Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Attributional Style and Depression in Multiple Sclerosis

Several etiologic theories have been proposed to explain depression in the general population. Studying these models and modifying them for use in the multiple sclerosis (MS) population may allow us to better understand depression in MS. According to the reformulated learned helplessness (LH) theory, individuals who attribute negative events to internal, stable, and global causes are more vulnerable to depression. This study differentiated attributional style that was or was not related to MS in 52 patients with MS to test the LH theory in this population and to determine possible differences between illness-related and non-illness-related attributions. Patients were administered measures of attributional style, daily stressors, disability, and depressive symptoms. Participants were more likely to list non-MS-related than MS-related causes of negative events on the Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ), and more-disabled participants listed significantly more MS-related causes than did less-disabled individuals. Non-MS-related attributional style correlated with stress and depressive symptoms, but MS-related attributional style did not correlate with disability or depressive symptoms. Stress mediated the effect of non-MS-related attributional style on depressive symptoms. These results suggest that, although attributional style appears to be an important construct in MS, it does not seem to be related directly to depressive symptoms; rather, it is related to more perceived stress, which in turn is related to increased depressive symptoms.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, unpredictable, and degenerative disease that causes a variety of symptoms affecting patients' quality of life. The disease course is highly variable, its outcome is hard to predict, and there is no known cure. Depression is extremely common in MS, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of up to 50%.1 This prevalence rate is higher than that found in the general population and in people with most other chronic diseases.2 3 However, the etiology of depression in people with MS remains unclear.

Although biological, psychological, and social factors are thought to be involved in depression in MS, individually they show weak or inconsistent relationships. For instance, although some studies show that a combination of the most robust neuropathology measures explains 43% of the variance in depression in MS,4 other studies have not found strong relationships between neuropathology and depression. Furthermore, MS symptoms such as physical disability, pain, and cognitive dysfunction also demonstrate inconsistent or weak relationships with depression.5 Therefore, interaction among biological, psychological, and social factors seems most likely to predict depressive symptoms in these patients. However, the most conducive combination of factors and the nature of the possible interactions are still unknown. Adapting models of depression used in the general population to MS may improve our understanding of these complex interactions.

The Learned Helplessness Theory of Depression

One popular model of depression used in the general population is the learned helplessness (LH) theory. Given the pervasive, unpredictable, and uncontrollable nature of MS and the lack of a known cure, it is understandable that patients might feel helpless in the face of their disease, and this has been found previously.6 However, few studies have examined attributional style in MS or attempted to apply the LH theory to a population with MS.

According to the reformulated version of the LH theory, an individual who experiences uncontrollable negative events may subsequently develop a negative attributional style, whereby the person is more likely to expect future negative events to occur and to become depressed if and when they occur.7 The attributions that lead to such a cognitive vulnerability are described as depressogenic and are thought to be internal, stable, and global. Thus, a person with a depressogenic attributional style perceives the causes of negative events as arising from personal factors (internal), as persisting for a long period of time (stable), and as being present in all situations (global).

A depressogenic attributional style represents a cognitive vulnerability to depression and must be present along with negative events to produce depression. Therefore, there are two processes involved—the initial formation of the depressogenic attributional style and the subsequent triggering of depression by negative events once the vulnerability is in place. The current study focused on the former process; however, because of the multiple roles of stressors in the LH model, an alternative hypothesis for the current study identifies stressors as a mediator instead of attributional style.

The few investigations to date that have examined aspects of the LH model in MS have found support for it. Patients were found to have more stable attributions for negative events than controls,8 and depression was found to be correlated with global and stable attributions for negative events.9 Additionally, in the latter study, general and MS-related stress interacted with attributional style to predict depressive symptoms cross-sectionally.

The Learned Helplessness Model in an MS Population

Although the LH model does seem relevant in MS, the concepts involved may apply differently in MS patients. For instance, such patients may have very different cognitive styles relating to their disease than to other aspects of their lives. Also, it is not clear to what degree MS patients attribute negative events to their MS. Furthermore, it is difficult to predict whether internal, stable, and global attributions about MS and its symptoms would be depressogenic, since MS and its symptoms are related to personal factors, are present in many areas, and will be present for a long period of time. To our knowledge, no reported studies have separated MS-related and non-MS-related attributional style, although there is a theoretical basis for this separation.

According to the specific vulnerability theory, depressive reactions to stressors in a given content domain are best predicted by attributional styles for that particular domain.10 To date, only the affiliative and achievement domains have been examined,11 and this distinction has not been studied in MS. It is possible that attitudes related to one's MS may have different effects from those unrelated to illness and interact differentially with MS-related versus non-MS-related negative events. For example, MS patients may be more likely to become depressed if they have ongoing negative experiences related to their MS symptoms and develop a depressogenic attributional style toward their MS than if they develop a depressogenic attributional style about another area of their life. Besides the specific vulnerability theory, another variation of the LH model is the exclusion of internal attributions. Some researchers have proposed that internal attributions alone are not always maladaptive (eg, attributing failing a test to a lack of effort, which leads to increased studying).10 Similarly, internal attributions about disease-related events may not necessarily be maladaptive for MS patients (eg, attributing not getting enough work done to one's fatigue). Given this proposed alteration of the LH model and the possible differences in MS attributions, in the current study attributional style was analyzed with and without the internal dimension.

Study Aims

Because the current study was cross-sectional, with a correlational method, we were not able to test causal models. For each proposed mediational model, correlational analyses were conducted first to determine whether the relationships in the pathway were significant. If so, the mediation model was tested.

The aims of the study were as follows:

1) To determine the nature of MS patients' attributions, the frequency of MS-related attributions, and any differences between attributions in the affiliative and achievement domains; and to examine whether MS-related and non-MS-related attributional styles relate differently to depression, demographic, and disease-related variables.

2) To test whether depressogenic attributional style mediates the relationship between overall stressors (MS-related and not) and depressive symptoms.

3) To determine whether depressogenic attributional style regarding non-MS-related causes of events mediates the relationship between daily stressors and depressive symptoms.

4) To examine whether a depressogenic attributional style regarding MS-related causes of events mediates the relationship between disability and depressive symptoms.

5) To determine whether attributional style serves as a mediator without the internal dimension (ie, only the stable and global dimensions). These analyses would be the same as for aims 2 and 3 above but without the internal dimension of the Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Fifty-nine individuals with MS were tested as part of a larger longitudinal study. Participants with MS were recruited through advertising in a newsletter distributed in western Pennsylvania, MS support groups in the central Pennsylvania area, and flyers distributed in the State College (PA) community. All individuals were confirmed to have definite MS by their treating neurologist, who returned a mailed form that indicated a diagnosis rating and course type rating based on accepted criteria.12 Participants were given $100 as compensation for testing. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the Behavioral Committee of the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board.

Participants were excluded if they had any of the following: a) history of neurologic disease other than MS, b) history of drug or alcohol abuse, c) history of developmental learning disability, d) visual or motor disturbances that would prohibit testing without significant alteration of testing procedures, or e) a clinical exacerbation less than 4 weeks before the study. Six of the 59 participants enrolled in the study were excluded from analyses because they were missing half or more of the items on the ASQ. Additionally, one participant was a univariate outlier on the Chicago Multiscale Depression Inventory (CMDI), one of the measures used in the study, and so was excluded. After these exclusions, there were 52 participants left in the study.

Measures

The ASQ used in this study is a self-report measure that asks participants to imagine six hypothetical negative events.13 For each event, the participant is instructed to write down one possible cause of the event and then to rate from 1 to 7 how internal, stable, and global that cause is (with descriptions of these dimensions provided). The events in the questionnaire were “not being able to find a job,” “not helping a friend that comes to you for help,” “giving a talk that the audience reacts negatively to,” “having a friend act hostilely towards you,” “not being able to get all your work done,” and “going on a date that goes badly.”

For each participant, average scores were calculated for each individual dimension (internal, stable, and global), as well as for the overall ASQ (an average of all three dimensions). Separate averages were then created for MS-related and non-MS-related causes. A clinical neuropsychologist and researcher specializing in MS (P.A.) coded the causes listed by participants on the ASQ as MS-related or non-MS-related. He was given detailed coding instructions and instructed to code the cause as MS-related only if it was clearly related to MS or a common MS symptom.

The CMDI is a self-report measure that was designed specifically to measure depressive symptoms in chronically ill populations.14 The measure consists of mood, evaluative, and vegetative scales. To eliminate confounding between MS symptoms and vegetative depressive symptoms, and in order to follow the recommendation of Nyenhuis et al.15 and the precedent of earlier work,16 only the mood and evaluative subscales were included in the analyses. In order to more thoroughly measure depression, the Beck Depression Inventory–Fast Screen (BDI-FS) was also used.17 This measure consists of seven items from the BDI-II and has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of depression in the MS population.18

The Hassles and Uplifts Scale (HUS) is a measure of everyday stressors and positive experiences designed for a middle-aged population.19 The measure was designed to capture daily stressors as well as more momentous negative life events. Participants rate 53 items on a 4-point scale based on how much of a hassle or an uplift the referent in the item has been over the past month. Items are words or phrases that address various life domains such as work, family, and finances. In order to best fit the LH model and to mirror the disability measure, only the summed hassles score was used.

The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) is a performance-based measure of disability that includes upper- and lower-extremity motor functioning (a Timed 25-Foot Walk and the Nine-Hole Peg Test) as well as a measure of cognitive functioning (the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test [PASAT]).20 The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) is a commonly used disability measure based on ambulation and neurologic symptoms.21 In this study, participants rated themselves from 0 to 10, with higher ratings indicating greater disability. A rating of 0 corresponds to no physical disability or disturbance in functional systems, 9.5 corresponds with extreme functional system disturbance (inability to communicate or eat), and 10 corresponds with death due to MS. Self-reported EDSS ratings have been shown to be highly correlated with neurologist ratings,22 and using self-reported disability measures is a well-established and validated method in MS research.23 The overall stressors score (for study aim 2) was calculated by converting the Hassles, EDSS, and MSFC scores to z scores and averaging them.

Data Pre-processing

The mood and evaluative scores on the CMDI were converted to t scores and averaged using the healthy controls of Nyenhuis and colleagues15 as the reference point. These t scores were found to be positively skewed even after excluding the univariate outlier, so a negative inverse transformation was used. All scores were converted to z scores for regression analyses so that all variables were on the same scale and beta weights could be interpreted. For the MSFC, z scores were created for each task relative to published norms24 and averaged to create a composite z score. For the Timed 25-Foot Walk, three participants were in wheelchairs and unable to complete the test, so they were given a score of 1 second longer than the longest time recorded (20 seconds). Because of experimenter error, two participants who used a cane were not tested, but in order to retain these subjects in the study and include a broad range of disability levels, they were given the average score of the four participants who were tested and used canes (10.57 seconds). The MSFC z scores were inverted so that higher scores on this and all other variables indicated more pathology.

Results

Demographics and Disease-Related Variables

All 52 participants were white, and 45 (87%) were female. Participants had an average of 15 (SD = 2) years of education and an average age of 52 (SD = 9.5) years. Thirty-two (62%) had a relapsing-remitting course, 13 (25%) had a secondary progressive course, 4 (8%) had a primary progressive course, and 3 (6%) had a progressive relapsing course. Twenty-seven participants (52%) were currently working. The group's average EDSS score was 4.0, which indicates a limitation in walking ability with no need for walking assistance. Participants had been diagnosed with MS for an average of 15 years. Finally, participants' average mood and evaluative t score on the CMDI was 49 and their average total BDI-FS score was 4.5.

Correlations between depressive symptoms and demographic and disease-related variables were examined to determine whether any covariates were needed for the mediational analyses. As course type is a categorical variable, a t test was conducted to compare depressive symptoms between patients with relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive courses (the two most prevalent course types). These groups did not differ (t 43 = −0.22, mean difference = 0.00). Duration since diagnosis was the only demographic or disease-related variable that significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.31, P < .05); thus, it was used as a covariate in all non-illness-related mediational models. This was not controlled for in illness-related regressions because disability is a variable of interest in these regressions, and thus controlling for duration since diagnosis would likely remove meaningful variance.

Descriptive Analysis of the ASQ: Aim 1

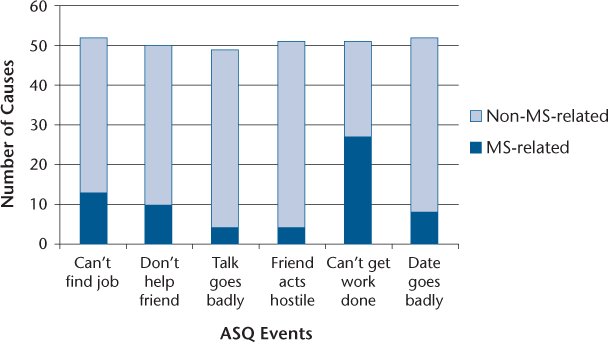

Twenty-five participants with MS did not list any MS-related causes on the ASQ. One participant listed only MS-related causes. Therefore, subsequent MS-related analyses included 27 participants and non-MS analyses included 51 participants. For the six negative events in the ASQ, an average of 22% of causes listed for each event were coded as MS-related (range, 8–53%). The events most likely to be attributed to an MS-related cause were not being able to get the work done that is expected of them, and not being able to find a job (53% and 25%, respectively; Figure 1). Overall, MS-related causes were rated as being significantly more internal, stable, and global than non-MS-related causes (t 76 = 8.37, P < .0001; mean difference = 1.69). Participants made significantly more MS-related attributions for work-related events than for relationship-related events (χ1 2 = 8.70, P < .01). Participants also rated significantly more causes as MS-related for one specific event—not being able to get the work done that is expected of them—than for all of the other events (χ1 2 = 33.20, P < .0001).

Types of causes listed by patients on the Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ)

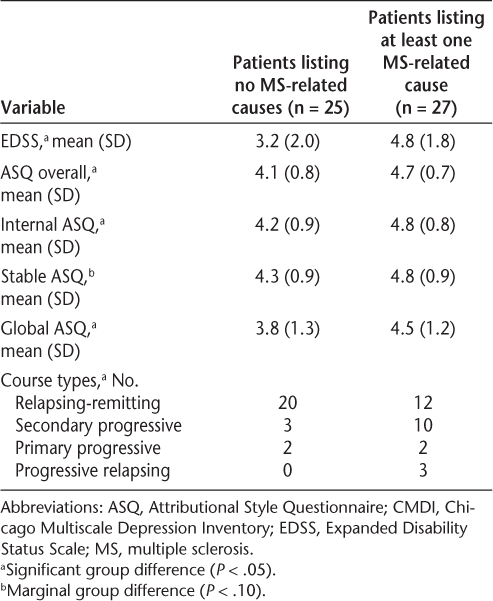

When participants who listed no MS-related causes were compared with those reporting at least one MS-related cause, the group who listed MS-related causes had significantly greater disability, a more depressogenic attributional style overall, more internal and global attributions, and marginally more stable attributions (Table 1). Also, the group listing MS-related causes had significantly more participants with secondary progressive and progressive relapsing courses (χ3 2 = 8.71, P < .05). The group differences in overall, internal, and global attributional style remained significant after controlling for disability and course type (P < .01), and the difference in global attributional style became marginal (P < .10).

Differences between patients listing MS-related causes and patients not listing any MS-related causes

Mediation Analyses: Aims 2 to 5

Mediation models were tested when correlations for proposed pathways were significant. Duration since diagnosis was used as a covariate in all non-illness-related mediation models. Mediation models were tested using an SPSS macro published by Preacher and Hayes (2008) that estimates path coefficients and generates bootstrap confidence intervals.25 When correlations were examined for study aim 2, it was found that overall attributional style was correlated with overall stressors but not with depressive symptoms (Table 2), and so a mediational model was not tested for this pathway.

Correlations between relevant variables in MS patients

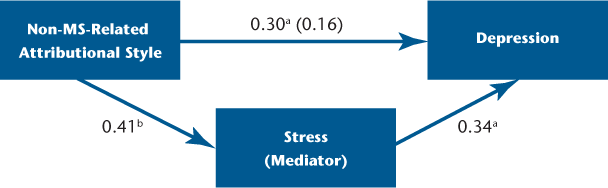

When study aim 3 was tested, non-MS-related attributional style correlated significantly with stress and depressive symptoms (Table 2). Given these significant correlations, the mediation model was examined but found to be not significant; specifically, there was no significant effect of the mediator (non-MS-related attributional style) on depressive symptoms. Conversely, we found that stress mediated the effect of non-MS-related attributional style on depressive symptoms (R 2 = 0.26, F 3,47 = 5.6, P < .01) (Figure 2). A bootstrapping method with 5000 resamplings was used to generate confidence intervals for the indirect effects in this pathway. The indirect effect of non-MS-related attributional style on depressive symptoms through stressors (hassles) was different from zero with 95% confidence (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.01–0.34; bias corrected and accelerated), thus supporting the mediation effect. This represented complete mediation, as the direct effect of non-MS-related attributions on depressive symptoms was not significant after controlling for the effect of the mediator, stressors (hassles). This suggests that the relationship between non-MS-related attributional style and depressive symptoms is completely explained by its relationship with stressors (hassles). According to regression analyses, 51% of the variance in depressive symptoms was explained by this model.

Significant mediation model

For study aim 4, MS-related attributional style did not correlate with either disability or depressive symptoms (Table 2). Therefore, a mediational model was not tested for this aim. With regard to aim 5, when the internal dimension was removed, non-MS-related stable and global attributional style correlated with hassles and depressive symptoms. However, when the mediation model was tested, it was not significant. MS-related stable and global attributional style did not correlate with disability or depressive symptoms. Therefore, this mediational model was not tested.

Discussion

This study found that attributional style did not mediate the effect of stressors on depressive symptoms. This was true regardless of whether it was the MS or non-MS domain or whether the internal dimension was included. Instead, it was found that daily stressors mediated the effect of non-MS-related attributional style on depressive symptoms. Additionally, descriptive analysis of the ASQ revealed that work-related events were most likely to be attributed to MS, but that, overall, patients listed mostly non-MS-related causes.

Interpretation of Results

Descriptive Analyses of the ASQ

To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe in detail the types of causes MS patients generate for negative events on the ASQ and to analyze attributional style for MS-related and non-MS-related causes separately. We found that the majority of causes listed by patients were non-MS-related, suggesting that individuals with MS do not necessarily see their MS as affecting most areas of their life. This suggests that patients can maintain several different self-aspects or identities, which has been shown to be adaptive in healthy populations.26 Additionally, more-disabled patients attributed more negative events to their MS. This suggests that more-disabled patients may, quite realistically, see their MS as affecting more areas of their life (such as work and relationships) while less-disabled patients may be able to keep their MS relatively separate from other areas of their life.

Additionally, MS-related causes were rated more depressogenically by all participants, indicating that MS and its symptoms may realistically be seen by patients as fairly internal, stable, and global. The lack of correlation between disability and overall or MS-related attributional style was surprising and may be due to the low power for MS-related attributions, the relatively mild disability level in this sample, and the fact that most ratings overall were non-MS-related. This descriptive analysis also revealed that patients were more likely to attribute work-related events than interpersonal events to MS-related causes (such as not getting their work done and not finding a job). MS detrimentally affects many patients' ability to work,27 so it is possible that work is more directly affected by participants' MS symptoms such as cognitive deficits, fatigue, and physical limitations. In fact, one study on degree of illness intrusiveness indicated that MS patients felt their MS interfered more with their work than with their relationships.28 Previous studies have examined attributional style separately in the affiliative and achievement domains in healthy populations, and our results suggest that this division may also be helpful in the MS population.

Correlational and Mediational Analyses

Based on the reformulated LH theory, it was predicted that attributional style (in the MS or non-MS domain) would act as a mediator between stressors (disability or daily hassles) and depressive symptoms. This hypothesis was not supported in any models analyzed. Instead, we found that the relationship between attributional style in the non-MS domain and depressive symptoms was explained by the mediator effect of stressors (hassles).

Although this was not the predicted mediation, there are many possible reasons for this model's significance. First, there is a large body of research supporting the stress generation effect, which refers to the finding that individuals vulnerable to depression (those with current depression or with a recent remission of depression) often experience more negative events, usually interpersonal in nature, that are dependent on their behavior.29 Individuals with negative cognitive styles have also been shown to experience and report more of this type of stress.29 Additionally, depressed individuals are known to have negative memory biases,30 a finding that has been replicated in MS studies.31 Therefore, it is possible that the hassles score in our study reflected patients' perceptions and memories of their daily stressors and not their objective amount of stressors. In other words, individuals with a depressogenic attributional style may be more likely to both objectively experience and also remember their daily lives as more stressful than those with a healthier attributional style, and these experiences and memories may be associated with increased risk for depressive symptoms.

The lack of significant correlations in the MS-related pathway (ie, between disability, MS-related attributional style, and depressive symptoms) was surprising. The lack of correlations in the MS domain may indicate that MS-related attributions act differently than non-MS-related attributions in this population; alternatively, it may be due to the limited range of disability and depressive symptoms in this sample. Regardless, it is not clear whether or how disability or MS-related attributional style fits into the LH model for individuals with MS.

Finally, with regard to the internal dimension, we found that for the non-MS domain, attributional style with and without the internal dimension correlated with depressive symptoms (and hassles). However, the significant mediational model (with hassles as the mediator) was significant only with the internal dimension included. For the MS domain, attributional style did not correlate with depressive symptoms with or without the internal dimension. At the least, the current findings do not reject the utility of the internal dimension in the LH model in this population.

Clinical Implications

Because attributional style is part of one pathway to depressive symptoms in individuals with MS, it may represent a malleable target for cognitive therapy. Previous research has shown that attributional style can be changed through psychotherapy.32 33 Therefore, if attributional style can successfully be changed, patients with MS might experience fewer objective stressors and perceive their daily life as less stressful, and thus perhaps be less likely to experience depressive symptoms. Treatment studies could be conducted that are focused on modifying attributional style and perceptions of stress. Our study also suggests that clinicians working with individuals with MS (especially less-disabled patients) should remember that patients will not necessarily attribute all negative events to their MS. Lastly, our study suggests that counseling specifically focused on employment issues may be especially helpful for individuals with MS. Although clinicians cannot directly change the day-to-day stress in MS patients' lives or their biological risk factors for depression, through attention to patients' attributional style they may be able to alter patients' perceptions and experiences of stress and thereby decrease the likelihood of depressive symptoms.

Limitations

Although this study used a novel method for analyzing illness-related and non-illness-related attributional style, it had a few limitations. The attributional style measure used in the study was not meant to address MS-related and non-MS-related causes specifically. Hence, our measure was divided post hoc, which required an outside rater to categorize participants' responses, resulting in decreased power, especially for MS-related attributions. In fact, sometimes patients' ASQ scores were based on very few ratings—and almost half of participants had no MS-related ASQ scores at all. Therefore, the lack of findings in the MS domain may have been mainly a function of low power. However, this post hoc method allowed us to measure MS-related attributions instead of attributions made for MS-related events, as well as evaluate what types of attributions patients would provide for events not specifically related to their MS.

Additionally, because many symptoms of MS are also symptoms of depression, the MS-related causes could also have been depression-related. And because of the subjectivity of the stress measure used, it is impossible to determine whether depressogenic attributional style was associated with more perceived stress or more objective amounts of daily stress in these participants' lives. It is therefore unclear whether the same results would have been found with a more objective measure of stress or negative events.

Furthermore, the current study examined self-reported depressive symptoms in a community-based MS sample, meaning that most participants did not have a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Thus, the current results may not apply to more severe depression. Relatedly, when we confined depression symptoms to only mood and evaluative symptoms, our MS group was comparable to healthy controls in terms of their self-reported depression. Lastly, because this study was cross-sectional, there is a limit to our interpretation of the mediation results. Prospective studies are needed to more validly test these mediation models.

Conclusion

The LH theory and attributional style are important constructs to consider when examining depressive symptoms in individuals with MS. Additionally, attributions seem to have different effects when they are illness-related versus non-illness-related. However, our results suggest that non-MS-related attributional style is related to more perceived stress, which in turn is associated with increased depressive symptoms. Future studies should use longitudinal designs, more-specialized illness-related and non-illness-related attributional style measures, and interview-based measures of stress and negative life events along with self-report.

PracticePoints

Attributional style seems to be part of one path-way to depressive symptoms in MS; therefore, it may be a malleable target for cognitive therapy in MS patients. In addition, addressing patients' attributional style may lead to decreased perceptions of everyday stress.

MS patients tend to view their work as being more affected by their MS than their interpersonal functioning. Thus, counseling focused on employment issues may be especially helpful for employed patients.

In general, MS patients seem to attribute most negative events to factors other than their MS.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many neurologists in the Pennsylvania region who contributed their time to verifying MS diagnoses and ratings for the MS participants in the project. We would also like to thank the MS participants for taking part in this study. We offer special thanks to Amanda Rabinowitz, Fiona Barwick, Dede Ukueberuwa, Karen Gasper, and Frank Hillary for their help with various aspects of the project. These data, in part, were presented at the 30th annual meeting of the National Academy of Neuropsychology in October 2010 in Vancouver, British Columbia, and at the 39th annual meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society in February 2011 in Boston, Massachusetts. This project was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Science degree at The Pennsylvania State University granted to Ms. Vargas.

References

Patten SB, Metz LM, Reimer MA. Biopsychosocial correlates of lifetime major depression in a multiple sclerosis population. Mult Scler. 2000; 6: 115–120.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. The Lancet. 2007; 370: 851–858.

Feinstein A, O'Connor P, Akbar N, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging abnormalities in depressed multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2010; 16: 189–196.

Arnett PA, Barwick FH, Beeney JE. Depression in multiple sclerosis: review and theoretical proposal. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008; 14: 691–724.

Shnek ZM, Foley FW, LaRocca NG, et al. Psychological predictors of depression in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Rehabil. 1995; 9: 15–23.

Abramson LY, Seligman MEP, Teasdale J. Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation. J Abnorm Psychol. 1978; 87: 49–74.

Johnson SK, Lange G, Tiersky L, et al. Health-related personality variables in chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis. J Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2001; 8: 41–52.

Kneebone II, Dunmore E. Attributional style and symptoms of depression in persons with multiple sclerosis. Int J Behav Med. 2004; 11: 110–115.

Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: a theory based sub-type of depression. Psychol Rev. 1989; 96: 358–372.

Abela JRZ, Seligman MEP. The hopelessness theory of depression: a test of the diathesis-stress component in the interpersonal and achievement domains. Cognit Ther Res. 2000; 24: 361–378.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011; 69: 292–302.

Peterson C, Semmel A, von Baeyer C, et al. The attributional style questionnaire. Cognit Ther Res. 1982; 6: 287–299.

Nyenhuis DL, Luchetta T, Yamamoto C, et al. The development, standardization, and initial validation of the Chicago Multiscale Depression Inventory. J Pers Assess. 1998; 70: 386–401.

Nyenhuis DL, Rao SM, Zajecka J, et al. Mood disturbance versus other symptoms of depression in multiple sclerosis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995; 1: 291–296.

Vargas GA, Arnett PA. Positive everyday experiences interact with social support to predict depression in multiple sclerosis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010; 16: 1039–1046.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-Fast Screen for Medical Patients Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2000.

Benedict RH, Fishman I, McClellan MM, et al. Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 393–396.

Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer C, et al. Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. J Behav Med. 1981; 4: 1–39.

Fischer JS, Rudick RA, Cutter GA, et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC): an integrated approach to MS clinical outcome assessment. Mult Scler. 1999; 3: 244–250.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983; 33: 1444–1452.

Solari A, Amato MP, Bergamaschi R, et al. Accuracy of self-assessment of the minimal record of disability in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1993; 87: 43–46.

Goodin DS. A questionnaire to assess neurological impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 1998; 4: 444–451.

Fischer JS, Jak AJ, Kniker JE, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC): Administration and Scoring Manual. New York, NY: National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2001.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008; 40: 879–891.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Multiple identities within a single self. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, eds. Handbook of Self and Identity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012:225–256.

Smith MM, Arnett PA. Factors related to employment status change in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 602–609.

Devins GM, Edworthy SM, Seland TP, et al. Differences in illness intrusiveness across rheumatoid arthritis, end-stage renal disease, and multiple sclerosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993; 181: 377–381.

Liu RT, Alloy LB. Stress generation in depression: a systematic review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future study. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010; 30: 582–593.

Gilboa E, Gotlib IH. Cognitive biases and affect persistence in previously dysphoric and never-dysphoric individuals. Cognit Psychol Depression. 1997; 5: 517–538.

Bruce JM, Arnett PA. MS patients with depressive symptoms exhibit affective memory biases when verbal encoding strategies are suppressed. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005; 11: 514–521.

Seligman ME, Castellon C, Cacciola J, et al. Explanatory style change during cognitive therapy for unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988; 97: 13–18.

Proudfoot JG, Corr PJ, Guest DE, et al. Cognitive-behavioural training to change attributional style improves employee well-being, job satisfaction, productivity, and turnover. Pers Indiv Differences. 2009; 46: 147–153.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This investigation was supported (in part) by a grant to Dr. Arnett from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (PP0978).