Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Relevance and Impact of Social Support on Quality of Life for Persons With Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Social support is crucial for persons with multiple sclerosis (MS). We sought to analyze differences in perceived social support in persons with MS vs controls; to study associations between perceived social support, clinical measures, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) variables in persons with MS; and to establish a predictive value of perceived social support for HRQOL.

METHODS

We studied 151 persons with MS (mean ± SD: age, 42.01 ± 9.97 years; educational level, 14.05 ± 3.26 years) and 89 controls (mean ± SD: age, 41.46 ± 12.25 years; educational level, 14.60 ± 2.44 years) using the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS), Expanded Disability Status Scale, Fatigue Severity Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, and Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (MusiQoL) questionnaire. Parametric and nonparametric statistical methods were used accordingly; P < .05.

RESULTS

Persons with MS exhibited lower scores on the MOS-SSS's overall support index (t 238 = −1.98, P = .04) and on each functional subscale (t 238 = −2.56 to −2.19, P < .05). No significant differences were found on the social support structural component (P > .05). Significant associations were observed between social support and depression and fatigue (r = −0.20 to −0.29, P < .05) and with MusiQoL dimensions (r = −0.18 to 0.48, P < .05). Multiple regression analysis showed all 4 tested models contributed to HRQOL-explained variance (41%–47%). The emotional/informational support model explained the most HRQOL variability (47%).

CONCLUSIONS

Persons with MS perceived reduced social support, presenting lower functional scores than controls. Perceived social support proved to be a predictor of HRQOL. These findings should be considered during therapeutic treatment.

Social support is a multidimensional concept referring to the emotional and financial resources provided to an individual by their environment.1 Social support plays a crucial role in individual health by facilitating adaptive behaviors when faced with stressful situations.2 Among the numerous proposed models of social support, structural and functional approaches are the most frequently used. The structural perspective addresses the size, density, and characteristics of the members that make up an individual’s social network, and the functional approach focuses on the effects of social interaction on the individual.3 4 Authors describe different types of functional support; the types most referenced in the literature are emotional support (eg, feeling loved and cared for), instrumental support (eg, financial support, access to food and clothing), and informational support (eg, receiving advice to solve problems).3,5,6

The direct and positive effects of social support on physical and mental health in patients with chronic illnesses have been thoroughly studied; social support acts as a buffer, protecting individuals against the negative effects of disease-related stressful events.7 8 Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurologic disease that generates a plethora of physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms9 that impact many components of a patient’s quality of life.10–12 Social support plays a pivotal role in a patient’s ability to cope with the disease and counteract the effects of social isolation.13 Previous MS research reports positive effects of social support on symptoms such as anxiety and depression,14 as well as improved health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in persons with MS who experience greater social support.15 16 A recent study observed that persons with MS with lower social support exhibited increased suicidal thoughts, highlighting social support’s mediating role on suicidal ideation.17 Perceived social support was also identified as a predictor of physical disability in this population.16 Persons with MS with greater social support report reduced fatigue symptoms.18 Studies focusing on the structural social support network components reported a link between support provided by significant others (eg, coworkers, health providers, other persons with MS) and physical health, whereas social support provided by family members and friends was mostly associated with mental health.19

Social support is usually assessed through self-perception questionnaires.20 In recent years, MS research has shifted toward a more patient-centered approach, which is why patient-reported outcome measures have been gaining similar if not more relevance than other clinical or neuroimaging outcomes.21 In addition to measuring outcomes, patient-reported outcome measures are designed to identify a patient’s perceptions, helping physicians understand the patient’s experience outside the clinical setting.22

Despite the growing clinical interest in the perceived social support of persons with MS, there are few publications on its relationship to MS characteristics and its effect on HRQOL. Given the availability of local data on this subject, the objectives of the present study were to analyze differences in perceived social support in persons with MS vs controls; to study associations among perceived social support, clinical measures, and HRQOL in persons with MS; and to establish a predictive value of perceived social support for HRQOL.

METHODS

Participants

A total of 151 persons with MS were recruited from 2 MS clinics in Buenos Aires, Argentina, through incidental nonprobabilistic sampling. All patients attending a neurology consultation that met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. The control group consisted of 89 sex-, age-, and education-matched volunteers with no MS diagnosis. All participants provided their written informed consent for the study as approved by the institutional ethics committees of Ramos Mejia Hospital and Buenos Aires University.

Inclusion criteria for persons with MS were a clinically defined MS diagnosis23 and age 18 to 60 years at the time of recruitment. Exclusion criteria for this group were a current or previous neurologic disorder other than MS, a history of psychotic disorder, a history of alcohol and/or substance dependence, current substance abuse, a history of relapse or corticosteroid administration in the 4 weeks preceding the study, and the presence of significant cognitive impairment (z score < −2 on the 3 subtests of the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS,24 as defined by Alonso et al25). Inclusion criteria for the control group were absence of clinical or neurologic disorders that could impact cognitive performance, no history of alcohol or substance dependence, no current substance abuse, and a Mini-Mental State Examination26 score less than 27.

Measurement Instruments

The Argentine adaptation of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS)27 by Rodriguez Espíndola and Enrique6 was implemented to assess perceived social support. The MOS-SSS is a brief, multidimensional survey that explores the structural components (eg, social network size) and functional dimensions of social support. It is composed of 20 items ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) on a Likert scale. The first item asks about social network size (ie, number of friends and family members the patient can rely on); the remaining items explore 3 social support dimensions: emotional/informational support (ie, information the patient can use to anticipate and face problems, such as suggestions and advice), affective support (ie, true expressions of affection, love, or empathy), and instrumental support (ie, access to material resources such as financial assistance, food, and clothing).6 A higher score on the MOS-SSS represents greater perceived social support. Questionnaire structure is illustrated in FIGURE S1, available online at IJMSC.org.

The Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (MusiQoL) questionnaire was used to assess HRQOL.28 The MusiQoL is a multidimensional self-report scale composed of 31 items targeting 9 HRQOL dimensions: activities of daily living; psychological well-being; symptoms; friendships; family relationships; sentimental and sexual life; and coping, rejection, and satisfaction with health care. In addition to the dimension scores, MusiQoL offers a global index score. All items follow a 6-point Likert structure ranging from 1 (never/not at all) to 5 (always/very much) and 6 (not applicable). Higher scores indicate higher HRQOL.

Depression symptoms were screened using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)29 locally adapted by Brenlla and Rodriguez.30 The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report questionnaire with a 4-point Likert scale that targets patients’ feelings and perceptions in the previous 2 weeks. A higher score indicates greater depressive symptoms.

Fatigue symptoms were quantified by the Argentine version of the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS),31 a self-report scale composed of 9 items, each presenting possible answers of increasing intensity on a 1- to 7-point Likert scale. A patient’s answers are to reflect how they felt during the previous 2 weeks, with a higher score indicating greater fatigue symptoms.

Global disability was assessed using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS),32 the most widely used disability scale in MS. The EDSS is based on measures of impairment on 8 functional systems: visual, sensory, pyramidal, cerebellar, brainstem, bowel and bladder, cerebral, and other. Scoring consists of 20 “half-points” that produce a total score that ranges from 0 to 10 points.

The Mini-Mental State Examination26 was administered only to the control group to screen for dementia and to verify a minimal level of instructional understanding. This 30-point screening technique consists of a series of tests to assess global cognitive performance: spatial and time orientation, memory (registration and delayed recall), attention, language (oral and written comprehension and expression), praxis, and visuospatial skills.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (IBM Corp). Descriptive analyses were performed for all included variables.

Differences in sex, age, level of education, and level of social support between persons with MS and controls were calculated using χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. T tests or Mann-Whitney U tests were used for continuous variables. Bivariate correlations between social support and clinico-demographic variables and between social support and HRQOL measures were investigated for the persons with MS.

Finally, multiple linear regression analyses were performed using the MusiQoL global index scores as the dependent variables. Independent variables were clinical scores (EDSS, FSS, BDI-II) and all MOS-SSS social support scores (global index score, emotional/informational support score, affectionate support score, and instrumental support score). The analyses were used to constitute 4 different predictive models of HRQOL. A P value was set at .05 for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

The persons with MS group was 65.6% women with a mean ± SD age of 42.01 ± 9.97 years and educational level of 14.05 ± 3.26 years. The control group was 70.8% women with a mean ± SD age of 41.46 ± 12.25 and educational level of 14.60 ± 2.44 years. Sex analysis showed no significant differences between groups on age and educational level (sex: χ2 = 0.69, P = .40; age: t 238 = 0.36, P = .71; educational level: z = −1.90, P = .15) (TABLE S1).

The persons with MS group was 88% relapsing-remitting MS (n = 133), 7% primary progressive MS (n = 11), and 4% secondary progressive MS (n = 7). The mean ± SD EDSS score was 2.88 ± 2.10, and there was a mean ± SD illness duration of 12.46 ± 10.07 years. Mean ± SD depression score on the BDI-II was 13.61 ± 9.83 and perceived fatigue score on the FSS was 4.15 ± 2.27.

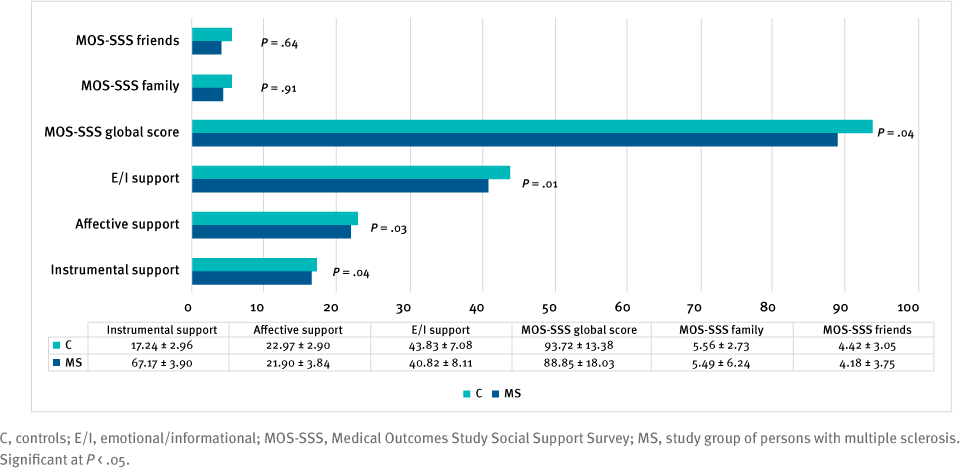

There were significant differences in perceived social support between persons with MS and controls as measured by the MOSSSS. Persons with MS displayed significantly lower scores on the overall social support index (t 238 = −1.98, P = .04) and on all functional subscales: emotional/informational support (t 238 = −2.30, P = .02), affective support (t 238 = −2.56, P = .01), and instrumental support (t 238 = −2.19, P = .03). No significant differences were observed between groups in the number of friends (t 238 = −0.51, P = .61) or family members (t 238 = 1.26, P = .21) (FIGURE).

Comparison of Social Support Scores Between Study Groups

Correlation analyses between social support measures and demographic and clinical variables for people with MS showed that the overall social support index and emotional/informational support and affectionate support subscales were associated with depression and fatigue measures (r = −0.37 to −0.17, P < .05). No statistically significant correlations were observed between social support and the remaining demographic and clinical variables. On the other hand, the overall index and all subscale scores for social support were associated with HRQOL (r = 0.18 to 0.49, P < .05) (TABLE S2).

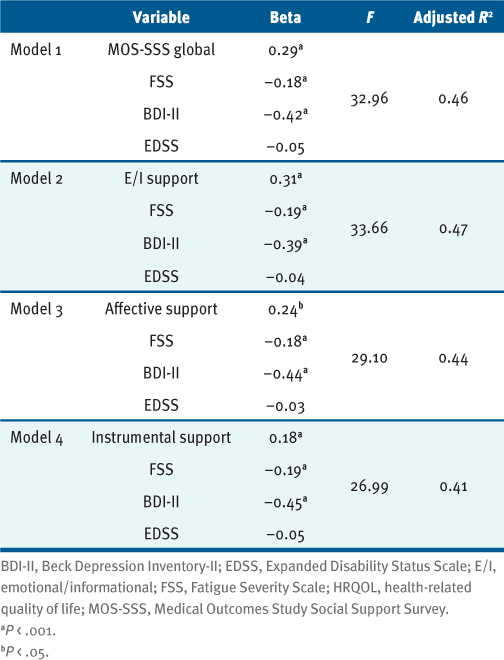

Multiple regression analyses showed that the 4 tested models contributed to HRQOL-explained variance (41%–47%); the emotional/informational social support model explained the most variance (47%). Fatigue and depression resulted in significant predictors in all models, as well as all social support scores. Global disability, as measured by the EDSS, was not a significant predictor of HRQOL (TABLE).

HRQOL Regressed on 4 Scores of Social Support, Fatigue, Depression, and EDSS

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to analyze perceived social support in persons with MS by studying related variables and analyzing their effect on quality of life. Comparisons between persons with MS and controls regarding perceived social support showed that persons with MS obtained significantly lower scores on the overall social support index and all the functional subscales on the MOS-SSS: emotional/informational support, affective support, and instrumental support. These results are in line with previous findings.33 Note that this study is the first to compare the performance of persons with MS and controls on the MOS-SSS, taking into account the functional and structural components of social support.16 Although there were no significant differences between groups in the number of friends or family members, it is important to highlight that the present study is the first to publish data on the structural components of the social support network as collected by the MOS-SSS. Many authors have studied different types of relationships (friends, family members, significant others, coworkers) that provide social support,14,19,34 but the number of people within the social support network has not been investigated. This work’s contribution proposes that although persons with MS rely on the same number of relationships for social support as individuals with no MS diagnosis, it is the quality of these relationships that seems to be affected in persons with MS.

Results indicate that persons with MS with higher depression and fatigue symptoms obtained lower scores on social support measures, both on the overall index and the 3 functional subscales. High levels of depression have already been associated with low social support,35 36 even in longitudinal studies such as that of de la Vega et al,37 in which persons with MS reporting reduced social support also presented with increased depressive symptoms at a 6-year follow-up visit. Other authors found this relationship only in persons with MS perceiving less support from their friends.14 A longitudinal study that followed a significant number of patients found that higher depression scores at baseline were associated with increases in reported levels of social support throughout the study, suggesting that persons with MS with higher depression scores may be recruiting more support over time as a means of coping.38 Regarding fatigue, similar findings have been reported in the literature: Persons with MS with greater social support also reported fewer fatigue symptoms.18 Other authors, however, did not find significant associations.14 Finally, although some research found a significant relationship between social support and physical disability,16 no such link was observed in the present study. This absence of correlation could be attributed to the small number of persons with high disability and progressive MS subtypes in the present sample.

These findings exhibit a strong association between perceived social support and several HRQOL dimensions. In addition, perceived social support proved to be a predictor of HRQOL. Among the different types of functional social support, emotional/informational support correlated the most with HRQOL, meaning that individuals who receive more suggestions and advice to anticipate and solve problems experience greater HRQOL. These results are in line with those of Costa et al,16 who also studied the MOS-SSS among persons with MS and found the same direct correlation with HRQOL. This study identifies psychological support as having the greatest effect on HRQOL; however, items on the MOS-SSS version used were grouped into 2 subscales, as opposed to the 3 functional subscales obtained by the factorial analysis of the MOS-SSS Argentine version. Other papers also described direct associations between HRQOL and social support,16 39 in which support provided by family members and friends was more related to the psychological HRQOL components and support offered by significant others was more related to the physical HRQOL components. Although this distinction could not be explored with the scale used in the present study, significant correlations were identified between the number of friends and family members in an individual’s social support network and the HRQOL global index as well as psychological well-being and illness symptoms. In this line, the friendship and family relationship dimensions of the HRQOL scale were associated with greater social support.

Limitations and Perspectives

The present study is cross-sectional: No causality can be inferred from the reported correlations. In addition, the sample was mostly composed of individuals with relapsing-remitting MS and low disability, limiting generalizability to all those with MS. It would be important to include patients with greater disability and progressive MS forms in future research considering that previous studies have shown that the extent of social support was more comprehensive in patients at advanced stages of the disease.40 Nonetheless, the present study underscores the importance of social support in the design of effective interventions aimed at improving quality of life for persons with MS. Interventions based on social support generally involve direct interaction with the person’s social environment, and the positive effects are the result of the resources that are exchanged during that interaction (ie, information, tangible help, companionship, emotional support, education). The challenge for the health professional lies, therefore, in the ability to adjust and enhance the resources of the environment of the person with MS to strengthen adherence to treatment and adequate coping with the disease.

CONCLUSIONS

Persons with MS perceive poor social support, which is associated with symptoms of depression and fatigue and predicts worse quality of life. Considering that adequate social support is a factor that has a protective or beneficial effect on multiple parameters related to health, it is necessary to assess this aspect in the daily treatment plan.

PRACTICE POINTS

Patients with multiple sclerosis obtained significantly lower perception of social support scores than controls.

Poorer social support is associated with poorer health-related quality of life.

It is important to consider the network and quality of social support to ensure more adequate treatment.

References

Bruchon-Schweitzer M, Boujut E. Psychologie de la santé: concepts, méthodes et modèles . 2nd ed. Dunod; 2014.

House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241(4865):540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889

Barrón A. Apoyo social: aspectos teóricos y aplicaciones. Siglo XXI; 1996.

Schaefer C, Coyne JC, Lazarus RS. The health-related functions of social support. J Behav Med. 1981;4(4):381–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00846149

Riquelme A. Depresión en residencies geriátricas: un studio empírico . Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Murcia; 1997.

Rodriguez Espíndola S, Enrique HC. Validación Argentina del Cuestionario MOS de Apoyo Social Percibido. Psicodebate. 2007;7(155):155–168. doi: 10.18682/pd.v7i0.433

Kruithof WJ, van Mierlo ML, Visser-Meily JM, van Heugten CM, Post MW. Associations between social support and stroke survivors’ health-related quality of life: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.003

Eshkoor SA, Hamid TA, Nudin SSH, Mun CY. The effects of social support, substance abuse and health care supports on life satisfaction in dementia. Soc Indic Res. 2014;116:535–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0304-0

Brownlee WJ, Hardy TA, Fazekas F, Miller DH. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1336–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30959-X

Campbell J, Rashid W, Cercignani M, Langdon D. Cognitive impairment among patients with multiple sclerosis: associations with employment and quality of life. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93(1097):143–147. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134071

Vanotti S, Eizaguirre MB, Ciufia NP, . Employment status monitoring in an Argentinian population of patients with multiple sclerosis: particularities of a developing country. Work. 2021;68(4):1121–1131. doi: 10.3233/WOR-213442

Hernández-Ledesma AL, Rodríguez-Méndez AJ, Gallardo-Vidal LS, Trejo-Cruz G, García-Solís P, Dávila-Esquivel FJ. Coping strategies and quality of life in Mexican multiple sclerosis patients: physical, psychological and social factors relationship. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;25:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.06.001

Freeman J, Gorst T, Gunn H, Robens S. “A non-person to the rest of the world”: experiences of social isolation amongst severely impaired people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(16):2295–2303. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1557267

Henry A, Tourbah A, Camus G, . Anxiety and depression in patients with multiple sclerosis: the mediating effects of perceived social support. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;27:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.09.039

Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. A review of psychological correlates of adjustment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(2):141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.12.001

Costa DC, Sá MJ, Calheiros JM. The effect of social support on the quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2012;70(2):108–113. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2012000200007

Mikula P, Timkova V, Linkova M, Vitkova M, Szilasiova J, Nagyova I. Fatigue and suicidal ideation in people with multiple sclerosis: the role of social support. Front Psychol. 2020;11:504. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00504

Aghaei N, Karbandi S, Gorji MA, Golkhatmi MB, Alizadeh B. Social support in relation to fatigue symptoms among patients with multiple sclerosis. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22(2):163–167. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.179610

Krokavcova M, van Dijk JP, Nagyova I, . Social support as a predictor of perceived health status in patients with multiple sclerosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(1):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.019

Rock DL, Green KE, Wise BK, Rock RD. Social support and social network scales: a psychometric review. Res Nurs Health . 1984;7(4):325–332. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770070411

D’Amico E, Haase R, Ziemssen T. Review: patient-reported outcomes in multiple sclerosis care. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;33:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.05.019

Khurana V, Sharma H, Afroz N, Callan A, Medin J. Patient-reported outcomes in multiple sclerosis: a systematic comparison of available measures. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(9):1099–1107. doi: 10.1111/ene.13339

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, . Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366

Vanotti S, Smerbeck A, Benedict RH, Caceres F. A new assessment tool for patients with multiple sclerosis from Spanish-speaking countries: validation of the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS (BICAMS) in Argentina. Clin Neuropsychol. 2016;30(7):1023–1031. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2016.1184317

Alonso RN, Eizaguirre MB, Silva B, . Brain function assessment of patients with multiple sclerosis in the Expanded Disability Status Scale: a proposal for modification. Int J MS Care. 2020;22(1):31–35. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2018-084

Allegri RF, Ollari JA, Mangone CA, . El “Mini Mental State Examination” en la Argentina: instrucciones para su administración. Rev Neurol Arg. 1999;24(1):31–35.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b

Simeoni M, Auquier P, Fernandez O, . Validation of the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life questionnaire. Mult Scler. 2008;14(2):219–230. doi: 10.1177/1352458507080733

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; 1996.

Brenlla ME, Rodriguez CM. Adaptación argentina del Inventario de Depresión de Beck. In: Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK, eds. BDI-II: Inventario de Depresión de Beck. 2nd ed. Paidos; 2006.

Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatiga y esclerosis múltiple (Boletín pautas de manejo clínico). Aznar V, Cáceres, F, Gold L, trans. Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444

Lorefice L, Fenu G, Frau J, Coghe G, Marrosu MG, Cocco E. The burden of multiple sclerosis and patients’ coping strategies. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018;8(1):38–40. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001324

Lorefice L, Mura G, Coni G, . What do multiple sclerosis patients and their caregivers perceive as unmet needs? BMC Neurol . 2013;13:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-177

Suh Y, Weikert M, Dlugonski D, Sandroff B, Motl RW. Physical activity, social support, and depression: possible independent and indirect associations in persons with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med. 2012;17(2):196–206. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.601747

Hyarat S, Al-Gamal E, Dela Rama E. Depression and perceived social support among Saudi patients with multiple sclerosis. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2018;54(3):428–435. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12293

de la Vega R, Molton IR, Miró J, Smith AE, Jensen MP. Changes in perceived social support predict changes in depressive symptoms in adults with physical disability. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(2):214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.09.005

Ratajska A, Glanz BI, Chitnis T, Weiner HL, Healy BC. Social support in multiple sclerosis: associations with quality of life, depression, and anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2020;138:110252. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110252

Costa DC, Sá MJ, Calheiros JM. Social support network and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017;75(5):267–271. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20170036

Rommer PS, Sühnel A, König N, Zettl UK. Coping with multiple sclerosis: the role of social support. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(1):11–16. doi: 10.1111/ane.12673

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: None.

PRIOR PRESENTATION: Preliminary data from this study were presented as a poster at the MSVirtual2020: 8th Joint ACTRIMS-ECTRIMS Meeting, September 11-13, 2020.