Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Characterizing Long-term Disability Progression and Employment in NARCOMS Registry Participants with Multiple Sclerosis Taking Dimethyl Fumarate

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF) is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), but long-term effects of DMF on disability and disease progression in clinical settings are unknown. We evaluated disability and employment outcomes in persons with RRMS treated with DMF for up to 5 years.

Methods:

This longitudinal study included US North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry participants with RRMS reporting DMF initiation in fall 2013 through spring 2018 with 1 year or more of follow-up. Time to 6-month confirmed disability progression (≥1-point increase in Patient-Determined Disease Steps [PDDS] score) and change in employment status were evaluated using Kaplan-Meier analysis. Participants were censored at last follow-up or at DMF discontinuation, whichever came first.

Results:

During the study, 725 US participants with RRMS had at least 1 year of DMF follow-up data, of whom most were female and White. At year 5, 69.9% (95% CI, 65.4%–73.9%) of these participants were free from 6-month confirmed disability progression, and 84.7% (95% CI, 78.6%–89.2%) were free from conversion to secondary progressive MS. Of 116 participants with data at baseline and year 5, most had stable or improved PDDS and Performance Scales scores over 5 years. Of 322 participants 62 years and younger and employed at the index survey, 66.0% (95% CI, 57.6%–73.1%) were free from a negative change in employment type over 5 years.

Conclusions:

Most US NARCOMS Registry participants treated up to 5 years with DMF remained free from 6-month confirmed disability progression and conversion to secondary progressive MS and had stable disability and employment status. These results support the long-term stability of disability and work-related outcomes with disease-modifying therapy.

In the past several years, multiple new therapies have emerged for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), including delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF; also known as gastroresistant DMF). The pivotal DEFINE and CONFIRM clinical trials and the ENDORSE extension trial1–5 demonstrated the benefits of DMF with respect to reduction in relapse rate, magnetic resonance imaging outcomes, and disability progression. Health-related quality of life measures improved during 2 years of DMF treatment but worsened with placebo treatment,3 suggesting that DMF improves patient-perceived health status.

As of June 30, 2021, 537,432 patients have been treated with DMF, representing 1,119,293 patient-years of exposure. Of these, 6413 patients (14,292 patient-years) were from clinical trials. Although clinical trials provide a high level of evidence regarding the efficacy of a treatment, there are several potentially important limitations. The populations enrolled may differ from those observed in routine clinical practice. The duration of follow-up is short, limiting inference about medium- and long-term outcomes, particularly related to disability progression. The assessment of patient-reported outcomes and of meaningful functional and participatory outcomes is often limited.

Studies based on real-world data have the potential to address these gaps and provide additional, clinically meaningful evidence to guide treatment decisions made by persons with MS and their health care providers through a shared decision-making model.6 In previous real-world studies, patients treated with DMF had a low annualized relapse rate and risk of relapse, consistent with clinical trial findings.7–9 Real-world studies also demonstrated that patients treated with DMF maintained clinical stability or showed improvement after 12 months of DMF treatment versus baseline with respect to fatigue, activities of daily living, and work impairment.8,9 To date, however, most real-world studies have examined outcomes over periods of 2 years or less only. Thus, there is a lack of data regarding the long-term effects of DMF on disability outcomes, rate of conversion to secondary progressive MS (SPMS), and common symptoms that adversely affect quality of life (eg, cognition, fatigue, depression).

Data are also relatively limited regarding the long-term effects of DMF on employment outcomes. Often, MS is diagnosed between ages 20 and 50 years,10 in the prime of career development; up to half of individuals with MS exit the workforce within 5 years of diagnosis, and two-thirds are unemployed within 15 years.11 Such changes in employment status are associated with reduced quality of life.12 Absenteeism is also an issue for those who remain employed; for example, one study demonstrated that individuals with MS missed four times more workdays in a 1-year period than employees who did not have MS.13 Work productivity improvements have been observed after 12 to 24 months of treatment with DMF.3,8,9,12,14 However, there is little information on the probability of maintaining employment in persons with MS treated with DMF over the long-term.

We aimed to determine the effects of DMF on disability progression, symptom domains, and employment status in persons with RRMS treated for up to 5 years.

Methods

Study Design and Source Population

We conducted a longitudinal cohort study using the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry. Initiated in 1996, the NARCOMS Registry is a voluntary self-report registry for people diagnosed as having MS. Participants confidentially provide information about their demographic characteristics, medical history, and disease and treatment characteristics at enrollment and every 6 months thereafter, either online or on paper, per their preference. The NARCOMS Registry is approved by the Washington University in St Louis institutional review board.

Inclusion Criteria

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they reported initiating DMF on a survey between fall 2013 and spring 2018, completed at least one semiannual follow-up survey approximately 1 year after DMF initiation, and were US residents (Figure S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org). The first survey on which the participant indicated taking DMF was considered the index survey. Participants were excluded if they had SPMS or primary progressive MS at the time of the index survey. This group of participants constituted the overall population; participants were censored at last follow-up or at DMF discontinuation, whichever came first.

We also studied two subpopulations (Figure S1): 1) a 5-year completer population of participants who initiated DMF between fall 2013 and spring 2014 and completed a survey at year 5 reporting that they were still receiving DMF treatment and 2) an employment population of participants who reported being employed full-time or part-time at the index survey and were 62 years and younger. Because the study spans 5 years and the average retirement age in the United States is 62 years,15 the change in employment status in people older than 62 years may more likely be driven by reasons unrelated to MS.

Measures

The Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) scale is a self-report measure for characterizing MS-associated disabilities and disability progression that was adapted from the physician-administered Disease Steps scale. The PDDS is an ordinal scale with scores ranging from 0 (normal) to 8 (bedridden). Results from the PDDS are highly correlated with the clinician-measured Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores.16–19 The Performance Scales (PS) is a self-report measure for MS-associated disability20 assessing eight domains: mobility, bladder/bowel, fatigue, sensory, vision, cognition, spasticity, and hand. Scores for all domains except mobility range from 0 (normal) to 5 (total disability); scores for the mobility domain range from 0 to 6. Both the PDDS and the PS have good internal consistency and reliability and adequate test-retest reliability.16,18 The PS mobility, bladder/bowel, fatigue, vision, and hand subscales have each been validated against their clinical criterion measures (Timed 25-Foot Walk test, Nine-Hole Peg Test, low-contrast visual acuity, Modified Fatigue Impact Scale, and Bladder Control Scale).18 In addition, the NARCOMS depression scale was used to assess depression.21

Demographic information was captured from the participant enrollment survey. Participants reported their sex, date of birth, race (categorized as White, Black, or other), and year of diagnosis on their enrollment survey. Age was calculated as age at the time of the index survey. Each semiannual update used a single question to assess whether the participant had a relapse in the past 6 months (yes/no/unsure). Participants reported their clinical course of MS by responding to the question, “What type of MS has your doctor said you have now?” with possible responses being clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting, secondary progressive, primary progressive, and don’t know/unsure. Previous use of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) was determined based on respondents reporting past use of DMTs, including the following: cyclophosphamide, glatiramer acetate, intramuscular interferon beta-1a, subcutaneous interferon beta-1a, interferon beta-1b, teriflunomide, fingolimod, or natalizumab. Employment status was reported as full-time, part-time, or unemployed. Participants also reported the number of workdays missed and whether the hours they worked had decreased (yes/no).

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest differed by study population. For the overall population, we focused on time to 6-month confirmed disability progression and proportion of participants who converted to SPMS. Time to 6-month confirmed disability progression was defined as a 1-point or more increase in PDDS score sustained for 6 months or longer. For the 5-year completer analysis, the outcomes included change from baseline in PDDS score, the eight PS domain scores, and the NARCOMS depression scale score.

Employment outcomes included time to negative change in employment status, reduction in work hours, missed workdays, and positive employment change. Negative change in employment status was categorized as change from employed full-time at the index survey to part-time; employed full-time at the index survey to unemployed; or employed full- or part-time at the index survey to unemployed. For analysis of missed workdays, we included participants who reported being employed at the index survey and who responded to the survey question regarding missed workdays. The analysis of positive employment change included participants who reported being unemployed at the index survey to determine the proportion of patients who changed from unemployed to employed (part-time or full-time).

Statistical Analysis

We summarized demographic and clinical characteristics for the cohort using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were summarized using mean (SD) or median (minimum, maximum), as appropriate. Categorical variables were summarized using frequency (percentage). Time to 6-month confirmed PDDS score progression, conversion to SPMS, negative change in employment, and reduction in work hours were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Participants were censored at last follow-up or at the time of DMF discontinuation, whichever came first. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Overall Population

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

During the study period, 1058 US NARCOMS Registry participants with RRMS initiated DMF therapy; 725 had at least 1 year of follow-up data (Figure S1). Of these 725 participants, 366 (50.5%) remained on DMF treatment at the time of the analysis. Most participants were female and White, with a median (inter-quartile range [IQR]) age of 53 (46–59) years and disease duration of 14 (8–19) years. More than half of the participants reported previous treatment with a DMT, and one-quarter had experienced a relapse in the 6 months before the index survey. Median DMF treatment duration and follow-up was 3 years (Table S1).

Disability Outcomes

Of the 725 participants assessed, at year 5 69.9% (95% CI, 65.4%–73.9%) were free from 6-month confirmed disability (PDDS score) progression and 84.7% (95% CI, 78.6%–89.2%) were free from conversion to SPMS (Figure 1).

Freedom from 6-month confirmed disability (Patient-Determined Disease Steps score) progression (A) and freedom from conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (B) in overall population (N = 725)

5-Year Completer Subgroup

Participants

From the overall population (N = 725), we identified 116 participants for inclusion in the 5-year completer population (Figure S1). Demographic and baseline characteristics of this subgroup were similar to those of the overall population (Table S1). Compared with the overall population, 15% more participants were treated previously with a DMT in the 5-year completer population.

Outcomes

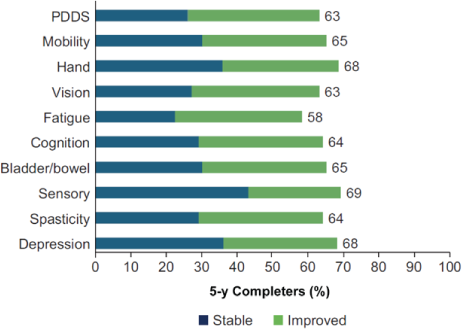

Median PDDS and PS scores for each individual domain remained stable over 5 years. The median (IQR) PDDS score was 2 (0–3) at year 0 and 2 (1–4) at year 5. Median (IQR) scores at both time points were as follows: mobility, 1 (0–3); hand, 1 (0–2); vision, 1 (0–2); fatigue, 2 (1–4); cognition, 1 (1–3); bladder/bowel, 1 (0–2); sensory, 1 (1–2); spasticity, 1 (0–2); and depression, 1 (0–2). After 5 years of DMF treatment, 58% to 69% of participants had PDDS and PS scores that either remained stable or improved across all functional domains (Figure 2).

Stable or improved Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) and Performance Scales domain scores at 5 years in 5-year completer subgroup (n = 93)

Employment Subgroup

Participants

Of the 322 participants 62 years and younger who were employed at the index date, 250 (78%) reported their employment as full-time and 72 (22%) reported their employment as part-time. At DMF initiation (index date), employed participants were younger than the overall population, with a median (IQR) age of 48 (42–54) years. Compared with the overall population, employed participants had a shorter disease and treatment duration; median (IQR) disease duration was 12 (7–16) years and DMF treatment duration was 3.5 (2.0–4.5) years (Table S1).

Employment Status and Work Productivity Outcomes

Of the participants who were employed at the index survey, 66.0% (95% CI, 57.6%–73.1%) were estimated to be free from a negative change in employment type over 5 years of DMF treatment (Figure S2). Similarly, 69.5% (95% CI, 62.8%–75.2%) were estimated to be free from needing to reduce work hours. At the time of the index survey, participants reported missing an average of 2 workdays in the past 6 months before DMF initiation. After initiating DMF treatment, the median (IQR) number of workdays missed per year was 1.0 (0.0–1.0). In the employed subgroup, 54 of 322 participants (16.8%) reported 5 or more missed workdays in any given year during the 5-year study.

Of the 294 participants who were not employed at the index survey, 109 (37.1%) had a positive change in employment status while being treated with DMF: 83 changed from unemployed to employed full-time and 26 changed from unemployed to employed part-time.

Discussion

In this cohort study, we assessed longer-term outcomes of participants treated with DMF than are routinely assessed in clinical trials. Most US NARCOMS Registry participants who were treated with DMF for up to 5 years remained free from 6-month confirmed disability (PDDS score) progression. In the ENDORSE clinical trial extension study, EDSS scores remained stable over 9 years of DMF treatment, and most participants remained free from EDSS score progression over those 9 years.5 The ENDORSE study did not collect data on whether participants converted from RRMS to SPMS.

In the present study, considering that the average MS disease duration before starting DMF treatment was 14 years, we found a low rate of conversion to SPMS over the additional 5-year DMF treatment period. Similarly, a large observational cohort study found that 10% of patients converted to SPMS, with a median time to conversion to SPMS of 32.4 years.22 The longer time to onset was likely related to use of DMTs. A large (n = 517) prospective study that followed more than 90% of patients for 10 years found that 18% of patients converted from relapsing MS to SPMS, with a median time of 16.8 years after disease onset.23 In the subgroup of participants who completed 5 years or more of DMF treatment and responded to at least one survey every year, most participants had PDDS and PS scores that either improved or remained stable.

Treatment with DMF was associated with stability or improvement across a wide range of outcomes, including PDDS scores, as well as measures of individual symptom domains such as cognition, depression, spasticity, and fatigue. Many of these domains are associated with employment status and work productivity.12,24–26 Cognitive impairment, disability, and fatigue negatively affect employment status and absenteeism.27

Symptoms of MS, most commonly fatigue, are major reasons why patients with MS leave the workforce or reduce their work hours.12,24 Employment rates across other registries range from 43% to 66%, with rates in patients with MS generally lower than those in the general population.28 Previous studies suggest that up to half of patients with MS may exit the workforce within 5 years. Most participants in the employment subgroup of the present study with an average disease duration of 12 years before starting DMF remained employed after 5 years of DMF treatment, and many also were able to maintain their baseline level of employment. In other studies, work productivity (as measured by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire–MS) also improved with DMF treatment, although most included 12 to 24 months of follow-up.3,8,9,12,14 Different DMTs have different effects on work attendance and productivity; DMF performed better or equally as well as injectable DMTs in previous studies.14,29

There are several limitations associated with this analysis, commonly noted in most analyses of registry data, including the lack of a placebo group or active comparator. Although there is no comparison arm for employment in the present study, a recent study in the NARCOMS Registry that included participants 62 years and younger irrespective of DMT use found that the percentage of patients free from a negative change in employment across 1 year was 97.7%,30 which is similar to the percentage of 94.1% (95% CI, 90.9%–96.2%) in this study. There is a lack of longer-term employment data available for comparison. The NARCOMS Registry participants are volunteers and may not fully represent the MS population. For the 5-year completer subgroup, there is the potential for bias because those who stay on DMF treatment for several years are more likely to be doing well compared with those who discontinue. However, this bias is mitigated in the analyses of the overall population because the Kaplan-Meier method uses data from all patients.

Due to the self-reported nature of the data, some of the outcomes in the present analysis may be prone to recall bias,31 as well as clinician-assessed or performance-based assessments for some outcomes, such as disability status. For example, the reported conversion to SPMS was not verified against a health care provider–confirmed diagnosis of SPMS. However, previous work suggests that persons with MS can accurately report their clinical course.32 In addition, we captured a broad range of patient-reported outcomes that are not often captured in other types of registries.

In this longitudinal assessment of outcomes in NARCOMS Registry participants treated for up to 5 years, most participants remained free from 6-month confirmed disability (PDDS score) progression and free from conversion to SPMS. Median PDDS and PS scores remained stable, and most participants had scores that either improved or remained stable across all functional domains. In addition, most NARCOMS Registry participants treated with DMF maintained their baseline level of employment and stable levels of work productivity. Among participants who were unemployed before initiating DMF, 37% became employed after starting DMF treatment. Overall, these results support the long-term efficacy profile of DMF on measures of disability and work-related outcomes.

PRACTICE POINTS

In the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry, most participants treated up to 5 years with dimethyl fumarate remained free from 6-month confirmed disability (Patient-Determined Disease Steps score) progression and conversion to secondary progressive MS.

Disability and employment status remained stable in participants treated with dimethyl fumarate.

Acknowledgments

Biogen provided funding for medical writing support in the development of this paper; Karen Spach, PhD, from Excel Scientific Solutions wrote the first draft of the manuscript based on input from authors, and Nathaniel Hoover from Excel Scientific Solutions copyedited and styled the manuscript per journal requirements. The authors thank the NARCOMS Registry participants for their participation in the Registry.

Performance Scales, Copyright Registration Number / Date: 233 TXu000743629 / 1996-04-04; assigned to DeltaQuest Foundation, Inc, effective October 1, 2005. U.S. 234 Copyright law governs terms of use.

References

Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, ; DEFINE Study Investigators. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 1098– 1107.

Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, ; CONFIRM Study Investigators. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 1087– 1097.

Kita M, Fox RJ, Gold R, Effects of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF) on health-related quality of life in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an integrated analysis of the phase 3 DEFINE and CONFIRM studies. Clin Ther. 2014; 36: 1958– 1971.

Viglietta V, Miller D, Bar-Or A, Efficacy of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: integrated analysis of the phase 3 trials. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015; 2: 103– 118.

Gold R, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, Safety and efficacy of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: 9 years’ follow-up of DEFINE, CONFIRM, and ENDORSE. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2020; 13: 1756286420915005.

Cohen JA, Trojano M, Mowry EM, Uitdehaag BM, Reingold SC, Marrie RA. Leveraging real-world data to investigate multiple sclerosis disease behavior, prognosis, and treatment. Mult Scler. 2020; 26: 23– 37.

Smoot K, Spinelli KJ, Stuchiner T, Three-year clinical outcomes of relapsing multiple sclerosis patients treated with dimethyl fumarate in a United States community health center. Mult Scler. 2018; 24: 942– 950.

Kresa-Reahl K, Repovic P, Robertson D, Okwuokenye M, Meltzer L, Mendoza JP. Effectiveness of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate on clinical and patient-reported outcomes in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis switching from glatiramer acetate: RESPOND, a prospective observational study. Clin Ther. 2018; 40: 2077– 2087.

Berger T, Brochet B, Brambilla L, Effectiveness of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate on patient-reported outcomes and clinical measures in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in a real-world clinical setting: PROTEC. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019; 5: 2055217319887191.

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008; 372: 1502– 1517.

Minden SL, Marder WD, Harrold LN, Dor L. Multiple Sclerosis: A Statistical Portrait: A Compendium of Data on Demographics, Disability, and Health Services Utilization in the United States. Abt Associates; 1993.

Glanz BI, Dégano IR, Rintell DJ, Chitnis T, Weiner HL, Healy BC. Work productivity in relapsing multiple sclerosis: associations with disability, depression, fatigue, anxiety, cognition, and health-related quality of life. Value Health. 2012; 15: 1029– 1035.

Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Samuels S, Davis M, Phillips AL, Meletiche D. The cost of disability and medically related absenteeism among employees with multiple sclerosis in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009; 27: 681– 691.

Lee A, Pike J, Edwards MR, Petrillo J, Waller J, Jones E. Quantifying the benefits of dimethyl fumarate over β interferon and glatiramer acetate therapies on work productivity outcomes in MS patients. Neurol Ther. 2017; 6: 79– 90.

PK. Average retirement age in the United States. DQYDJ. June 3, 2018. Updated November 14, 2019. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://dqydj.com/average-retirement-age-in-the-united-states

Hohol MJ, Orav EJ, Weiner HL. Disease Steps in multiple sclerosis: a simple approach to evaluate disease progression. Neurology. 1995; 45: 251– 255.

Hohol MJ, Orav EJ, Weiner HL. Disease Steps in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study comparing Disease Steps and EDSS to evaluate disease progression. Mult Scler. 1999; 5: 349– 354.

Marrie RA, Goldman M. Validity of Performance Scales for disability assessment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 1176– 1182.

Learmonth YC, Motl RW, Sandroff BM, Pula JH, Cadavid D. Validation of Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) scale scores in persons with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2013; 13: 37.

Schwartz CE, Vollmer T, Lee H; North American Research Consortium on Multiple Sclerosis Outcomes Study Group. Reliability and validity of two self-report measures of impairment and disability for MS. Neurology. 1999; 52: 63– 70.

Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Vollmer T. Validation of NARCOMS depression scale. Int J MS Care. 2008; 10: 81– 84.

Fambiatos A, Jokubaitis V, Horakova D, Risk of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Mult Scler. 2020; 26: 79– 90.

University of California SFMSET, Cree BA, Gourraud PA, Long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis disability in the treatment era. Ann Neurol. 2016; 80: 499– 510.

Simmons RD, Tribe KL, McDonald EA. Living with multiple sclerosis: longitudinal changes in employment and the importance of symptom management. J Neurol. 2010; 257: 926– 936.

Smith MM, Arnett PA. Factors related to employment status changes in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 602– 609.

Coyne KS, Boscoe AN, Currie BM, Landrian AS, Wandstrat TL. Understanding drivers of employment changes in a multiple sclerosis population. Int J MS Care. 2015; 17: 245– 252.

Salter A, Thomas N, Tyry T, Cutter G, Marrie RA. Employment and absenteeism in working-age persons with multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ. 2017; 20: 493– 502.

Salter A, Stahmann A, Ellenberger D, Data harmonization for collaborative research among MS registries: a case study in employment. Mult Scler. 2021; 27: 281– 289.

Chen J, Taylor BV, Blizzard L, Simpson S Jr, Palmer AJ, van der Mei IAF. Effects of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies on employment measures using patient-reported data. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018; 89: 1200– 1207.

Marrie RA, Leung S, Cutter GR, Fox RJ, Salter A. Comparative responsiveness of the health utilities index and the RAND-12 for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. Published online January 5, 2021. doi:1352458520981370

Schmier JK, Halpern MT. Patient recall and recall bias of health state and health status. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2004; 4: 159– 163.

Ingram G, Colley E, Ben-Shlomo Y, Validity of patient-derived disability and clinical data in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010; 16: 472– 479.