Practice Point

- The Distress Thermometer is a psychometrically sound tool that can be used in the clinical setting for screening of caregiver distress.

Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

From the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA (SLD, MP). Correspondence: Sara L. Douglas, PhD, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 44104, USA; email: SLD4@case.edu.

Background: Caregivers of persons with multiple sclerosis (MS) report high levels of distress. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT) is used extensively with patients with cancer and their caregivers but has not been tested in nononcology caregivers. The purpose of this study was to examine the psychometric properties and clinical utility of the barometer portion of the DT in caregivers of persons with MS.

Methods: A secondary analysis was performed of data from a randomized trial comparing the effectiveness of 2 interventions aimed at reducing psychological outcomes associated with caregiving. The DT and the 4-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Anxiety and Depression scales, which were administered at baseline, were used for all analyses. Construct validity (known groups) and convergent validity (interscale correlations) were evaluated. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was used to evaluate clinical diagnostic test evaluation.

Results: The DT had good construct validity supported by strong correlations for known-groups analyses and good convergent validity (r = 0.70–0.72). The DT also demonstrated good discrimination for anxiety (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.83) and depression (AUC = 0.80). The optimal screening cut point on the DT was 4 for anxiety and 5 for depression.

Conclusions: The barometer portion of the DT demonstrates good psychometric properties and clinical utility in caregivers of persons with MS. This is the first examination of the DT in MS care partners.

Psychological distress has been conceptualized as a “state of emotional suffering characterized by symptoms of anxiety and depression,”1,2 and research has demonstrated its effect not only on a patient’s quality of life but also on their adherence to treatment, satisfaction with care, and survival.3–5 Distress and negative emotional outcomes have also been documented in caregivers. Rates of distress and psychiatric disorders for caregivers have ranged from 15% to 60%,6 and caregiver distress has been shown to contribute to the delivery of lower-quality patient care and to poorer quality of life for the patient.5 Therefore, caregiver distress has been shown to impact not only the caregiver but also the patient.

To date, the most common tool used to measure distress in patients with cancer has been the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT).6–9 It has good psychometric properties and clinical utility in oncology care6,7 and consists of a visual analog scale (resembling a thermometer) that ranges from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress).8 There is also a list of 42 problems representing 5 different categories (practical, family, emotional, spiritual, physical) where individuals identify sources of distress from the list of problems. In the clinical setting, the single-item thermometer is often used to identify individuals who display elevated distress (score >4) and who should be referred for additional evaluation. The DT has high acceptability among patients, caregivers, and clinicians, primarily because of its brevity.1,6,7

In oncology, the DT is recommended as a quick screening measure to identify individuals with psychological distress who may present with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety.1,10,11 In addition, its use in the clinical setting is recommended because patients and caregivers do not stigmatize it like standard anxiety and depression tools.12 Finally, the DT is recommended because of the numerous validation studies (using depression and anxiety as reference measures)6,7,10,11 that have yielded cut points at which to make referrals for further psychological assessments.10,11

Although the DT has been used with some populations of patients without cancer, information about its psychometric properties and clinical utility with these populations is minimal.1 In a recent scoping review of the clinical utility of the DT for those without cancer,1 of the 53 studies identified, 37 included patients, 14 included parents of children with various illnesses, and only 2 included caregivers who were not parents of children with illness. Given the recognition of the important role that caregivers play in the support and care of all patients—especially those with long trajectories of care—there is a need to identify reliable and valid tools that can quickly identify elevated caregiver distress—especially in caregivers of nonchildren.

One such group is caregivers of persons with multiple sclerosis (MS); MS is a chronic demyelinating neurologic disorder that is often progressive in nature and results in problems with mobility and cognition as well as a variety of other physical and emotional outcomes.13 An estimated 46% to 58% of persons with MS receive informal, unpaid care not routinely provided through the established health care system over the course of their illness.13,14 Caregivers of persons with MS are reported to have low health-related quality of life and high levels of anxiety (68%), depression (44%), and distress (51%).13,14 As screening of cancer caregivers for distress has begun to be incorporated into outpatient clinics, MS caregivers should be screened as well, given the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and distress identified in this population, and health care providers should make referrals for further evaluation and treatment if needed.13,15 The first step in this process is to determine the psychometric properties and clinical utility of the DT for use in this caregiver population.

Baseline (prerandomization) data used for psychometric testing came from a randomized trial comparing the efficacy of 2 interventions aimed at reducing distress in caregivers of persons with MS.15 The study was conducted from April 2021 to February 2022 and included a national sample of MS caregivers. A caregiver was defined as someone (family or friend) who provides any type of support (eg, physical, emotional, or administrative support, such as paying bills) to the person with MS, who is not a professional caregiver, and who is not paid for their efforts.4,15 Convenience sampling was applied using social media and direct email to persons with MS who had participated in a previous study. Inclusion criteria for caregivers were as follows: (1) an adult family member or friend (≥18 years old) of a person with MS, (2) self-identified as an unpaid caregiver for a person with MS, (3) access to the internet, and (4) capable of providing informed consent in English. After initial screening, electronic informed consent was obtained using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture).16 Approval was obtained from Case Western Reserve’s institutional review board before data collection.

Distress was measured using the barometer portion of the DT.8 The barometer tool is a single-item, self-report measure of psychological distress and has excellent psychometric properties for both patients with cancer7,17 and their caregivers.6 Instructions for completion of the barometer tool defines distress as an “unpleasant experience of a mental, physical, social, or spiritual nature which can affect the way one thinks, feels, or acts.”8 Instructions also state that distress may make it harder to cope with disease, its symptoms, or its treatment.8 Individuals are asked to rate their distress in the past 7 days on an 11-point visual analog scale ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress), with higher scores indicating higher levels of distress.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves have demonstrated that the DT has good diagnostic utility for cancer caregivers relative to anxiety and depression reference measures.6 Area under the curve (AUC) analyses indicate that the DT has good overall discrimination (AUC = 0.85 for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System [PROMIS] Anxiety scale and AUC = 0.81 for the PROMIS Depression scale),6 and ROC curves also indicate that using a cut point of 4/5 maximizes sensitivity (86.2% Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]-Anxiety; 88.2% HADS-Depression) and specificity (71.2% HADS-Anxiety; 67.6% HADS-Depression).6 Scores of 4 or greater represent clinically elevated levels of distress for caregivers of those with cancer, and the DT is deemed appropriate to use as a clinical screening tool for patients with cancer and their caregivers.6

The PROMIS Anxiety and PROMIS Depression short-version instruments18,19 were used as reference measures for validation of the DT. Standardized anxiety and depression tools have been the most frequently used reference measures for validation of the DT in cancer populations.7 The PROMIS Anxiety instrument consists of 4 items, has a 7-day recall period, and uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores representing more anxiety severity. Raw scores are converted to standardized t scores for analysis using PROMIS guidelines (mean ± SD = 50 ± 10). General population cut points that classify scores as normal, mild, moderate, or severe anxiety have been validated.18 The short version has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in several patient populations,19,20 with good internal reliability (Cronbach α = 0.89–0.95)19,20 and good convergent validity (r = 0.71–0.79) between the PROMIS short version and other established measures of anxiety.20 In the present study, the Cronbach α for this scale at baseline was 0.85.

In previous research, ROC curve analyses demonstrated that the PROMIS Anxiety short version has good diagnostic utility in patients with pain and poststroke, with AUCs greater than 0.8020 and a cut point of 8 maximizing sensitivity (64.6%) and specificity (86.3%).20 Based on these studies, the PROMIS Anxiety short version has been deemed appropriate for use as a brief measure for screening patients for anxiety severity.19,20

The PROMIS Depression short-version instrument18 has the same number of items, recall period, and Likert scale as the PROMIS Anxiety short version, and t scores are converted using the same methods as outlined previously herein (mean ± SD = 50 ± 10), with higher scores indicating greater depression severity. General cut points that classify t scores as normal, mild, moderate, or severe depression have been validated.18 The short version has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in orthopedic outpatients and outpatients with musculoskeletal pain,19,20 with good internal reliability (Cronbach α = 0.89–0.93)20,21 and convergent validity reported.19,20 In the present study, baseline Cronbach α was 0.85.

In previous research, ROC curve analysis demonstrated that the PROMIS Depression short version has good diagnostic utility in patients with pain and poststroke, with AUCs greater than 0.80.19,20 Cut points of 8 have been shown to maximize sensitivity (89.8%) and specificity (79.5%).19 Based on this research, the PROMIS Depression short version has been deemed appropriate for use as a brief measure for screening patients for depression severity.18,19

After participant consent and before randomization, baseline data were collected remotely using REDCap. Baseline surveys included a demographic data form, the single-item DT tool, the PROMIS Anxiety short version, and the PROMIS Depression short version.

All data were checked and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28.0 (IBM Corp). The DT, PROMIS Anxiety, and PROMIS Depression t scores all followed a normal distribution as determined by Q-Q plots and 95% CIs around the mean skew and kurtosis values. All assumptions of test statistics were evaluated and met before the analyses were performed.

The known-groups approach was used to evaluate the construct validity of the DT.22 Participants were classified into 2 groups known to differ regarding their baseline depression and baseline anxiety (with the focal construct being distress). Because anxiety and depression were the reference measures for validation of the DT, we examined construct validity using both reference measures. Anxiety and depression scores were categorized (following PROMIS normed cut points) into normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe categories. Based on these baseline categories, we constructed 2 groups for anxiety and 2 groups for depression: those with scores categorized as “normal” and those with scores categorized as “severe” or “extremely severe.” We then compared the mean baseline DT scores for those 2 groups. These mean differences needed to be statistically significant in the expected direction for the instrument to be considered valid.22 We hypothesized that the mean DT scores for the 2 groups would differ significantly, with those in the “severe” or “extremely severe” category (anxiety, depression) having statistically significantly higher DT scores than those in the “normal” group.

Next, to evaluate convergent validity we tested the correlations between the focal measure (ie, the DT) and the measures of constructs with which conceptual convergence is expected. Previous validation studies for the DT have used measures of anxiety and depression in assessing convergent validity because research has shown strong relationships between the concepts of distress and anxiety and depression.12,19,20 Correlations less than 0.20 were considered low, 0.20 to 0.50 were considered moderate, and greater than 0.50 were considered large.23 It was hypothesized that there would be significant direct correlations between DT and each of the 2 PROMIS scales (anxiety, depression). To establish convergent validity, correlations needed to be statistically significant and demonstrate moderate to high correlations (≥0.45).22

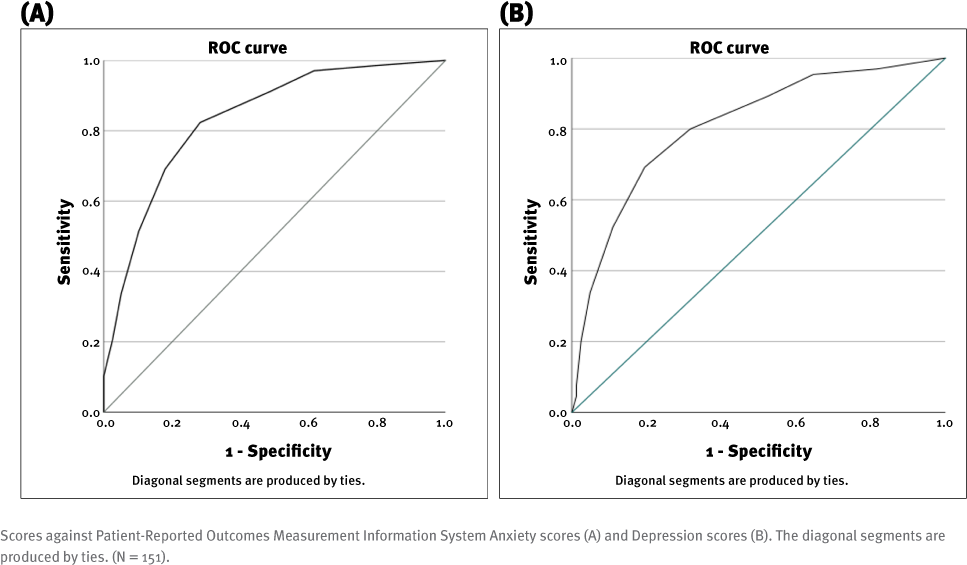

Given the general use of the DT in the clinical environment to screen individuals who need referral for treatment and management of elevated levels of distress,1,10,11 we also evaluated the diagnostic performance of the DT in a sample of caregivers of persons with MS. Using established, normed cut points for above-normal levels of anxiety and depression (for each PROMIS scale), we created dichotomous variables representing the standard criterion for presence or absence of anxiety and depression. The ROC curve analyses were conducted for each of the dichotomized PROMIS scales (anxiety, depression) against DT scores. The AUC values were examined to determine the validity of the DT as a diagnostic test for the PROMIS scales. The AUC values ranging from 0.90 to 1.0 indicated an excellent test, 0.80 to 0.89 a good test, 0.70 to 0.79 a fair test, 0.60 to 0.69 a poor test, and less than 0.60 a test of no diagnostic value.24 Finally, the best cut point DT score for each dichotomized PROMIS scale was determined by evaluating sensitivity, specificity, and Youden index scores for all values of the DT (0–10). The Youden index is a measure of a diagnostic test’s ability to balance sensitivity (detect disease) and specificity (detect no disease); values greater than 0.50 indicate a better-performing diagnostic test.20,25

There were 151 caregivers enrolled in the study who provided data at baseline. Caregivers were, on average, middle aged (mean ± SD age, 52.5 ± 13.9 years), White (n =134; 89.3%), and the spouse of the person with MS (n = 122; 80.8%%). Slightly more than half of the caregivers were female, and 53% had DT scores of 4 or greater (the cut point for caregivers of patients with cancer).6 Patients with MS, were, on average, female (65.6%) and middle aged (mean ± SD age, 50.3 ± 12.6 years), with a moderate level of disability (median Patient-Determined Disease Steps scale score = 4.0).

For construct validity evaluation, independent-samples t tests were used to examine known groups for anxiety and depression measures. Mean DT scores for those with PROMIS Anxiety t scores that were within normal limits (t scores <55) were compared with those that were moderate-severe (t scores >60). For anxiety, there was a significant difference in DT group means between the 2 groups (t 114 = 9.39; P < .001; r = 0.66). Those with anxiety within normal limits had a mean ± SD DT score of 2.54 ± 2.09 compared with a mean ± SD score of 6.56 ± 2.24 for those with moderate-severe anxiety. Next, mean DT scores for those with PROMIS Depression t scores that were within normal limits (t scores <55) were compared with those that were moderate-severe (t scores >60). There was a significant difference in DT group means between the 2 groups (t 112 = –8.61; P <.001; r = 0.63). Those with depression within normal limits had a mean ± SD DT score of 2.74 ± 2.18 compared with a mean ± SD score of 6.77 ± 2.25 for those with moderate-severe depression.

Correlations between DT, PROMIS Anxiety, and PROMIS Depression scores demonstrated strong and significant correlations (all with P < .001). Relationships were as follows: DT and PROMIS Anxiety (r = 0.72) and DT and PROMIS Depression (r = 0.70). These relationships demonstrate good convergent validity.

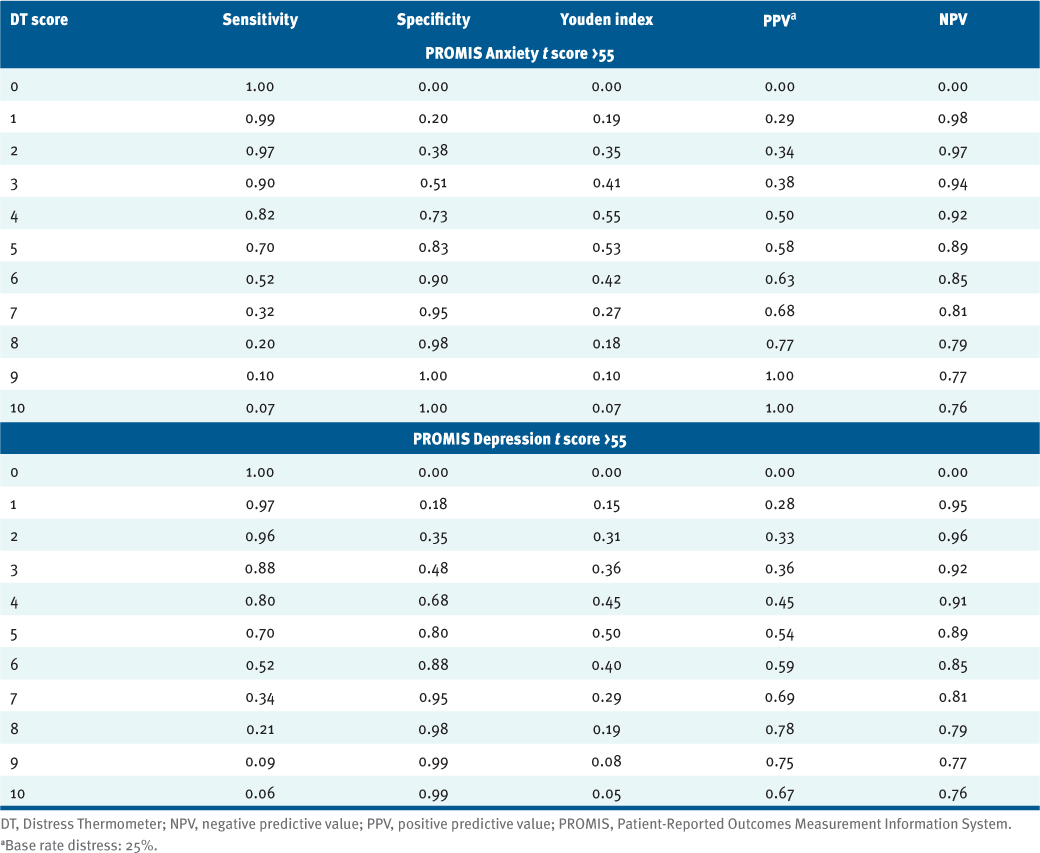

Established cut points for each PROMIS scale were used as the standard criteria for presence or absence of anxiety or depression. The ROC curve analysis against each criterion score revealed that the best DT cut point score for anxiety was 4 and for depression was 5. Both cut point scores yielded the highest Youden index. The Table displays the sensitivity, specificity, Youden index, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for all DT scores in each criterion. As seen in the Figure, the DT showed significant and strong discrimination, with an AUC of 0.83 (SE = 0.03; 95% CI, 0.77–0.90; P < .001) for PROMIS Anxiety and 0.80 (SE = 0.04; 95% CI, 0.73–0.87; P < .001) for PROMIS Depression.

Table. Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

Figure. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves for Distress Thermometer

This study provides initial preliminary psychometric findings regarding the DT in caregivers of persons with MS. First, the DT demonstrated strong convergent validity with other established criterion measures (PROMIS Anxiety and Depression scales), with all correlations exceeding the benchmark of 0.45 needed to demonstrate sufficient validity.22 In addition, the DT demonstrated an ability to discriminate between those with moderate-severe anxiety and depression and those with scores within normal limits. As hypothesized, mean differences were statistically significant, in the expected direction, and clinically significant with large effect sizes. Second, the AUCs indicate that the DT discriminates reasonably well between caregivers with and without anxiety and depression, with AUC values falling within the “good test” range.24 Finally, optimal screening cut points on the DT seem to be 4 for the anxiety measure and 5 for the depression measure. The cut points in the present sample varied from those recommended for caregivers of patients with chronic pain (cut point of 8 for anxiety and depression),20 caregivers of adolescents with schizophrenia (cut point of 7 for anxiety and depression),12 and caregivers of persons with cancer (cut point of 4).6 Given the variability of cut points by population, further research examining the psychometric properties of the DT for screening is needed. Psychometric testing should also be conducted in a larger sample of caregivers of persons with MS, a sample that has more variability in race, income, and relationship to persons with MS. Replication of the present findings will enhance confidence in recommending use of the DT for screening purposes and the cut points for anxiety and depression.

Although the need to assess distress in caregivers of persons with MS has been articulated,13,15 there are no reports of such screening being conducted in the outpatient setting to date. In the oncology outpatient (or chemotherapy infusion) setting, systematic distress screening of caregivers has been studied and implemented without difficulty.26 As with patients, caregivers with elevated DT scores are told of their findings and encouraged to meet with either the facility’s psycho-oncology services (eg, social workers, psychologists) or to meet with other psychosocial providers. In a recent study where this approach was used, 80% of caregivers were interested in meeting with the institutional psycho-oncology professional.26 This procedure is also feasible for caregivers of persons with MS. The DT, which takes 3 to 5 minutes to complete when incorporating the problem list,26 can be administered in the outpatient setting while waiting for an appointment with the patient’s physician. Either the physician or another health care provider can inform the caregiver when their distress score is elevated and provide contact information for professionals for further evaluation. Caregivers can share the information from the DT screening and problem list with current psychosocial professionals (if they have current therapists) or future professionals whom they see for further evaluation.

There are some areas of limitation in the present study. First, psychometric testing was applied solely to the DT barometer without including the list of problems. The original intent of the DT screening tool was to use both the barometer and the list of problems to identify not only those who have elevated distress scores but also the problems most related to their distress.1,8 In a scoping review of the clinical utility of the DT in nononcologic contexts1 it was noted that most studies (66%) in their review used the DT barometer only and did not include the problem list portion of the tool. The present study, similar to others, is limited in its ability to draw conclusions regarding the tool’s clinical utility because the entire tool was not tested. Future research evaluating the DT tool in a sample of caregivers of persons with MS should include the problem list component.

Second, no comprehensive testing regarding acceptability was conducted. Although few studies examining acceptability of the DT in populations of patients without cancer have been conducted,1 such testing can be very beneficial in terms of ensuring that the tool is clear and understandable to the individuals using it. The DT was originally designed for use with patients with cancer, and its extension into areas such as caregivers and patients without cancer means that it is possible that terminology or types of problems listed are not as relevant to those populations. Such testing and information could lead to modifications of the tool to include different types of problems on the problem list based on the intended population. It is recommended that future testing of the DT in caregivers for those without cancer include acceptability testing.

In summary, preliminary testing shows that the DT barometer is a valid measure of distress in caregivers of persons with MS and performs well as a screening tool for assessing those at risk for anxiety and/or depression. Based on the present findings, it is reasonable to use the DT barometer as a screening tool with caregivers of persons with MS and, given its brevity, is likely to have better clinical utility than longer validated measures. Additional testing of the full DT tool, including the problem list, in a more diverse sample is recommended to see whether these findings can be replicated. Given the importance of screening caregivers of persons with MS for psychological distress, use of the DT is reasonable, and further testing will potentially increase confidence in its use.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (grant MS-1610-37015-Enhancement).

Sousa H, Oliveira J, Figueiredo D, Ribeiro O. The clinical utility of the Distress Thermometer in non-oncological contexts: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(15–16):2131–2150. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15698

Drapeau A, Marchand A, Beaulieu-Prevost D. Epidemiology of psychological distress. In: L’Abate L, ed. Mental Illness: Understanding, Prediction and Control. IntechOpen; 2011:107–108.

Hamer M, Chida Y, Molloy GJ. Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(3):255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.11.002

Douglas SL, Mazanec P, Lipson AR, . Videoconference intervention for distance caregivers of patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(1):e26–e35. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00576

Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28(4):236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.006

Zwahlen D, Hagenbuch N, Carley MI, Recklitis CJ, Buchi S. Screening cancer patients’ families with the distress thermometer (DT): a validation study. Psychooncology. 2008;17(10):959–966. doi: 10.1002/pon.1320

Donovan KA, Grassi L, McGinty HL, Jacobsen PB. Validation of the distress thermometer worldwide: state of the science. Psychooncology. 2014;23(3):241–250. doi: 10.1002/pon.3430

Hoffman BM, Zevon MA, D’Arrigo MC, Cecchini TB. Screening for distress in cancer patients: the NCCN rapid-screening measure. Psychooncology. 2004;13(11):792–799. doi: 10.1002/pon.796

McElroy JA, Waindim F, Weston K, Wilson G. A systematic review of the translation and validation methods used for the National Comprehensive Cancer Network distress thermometer in non-English speaking countries. Psychooncology. 2022;31(8):1267–1274. doi: 10.1002/pon.5989

Graham-Wisener L, Dempster M, Sadler A, McCann L, McCorry NK. Validation of the Distress Thermometer in patients with advanced cancer receiving specialist palliative care in a hospice setting. Palliat Med. 2021;35(1):120–129. doi: 10.1177/0269216320954339

Kyranou M, Varvara C, Papathanasiou M, . Validation of the Greek version of the distress thermometer compared to the clinical interview for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):527. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02926-0

Bai X, Wang A, Cross W, . Validation of the distress thermometer for caregivers of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(2):687–698. doi: 10.1111/jan.14233

Maguire R, Maguire P. Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis: recent trends and future directions. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(7):18. doi: 10.1007/s11910-020-01043-5

Santos M, Sousa C, Pereira M, Pereira MG. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: a study with patients and caregivers. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(4):628–634. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.03.007

Douglas SL, Plow M, Packer T, Lipson AR, Lehman MJ. Psychoeducational interventions for caregivers of persons with multiple sclerosis: protocol for a randomized trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(8):e30617. doi: 10.2196/30617

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Cutillo A, O’Hea E, Person S, Lessard D, Harralson T, Boudreaux E. The distress thermometer: cutoff points and clinical use. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(3):329–336. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.329–336

Cella D, Choi SW, Condon DM, . PROMIS Adult Health Profiles: efficient short-form measures of seven health domains. Value Health. 2019;22(5):537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.02.004

Hung M, Stuart A, Cheng C, . Predicting the DRAM mZDI using the PROMIS anxiety and depression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(3):179–183. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000706

Kroenke K, Yu Z, Wu J, Kean J, Monahan PO. Operating characteristics of PROMIS four-item depression and anxiety scales in primary care patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1892–1901. doi: 10.1111/pme.12537

Kroenke K, Baye F, Lourens SG. Comparative responsiveness and minimally important difference of common anxiety measures. Med Care. 2019;57(11):890–897. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001185

DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, . A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(2):155–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x

Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences . 2nd ed. Routledge; 1988.

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Understanding diagnostic tests, part 3: receiver operating characteristic curves. Perspect Clin Res. 2018;9(3):145–148. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_87_18

Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3

Rajeshwari A, Revathi R, Prasad N, Michelle N. Assessment of distress among patients and primary caregivers: findings from a chemotherapy outpatient unit. Indian J Palliat Care. 2020;26(1):42–46. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_163_19