Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

A Framework of Care in Multiple Sclerosis, Part 2

Author(s):

CME/CNE Information

Activity Available Online:

To access the article, post-test, and evaluation online, go to http://www.cmscscholar.org.

Target Audience:

The target audience for this activity is physicians, physician assistants, nursing professionals, and other health-care providers involved in the management of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Learning Objectives:

Apply new information about MS to a comprehensive individualized treatment plan for patients with MS

Adjust rehabilitative interventions to accommodate for fluctuating or ongoing MS symptoms

Accreditation Statement:

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the accreditation requirements and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC), Nurse Practitioner Alternatives (NPA), and Delaware Media Group. The CMSC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

The CMSC designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Nurse Practitioner Alternatives (NPA) is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation.

NPA designates this enduring material for 1.0 Continuing Nursing Education credit.

Laurie Scudder, DNP, NP, has served as Nurse Planner for this activity. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Disclosures:

Francois Bethoux, MD, Editor in Chief of the International Journal of MS Care (IJMSC), has served as Physician Planner for this activity. He has received royalties from Springer Publishing; has received intellectual property rights from Biogen; has received consulting fees from Acorda Therapeutics, Ipsen, and Merz Pharma; and has performed contracted research for Acorda Therapeutics.

Laurie Scudder, DNP, NP, has served as Nurse Planner for this activity. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Scott D. Newsome, DO, MSCS (author), has served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Genentech, Novartis, and Genzyme and has performed contracted research (institution received funds) for Biogen, Genentech, and Novartis.

Philip J. Aliotta, MD, MSHA, CHCQM, FACS (author), has served on speakers' bureaus for Astellas Pharma, Actavis, Augmenix, and Allergan and has performed contracted research for Allergan.

Jacquelyn Bainbridge, PharmD (author), has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Susan E. Bennett, PT, DPT, EdD, NCS, MSCS (author), has served on speakers' bureaus for Acorda Therapeutics, Biogen, and Medtronic; has received consulting fees from and performed contracted research for Acorda Therapeutics; and is chair of the Clinical Events Committee at Innovative Technologies.

Gary Cutter, PhD (author), has participated on Data and Safety Monitoring Committees for AMO Pharma, Apotek, Gilead Pharmaceuticals, Horizon Pharmaceuticals, Modigenetech/Prolor, Merck, Merck/Pfizer, Opko Biologics, Neuren, Sanofi-Aventis, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Receptos/Celgene, Teva Pharmaceuticals, NHLBI (Protocol Review Committee), and NICHD (OPRU Oversight Committee); has received consulting fees from and/or served on speakers' bureaus and scientific advisory boards for Cerespir, Genzyme, Genentech, Innate Therapeutics, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Klein-Buendel Incorporated, MedImmune, Medday, Nivalis, Novartis, Opexa Therapeutics, Roche, Savara, Somahlution, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Transparency Life Sciences, and TG Therapeutics; and is President of Pythagoras, Inc., a private consulting company located in Birmingham, AL.

Kaylan Fenton, CRNP, APNP, MSCN (author), has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Fred Lublin, MD (author), has received consulting fees/fees for non-CME/CE activities from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Biogen, EMD Serono, Novartis, Teva Neuroscience, Actelion, Sanofi/Genzyme, Acorda, Questcor/Mallinckrodt, Roche/Genentech, MedImmune, Osmotica, Xenoport, Receptos/Celgene, Forward Pharma, Akros, TG Therapeutics, AbbVie, Toyama, Amgen, Medday, Atara Biotherapeutics, Polypharma, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Revalesio, Coronado Bioscience, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; has served on speakers' bureaus for Genentech/Roche and Genzyme/Sanofi; has performed contracted research for Acorda, Biogen, Novartis, Teva Neuroscience, Genzyme, Xenoport, and Receptos; is the co–chief editor of Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders; and has an ownership interest in Cognition Pharmaceuticals.

Dorothy Northrop, MSW, ACSW (author), has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

David Rintell, EdD (author), has received consulting fees from Novartis and has served as a patient education speaker for Teva Neuroscience. He started as a salaried employee of Sanofi Genzyme in November 2015. Dr. Rintell's work on this project was completed before he became a salaried employee of Sanofi Genzyme.

Bryan D. Walker, MHS, PA-C (author), has served on scientific advisory boards for EMD Serono and Sanofi Genzyme and owns stock in Biogen.

Megan Weigel, DNP, ARNP-C, MSCN (author), has received consulting fees from Mallinckrodt, Genzyme, and Genentech, and has served on speakers' bureaus for Bayer Corp, Acorda Therapeutics, Teva Neuroscience, Biogen, Mallinckrodt, Genzyme, Novartis, and Pfizer.

Kathleen Zackowski, PhD, OTR, MSCS (author), has performed contracted research for Acorda Therapeutics.

David E. Jones, MD (author), has received consulting fees from Biogen, Novartis, and Genzyme and has performed contracted research for Biogen (institution received funds).

One anonymous peer reviewer for the IJMSC has performed contracted research (institution received funds) for Novartis, Chugai, and Biogen. Another reviewer has received consulting fees and served on speakers' bureaus for Biogen, Sanofi Genzyme, Genentech, EMD Serono, and Novartis. The third reviewer has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Lori Saslow, MS (medical writer), has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The staff at the IJMSC, CMSC, NPA, and Delaware Media Group who are in a position to influence content have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Note: Disclosures listed for authors are those applicable at the time of their work on this project and within 12 months previously. Financial relationships for some authors may have changed in the interval between the time of their work on this project and publication of the article.

Funding/Support:

Funding for the Framework of Care consensus conference was provided by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, and Mylan Pharmaceuticals.

Method of Participation:

Release Date: February 1, 2017

Valid for Credit Through: February 1, 2018

In order to receive CME/CNE credit, participants must:

Review the CME/CNE information, including learning objectives and author disclosures.

Study the educational content.

Complete the post-test and evaluation, which are available at http://www.cmscscholar.org.

Statements of Credit are awarded upon successful completion of the post-test with a passing score of >70% and the evaluation.

There is no fee to participate in this activity.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use:

This CME/CNE activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not approved by the FDA. CMSC, NPA, and Delaware Media Group do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of CMSC, NPA, or Delaware Media Group.

Disclaimer:

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any medications, diagnostic procedures, or treatments discussed in this publication should not be used by clinicians or other health-care professionals without first evaluating their patients' conditions, considering possible contraindications or risks, reviewing any applicable manufacturer's product information, and comparing any therapeutic approach with the recommendations of other authorities.

Abstract

The Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) convened a Framework Taskforce composed of a multidisciplinary group of clinicians and researchers to examine and evaluate the current models of care in multiple sclerosis (MS). The methodology of this project included analysis of a needs assessment survey and an extensive literature review. The outcome of this work is a two-part continuing education series of articles. Part 1, published previously, covered the updated disease phenotypes of MS along with recommendations for the use of disease-modifying therapies. Part 2, presented herein, reviews the variety of symptoms and potential complications of MS. Mobility impairment, spasticity, pain, fatigue, bladder/bowel/sexual dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and neuropsychiatric issues are examined, and both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions are described. Because bladder and bowel symptoms substantially affect health-related quality of life, detailed information about elimination dysfunction is provided. In addition, a detailed discussion about mental health and cognitive dysfunction in people with MS is presented. Part 2 concludes with a focus on the role of rehabilitation in MS. The goal of this work is to facilitate the highest levels of independence or interdependence, function, and quality of life for people with MS.

In April 2015, the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) convened the Framework Taskforce, a multidisciplinary group of clinicians and researchers charged with investigating the current standards of care in multiple sclerosis (MS). This meeting was a follow-up of a 1993 conference sponsored by the CMSC.1 The Framework Taskforce included experts from varied fields, including neurology, biostatistics, MS nursing, pharmacy, physician assistants, rehabilitation specialists, psychology, social work, and urology. The result of the meeting is a two-part series of continuing education articles. Part 1, entitled “A Framework of Care in Multiple Sclerosis, Part 1: Updated Disease Classification and Disease-Modifying Therapy Use in Specific Circumstances,” was published in the November/December 2016 issue of the International Journal of MS Care. Part 2, presented herein, discusses MS symptoms with a particular focus on bladder and bowel dysfunction, mental health issues, and cognitive impairment, as these were identified as areas of need in a recent CMSC knowledge survey. Rehabilitation was also identified as an important topic of interest and is also addressed in this article.

The symptoms of MS vary from person to person and depend on where the central nervous system is affected. Symptoms may include fatigue, weakness, spasticity, ambulatory dysfunction, sensory symptoms, pain, cognitive impairment, emotional disorders, tremor, incoordination/ataxia, visual impairment, bladder and bowel dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, dysarthria, and dysphagia.

Some of these symptoms may be embarrassing for people with MS and providers to discuss, leading to underrecognition of these issues. A recent survey about communication, including barriers to effective communication, found that discussions about bladder/bowel/sexual dysfunction were difficult for both providers and patients, although much more so for providers. Approximately 10% of patients reported difficulty in discussing ambulatory dysfunction and cognitive dysfunction with their providers.2 Heightened awareness of these barriers to effective communication may improve recognition and treatment of these symptoms.

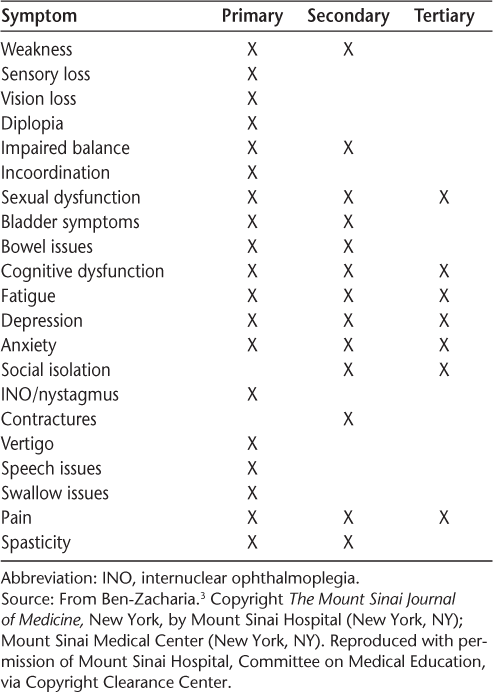

Symptoms of MS may be identified as primary, secondary, or tertiary (Table 1).3 Primary symptoms are directly related to demyelination and axonal loss; examples include vision loss and bladder dysfunction. Secondary symptoms are indirectly related to MS—for example, knee pain due to chronic genu recurvatum in a patient with a spastic monoparesis. Tertiary symptoms are the result of social and psychological effects of MS. For example, social isolation may occur as a result of depression or of bladder or bowel dysfunction.3

Primary, secondary, and tertiary symptoms in multiple sclerosis

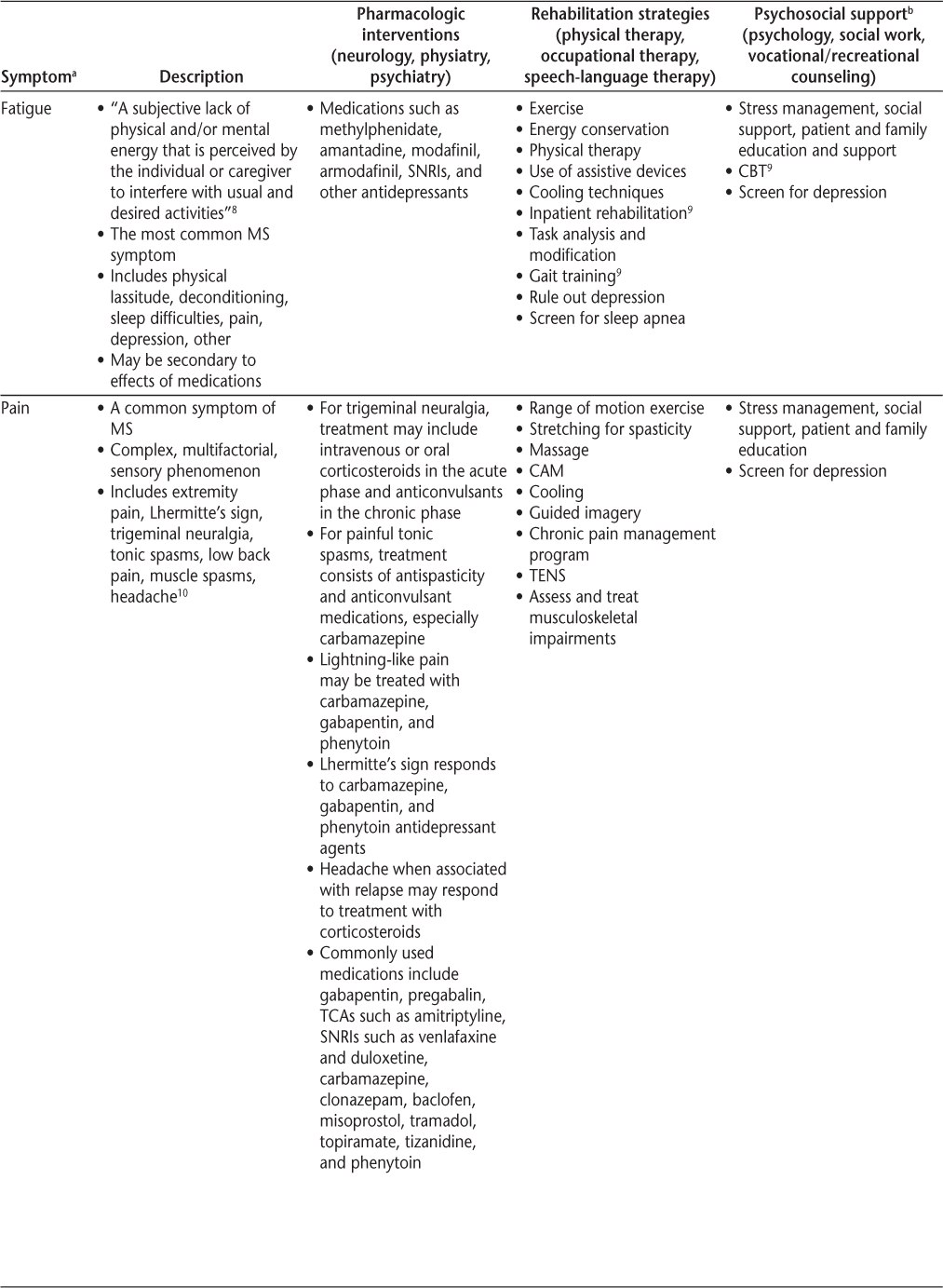

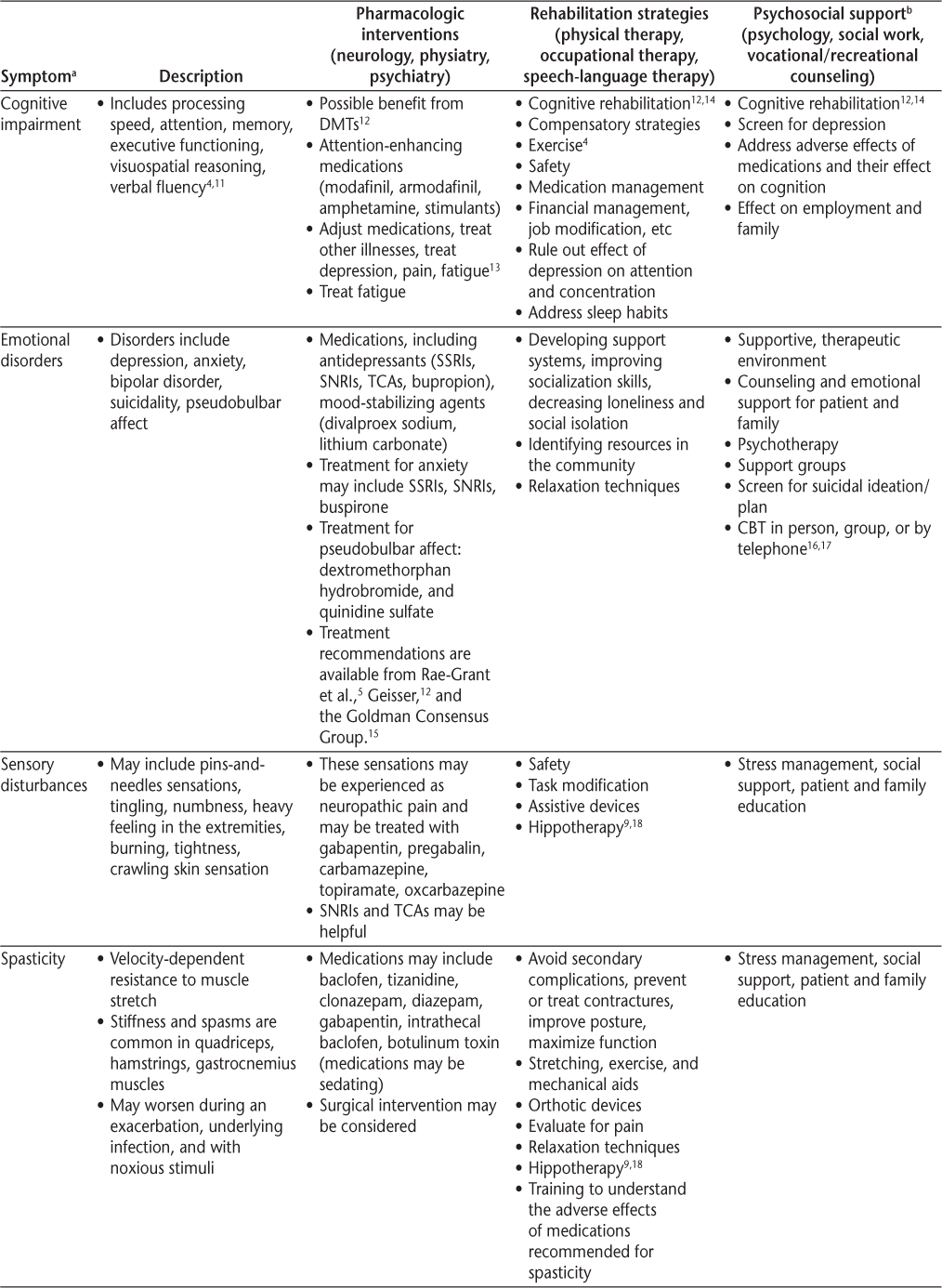

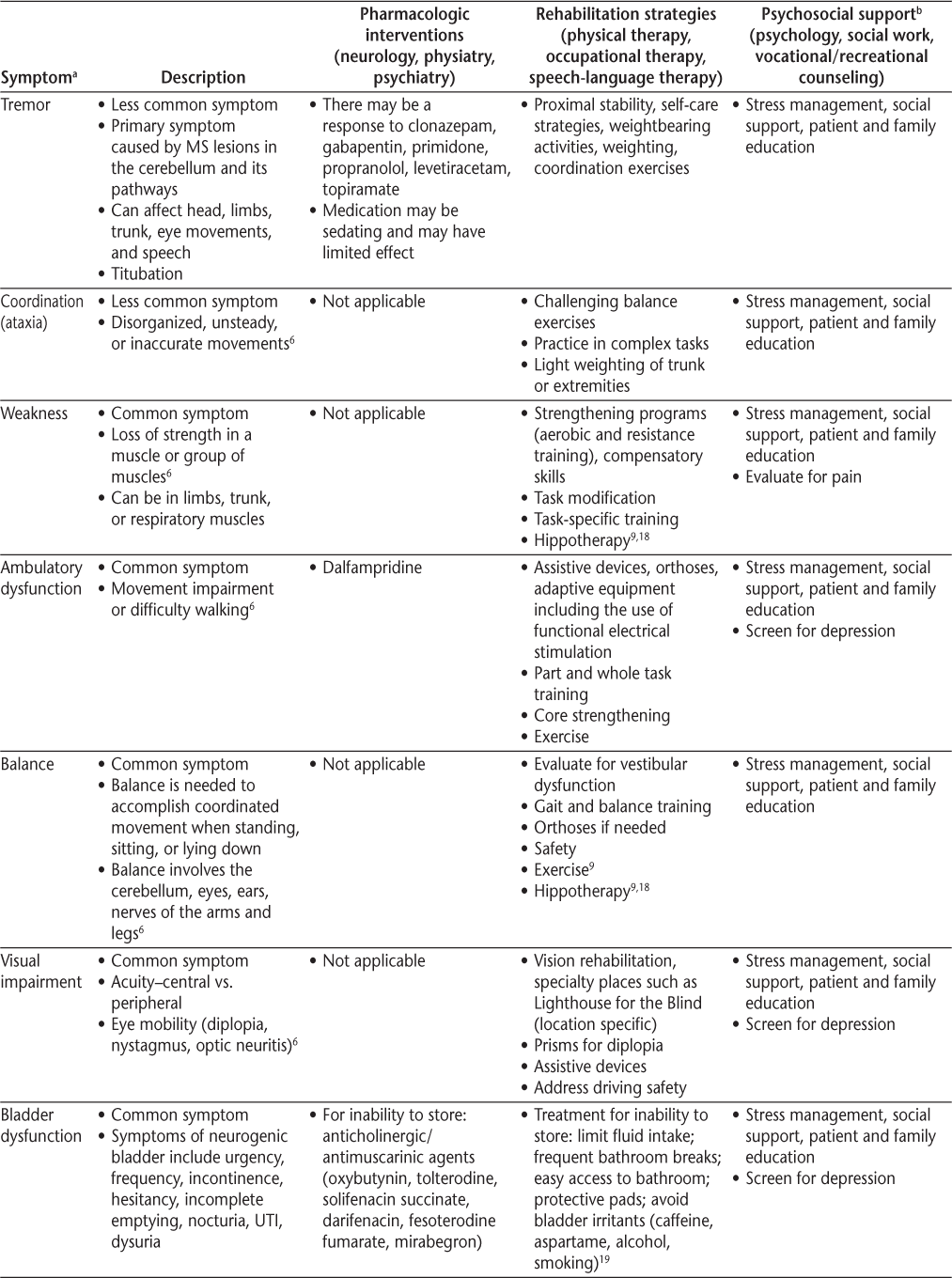

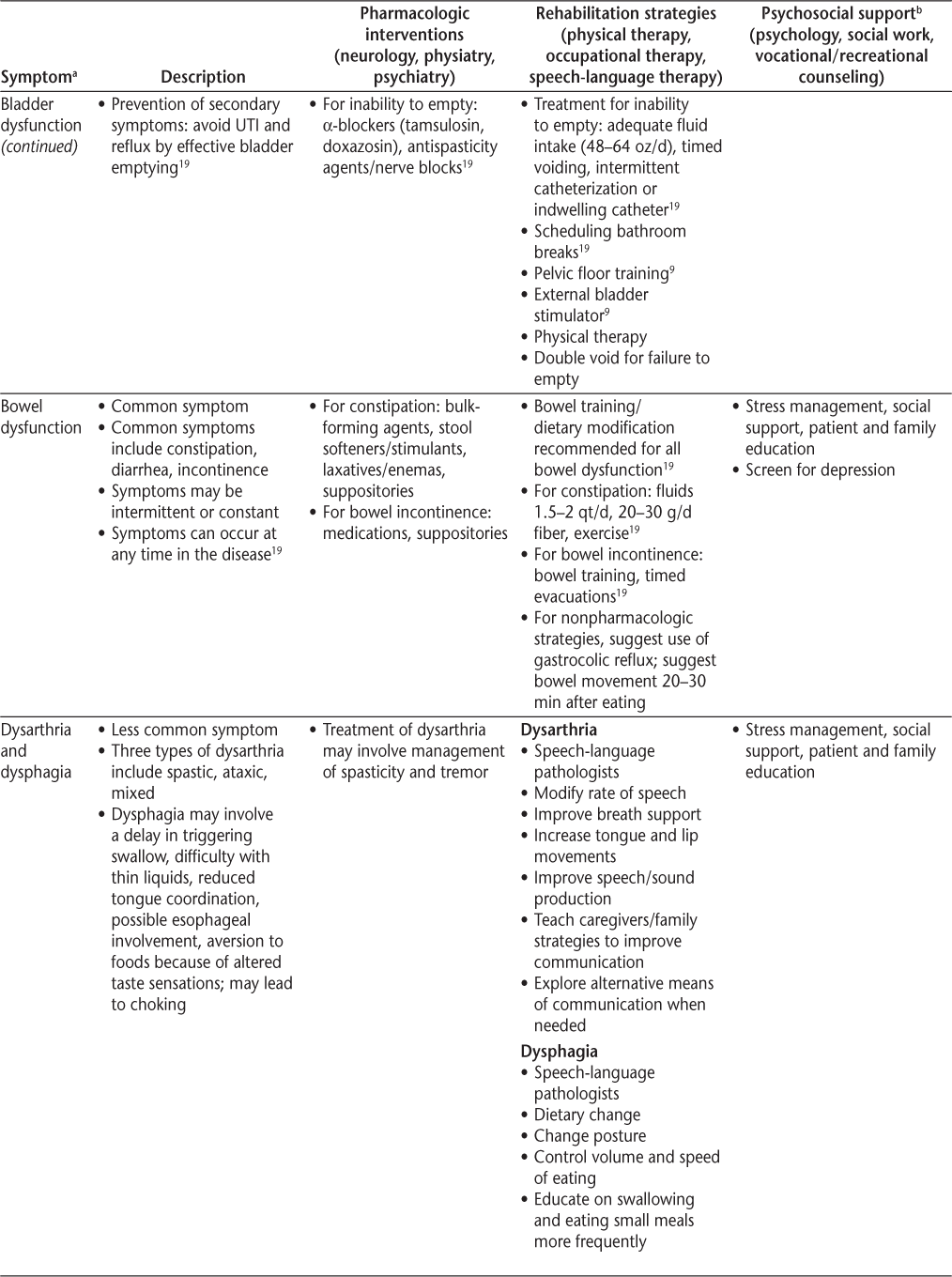

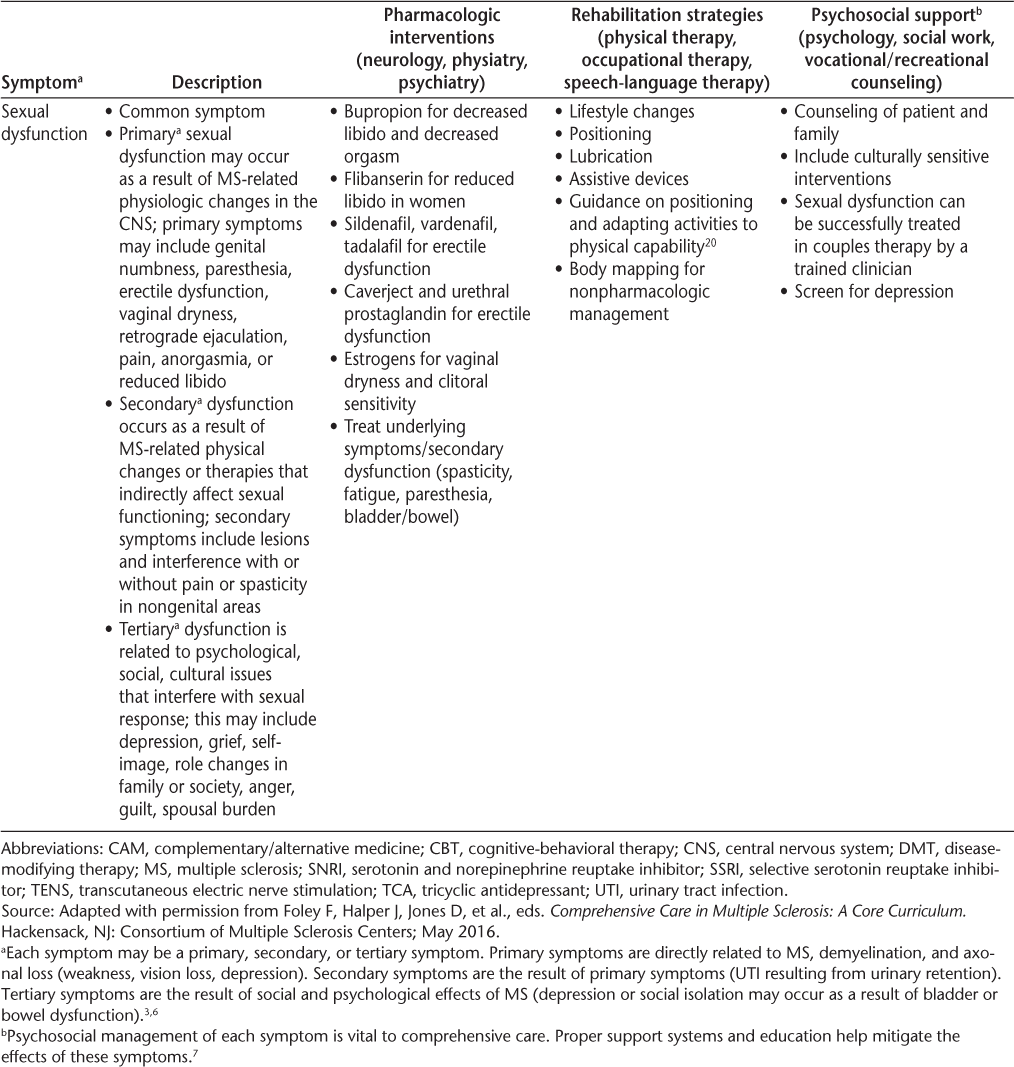

Symptomatic management is a cornerstone of comprehensive care and should use some combination of pharmacologic interventions, rehabilitation, psychosocial support, education, and counseling (Table 2). Priority should be given to symptoms that may cause substantial morbidity or mortality (depression, trauma from fall, aspiration pneumonia from dysphagia, infection from skin breakdown, or neurogenic bladder). Beyond this, it is important to help people with MS prioritize symptoms, provide individualized care, and consider the family and significant others in treatment decisions. Defining and understanding symptoms is the first step toward a goal of optimal function and improved quality of life (QOL). It is also important to consider vocational issues for people with MS and to periodically assess for wellness to allow them to achieve the best QOL possible.3 The Framework Taskforce strongly encourages referral to specialists for appropriate treatment when necessary.

Symptoms and recommended interventions for patients with multiple sclerosis3–7

Common Symptoms and Therapies

A brief description of common symptoms and suggested treatment strategies follows; further information is included in Table 2 and in the article by Bennett et al.4

Mobility/Ambulatory Dysfunction

Ambulatory dysfunction is common in people with MS, so maintaining mobility and safely maximizing independence is a primary goal for many people with MS. Fall risk should be assessed at every clinic visit, and health-care providers should clarify the etiology of the patient's altered mobility to develop an appropriate treatment plan, because abnormalities of gait can result from weakness, spasticity, imbalance, ataxia, pain, deconditioning, or orthopedic derangement. Early interventions, such as those to help maintain muscle strength and prevent joint pain, may minimize future injury and mobility limitations. Interventions may include the development of a tailored exercise program by a physical therapist, as well as the use of assistive devices and medication (dalfampridine) for ambulatory dysfunction.5

Problems related to balance can be a challenge for people with MS. Factors associated with fall risk in people with MS include dual tasking (eg, simultaneously walking and talking), impairments in sensation or vision, increased postural sway in standing, decreased trunk control, leg weakness, spasticity, and fear of falling.

Vestibular rehabilitation training has been shown to be effective in improving upright postural control and in decreasing fatigue in people with MS.21 Another study showed that a balance retraining program in individuals with mild-to-moderate MS reduced falls and improved balance; however, this program, called CoDuSe (for core stability, dual tasking, sensory strategies), did not significantly improve confidence in walking and balance. Balance confidence is a concern because people who are afraid of falling are more likely to fall.22

Research demonstrates that functional electrical stimulation can increase gait speed and improve the physiologic cost index in ambulatory people with MS.23 Functional electrical stimulation can strengthen muscles and reprogram the motor cortex, leading to a more efficient, faster pace23 24; however, the details of dose and frequency remain unclear.

Spasticity

Spasticity is defined as velocity-dependent resistance to muscle stretch, and it can be painful. Spasticity has advantages and disadvantages: it can compensate for weakness, yet it can also inhibit movement, negatively affect joints, and lead to decubitus ulcers. Treatment of spasticity should be multifaceted and may include rehabilitation (stretching, range of motion exercises), oral medications (Table 2), and localized treatment with botulinum toxin. In appropriate patients, an intrathecal baclofen pump may be helpful, and, rarely, surgical treatment (rhizotomy/myelotomy) may be warranted.5 Spasticity management recommendations are available in the publications by Rae-Grant et al.5 and Giesser.12

Pain

Pain occurs in more than half of people with MS.10 25 Primary pain is directly related to MS pathology (ie, neuropathic pain) and includes dysesthesia and paresthesia, trigeminal neuralgia, and paroxysmal cord phenomena. This pain can be treated with certain anticonvulsant or antidepressant medications; however, narcotics have a limited effect on this type of pain. Secondary MS pain can occur from musculoskeletal wear and tear, skin breakdown, and fractures from osteoporosis. Physical therapy may help prevent or reverse effects on joints, tendons, and ligaments, and anti-inflammatory and narcotic medications may offer benefit as well. Tertiary MS pain, which is a social, emotional, or cognitive response to pain, especially chronic pain, includes anxiety, fear, depression, and difficulties explaining experiences or adhering to treatment. It is important to engage mental health treatment with these aspects of pain.

Pain types are not mutually exclusive, and pain management is more than just prescribing medications. It involves enhancing support networks, encouraging behavioral changes, treatment of psychiatric comorbidities, rehabilitation therapy, exercise, and complementary/alternative treatments.

Fatigue

Fatigue affects more than 75% of patients with MS.25 It can occur early in the disease and may be the most disabling symptom of the disease. There are numerous potential confounding factors, including sleep and metabolic disorders, drug adverse effects, depression, deconditioning, and sensitivity to heat.

The work-up of fatigue should include reviewing medications, screening for depression, and assessing for anemia, metabolic derangements, thyroid dysfunction, and vitamin B12 deficiency. Nocturia and sleep disruptions from pain or shift work disorder can confound fatigue, and polysomnography to assess for sleep apnea or other parasomnia may be considered in the assessment of this symptom.

Although fatigue can be difficult to measure, the Fatigue Severity Scale and the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale can be helpful.25 Fatigue often leads to unemployment and decreased QOL. It may be compounded by increased energy expenditure due to muscle weakness and spasticity. Treatment should be multidisciplinary and includes managing comorbid conditions (including deconditioning), energy conservation (pacing, planning, and prioritizing), medications (Table 2), and possibly cognitive-behavioral therapy. Fatigue management recommendations are available in the publications by Rae-Grant et al.5 and Giesser.12

Bladder and Bowel Dysfunction

Evaluating bladder and bowel symptoms is important because bladder dysfunction has been reported in 65% to 80% of people with MS.26 The North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) registry shows that 65% of patients reported moderate-to-severe urinary symptoms. Bowel complaints are common as well, with constipation reported in 39% to 54% of patients with MS and fecal incontinence in 11% to 51%.5 19 27 Bladder and bowel symptoms may be related to each other (ie, avoiding fluid intake to remain continent can worsen constipation, which, in turn, may worsen bladder function if the full bowel puts pressure on the bladder). These symptoms result in high morbidity (social isolation, decubitus ulcers) and mortality (urosepsis) in MS. In fact, septicemia was identified as a major underlying cause of death in a recent study by Cutter et al.28 If clinicians are not asking direct and specific questions, they risk missing an important symptom that is typically treatable.

Bladder Dysfunction

It is important to understand that the cause of incontinence is not always urgency/bladder overactivity. Bladder symptoms may be explained in terms of either failure to store or failure to empty; however, checking a postvoid residual may be necessary to distinguish the two. Storage-related bladder symptoms include urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence. Other bladder-related symptoms include frequent small-volume voids during the day and evening, stress urinary incontinence, urge urinary incontinence, mixed urinary incontinence, enuresis, continuous urinary incontinence, and other situational types of urinary incontinence.29 Although patients with failure to empty may also experience urinary urgency and incontinence, they also describe hesitancy, slow or intermittent stream, splitting or spraying, and straining. Postmicturition symptoms include incomplete emptying, postmicturition dribble, and symptoms associated with sexual intercourse and pelvic organ prolapse. For complete definitions, refer to the report by Abrams et al.29

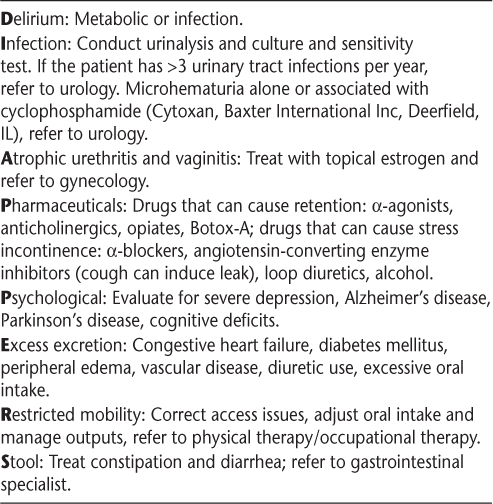

The poor specificity of clinical symptoms of MS neurogenic bladder demonstrates the frequent need for urodynamics. Urodynamic studies can detect neurogenic detrusor overactivity, detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia, increased bladder sensation, and detrusor hypocontractility. Detrusor overactivity is found in approximately 65% (range, 33%–99%) of patients with MS, and detrusor underactivity is seen in 25% (range, 0%–40%) of patients.30 31 There are many treatable causes of incontinence5 19 (Table 3) that should be considered in people with MS who experience urinary symptoms. When appropriate, early referral to a urologist for urodynamic testing is highly recommended and endorsed by the Taskforce, and gynecologic etiologies of bladder dysfunction should also be considered.

Treatable causes of incontinence (represented by the acronym DIAPPERS)

Numerous behavioral modifications for bladder symptoms include drinking moderately, focusing on no more than 4 to 6 oz per hour, and reducing or eliminating bladder irritants such as alcohol, caffeine, citrus juices, and artificial sweeteners. It is advisable to stop fluid intake 2 to 3 hours before bedtime. Timed voiding, scheduled every 2 hours while awake, may prevent bladder overfilling and reduce incontinence. Bladder retraining—teaching patients to hold urine in the bladder for an increased length of time—is also helpful. Last, Kegel exercises or pelvic floor muscle physical therapy may be recommended. Additional nonpharmacologic, lifestyle interventions are presented in the article by Namey and Halper.19

Pharmacologic treatment strategies for people with MS and bladder dysfunction may help. Medications for failure to store include anticholinergics and the newer mirabegron, a β3 agonist. Medications used to treat bladder dysfunction related to impaired bladder emptying include α-adrenergic blockers.19 32

When bladder symptoms do not improve with the previously described interventions, a urologist may consider other treatment strategies, including intermittent catheterization, onabotulinum-toxin A (Botox; Allergan, Parsippany, NJ) injections, insertion of an InterStim device (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN), percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, chronic catheterization, bladder augmentation, or urinary diversion.19 32 The urinary symptoms algorithm (Supplementary Figure 1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org)19 provides strategies and information on patient assessment and treatment. Additional information regarding treatment of urologic symptoms is available in the publications by Rae-Grant et al.5 and Adigun et al.32

Bowel Dysfunction

Bowel dysfunction is a challenging, underrecognized symptom for which our knowledge is limited. It affects approximately 60% of people with MS.26 Per NARCOMS, 39% of patients experience constipation, 11% have fecal incontinence, and 36% have both,19 33 so MS clinicians should maintain a high awareness of these symptoms in patients with MS.

The most common bowel complaint from people with MS is constipation. The World Gastroenterology Organization and the Rome Criteria19 identify constipation when patients report at least two of the following symptoms during a 12-week period: fewer than three bowel movements per week, hard stools more than 25% of the time, incomplete bowel emptying more than 25% of the time, excessive straining with bowel movements more than 25% of the time, and the need for manual disimpaction or stool manipulation.

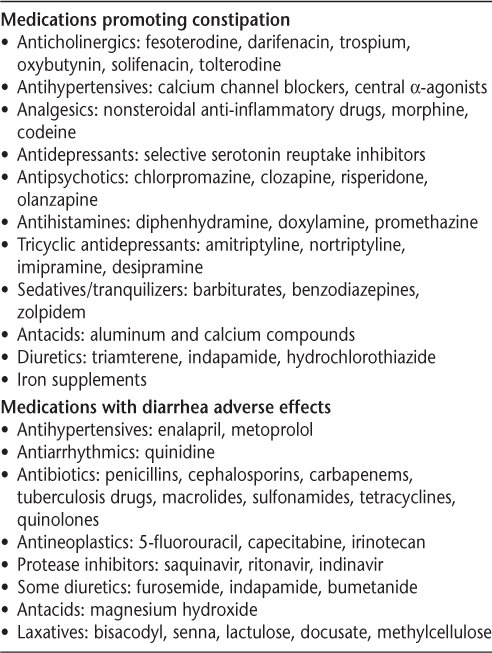

The Bowel Function Questionnaire for MS is useful to help differentiate the three types of bowel dysfunction (constipation, fecal incontinence, and mixed constipation with incontinence). Periodic assessment should include asking about stool consistency, number of bowel movements per week, straining, changes in bowel habits, painful defecation, bowel incontinence, and type of diet and activity level. It is also important to assess for secondary causes (Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis), previous surgeries (rectal, anal, and perineal), and medications that may cause constipation or diarrhea (Table 4). Evaluation should include physical examination and laboratory tests (glucose, electrolytes, calcium, and thyroid studies).

Medications that may cause constipation or diarrhea19

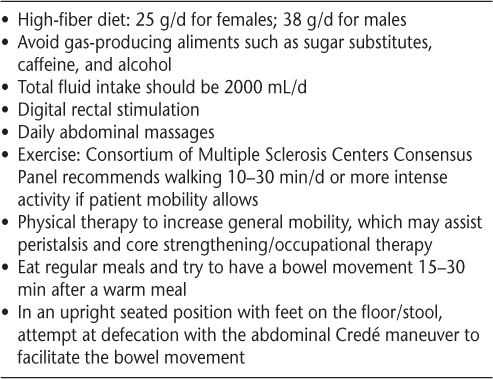

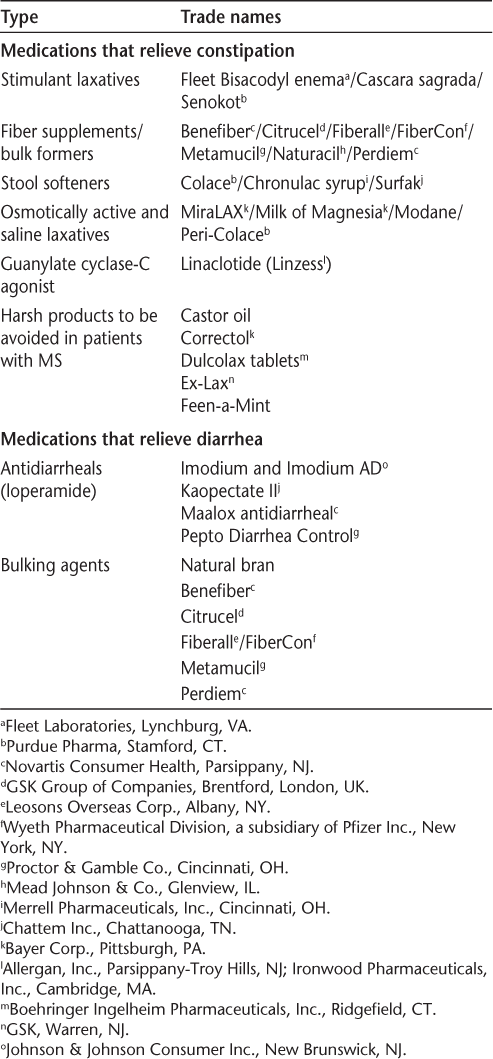

Lifestyle modifications are helpful for bowel dysfunction in people with MS (Table 5). There are various over-the-counter (OTC) medications to help relieve constipation and diarrhea (Table 6). The bowel algorithm (Supplementary Figure 2)19 provides additional information for evaluation and treatment of bowel dysfunction in people with MS. A professional needs to be involved in helping patients select appropriate OTC medications. Patients should be cautioned about overuse because electrolyte abnormalities may occur with these medications. The goal of bowel management is to establish a regular bowel evacuation schedule, which may incorporate adequate intake of food and fluids, the addition of pharmacotherapeutics (OTC or by prescription), and collaboration and planning by the patient, the family, and an MS clinician. When the goal is difficult to achieve, referral to a gastrointestinal specialist may be indicated. Management recommendations may be found in the publication by Giesser12 and in the 2012 International Journal of MS Care supplement.19

Lifestyle recommendations for treating bowel dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis

Medications that relieve constipation and diarrhea19

Mental Health and Cognition

Mental Health

In 2009, the International Journal of MS Care devoted an entire issue to depression and MS.34 For people with MS, the lifetime risk of major depressive disorder is greater than 50%, higher than that reported with other chronic neurologic illnesses.15 35 36

Unfortunately, depression remains unrecognized in many people with MS. A 2013 survey found that 60% of respondents with MS (n = 3384) reported mental health problems, but fewer than half received mental health treatment.37 38 Recognizing and treating patients with depression and other mental health disorders is important because these problems can be disabling and even fatal.

Depression is a primary determinant of QOL in MS; in fact, its effect on QOL is only slightly less than that of physical disability.39 40 The Framework Taskforce strongly recommends screening for depression for all patients with MS at every visit. Quick screening tests for depression include the Patient Health Questionnaire-2, the Beck Depression Inventory fast screen, and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Bipolar disorder is more prevalent in people with MS than in the general population. Patients with bipolar disorder exhibit periods of mania with elevated mood, inflated self-esteem, lessened need for sleep, pressured or excessive speech, and excessive pursuit of pleasurable activities. Manic episodes often alternate with periods of major depression. Suicide is an important risk for patients with bipolar disorder.41

Anxiety is also common in people with MS, three times more so than in the general population. When patients experience anxiety combined with depression, the risk of suicide increases.42 43 Depression and anxiety often coexist in MS.44 Pseudobulbar affect occurs in more than 10% of people with MS and is characterized by sudden onset of uncontrollable laughter or crying without an identifiable trigger.5 12

The rates of suicidal ideation and suicide are at least twice as high in MS as in the general population. Risk factors for suicide in MS include the presence and severity of depression, being a young male, social isolation, alcohol abuse,42 low income, progressive disease, increased disability (mobility, bowel, and bladder issues), and being early or late in the disease.28 45 Assessment of patients and referral for treatment is essential to prevent this potentially manageable cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with MS.

Mental health professionals should be among the specialists on the MS health-care team. When mental health concerns arise, referral to a mental health professional is recommended. Rintell et al.46 found that patients prefer mental health providers with knowledge about MS and experience working with patients with MS and that regular screenings and interventions should include family members when possible. A crisis hotline manned by professional counselors is available through the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (contact information: 1-800-344-4867).

Social workers engaging people with MS is another large, unmet need. Social workers can offer counseling on emotional problems, financial resources, and QOL issues, and they can provide help in locating educational resources, community programs, and other needed services. The variability and unpredictability of MS is a particular challenge for people with MS and their families. Social workers can assist with communication and support as families handle changing outcomes and responsibilities.

A variety of interventions for emotional disorders are available (Table 2). Treatment with medication requires frequent monitoring, for which referral to a mental health professional is often beneficial. When referral is not possible, patients should visit their health-care provider every 4 to 6 weeks for adjustment/maintenance of medication. Table 2 provides a list of medications and references for further information. Cognitive-behavioral therapy may be effective.16 17 It is critical for providers to screen for suicidal ideation when caring for patients with MS and to refer high-risk patients to mental health providers with knowledge about MS.

Cognition

Cognitive impairment occurs in approximately half of patients with MS (range, 43%–70%) and is the major reason people with MS leave the workplace.11 47 48 Fortunately, most people with MS have mild-to-moderate impairment, with only approximately 10% with significant cognitive impairment.49 Cognitive impairment can occur any time during the course of MS and may not correlate with physical impairment. Male sex, progressive disease, low level of education, gray matter atrophy, early age at onset of MS, and increasing age50 increase the risk of cognitive impairment in MS. Effective screening tools for cognitive dysfunction include the Symbol Digit Modalities Test and the abbreviated California Verbal Learning Test–II.47 Referral for a neuropsychological assessment should be considered when cognitive impairment is suspected, particularly if it is affecting employment or safety.

Although there are no proven pharmacologic treatments, cognitive rehabilitation by occupational therapists and speech-language pathologists (Table 2) may improve cognitive functioning in people with MS.14 Because depression can manifest as cognitive dysfunction, screening for depression and sleep disorders (and treating them when present) is important. Stimulants have also been used successfully to improve attention and reduce cognitive fatigue. Last, disease-modifying therapies may affect cognitive dysfunction over time.

Rehabilitation

The focus of rehabilitation in MS is to identify and reduce symptomatic limitations from MS to help people with MS achieve the highest possible independence, function, and QOL.9 From the time of diagnosis, rehabilitation specialists provide education and treatment designed to promote good health and general conditioning, reduce fatigue, and help people with MS feel and function their best. Comprehensive rehabilitation includes individualized patient-focused treatment plans that actively involve members of the medical team and the patient. Therapeutic exercise may enhance patient performance and abilities, and task reacquisition and environmental modification should be emphasized to improve functional ability, personal activity and participation, and QOL for people with MS.9 Other important roles for rehabilitation therapists include seating/wheelchair and driving evaluations. Later in the disease, rehabilitation should occur in a rehabilitation center whenever possible to lessen isolation and allow for more interventions to be accomplished. Rehabilitation specialists include physiatrists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, vocational counselors, and recreational therapists.

As part of the rehabilitation process, all patients should be evaluated for known symptoms associated with MS, and treatment of these symptoms should be initiated as early as possible. The benefits of rehabilitation are typically greater in the earlier phases of MS, but it can help patients in all phases of the disease.9 Rehabilitation is a valuable treatment option, and clinicians are encouraged to abandon the attitude that “nothing can be done” for patients with MS without pharmacologic treatment, especially those with advanced disease.9 There are a multitude of rehabilitation strategies for the varied symptoms of MS (Table 2). The CMSC recently published A Practical Guide to Rehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis (http://www.cmeaims.org/rehab-primer-cme.php), which provides detailed information and strategies about assessments and interventions by rehabilitation specialists. Topics covered include mobility assessments and therapeutic strategies, adaptive/assistive devices, cognitive impairment, speech/swallowing/oral health, health and wellness in MS, and complementary/alternative medicine.

Summary

Multiple sclerosis can result in a myriad of symptoms that may be overwhelming for patients and professionals. These symptoms can affect relationships, employment, and independence. Worst of all, complications from inadequately treated symptoms—such as urosepsis and suicide—can be fatal.

The Framework Taskforce put forth in this article recommendations and practical strategies for symptomatic care in MS. Understanding and defining symptoms is a critical initial step. Using pharmacologic therapies for symptomatic care is emphasized, but considering nonpharmacologic interventions is essential.

Common symptoms, including bladder and bowel dysfunction, need to be aggressively treated to help decrease potential morbidity and mortality in MS. Regarding mental health, providers should screen patients for depression, anxiety, and changes in cognition. It is essential to make mental health care available to patients and to refer to experienced specialists when possible. Treatment options may include pharmaceutical intervention, psychosocial support, psychotherapy, counseling, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and cognitive rehabilitation. The goal is to improve QOL for all those affected by MS.

PracticePoints

It is important for health-care professionals to be aware of the varied symptoms and complications of MS, including trauma due to falls, chronic urinary dysfunction, skin complications, major depressive disorder, gastrointestinal disorders, dysphagia, pulmonary dysfunction, and sepsis. When appropriate, health-care providers are strongly encouraged to refer patients to specialists for treatment.

Multidisciplinary care is essential for effective management of many MS symptoms, including bowel and bladder dysfunction, especially since these symptoms are often overlooked or inadequately treated.

Health-care clinicians must maintain a keen awareness of mental health issues that affect people with MS, including depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety. The rates of suicide and suicidal ideation are at least twice as high as in the general population.

Rehabilitation and sustaining mobility and fitness are important aspects of facilitating a healthful lifestyle.

Acknowledgments

This continuing medical education article is based on information from the Framework of Care consensus conference, which was organized as a special project by the CMSC. We thank Lori Saslow (Great Neck, NY), a medical writing consultant on behalf of the CMSC, for her assistance with manuscript development, preparation, and editing. Ms. Saslow's work was funded by the CMSC.

References

Halper J, Burks JS. Care patterns in multiple sclerosis: principal care, comprehensive team care, consortium care. NeuroRehabilitation. 1994; 4:67–75.

Tintore M, Duddy M, Jones DE, et al. The state of MS: current insight into patient-neurologist relationships, barriers to communication, and treatment satisfaction. Poster presented at: Joint ACTRIMS-ECTRIMS meeting; September 10–13, 2014; Boston, MA.

Ben-Zacharia AB. Therapeutics for multiple sclerosis symptoms. Mt Sinai J Med N Y. 2011; 78:176–191.

Bennett SE, Bethoux F, Brown TR, et al. Complex symptoms and mobility in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2014;16(suppl 1):1–40.

Rae-Grant A, Fox R, Bethoux F, eds.Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders: Clinical Guide to Diagnosis, Medical Management, and Rehabilitation. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2013.

Schapiro RT. Managing the Symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis. 6th ed. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

Psychosocial support. National Multiple Sclerosis Society website. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Managing-MS/Psychosocial-Support. Published 2015. Accessed May 11, 2015.

National Clinical Advisory Board of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Management of MS-related fatigue. http://www.nationalms-society.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/Opinion-Paper-Management-of-MS-Related-Fatigue.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed May 11, 2015.

Beer S, Khan F, Kesselring J. Rehabilitation interventions in multiple sclerosis: an overview. J Neurol. 2012; 259:1994–2008.

O'Connor AB, Schwid SR, Herrmann DN, Markman JD, Dworkin RH. Pain associated with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and proposed classification. Pain. 2008; 137:96–111.

Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis, I: frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology. 1991; 41:685–691.

Giesser BS, ed. Primer on Multiple Sclerosis. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Wilken JA, Sullivan C, Wallin M, et al. Treatment of multiple sclerosis–related cognitive problems with adjunctive modafinil: rationale and preliminary supportive data. Int J MS Care. 2008; 10:1–10.

Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. The influence of cognitive dysfunction on benefit from learning and memory rehabilitation in MS: a sub-analysis of the MEMREHAB trial. Mult Scler J. 2015; 21:1575–1582.

Goldman Consensus Group. The Goldman Consensus statement on depression in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11:328–337.

Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Goodkin DE, Bostrom A, Epstein L. Comparative outcomes for individual cognitive-behavior therapy, supportive-expressive group psychotherapy, and sertraline for the treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001; 69: 942–949.

Mohr DC, Hart S, Vella L. Reduction in disability in a randomized controlled trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy. Health Psychol. 2007; 26:554–563.

Lindroth JL, Sullivan JL, Silkwood-Sherer D. Does hippotherapy effect use of sensory information for balance in people with multiple sclerosis? Physiother Theory Pract. 2015; 31:575–581.

Namey M, Halper J. Elimination dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2012;14(suppl 1):1–26.

Darija K-T, Tatjana P, Goran T, et al. Sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: a 6-year follow-up study. J Neurol Sci. 2015; 358:317–323.

Hebert JR, Corboy JR, Manago MM, Schenkman M. Effects of vestibular rehabilitation on multiple sclerosis-related fatigue and upright postural control: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2011; 91:1166–1183.

Nilsagård YE, von Koch LK, Nilsson M, Forsberg AS. Balance exercise program reduced falls in people with multiple sclerosis: a single-group, pretest-posttest trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014; 95:2428–2434.

Paul L, Rafferty D, Young S, Miller L, Mattison P, McFadyen A. The effect of functional electrical stimulation on the physiological cost of gait in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008; 14:954–961.

Everaert DG, Thompson AK, Chong SL, Stein RB. Does functional electrical stimulation for foot drop strengthen corticospinal connections? Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010; 24:168–177.

Bennett SE, Bethoux F, Finlayson M, Heyman R. Subjective symptoms breakout group discussion. Int J MS Care. 2014;16(suppl 1):25–32.

Bennett SE, Bethoux F, Weinstock-Guttman B. Comorbidities breakout group discussion. Int J MS Care. 2014;16(suppl 1):19–24.

Bladder problems. National Multiple Sclerosis Society website. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis/MS-Symptoms/Bladder-Dysfunction. Published 2015. Accessed December 3, 2015.

Cutter GR, Zimmerman J, Salter AR, et al. Causes of death among persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015; 4:484–490.

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002; 21:167–178.

De Sèze M, Ruffion A, Denys P, Joseph P-A, Perrouin-Verbe B; GENULF. The neurogenic bladder in multiple sclerosis: review of the literature and proposal of management guidelines. Mult Scler. 2007; 13:915–928.

Ciancio SJ, Mutchnik SE, Rivera VM, Boone TB. Urodynamic pattern changes in multiple sclerosis. Urology. 2001; 57:239–245.

Adigun M, Adesoye A, Ayoola A, Lteif L, Amaechi O. Review of nonneurogenic overactive bladder. http://www.uspharmacist.com/continuing_education/ceviewtest/lessonid/110329. Published August 1, 2014. Accessed October 28, 2015.

Gulick E. Comparison of prevalence related medical history, symptoms, and interventions regarding bowel dysfunction in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010; 42:E12–E23.

Stone LA. Editorial. Int J MS Care. 2009;11:vi.

Schiffer RB. Depression and multiple sclerosis: an immunomodulatory connection? Int J MS Care. 2009; 11:149–153.

Majmudar S, Schiffer RB. Why depression goes unrecognized in multiple sclerosis patients. Int J MS Care. 2009; 11:154–159.

Minden SL, Ding L, Cleary PD, et al. Improving the quality of mental health care in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2013; 335:42–47.

Garcia J, Finlayson M. Mental health and mental health service use among people aged 45+ with multiple sclerosis. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2005; 24:9–22.

D'Alisa S, Miscio G, Baudo S, Simone A, Tesio L, Mauro A. Depression is the main determinant of quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a classification-regression (CART) study. Disabil Rehabil. 2006; 28: 307–314.

Berrigan LI, Fisk JD, Patten SB, et al. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: direct and indirect effects of comorbidity [published online ahead of print March 9, 2016]. Neurology. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002564.

Rintell DJ. Depression and other psychosocial issues in multiple sclerosis. In: Weiner HL, Stankiewicz J, eds. Multiple Sclerosis Diagnosis and Therapy. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012:263–282.

Feinstein A. An examination of suicidal intent in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2002; 59:674–678.

Feinstein A, Magalhaes S, Richard J-F, Audet B, Moore C. The link between multiple sclerosis and depression. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014; 10:507–517.

Jones KH, Jones PA, Middleton RM, et al. Physical disability, anxiety and depression in people with MS: an internet-based survey via the UK MS Register. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104604.

Turner AP, Williams RM, Bowen JD, Kivlahan DR, Haselkorn JK. Suicidal ideation in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006; 87:1073–1078.

Rintell DJ, Frankel D, Minden SL, Glanz BI. Patients' perspectives on quality of mental health care for people with MS. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012; 34:604–610.

Foley FW, Bennett SE, Bethoux F. Cognition breakout group discussion. Int J MS Care. 2014;16(suppl 1):33–36.

Foley FW, Benedict RHB, Gromisch ES, DeLuca J. The need for screening, assessment, and treatment for cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: results of a multidisciplinary CMSC consensus conference, September 24, 2010. Int J MS Care. 2012; 14:58–64.

Cognitive changes. National Multiple Sclerosis Society website. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis/MS-Symptoms/Cognitive-Changes. Accessed November 3, 2015.

Savettieri G, Messina D, Andreoli V, et al. Gender-related effect of clinical and genetic variables on cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2004; 251:1208–1214.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Newsome has served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Genentech, Novartis, and Genzyme and has performed contracted research (institution received funds) for Biogen, Genentech, and Novartis. Dr. Aliotta has served on speakers' bureaus for Astellas Pharma, Actavis, Augmenix, and Allergan and has performed contracted research for Allergan. Dr. Bainbridge has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bennett has served on speakers' bureaus for Acorda Therapeutics, Biogen, and Medtronic; has received consulting fees from and performed contracted research for Acorda Therapeutics; and is chair of the Clinical Events Committee at Innovative Technologies. Dr. Cutter has participated on Data and Safety Monitoring Committees for AMO Pharma, Apotek, Gilead Pharmaceuticals, Horizon Pharmaceuticals, Modigenetech/Prolor, Merck, Merck/Pfizer, Opko Biologics, Neuren, Sanofi-Aventis, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Receptos/Celgene, Teva Pharmaceuticals, NHLBI (Protocol Review Committee), and NICHD (OPRU Oversight Committee); has received consulting fees from and/or served on speakers' bureaus and scientific advisory boards for Cerespir, Genzyme, Genentech, Innate Therapeutics, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Klein-Buendel Incorporated, MedImmune, Medday, Nivalis, Novartis, Opexa Therapeutics, Roche, Savara, Somahlution, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Transparency Life Sciences, and TG Therapeutics; and is President of Pythagoras, Inc., a private consulting company located in Birmingham, AL. Ms. Fenton has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Lublin has received consulting fees/fees for non-CME/CE activities from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Biogen, EMD Serono, Novartis, Teva Neuroscience, Actelion, Sanofi/Genzyme, Acorda, Questcor/Mallinckrodt, Roche/Genentech, MedImmune, Osmotica, Xenoport, Receptos/Celgene, Forward Pharma, Akros, TG Therapeutics, AbbVie, Toyama, Amgen, Medday, Atara Biotherapeutics, Polypharma, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Revalesio, Coronado Bioscience, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; has served on speakers' bureaus for Genentech/Roche and Genzyme/Sanofi; has performed contracted research for Acorda, Biogen, Novartis, Teva Neuroscience, Genzyme, Xenoport, and Receptos; is the co–chief editor of Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders; and has an ownership interest in Cognition Pharmaceuticals. Ms. Northrop has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rintell has received consulting fees from Novartis and has served as a patient education speaker for Teva Neuroscience. He started as a salaried employee of Sanofi Genzyme in November 2015. Dr. Rintell's work on this project was completed before he became a salaried employee of Sanofi Genzyme. Mr. Walker has served on scientific advisory boards for EMD Serono and Sanofi Genzyme and owns stock in Biogen. Dr. Weigel has received consulting fees from Mallinckrodt, Genzyme, and Genentech, and has served on speakers' bureaus for Bayer Corp, Acorda Therapeutics, Teva Neuroscience, Biogen, Mallinckrodt, Genzyme, Novartis, and Pfizer. Dr. Zackowski has performed contracted research for Acorda Therapeutics. Dr. Jones has received consulting fees from Biogen, Novartis, and Genzyme and has performed contracted research for Biogen (institution received funds).

Funding/Support: Funding for the Framework of Care consensus conference was provided by the CMSC, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, and Mylan Pharmaceuticals.