Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Self-Management for People with Multiple Sclerosis

People with multiple sclerosis (MS) must manage the day-to-day effects of the disease on their lives. Self-management interventions may be helpful in this challenge. An international, multidisciplinary consensus conference was held on November 15, 2010, by the University of Washington's Rehabilitation Research and Training Center for Multiple Sclerosis (MS RRTC), with funding from the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), to discuss the concept of self-management for people with MS. The specific goals of the consensus conference were as follows: 1) review the current research on self-management and related issues in chronic disability and specifically in MS; 2) review optimal research methodologies, outcome measurement tools, program planning frameworks, and dissemination strategies for self-management research; and 3) establish recommendations on the next steps necessary to develop, adapt, and test self-management interventions for people with MS. The consensus conference and this document are the initial steps toward achieving the stated goals. Participants in the consensus conference concluded that it is necessary to: 1) define an empirically based conceptual model of self-management for people with MS; 2) establish reliable and valid self-management outcome measures; 3) use best practices to validate models of self-management interventions; and 4) plan dissemination and knowledge translation of interventions once their effectiveness is established.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, often disabling condition involving the central nervous system that currently affects an estimated 400,000 people in the United States.1 A diagnosis of MS is typically given in the prime of life, between the ages of 20 and 50 years. The disease is two to three times more common in women than in men and is most prevalent in whites.1 2 Although MS is characterized by a wide variety of symptoms, changes in cognition and limitations in mobility are the most significant ones associated with disability.3 4 Other common symptoms that may not be readily apparent to outside observers but are nonetheless impairing include fatigue,5–7 chronic pain,8 depression,9–12 and sleep disturbance.13–16 Self-management is a potential approach to mitigating the symptoms associated with MS.

Because of the paucity of evidence supporting the use of self-management interventions in MS, funding was sought and secured from the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) to convene a consensus conference. The Consensus Conference on Self-Management and MS was held on November 15, 2010, in Washington, DC. Participating in the conference were 50 self-management experts from the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada—including physicians, rehabilitation researchers, nurses, occupational therapists, and psychologists specializing in MS—as well as leaders from prominent nonprofit organizations supporting people with MS and representatives of federal agencies. The specific goals of the consensus conference were as follows: 1) review the current research on self-management in diverse chronic disabilities as well as MS; 2) review optimal research methodologies, outcome measurement tools, program planning frameworks, and dissemination strategies for self-management research; and 3) establish recommendations on the next steps necessary to develop, adapt, and test self-management interventions for people with MS. The conference began with informational review presentations by experts in the field of self-management and concluded with breakout sessions in which work group discussions covered the following self-management topics: 1) intervention techniques and delivery methods, 2) impact measurement, 3) appropriate research methodologies, and 4) translation to consumers.

Self-Management: What Can We Learn from Other Chronic Conditions?

Self-management has been described within the chronic care model,17 18 which includes self-management support as a way for physicians and other health-care providers to empower and prepare patients to manage their own health and health care. The concept of self-management has developed over the last 40 years and undergone various definitions, adaptations, and formulations.19–21 The central tenet in self-management is that the day-to-day oversight of the chronic condition is managed by the individuals living with the condition, rather than their health-care providers.22 In other words, the overall goal of self-management is to help people help themselves, with the premise that the better their self-management, the better their symptom control and quality of life. However, the focus in this work is on actual patient self-management activity rather than a health-systems intervention or basic patient education.21

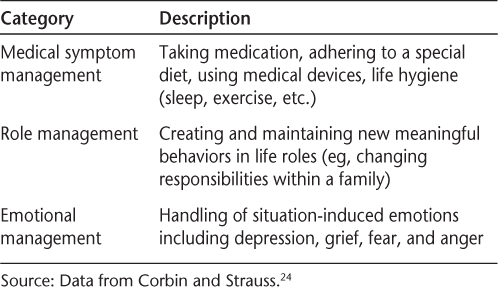

Much of the early research on self-management was performed in the area of arthritis by Lorig and colleagues at the Stanford Patient Education Research Center (http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/).22 23 The primary tasks typically taught in Lorig and colleagues' 2004 conceptualization of self-management are managing medical symptoms, roles, and emotions (Table 1).24 25 Some of the core self-management skills in this model are problem-solving, decision making, resource utilization, forming partnerships with health-care providers, and taking action.22

Self-management tasks

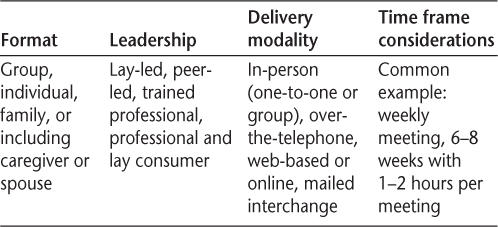

Self-management interventions have been developed for and tested in a variety of other chronic conditions, including diabetes,26 heart disease,27 hypertension,28 cancer,29 and limb loss.30 Self-management formats, delivery modalities, and session structure and length have evolved to encompass a variety of techniques. Elements of the types of programs that are commonly used are described in Table 2. In addition to promoting skills for managing disease-specific symptoms, self-management approaches may also address skills for promoting overall health and psychological well-being.31 It should be emphasized that the template of offerings in Table 2 is simply what is generally offered and is chiefly “professionally driven,” not necessarily evidence-based or reflecting consumer input.

Self-management intervention structure

Self-Management: The Case of MS

The self-management literature with regard to MS is limited.32 33 Observational and qualitative research has examined self-management in MS. Using a multidimensional instrument designed to evaluate self-management behavior among people with MS,34 researchers demonstrated that self-management is strongly associated with perceived control and that both perceived control and self-management mediate the relationships between the physical and emotional impact of MS and quality of life.35 In one qualitative study,36 participants with MS described the need for self-management support that recognizes the complex constellation of symptoms they manage and that is individualized to enhance their ability to manage not only their particular symptoms but also the impact of symptoms in the context of their preferences and values.

The few studies of self-management interventions that exist suggest that the approach holds promise for people living with MS. Stuifbergen et al.37 reported on an eight-session wellness intervention for women with MS that was chiefly focused on health and physical functioning, with sessions also dealing with stress management and relationship/intimacy. Multiple outcome measures indicated that participants realized significant improvements in self-efficacy, health behaviors, and certain quality of life dimensions. Bombardier et al.38 conducted a randomized controlled trial of a six-session (one in-person, five telephone) intervention for health promotion in people with MS. Although not labeled “self-management,” the motivational interviewing–based intervention incorporated many self-management elements, including goal-setting, self-monitoring, enhancing self-efficacy, problem-solving, and emphasis on the individual's responsibility to change health behaviors. Bombardier et al. reported that individuals who participated in the intervention showed increases in health-promotion activities, including physical activity, stress management, and spiritual growth.

Although they did not categorize their interventions as “self-management,” Mohr and colleagues39 40 have shown the benefits of telephone-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy in reducing depression; they are also completing research on the benefits of cognitive-behavioral programs in stress management (DC Mohr, personal communication, November 2011). A few other MS self-management programs have targeted specific areas such as fatigue or energy conservation,41 medication adherence,42 and consumer physical conditioning sessions (provided by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society or the Multiple Sclerosis Foundation) at various sites. One methodologically strong randomized controlled trial41 reported that a 6-week MS fatigue management program, which included self-management skills training, was efficacious in reducing fatigue impact relative to a wait-list control group. The fatigue management intervention was delivered by teleconference calls to small groups of individuals with MS, suggesting that, as found by Mohr et al.,39 40 telehealth self-management interventions have potential for overcoming access barriers in MS.

Setting the Stage for MS Self-Management Considerations

The conference consisted of three phases: 1) the first half of the day focused on presentations by self-management experts; 2) the second phase involved work group breakout sessions; and 3) the third phase brought all participants together to discuss and summarize the work group recommendations. Following are brief highlights of the expert presentations.

Delivering Effective Self-Management Interventions—Stephen Wegener, PhD, ABPP

Dr. Wegener described how the current health-care environment—including increased emphasis on patient-centered care, chronic care models, and greater responsibility placed on consumers to manage their health—is conducive to self-management intervention development, evaluation, and implementation. He pointed out that self-management is both a philosophy of care and a set of tools for responding to the challenges of managing chronic conditions. He reviewed four key elements of self-management interventions across studies: knowledge of the condition, self-monitoring, problem-solving, and skill acquisition. Common self-management targets include emotional and behavioral management skills and self-efficacy. After this overview, he described the typical format for self-management interventions, consisting of six to eight group sessions led by a disability professional and/or trained lay leader. Within the self-management field, the use of other delivery methods and formats is growing. Evaluation of such approaches is needed. Dr. Wegener summarized the evidence base for self-management, noting that the strength of the evidence varies among conditions, populations, and the outcomes chosen. He discussed a participatory action research (PAR)–driven self-management intervention for individuals with limb loss30 and noted the benefits of a PAR approach to developing, testing, and sustaining self-management interventions. In conclusion, he emphasized the need for attention to dissemination, diffusion, and sustainability relating to self-management programs.

Self-Management in Chronic Disability: An International Perspective—Susan Mills, PhD

Dr. Mills described the difficulties experienced by an international group of chronic care researchers in coming to agreement on definition of terms in chronic disability self-management. She emphasized the importance of a shared vision and research framework for national and international collaborative efforts. Of special interest was Dr. Mills's emphasis on the consideration of social determinants in self-management research (eg, income level, race, and educational level); moreover, she stressed that self-management interventions need to be agreed upon by all parties, disease-specific, and integrated into primary-care health services. Finally, she explained that self-management should be viewed as a shared responsibility, with organizational structures in place to support the individual in implementing self-management interventions.

New Tools and New Methods in Measurement—Dagmar Amtmann, PhD

Dr. Amtmann's presentation emphasized the importance of using sound measurement tools and provided an overview of new measurement initiatives being developed and funded by the University of Washington's Rehabilitation Research and Training Center for Multiple Sclerosis (MS RRTC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Successful self-management research necessitates brief, easy-to-administer, and precise instruments to measure outcomes for research and clinical practice. Secondary conditions in MS require psychometrically sound measurement instruments because of the variable nature of MS and the tendency for secondary conditions to be confused with other symptomatology. For instance, measures of depression often include questions about fatigue and sleep disturbance, which could be more attributable to the primary MS disability rather than to depression. In response to the deficit of accurate measurement tools, the NIH funded three new national measurement initiatives: PROMIS43 and NeuroQoL,44 which use item pools for the development and administration of patient-reported outcomes (PROs); and the NIH Toolbox,45 which incorporates objective measures as well as PROs. The MS RRTC has developed a Self-Efficacy Scale for Disease Management (SESDM)46 as well as a Physical Function for Mobility Aid Users,47 both of which have been validated in people with MS.

Chronic Disability Self-Management and Self-Management Support: A Public Health Perspective—Teresa Brady, PhD

Dr. Brady began her presentation by describing self-management as one of the intersections between public health and clinical care. She described the roles of self-management and self-management support within the chronic care model. She emphasized the difficulty of translating evidence-based research into the everyday public health process and used the arthritis program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a positive example. Dr. Brady underscored the need to bridge the gap between researchers and practitioners not currently using evidence-based intervention models. She discussed the RE-AIM framework (www.reaim.org) as a model of estimating the translatability and public health impact of an intervention; this model may be useful in bridging the translation gap. In summary, Dr. Brady emphasized the need to move workable interventions on to dissemination in a cost-sustainable manner.

Ethics in Self-Management—Barbara Redman, PhD

Dr. Redman also endorsed the need for a self-management emphasis in MS, focusing more on patient capabilities and positive functioning rather than basic medical treatment adherence. She also recommended increased support for the role of the MS nurse specialist in MS self-management intervention. Much of Dr. Redman's presentation, however, captured an ethics perspective. She expressed strong concerns about quality maintenance and long-term sustentation of self-management programs, mostly with regard to continued funding. She stressed the importance of evaluating both the positive and negative effects on the family and caregiver systems. With the patient undergoing role and activity changes due to involvement in self-management programs, are we taking into account the impact on significant others? She believes that this perspective is generally overlooked.

The Status of Self-Management in Epilepsy: The Managing Epilepsy Well Network and a Consumer-Generated Self-Management Intervention—Robert Fraser, PhD, CRC, and Erica Johnson, PhD, CRC

This presentation was given in two parts. First was an overview of the national Managing Epilepsy Well (MEW) self-management research network, which was followed by a specific description of the University of Washington consumer-generated (survey-based) self-management intervention for adults with epilepsy. The MEW research network involves different self-management research projects in epilepsy across four US universities, with activities coordinated by Emory University. All projects are funded by the CDC, but the universities collaborate on research projects other than their own and on the development of measurement tools, training, dissemination strategies, and so on. This is a prime example of research growth in disability self-management as a function of well-targeted funding and collaboration among grant recipients. The University of Washington self-management study is of interest because it is one of the few examples of extensive consumer response (61%) via survey regarding self-management intervention content and delivery modality preferences. The survey response indicated that the salient domains of needs were rated much higher for those with significant depression or cognition problems, emphasizing the importance of considering subgroup needs.

Unique Concerns and Efforts in Multiple Sclerosis—Dawn Ehde, PhD

Dr. Ehde's presentation summarized the existing evidence for self-management interventions in MS based on a recent review conducted by several of our conference participants.33 Rae-Grant et al. classified the evidence for self-management in neurologic disorders, including MS, using the American Academy of Neurology criteria and identified only one Class I study and one Class III study supporting a self-management approach in MS. The review concluded that self-management is relevant to MS and warrants more high-quality research. Dr. Ehde then briefly described three self-management intervention research projects currently under way that use telehealth delivery: two for fatigue in MS (Finlayson et al.41; A Turner, personal communication, May 2010) and one for fatigue, pain, and/or mood (Wazenkewitz and Ehde48). Dr. Ehde presented survey data on barriers reported by people with MS to accessing pain self-management services as an example of potential challenges to developing and delivering self-management interventions in MS. She hypothesized that the current emphasis on telehealth applications of self-management in MS may reflect attempts to address the barriers many of those with MS may encounter, such as distance from health-care facilities, transportation difficulties, and financial limitations.

Gaps in MS Self-Management Research

The perspectives of the conference participants regarding the current state of self-management research—and, in particular, self-management efforts in MS—are reflected by the following concerns:

1) Although a few self-management interventions have empirical support for their use in managing fatigue41 and promoting health,37 49 most MS self-management programs currently offered to consumers are not based on evidence of their efficacy in MS.

2) Little is known about the effective ingredients of self-management programs in MS. Interventions in MS often focus on education rather than problem-solving, skill-building, and other components established in other disability self-management research. The relative efficacy of these different intervention components is not known.

3) In MS self-management, little is known about the efficacy of different intervention delivery methods (eg, in-person, individual, group, telehealth).

4) Research does not address the constellation of secondary symptoms in MS (eg, fatigue, pain, depression) or focuses on only one of these symptoms. Although a focus on individual symptoms is also important, there is a gap in our knowledge of how self-management interventions may address the constellation of symptoms or be individualized to a given patient situation.

5) Self-management programs vary widely in terms of focus and delivery strategy, as do the measures used to evaluate outcomes. Consistent outcome measures across studies are necessary to allow effective comparison. In addition, collecting data on more global outcomes, such as number of hospitalizations, health-care utilization, and health-care costs, would be useful to facilitate potential policy changes and adoption of self-management programs in a clinical setting.50

6) In addition to the paucity and limitations of MS self-management research, there has been little effort to consider dissemination, knowledge translation, and sustainability of programming.

7) Although PAR has been beneficial to designing, evaluating, and translating self-management interventions in at least one other chronic condition, limb loss,30 it is not clear that PAR has been fully utilized to inform MS self-management research.

Work Group Planning and Recommendations

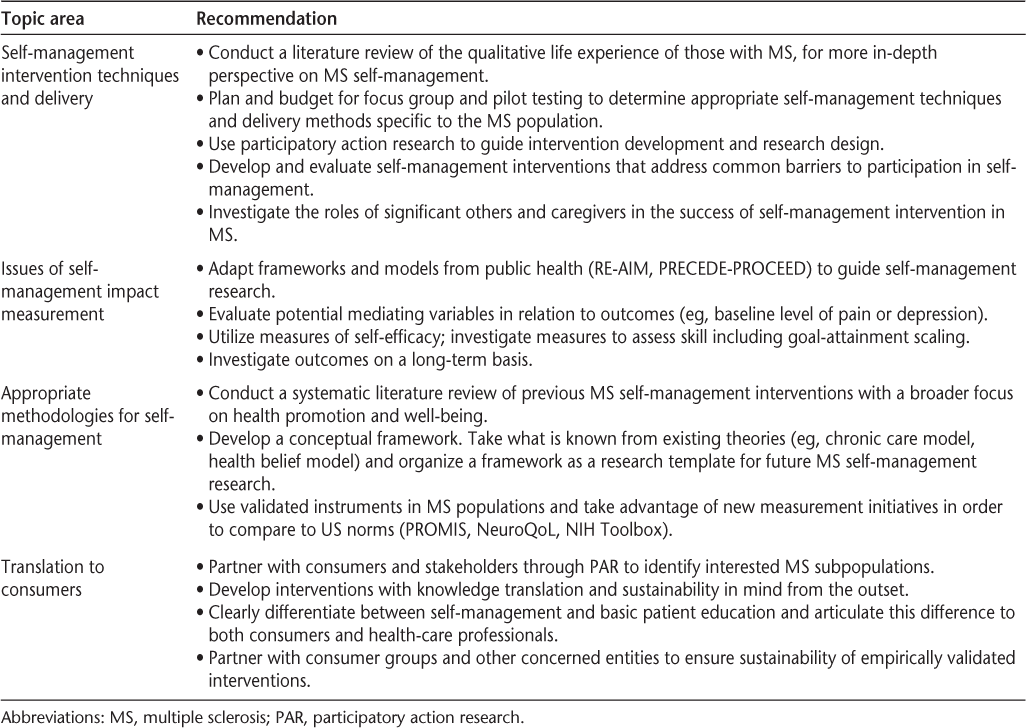

The second and third phases of the conference involved separate work group meetings, followed by a discussion of work group recommendations with all conference participants. The four work groups focused on the following topics: 1) MS self-management intervention techniques and delivery, 2) issues in self-management impact measurement, 3) appropriate methodologies for self-management, and 4) translation to consumers. A number of the work group recommendations directly addressed the self-management research deficiencies identified by the earlier presenters, including the limitations specific to the MS self-management research.

Recommendations were related to achieving more comprehensive and participant-inclusive planning in MS self-management research interventions, consideration of subgroup concerns (eg, concerns of those with more significant cognitive impairment), the adaptation of frameworks and models from public health to facilitate MS self-management research and translation, the use of more precise and validated measurement instruments relevant to MS on a longer-term basis, and translating evidence-based interventions to consumers in a sustainable manner. Specific recommendations from the work groups are presented in Table 3.

Summary of recommendations of the consensus conference by work group topic

Self-Management and Participatory Action Research

An important recommendation to come from this conference is for the use of PAR methods in designing, evaluating, disseminating, and translating self-management interventions. PAR, which is similar to the construct of community-based participatory research (CBPR) in the public health literature, and elements of this approach to research are aptly summarized in a systematic review of CBPR by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.51 This review defines CBPR as “a collaborative research approach that is designed to ensure and establish structures for participation by communities affected by the issue being studied, representatives of organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process to improve health and well-being through taking action, including social change” (p. 22). This approach involves: 1) “co-learning and reciprocal transfer of expertise” by researchers and consumers alike, 2) “shared decision making power,” and 3) “mutual ownership of the processes and products” resulting from the research collaboration (p. 3). PAR also entails “meaningful consumer involvement in all phases of the research process” and “mutual respect for the different provinces of knowledge that the team members have” (p. S3).52

PAR and CBPR combine traditional research methods with community capacity-building strategies in order to bridge the gap between knowledge produced through research and community health practice.53 54 Improved social validity, research quality, and knowledge translation have been attributed to PAR and CBPR approaches to intervention research.51 55 56 The partnership between community organizations and academic researchers in the PAR process lends itself to long-term sustainability and is an important consideration in the design of self-management programming.54 57 58 A study of a self-management intervention for people with limb loss that used a PAR approach throughout all stages of the research30 showed the effectiveness of this approach in facilitating program longevity. A model of how to implement PAR in rehabilitation intervention research can be found in Ehde et al.59

Next Steps: Summary and Recommendations

This meeting was a critical step in the promotion and formulation of the research agenda in self-management research for people with MS. Both expert presenters and work group participants underscored a number of self-management research priorities.

As self-management research funding is also of concern, interagency and nonprofit organization collaboration is likely to be an effective route of 1) promoting interdisciplinary thinking, 2) distributing funding burden in the context of a challenging economic climate, and 3) facilitating breadth and depth of dissemination activities. Partnerships involving federal agencies (such as the CDC, NIDRR, and NIH), academic centers (such as the MS RRTC), major MS treatment and research facilities (represented by MS Centers of Excellence/CMSC members), and advocacy groups such as the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and its affiliates are critical.

This first conference was an important step in advancing research on self-management in MS. A template has been established for additional work and discussion. Further dialogue needs to occur at major national meetings such as the CMSC (eg, the Psychosocial Research Committee), with adequate representation of governmental, academic, and nonprofit research organizations.

PracticePoints

People with MS must manage the day-to-day effects of the disease on their lives. Self-management interventions may be helpful in this challenge.

Although a few studies focusing on specific conditions such as fatigue have suggested that self-management interventions may be beneficial, there is a paucity of evidence supporting the use of such interventions in MS.

Participatory action research methods should be used in designing, evaluating, disseminating, and translating self-management interventions.

Partnerships involving governmental, academic, and nonprofit organizations are critical to the advancement of research on self-management in MS.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Laura Henderson for work in coordinating the consensus conference.

References

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. About MS: who gets MS? 2006. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/Who%20gets%20MS.asp. Accessed October 25, 2006.

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2002; 359: 1221–1231.

Sutliff MH. Contribution of impaired mobility to patient burden in multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010; 26: 109–119.

Jongen PJ, Ter Horst AT, Brands AM. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Minerva Med. 2012; 103: 73–96.

Costello K, Harris C. Differential diagnosis and management of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: considerations for the nurse. J Neurosci Nurs. 2003; 35: 139–148.

Romani A, Bergamaschi R, Candeloro E, Alfonsi E, Callieco R, Cosi V. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: multidimensional assessment and response to symptomatic treatment. Mult Scler. 2004; 10: 462–468.

Bethoux F. Fatigue and multiple sclerosis. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2006;49:265–271, 355–360.

O'Connor AB, Schwid SR, Herrmann DN, Markman JD, Dworkin RH. Pain associated with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and proposed classification. Pain. 2008; 137: 96–111.

Nyenhuis DL, Rao SM, Zajecka JM, Luchetta T, Bernardin L, Garron DC. Mood disturbance versus other symptoms of depression in multiple sclerosis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995; 1: 291–296.

Patten SB, Beck CA, Williams JVA, Barbui C, Metz LM. Major depression in multiple sclerosis: a population-based perspective. Neurology. 2003; 61: 1524–1527.

Goldman Consensus Group. Goldman consensus statement on depression in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 328–337.

Bamer AM, Cetin K, Johnson KL, Gibbons LE, Ehde DM. Validation study of prevalence and correlates of depressive symptomatology in multiple sclerosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008; 30: 311–317.

Bamer AM, Johnson KL, Amtmann D, Kraft GH. Prevalence of sleep problems in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008; 14: 1127–1130.

Bamer AM, Johnson KL, Amtmann DA, Kraft GH. Beyond fatigue: assessing variables associated with sleep problems and use of sleep medications in multiple sclerosis. Clin Epidemiol. 2010; 2: 99–106.

Brass SD, Duquette P, Proulx-Therrien J, Auerbach S. Sleep disorders in patients with multiple sclerosis. Sleep Med Rev. 2010; 14: 121–129.

Kaminska M, Kimoff RJ, Schwartzman K, Trojan DA. Sleep disorders and fatigue in multiple sclerosis: evidence for association and interaction. J Neurol Sci. 2011; 302: 7–13.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001; 20: 64–78.

Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998; 1: 2–4.

Ryan P, Sawin KJ. The individual and family self-management theory: background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nurs Outlook. 2009;57:217–225.e216.

Institute of Medicine, Committee on Identifying Priority Areas for Quality Improvement, Adams K, Corrigan J. Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002; 48: 177–187.

Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003; 26: 1–7.

Jordan JE, Osborne RH. Chronic disease self-management education programs: challenges ahead. Med J Aust. 2007; 186: 84–87.

Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Unending Work and Care: Managing Chronic Illness at Home. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1988.

Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004; 119: 239–243.

Heinrich E, De Vries NK, Schaper NC. Self-management interventions for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Eur Diabetes Nurs. 2010; 7: 71–76.

Jovicic A, Holroyd-Leduc JM, Straus SE. Effects of self-management intervention on health outcomes of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2006; 6:43.

Bosworth HB, Powers BJ, Oddone EZ. Patient self-management support: novel strategies in hypertension and heart disease. Cardiol Clin. 2010; 28: 655–663.

Gao WJ, Yuan CR. Self-management programme for cancer patients: a literature review. Int Nurs Rev. 2011; 58: 288–295.

Wegener ST, Mackenzie EJ, Ephraim P, Ehde D, Williams R. Self-management improves outcomes in persons with limb loss. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009; 90: 373–380.

Battersby M, Von Korff M, Schaefer J, et al. Twelve evidence-based principles for implementing self-management support in primary care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010; 36: 561–570.

Devins GM, Shnek ZM. Multiple sclerosis. In: Frank RG, Elliott TR, eds. Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000:163–184.

Rae-Grant AD, Turner AP, Sloan A, Miller D, Hunziker J, Haselkorn JK. Self-management in neurological disorders: systematic review of the literature and potential interventions in multiple sclerosis care. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011; 48: 1087–1100.

Bishop M, Frain M. Development and initial analysis of the Multiple Sclerosis Self-Management Scale. Int J MS Care. 2007; 9: 35–42.

Bishop M, Frain MP, Tschopp MK. Self-management, perceived control, and subjective quality of life in multiple sclerosis: an exploratory study. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2008; 52: 45–56.

Knaster ES, Yorkston KM, Johnson K, McMullen KA, Ehde DM. Perspectives on self-management in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2011; 13: 146–152.

Stuifbergen AK, Becker H, Blozis S, Timmerman G, Kullberg V. A randomized clinical trial of a wellness intervention for women with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003; 84: 467–476.

Bombardier CH, Cunniffe M, Wadhwani R, Gibbons LE, Blake KD, Kraft GH. The efficacy of telephone counseling for health promotion in people with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008; 89: 1849–1856.

Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, et al. Telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62: 1007–1014.

Mohr DC, Likosky W, Bertagnolli A, et al. Telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000; 68: 356–361.

Finlayson M, Preissner K, Cho C, Plow M. Randomized trial of a teleconference-delivered fatigue management program for people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011; 17: 1130–1140.

Medco. Results of Medco Health's health management program for multiple sclerosis shows positive impact on patient health. Business Wire. 2003;April 10.

Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010; 63: 1179–1194.

Perez L, Huang J, Jansky L, et al. Using focus groups to inform the Neuro-QOL measurement tool: exploring patient-centered, health-related quality of life concepts across neurological conditions. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007; 39: 342–353.

Gershon RC, Cella D, Fox NA, Havlik RJ, Hendrie HC, Wagster MV. Assessment of neurological and behavioural function: the NIH Toolbox. Lancet Neurol. 2010; 9: 138–139.

Amtmann D, Bamer A, Cook K, Askew R, Noonan V, Brockway J. UW-SES: a new self-efficacy scale for people with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012; 7:7.

Amtmann D, Bamer A, Cook K, Harniss M, Johnson K. Adapting PROMIS physical function items for users of assistive technology. Disabil Health J. 2010; 3:e9.

Wazenkewitz JL, Ehde DM. Developing a telephone-delivered self-management intervention. Int J MS Care. 2011;13(suppl 3):86–87.

Bombardier CH, Cunniffe M, Wadhwani R, Gibbons LE, Blake KD, Kraft GH. The efficacy of telephone counseling for health promotion in people with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008; 89: 1849–1856.

Newman S, Steed L, Mulligan K. Self-management interventions for chronic illness. Lancet. 2004; 364: 23–29.

R. T. I. International–University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. 2004. http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS53325.

White GW, Suchowierska M, Campbell M. Developing and systematically implementing participatory action research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4 suppl 2):S3–12.

Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008.

Cornwall A, Jewkes R. What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med. 1995; 41: 1667–1676.

Kerner J, Rimer B, Emmons K. Introduction to the Special Section on Dissemination: Dissemination research and research dissemination: how can we close the gap? Health Psychol. 2005; 24: 443–446.

Slater JS, Finnegan JR Jr, Madigan SD. Incorporation of a successful community-based mammography intervention: dissemination beyond a community trial. Health Psychol. 2005; 24: 463–469.

Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where's the practice-based evidence? Fam Pract. 2008;25(suppl 1):i20–24.

Green LW, Glasgow RE, Atkins D, Stange K. Making evidence from research more relevant, useful, and actionable in policy, program planning, and practice slips “twixt cup and lip.” Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6 suppl 1):S187–191.

Ehde DM, Wegener ST, Williams RM, et al. Developing, testing and sustaining rehabilitation interventions via participatory action research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(1 suppl):S30–42.

Consensus Conference Participants: Dagmar Amtmann, PhD; William Anthony; Christopher Bever, Jr, MD, MBA; Malachy Bishop, PhD, CRC; Charles Bombardier, PhD; Allen Bowling, MD, PhD; Teresa Brady, PhD; Ruth Brannon, MSPH, MA; Jack Burks, MD; Karon Cook, PhD; Kevin Dougherty, MA, LPC; Dawn Ehde, PhD; Marcia Finlayson, PhD, OTR/L; Fred Foley, PhD; Sue Forwell, PhD, OT, FCAOT; Robert Fraser, PhD; June Halper, APN-C, MSCN, FAAN; Allen Heinemann, PhD, ABPP (RP); Laura Henderson, BS; Lisa Iezzoni, MD, MSc; Erica Johnson, PhD, CRC; Kurt Johnson, PhD; Patricia Kennedy, RN, CNP, MSCN; Jiseon Kim, PhD; George H. Kraft, MD, MS; Nicholas LaRocca, PhD; Nancy Law, PhD; Heidi Maloni, PhD, ANP-BC; Deborah Miller, PhD; Ralph Nitkin, PhD; Kenneth Pakenham, PhD; Phil Rumrill, PhD, CRC; Alan Segaloff, CPA; Arthur Sherwood, PhD; Alexa Stuifbergen, PhD, RN, FAAN; Aaron Turner, PhD; Aimee Verrall, MPH; Jamie Wazenkewitz, MSW, MPH, LSWAIC.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Kraft is on the Axon Council for Acorda Therapeutics; National Advisory Board of the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research; Advisory Board of the Kessler Research Institute, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey; and Professional Advisory Board of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: The consensus conference was funded jointly by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR). The contents of this article were developed under a grant from the Department of Education, NIDRR grant number H133B080025. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.