the 6MW. Participants in both studies were recruited by 1) mail through a flyer that was distributed to patients in the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) registry; 2) e-mail through a flyer that was distributed to participants in a database from previous studies conducted in our laboratory over the past 5 years; or 3) announcements in local media outlets, promotional flyers, and direct invitation based on medical records. A total of 402 participants initially expressed interest in both studies and were contacted via telephone by the project coordinator. After explaining the study protocols, the project coordinator undertook screening for inclusion, the criteria for which were 1) definite diagnosis of MS (participants provided a physician’s verification of MS diagnosis); 2) relapse-free status for the past 30 days; 3) ability to walk with or without an assistive device (ie, cane, crutch, or walker); and 4) willingness and ability to travel to the testing site to complete the 6MW among other measures. Of the 402 people who were screened, 242 did not meet the inclusion criteria, with the primary reason being unwillingness to travel to the testing site(s) due to scheduling conflicts. This resulted in a final sample of 160 individuals with MS. Eighty-two participants were enrolled into the cross-sectional study (ie, “square” group) and 78 were enrolled into the behavioral intervention (ie, “straight-line” group) (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of 160 individuals with MS completing two different conditions of the 6MW

Measures

Six-Minute Walk Test

Participants were instructed to walk as fast and as far as possible without rest or encouragement for 6 minutes (ie, standardized instructions for 6MW administration in MS)4; when necessary, participants were permitted to use an assistive device for both conditions of administering the 6MW (ie, “straight-line” and “square”). The “straight-line” 6MW was completed within a single corridor measuring 75 ft in length, with cones placed on opposite ends, while performing 180° turns around the cones. The “square” 6MW was completed in a square hallway with four corridors, each measuring 100 ft in length, while performing 90° turns around corners. One researcher followed approximately 3 ft behind the participant with a measuring wheel (Stanley MW50, New Briton, CT) and recorded total distance traveled as the primary outcome measure of the 6MW for both 6MW conditions.

Oxygen Consumption

Energy expenditure was expressed based on oxygen consumption (V̇o2) and measured breath by breath during the 6MW using a commercially available portable metabolic unit (K4b2, Cosmed, Italy). The O2 and CO2 analyzers of the portable metabolic unit were calibrated using verified concentrations of gases, and the flow-meter was calibrated using a 3-L syringe (Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, MO). Oxygen consumption (milliliters per minute) was calculated as 30-second averages for 1 minute before the 6MW and over the entire 6MW.

Walking Performance

The 12-item Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (MSWS-12) and T25FW were used as additional measures of walking performance in both samples as outcomes for establishing group equivalence in walking functions. The T25FW was administered as a measure of walking speed; participants walked 25 ft as quickly and safely as possible in a hallway clear of debris over two trials.12 The main outcome measure was the mean time (seconds) taken to complete the T25FW on two trials.12 The MSWS-12 is a 12-item patient-rated measure of the impact of MS on walking.13 The 12 items on the MSWS-12 are rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The total MSWS-12 score ranges from 0 to 100 and is computed by summing the individual item scores, subtracting the minimum possible score of 12, dividing by 48 (ie, the maximum score on the summed items after subtracting the minimum possible score), and then multiplying the result by 100.13

Disability Status

The Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) scale14 was included as a measure of disability level for further establishing group equivalence in disability status. The PDDS is a self-report outcome that was developed as an inexpensive surrogate to clinical assessments of disability (eg, Expanded Disability Status Scale; EDSS). The PDDS contains a single item for measuring self-reported neurologic impairment on an ordinal level, ranging from 0 (normal) through 8 (bedridden). This scale has been reported to be valid based on a strong correlation with the physician-administered EDSS.14 We then formed groups of 72 individuals without gait disability and 88 individuals with gait disability based on PDDS scores of 0 to 2 and 3 to 6, respectively15; 37 individuals without gait disability completed the “square” 6MW while 35 participants completed the “straight-line” 6MW. Further, 45 people with gait disability completed the “square” 6MW and 43 completed the “straight-line” 6MW.

Protocol

Both of the protocols were approved by university institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent. The protocols were completed at different testing sites, but included a single session for collecting all data. All participants initially completed a battery of questionnaires including a demographics inventory, MSWS-12, and PDDS. Participants then completed two trials of the T25FW, followed by 10 minutes of seated rest. During this rest period, participants were fitted with the portable metabolic system. Once wearing the system, participants were given standardized instructions for undertaking the 6MW. Participants subsequently completed the 6MW in either a “square” hallway or a “straight-line” corridor. We provided a $15 gift card to cover travel expenses upon completion of data collection.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). We first examined differences between “square” and “straight-line” groups in terms of age, sex, height, weight, disability status, T25FW performance, and MSWS-12 scores (ie, possible variables that might differ between samples and confound the comparison of conditions for administering the 6MW) using independent-samples t tests or χ2 difference tests. We performed Spearman rho nonparametric rank-order correlations among 6MW distance and PDDS scores, T25FW performance, and MSWS-12 scores for establishing comparable validity of each condition of 6MW administration; we used nonparametric correlations to determine whether outliers or nonlinearity was biasing the associations among variables. We performed a 2 (6MW administration: square vs. straight-line) by 2 (disability status: no gait disability vs. gait disability) analysis of variance (ANOVA) on total distance walked during the 6MW. We further performed a similar 2 (6MW administration: square vs. straight-line) by 2 (disability status: no gait disability vs. gait disability) ANOVA with repeated measures on all 12, 30-second V̇o2 averages over the course of the 6MW and controlling for resting energy expenditure as a covariate.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics for both the “square” and “straight-line” groups are presented in Table 1. The groups did not differ in terms of age (t = 0.55, P = .59), sex (χ2 = 0.30, P = .58), height (t = −0.09, P = .93), weight (t = 0.29, P = .77), PDDS scores (t = −0.39, P = .70), MSWS-12 scores (t = 0.72, P = .47), or T25FW performance (t = 0.02, P = .98). Such initial group equivalence is important considering the quasi-experimental design of the study.

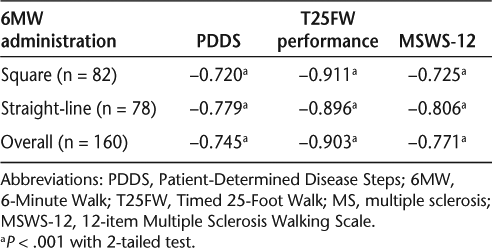

Correlations Among 6MW Distances and Clinical Measures

Six-Minute Walk distances for the square and straight-line administrations, as well as for both administrations combined, were significantly and similarly associated with disability status, T25FW performance, and MSWS-12 scores (Table 2).

Correlations among 6MW distance and PDDS scores, T25FW performance, and MSWS-12 scores in people with MS

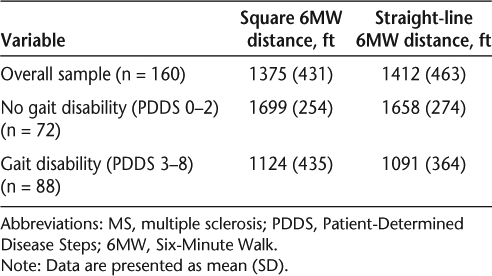

Six-Minute Walk Distance

There was not a significant 6MW administration × disability status interaction on distance traveled (F 1,156 = 0.01, P = .93, partial-η2 < 0.01). This indicated that there was no difference in distance walked between conditions of 6MW administration as a function of disability status. Further, there was not a significant main effect for 6MW administration on distance traveled (F 1,156 = 0.45, P = .51, partial-η2 < 0.01). Participants undertaking the “straight-line” 6MW in a single corridor walked 37 ft (2.7%) farther (1412 ft) than those undertaking the “square” 6MW (1375 ft) (Table 3). That difference was not clinically meaningful,16 and the condition of 6MW administration explained less than 1% of the variance in 6MW distance. There was a significant main effect for disability status (F 1,156 = 107.87, P < .01, partial-η2 = 0.41), indicating that across 6MW conditions those without gait disability walked significantly farther (571 ft, 51.6%) than those with gait disability. This main effect explained a noteworthy 41% of the variance in 6MW distance.

6MW distances based on administration condition and disability status in people with MS

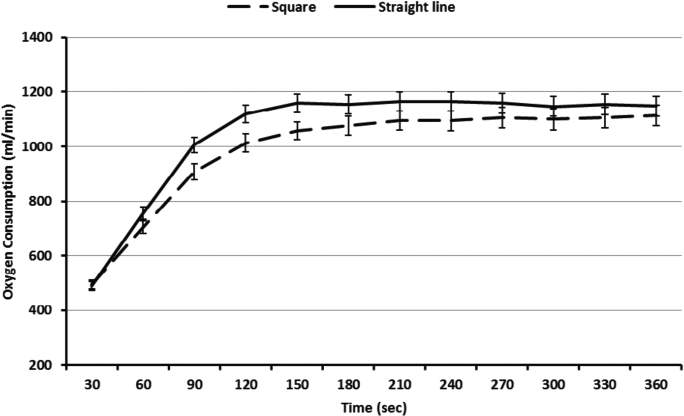

Six-Minute Walk Energy Expenditure

Overall, when controlling for resting metabolic rate as a covariate, there was not a 3-way 6MW administration × disability status × time interaction on V̇o2 (F 11,1705 = 0.23, P = .99, partial-η2 < 0.01). This indicated that change in energy expenditure over time did not differ based on 6MW administration between levels of disability status. There was a significant time × disability status interaction on V̇o2 (F 11,1705 = 9.52, P < .01, partial-η2 = 0.06; Figure 1), indicating that those without gait disability expended more energy initially (first 3 minutes of 6MW) and then maintained this higher level of energy expenditure over the remainder of the 6MW compared to those with gait disability; the interaction explained 6% of the variance in V̇o2. There was a small but statistically significant time × 6MW administration interaction on V̇o2 (F 11,1705 = 3.41, P < .01, partial-η2 = 0.02). This indicated that those completing the “straight-line” 6MW expended more energy over the first 3 minutes of the 6MW than those completing the “square” 6MW, and energy expenditure then remained steady over the last 3 minutes of the 6MW (Figure 2). This interaction explained 2% of the variance in V̇o2.

Energy expenditure in people with MS over the duration of the 6MW with (n = 88) and without (n = 72) gait disability

Energy expenditure in people with MS over the duration of the 6MW under square (n = 82) and straight-line (n = 78) hallway conditions

Discussion

The primary novel finding of this quasi-experimental, cross-sectional study was that energy expenditure, but not total distance traveled, differed when the 6MW was administered in a single, straight-line corridor with 180° turns compared with a square hallway consisting of four corridors and 90° turns. That pattern of results was not influenced by disability status. The greater energy expenditure for the “straight-line” 6MW versus the “square” 6MW primarily occurred in the first 3 minutes of the 6MW and was small in magnitude. Such results suggest that both administrations of the 6MW yield similar end results regarding distance walked, but with a slightly higher energy expenditure for the straight-line 6MW condition. This similarity in distance traveled is likely attributable to the standardization of the instructions and researcher behavior for the 6MW in MS4 and indicates that researchers can confidently perform the 6MW under either condition, if using standardized instruction; however, they should be aware that the straight-line administration is slightly more metabolically demanding for participants. This might be attributed to the potentially greater metabolic demand of making 180° turns, requiring more frequent deceleration/acceleration and a greater change of direction than 90° turns. The shorter hallway length of the straight-line administration is a possible explanation for the greater energy expenditure associated with this condition; however, research in COPD suggests that course length does not influence total distance walked during the 6MW.11 Standardized instruction for the 6MW is important, as demonstrated by research in COPD where participants demonstrated a greater distance traveled in a continuous (oval or square) administration than a straight-line administration of the 6MW.11 In that study, however, multiple sites that adopted different instructions for standardizing participant effort and behavior than in MS (ie, delivering standardized encouragement and neglecting to emphasize walking as fast as possible without stopping) were included; moreover, the study did not establish group equivalence in walking dysfunction. We believe that inclusion of MS-specific instructions that standardize participant effort and behavior (ie, walking as fast and far as possible without rest for 6 minutes) will overcome possible differences in 6MW administration such that either method is acceptable in individuals with MS.

Six-minute walk distance was strongly and similarly associated with disability status, T25FW performance, and MSWS-12 scores regardless of condition for administering the 6MW. Such correlations are consistent with previous reports indicating strong associations among 6MW distance and other disability/walking performance measures.4 7 The current results regarding differences in 6MW distance by disability status are also consistent with two previous studies indicating that people with MS who had severe disability walked shorter 6MW distances than those with moderate and mild disability.4 8 The current study generally replicates the findings that, in people with MS, energy expenditure increased during the first 3 minutes of the 6MW before reaching a plateau8 17 and the rate and plateau were greater for those without gait disability than for those with gait disability.8 This consistency is important, as it situates our results within other research in MS, but in a substantially larger sample and across conditions of administering the 6MW.

The current study has several strengths, including the large sample of individuals with MS, objective measurement of energy expenditure, adoption of standardized instructions for 6MW, and replication of previous results regarding the 6MW; however, there are important limitations. Longer walking tests such as the 6MW might result in an increased risk of falls and excessive fatigue in people with MS, but, as previously reported, the 6MW represents a measure of walking endurance in this population3–6 that may be more precise in defining disability than shorter walking tests such as the T25FW.4 One limitation was the quasi-experimental nature of the study. We established that both groups were similar in demographic, clinical, disability, and walking characteristics, but the samples were not matched based on these characteristics or randomized into conditions for administering the 6MW. There may be subtle differences between groups of 6MW administration that account for our results and that were not controlled for in the present analysis (eg, aerobic fitness level or fatigue). Another limitation of the current investigation was the inclusion of a self-reported measure of disability rather than an EDSS score generated by a neurologist as an approach for generating groups by gait disability. Such groups may not purely reflect gait/walking impairment, as other factors such as cognitive impairment could influence PDDS scores. It is important to note that the current study used previously reported standardized instructions of the 6MW4 for consistency, as the majority of research that has included the 6MW as a primary outcome measure in MS has adopted those instructions. We did not compare 6MW performance using the aforementioned standardized instructions4 with alternative instructions allowing rest or providing standardized encouragement. Nevertheless, we provide evidence supporting either condition of administering the 6MW, given the standardized instructions, across a range of disability in people with MS.

Conclusion

Overall, the current study offers novel evidence that energy expenditure, but not total distance traveled, differed when the 6MW was administered in a single corridor with 180° turns compared with a square hallway with four corridors and 90° turns. This did not depend on disability status. These findings suggest that either protocol is acceptable, as total distance traveled is the primary outcome measure of the 6MW, but researchers should be aware of the additional physiological demands when administering the 6MW in a single corridor with 180° turns.

PracticePoints

It is unknown whether alternate conditions of administration of the 6-Minute Walk test (6MW) result in similar total distance traveled and energy expenditure in people with MS.

Overall, the current study offers novel evidence that energy expenditure, but not total distance traveled, differed when the 6MW was administered in a single corridor with 180° turns compared with a square hallway with four corridors and 90° turns; this did not depend on disability status.

These results suggest that either protocol is acceptable, as total distance traveled is the primary outcome measure of the 6MW, but researchers and clinicians should be aware of the additional physiological demands when administering the 6MW in a single corridor with 180° turns.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yoojin Suh and Swathi Balantrapu for assistance in data acquisition. Data from this study were presented as a poster during the 26th Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers held in 2012 in San Diego, California.

References

Heesen C, Segal J, Reich C, et al. Patient information on cognitive symptoms in multiple sclerosis: acceptability in relation to disease duration. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006; 114: 268–272.

Larocca NG. Impact of walking impairment in multiple sclerosis: perspectives of patients and care partners. Patient. 2011; 4: 189–201.

Kieseier BC, Pozzilli C. Assessing walking disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012; 18: 914–924.

Goldman MD, Marrie RA, Cohen JA. Evaluation of the six-minute walk in multiple sclerosis subjects and healthy controls. Mult Scler. 2008; 14: 383–390.

Goldman MD, Motl RW, Rudick RA. Possible clinical outcome measures for clinical trials in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2010; 3: 229–239.

Motl RW. Ambulation and multiple sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2013; 24: 325–336.

Motl RW, Balantrapu S, Pilutti L, et al. Symptomatic correlates of six-minute walk performance in persons with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013; 49: 59–66.

Motl R, Suh Y, Balantrapu S, et al. Evidence for the different physiological significance of the 6- and 2-minute walk tests in multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2012; 12:6.

Savci S, Inal-Ince D, Arikan H, et al. Six-minute walk distance as a measure of functional exercise capacity in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2005; 27: 1365–1371.

Dalgas U, Severinsen K, Overgaard K. Relations between 6 minute walking distance and 10 meter walking speed in patients with multiple sclerosis and stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012; 93: 1167–1172.

Sciurba F, Criner GJ, Lee SM, et al. Six-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: reproducibility and effect of walking course layout and length. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003; 167: 1522–1527.

Fischer JS, Jak AJ, Knicker JE, Rudick RA, Cutter G. Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC): Administration and Scoring Manual. New York, NY: National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2001.

Hobart JC, Riazi A, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, Thompson AJ. Measuring the impact of MS on walking ability: the 12-Item MS Walking Scale (MSWS-12). Neurology. 2003; 60: 31–36.

Hadjimichael O, Kerns RD, Rizzo MA, Cutter G, Vollmer T. Persistent pain and uncomfortable sensations in persons with multiple sclerosis. Pain. 2007; 127: 35–41.

Marrie RA, Goldman M. Validity of performance scales for disability assessment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 1176–1182.

Learmonth YC, Dlugonski D, Pilutti L, Sandroff BM, Motl RW. The reliability, precision and clinically meaningful change of walking mobility assessments in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013; 19: 1784–1791.

Motl RW, Sandroff BM, Suh Y, Sosnoff JJ. Energy cost of walking and its association with gait parameters, daily activity, and fatigue in persons with mild multiple sclerosis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012; 26: 1015–1021.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Motl has been a consultant for Biogen and Acorda, but neither had a role in designing the current study. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.