Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Projecting the Adequacy of the Multiple Sclerosis Neurologist Workforce

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Anecdotal reports suggest shortages among neurologists who provide multiple sclerosis (MS) patient care. However, little information is available regarding the current and future supply of and demand for this neurologist workforce.

Methods:

We used information from neurologist and neurology resident surveys, professional organizations, and previously reported studies to develop a model assessing the projected supply and demand (ie, expected physician visits) of neurologists providing MS patient care. Model projections extended through 2035.

Results:

The capacity for MS patient visits among the overall neurologist workforce is projected to increase by approximately 1% by 2025 and by 12% by 2035. However, the number of individuals with MS may increase at a greater rate, potentially resulting in decreased access to timely and high-quality care for this patient population. Shortages in the MS neurologist workforce may be particularly acute in small cities and rural areas. Based on model sensitivity analyses, potential strategies to substantially increase the capacity for MS physicians include increasing the number of patients with MS seen per neurologist, offering incentives to decrease neurologist retirement rates, and increasing the number of MS fellowship program positions.

Conclusions:

The neurologist workforce may be adequate for providing MS care currently, but shortages are projected over the next 2 decades. To help ensure access to needed care and support optimal outcomes among individuals with MS, policies and strategies to enhance the MS neurologist workforce must be explored now.

During the past several years, treatment options for individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) have expanded, including additional disease-modifying therapies (DMTs).1 2 Detailed knowledge about appropriate treatment options for patients with MS is largely limited to neurologists, and in particular to MS subspecialists. More than 90% of patients with MS indicated that they receive treatment and education from neurologists.3 Furthermore, receipt of treatment from neurologists is associated with a higher quality of care4 and a greater likelihood of receipt of DMTs.2

Reports of shortages among the overall neurologist workforce have existed for more than 3 decades.5 Dall et al.6 estimated that the demand for neurologists will significantly exceed the supply by 2025. Anecdotal evidence suggests an inadequate supply of MS subspecialists, with neurologists reporting difficulty in filling MS subspecialist positions and waiting lists for new patients and patient groups describing difficulties in finding available MS subspecialists. For this study, we developed a model to assess shortages in the current and future MS neurologist workforce. The model estimates the supply of neurologists and their capacity to provide MS patient care in 2015 to 2035.

Methods

Data Sources

We developed a model projecting the supply and demand of the MS neurologist workforce based on four types of data sources: 1) the MS Neurologist Workforce Study Surveys, involving neurology residents and neurologists; 2) a follow-up survey to neurology residency programs that offered MS fellowships in fall 2013; 3) survey results and other information provided by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME); and 4) peer-reviewed journal articles such as those by Brotherton and Etzel,7 Dall et al.,6 and Polsky.8 The logic diagram for the model is presented in Figure S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org.

Results from the MS Neurologist Workforce Study Surveys were the primary data sources for the model. More detailed information about the MS Neurologist Workforce Study Surveys appears in the articles by Halpern et al.9 10 and Kane et al.11 Briefly, these surveys collected information on exposure to individuals with MS during neurology training, interest in provision of care for patients with MS (among neurology residents), and current provision of care for patients with MS (among neurologists). The neurology resident survey also captured subsequent career plans, that is, interest in completing an MS fellowship, completing a neurology fellowship in a subspecialty area other than MS, or entering practice as a general neurologist. Information obtained from the neurologist survey also included the percentages of MS subspecialists, non-MS subspecialists (ie, neurologists specializing in areas other than MS), and general neurologists in clinical practice by practice location (urban/suburban vs. small city/rural), primary practice arrangement (solo/group practice vs. other practice setting), and age (categorized in quartiles). The neurologist survey findings also included plans to retire or to substantially reduce patient care hours in the near future and the average number of patients with MS per week seen by MS subspecialists, non-MS subspecialists, and general neurologists.

To supplement these surveys, we conducted a follow-up survey of neurology programs that offer an MS fellowship. The follow-up survey asked for 1) the number of MS fellowships available in the program for neurology residents or neurologists each year, 2) the current number of first-year MS fellows in the clinical or clinical/research program (ie, excluding research fellowships without a clinical focus), 3) the average number of neurology residents or neurologists completing the program's MS fellowship each year, 4) the average number of those completing the fellowship who practice as an MS subspecialist, and 5) the duration of the MS fellowship. We used the follow-up survey results to determine the number of available MS fellowship slots in the United States. Of those who expressed interest in MS subspecialty training in the MS Neurologist Workforce Neurology Resident Survey, we used the number of available MS fellowship slots from the follow-up survey to estimate the percentage of neurology residents who entered MS fellowship training. We also used the follow-up survey results to estimate the percentage of neurology residents completing MS fellowship training but not subsequently practicing as MS subspecialists.

The 2011 AAN resident survey provided the percentages of neurology residents interested in fellowship training.12 13 The ACGME provided data on the total number of neurology residents in the United States in 2012–2013. Brotherton and Etzel7 identified the percentage of neurology residents by program year. These data sources were used to determine the number of MS subspecialists, non-MS subspecialists, and general neurologists estimated to enter clinical practice by year.

We also used estimates from Dall et al.6 of the total number of neurologists in the United States and from Polsky8 of the number of child neurologists in the United States. The difference in these two estimates provided the total number of adult neurologists in the United States; the model projections include only adult neurologists who provide MS patient care.

To estimate the current number of MS subspecialist neurologists in the United States, we used data provided by the AAN on practicing neurologists who are members of the MS section. We classified as MS subspecialists neurologists who were members of this section and who selected only MS/neuroimmunology as a practice focus or selected MS/neuroimmunology and only one other area as a practice focus. We combined these data sources to determine the number of MS subspecialists, non-MS subspecialists, and general neurologists currently in clinical practice and the proportion of neurologists reducing or leaving clinical practice.

We modeled MS patient demand for outpatient visits with neurologists based on growth in the US population and assumed that MS prevalence would remain constant over time. Estimates indicate that 350,000 to 500,000 people in the United States have MS,14 although these estimates of MS prevalence vary widely.15–17 The average annual number of neurologist visits per individual with MS is unknown. Therefore, to project changes in demand over time for neurologist visits among persons with MS, we conservatively assumed that this demand, and the number of US individuals with MS, would increase at the same rate as the increase in the overall US population from 2015 to 2035.18

Tables S1 through S5 present parameters used in the workforce model based on the data sources and assumptions listed previously herein. Surveys conducted by study researchers were approved by the RTI International institutional review board (Research Triangle Park, NC). No contact or communications with patients occurred as part of the study.

MS Neurologist Workforce Model Development and Analyses

In the model, we provide projections for three groups of neurologists: MS subspecialists, non-MS subspecialists, and general neurologists (Table S6). To estimate the number of neurologists in practice each year (from 2015 to 2035), stratified by MS subspecialist status, the MS neurologist workforce model involves three components: 1) the number of neurology residents entering clinical practice each year as MS subspecialists, non-MS subspecialists, or general neurologists (ie, workforce input) (Table S1); 2) the number of neurologists in clinical practice at the start of the model period (2015) (ie, starting workforce size); and 3) the number of neurologists in clinical practice who retire or leave patient care each year (ie, workforce outflow), by MS subspecialist status and age group (Table S4). In addition, the model includes separate annual projections for the number of neurologists in each of these groups by practice location (urban/suburban vs. small city/rural), practice type (solo/group practice vs. other), and age group. For model projections regarding MS subspecialists, because of the small number of MS subspecialists in small city/rural locations, we could not stratify this group by practice type.

The capacity of the neurologist workforce to provide MS patient care is quantified as the projected number of available MS patient visits each week, calculated separately for MS subspecialists, non-MS subspecialists, and general neurologists (Tables S2 and S3). The annual number of MS patient visits is determined using the number of weeks per year of clinical practice by neurologists, stratified by MS subspecialist status and urban/rural location (Table S5).

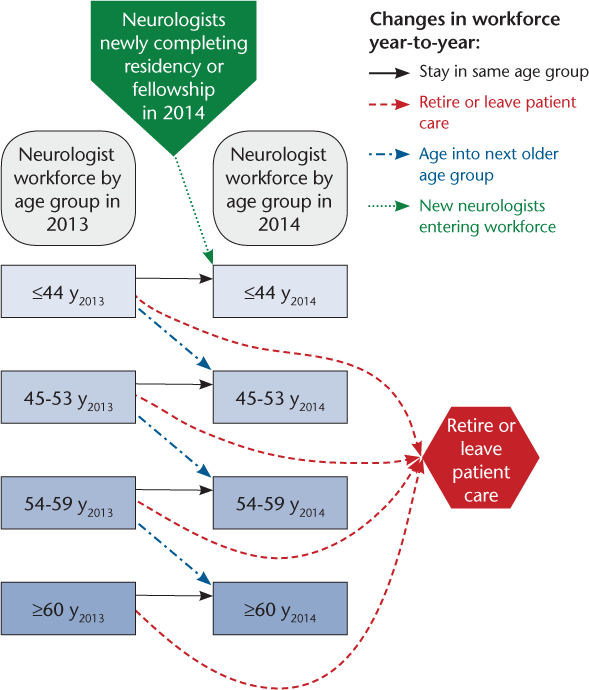

Summary model calculations are depicted in Figure 1. For 2014, the model workforce included neurologists who were in clinical practice in 2013 and remained in the same age group in 2014. Second, in each age category, the model removes neurologists who retired or significantly reduced patient care hours in 2014. Third, the model adjusts to account for neurologists who were in clinical practice in 2013 and were entering the next older age group in 2014. Finally, the model adds neurologists who were entering the workforce after completing their residency or fellowship in 2014, assuming that these neurologists entering the workforce were in the youngest age category. Similar calculations were performed to estimate the MS neurologist workforce for 2015 to 2035.

Multiple sclerosis neurologist workforce model schematic

Results

Model Projections

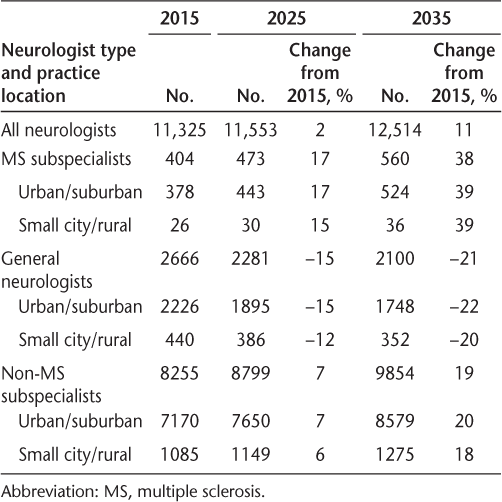

Table 1 presents the projected number of neurologists—overall, by MS subspecialist status, and by urban/rural practice location—for 2015, 2025, and 2035. In 2015, we estimate that there were 404 MS subspecialists (4% of the overall neurologist workforce), 2666 general neurologists (24%), and 8255 neurologists who are subspecialists in areas other than MS (73%). Small city/rural neurologists represent 6% of MS subspecialists, 17% of general neurologists, and 13% of non-MS subspecialists. By 2025, the overall number of neurologists is expected to increase only slightly (a 2% increase or 228 neurologists). The number of MS subspecialists is projected to increase by approximately 17%; however, this corresponds to an absolute increase of only 69 MS subspecialists between 2015 and 2025. The number of general neurologists is projected to decrease by 15% (386 neurologists) over this 10-year period, and the number of non-MS subspecialists is projected to increase by 7% (544 neurologists). For each group of neurologists, the proportion in the youngest age group (≤44 years) will increase substantially and the proportions in the older age groups will either remain approximately constant or decrease.

Projected number of neurologists, 2015–2035

By 2035, the total number of neurologists is expected to increase by 11% from 2015 (an increase of 1189 neurologists over 20 years). The numbers of MS subspecialists, general neurologists, and non-MS subspecialists are projected to increase by approximately 38% (n = 156), decrease by 21% (n = 566), and increase by 19% (n = 1599), respectively. In 2035, MS subspecialists will correspond to 5% of the neurologist workforce, general neurologists to 17%, and non-MS subspecialists to 79%.

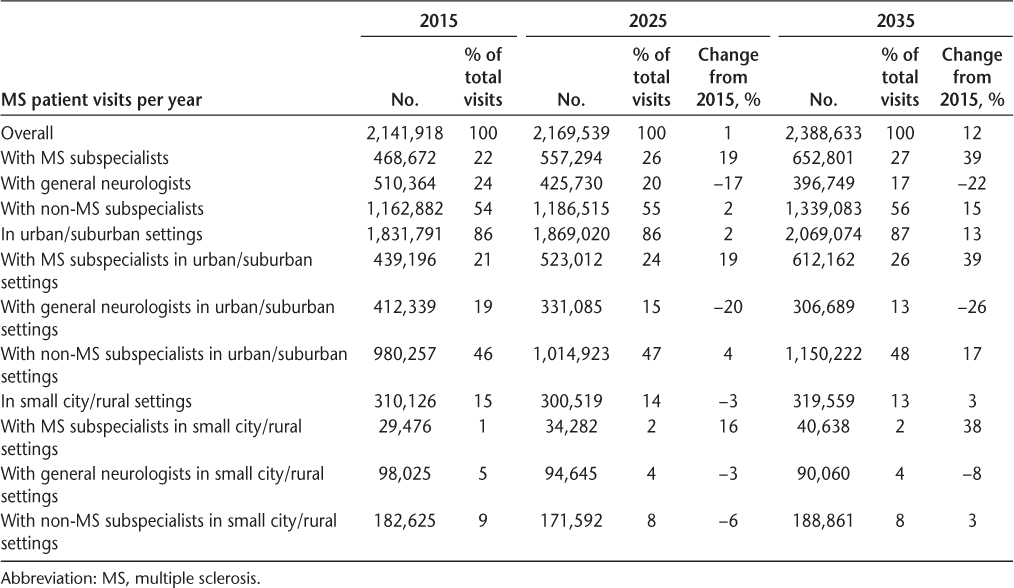

Based on the projected number of neurologists per year and the number of individuals with MS seen by each group of neurologists (Tables S2 and S3), we estimated the MS patient capacity of the neurologist workforce per year (ie, the maximum number of MS patient visits annually) for 2015, 2025, and 2035 (Table 2). In 2015, we projected that the neurologist workforce had capacity for approximately 2.14 million visits. Although MS subspecialists correspond to only 3.6% of the neurologist workforce in 2015, visits with MS subspecialists correspond to 22% of all MS patient visits. Visits with general neurologists correspond to 24% of MS patient visits, and 54% of visits were with non-MS subspecialists, the largest group of neurologists. Visits in urban practice locations accounted for 86% of all MS patient visits.

Projected capacity for MS patient visits per year

By 2025, the capacity for MS patient visits is projected to increase by 1% (approximately 27,600 visits per year). The proportion of visits with MS subspecialists increases by approximately 19%, and the proportion of visits with general neurologists decreases by 17%. The proportion of MS patient visits with non-MS subspecialists increases by 2% (23,600 visits per year). By 2035, the capacity for MS patient visits is projected to increase by 12% from 2015 (approximately 247,000 visits per year). The visit capacity among MS subspecialists increases by approximately 39% (184,000 visits per year); visits with general neurologists decrease by approximately 22% (n = 113,000), and visits with non-MS subspecialists increase by approximately 15% (n = 176,000) during this 20-year period. Visits in urban practice locations increase to account for approximately 87% of all MS patient visits.

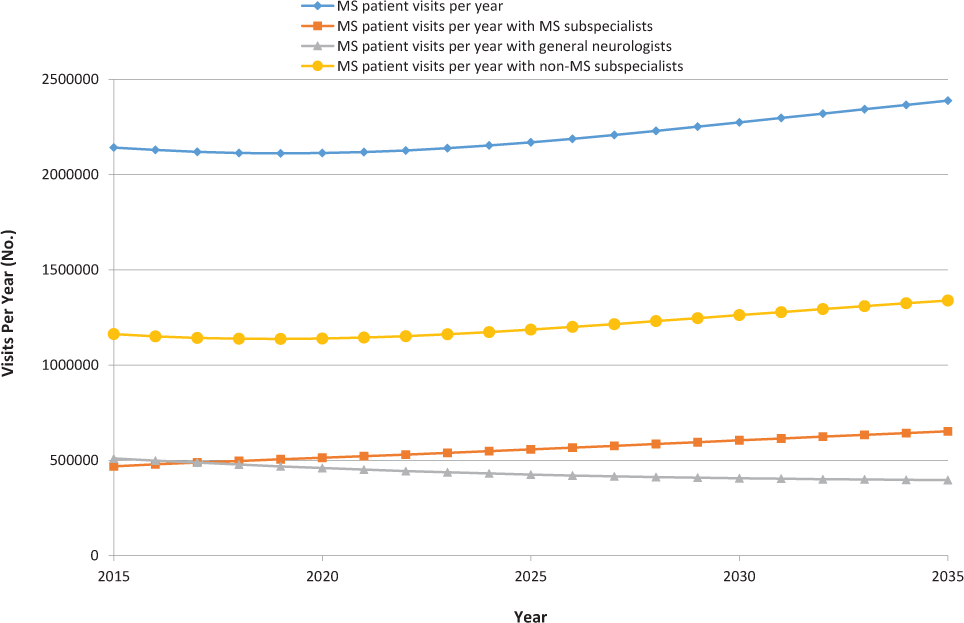

Figure 2 illustrates the annual capacity for MS patient visits. As presented in Table 2, the capacity for MS patient visits is projected to increase only slightly from 2015 to 2025, then to increase more rapidly from 2025 to 2035. Although the number of neurologists increases each year, the capacity of the neurologist workforce for MS patient visits decreases slightly (1%) for the first 5 years of the model (2015–2019). This reflects the change over time in the age distribution among neurologists as described previously herein; between 2015 and 2025, the proportion of neurologists 44 years or younger increases and the proportion older than 44 years decreases. Because older neurologists see more patients with MS per week than do younger neurologists, depending on the practice type and location (Tables S2 and S3), there is initially a small projected net decrease in the capacity of the neurologist workforce for MS patient visits. However, after these initial 5 years, the number of MS patient visits by the neurologist workforce increases for the remainder of the model. The change in the number of MS patient visits with non-MS subspecialists, which represents most MS patient visits each year, shows a similar change in the number of visits per year to that for the overall neurologist workforce. The capacity for MS patient visits with MS subspecialists increases fairly steadily over time, becoming greater than the total number of MS patient visits with general neurologists in 2017.

Projected capacity for multiple sclerosis (MS) patient visits by MS neurologist workforce over time

Sensitivity Analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess potential strategies to include the neurologist workforce capacity for MS patient visits. Tables S7 and S8 present results from these sensitivity analyses; in all the sensitivity analyses, the changes occur starting in 2015 and remain in effect through 2035. We explored the effects of the annual number of MS patient visits with neurologists (Table S7) and MS patient visits with MS subspecialists (Table S8) corresponding to a 20% increase in the number of MS fellowship positions, a 10% increase in the number of neurology residents, a 20% decrease in the adjusted retirement rate for MS subspecialists, a 20% decrease in the adjusted retirement rate for general neurologists and non-MS subspecialists, a 20% decrease in the adjusted retirement rate for neurologists, a 20% increase in the number of patients with MS seen by general neurologists, a 20% increase in the number of patients with MS seen by non-MS subspecialists, and 20% more new neurologists selecting practice locations in small city/rural locations (with the total number of neurologists and neurology residents remaining constant).

Sensitivity analyses indicate that increasing the number of patients with MS seen by non-MS subspecialists results in the greatest increase in MS patient visit capacity (Tables S7 and S8). Another strategy associated with substantial increases in the capacity for neurologist visits with individuals with MS is decreasing the retirement rate among neurologists. The most effective strategy for increasing the capacity for visits among MS subspecialists (Table S8) was increasing the number of MS fellowship positions. Increasing the proportion of neurologists who practice in small cities or rural areas does not substantially affect the overall capacity of the neurologist workforce for MS patient visits.

Discussion

Model projections for 2015 indicate that the capacity of the neurologist workforce in that year was approximately 2.1 million MS patient visits. Projection of current or future demand by persons with MS for neurologist visits is difficult because the current number of persons with MS in the United States is not known. As highlighted by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, “in the U.S., there has not been a scientifically sound, national study of prevalence since 1975. Additionally, MS incidence and prevalence are not consistently reported or tracked in the U.S.”19 Currently used estimates are 350,000 to 500,000 individuals with MS in the United States14; these estimates are likely low because a recently published study indicated more than 400,000 individuals with MS in the United States who have commercial insurance and did not include individuals with Medicare, Medicaid, or other forms of public insurance.20 Based on our projections of the capacity for neurologist visits, the 350,000 to 500,000 MS prevalence estimate corresponds to four to six neurologist visits per patient per year.

Although this estimate suggests that the overall MS neurologist workforce may currently be sufficient, several important considerations limit this conclusion. First, anecdotal reports suggest that approximately 50,000 patients with MS receive 13 visits for drug infusions per year. This corresponds to approximately 650,000 MS patient visits, although many of these visits likely are at infusion centers and may not directly involve neurologist care. The remaining 1.5 million neurologist visits per year correspond to only three to four neurologist visits per MS patient per year. Furthermore, the capacity of MS subspecialists to see individuals with MS is very limited. We estimate that in 2015, the MS subspecialist workforce had the capacity for approximately 470,000 MS patient visits, or approximately 1.3 visits per patient with MS. Given the crucial role of MS subspecialists in providing care for individuals with MS, particularly individuals with more advanced disease, this workforce is likely not sufficient for the needs of the MS patient population.

Because MS is a complex disease and emerging treatments require more intensive management, the demand for MS subspecialists may grow more quickly than currently estimated, and the shortage may become acute sooner. There may also be trends for general neurologists and non-MS specialists to be less willing to provide care for individuals with MS; younger neurologists, those in practice for shorter periods, and those who indicate that they lack sufficient knowledge for MS care see fewer patients with MS.10 This may further decrease the capacity for MS patient visits.

In addition, most of the MS neurologist workforce is located in urban/suburban areas. In small cities and rural areas, the workforce is limited; MS subspecialists in particular are highly limited in rural areas, suggesting that patients with MS will need to travel longer distances or receive care from other neurologists (such as general neurologists) who have a greater presence in small city/rural areas.

By 2025, the model projects that the number of US neurologists will grow by 2% and the capacity for MS patient visits with neurologists will grow by only 1%. In contrast, the US adult population is projected to grow by approximately 8.1% from 2015 to 2025.18 It seems likely that the MS neurologist workforce will not be adequate to provide needed care for individuals with MS within the next decade. By 2035, the neurologist workforce is projected to increase by 11% relative to 2015, and the capacity for MS patient visits is projected to increase by 12%. However, the US adult population is projected to grow by approximately 15%.18 Without changes in the medical care patterns for individuals with MS, there will likely be shortages in the neurologist workforce capacity for providing MS patient care for at least the next 20 years.

Sensitivity analyses indicate that increasing the number of patients with MS seen by non-MS subspecialists resulted in the greatest increase in total MS patient visit capacity (Tables S7 and S8). Non-MS subspecialists who lack sufficient knowledge to feel comfortable caring for patients with MS or who lack knowledge regarding newer DMTs see substantially fewer individuals with MS.9 Facilitating knowledge of current MS treatment patterns, including recently approved DMTs, among non-MS subspecialists, the largest group of neurologists, may substantially increase the capacity of the MS neurologist workforce.

The strategy with the second greatest effect on MS patient visit capacity is decreasing the retirement rate among neurologists. Among MS subspecialists, plans to retire were associated with lack of specialized personnel (nurses, social workers, etc.) for providing MS patient care.9 Providing additional personnel and other supports to assist with MS patient care may reduce physician burden and increase the likelihood of continuing in clinical practice, thereby decreasing projected shortages in the MS patient visit capacity. Greater involvement of advanced practice providers (eg, physician assistants and nurse practitioners) in MS patient care may also assist with this strategy.

The most effective strategy for increasing the capacity for visits among MS subspecialists was increasing the number of MS fellowship positions. Results from the neurology resident survey (discussed earlier herein) suggest that more residents are potentially interested in pursuing an MS fellowship than there are funded positions available.21 However, an ACGME-approved subspecialty certification for MS does not currently exist. This lack of institutional recognition may prevent neurology residents from considering an MS fellowship and decrease the likelihood for funding these fellowships. In addition, the neurologist survey indicated that among organizations seeking to hire a neurologist focused on MS care, mean time to hire such a neurologist was 16 months; this further indicates the need to increase the size of the MS subspecialist workforce.

One sensitivity analysis examined the effect on increasing the number of neurologists who choose to practice in a small city/rural environment. Individuals with MS living in small city/rural areas were more likely than their urban counterparts to have family medicine or general practice physicians rather than neurologists as their primary physicians, to travel farther to receive MS-focused care, to experience lower satisfaction with MS care, and to experience decreased health-related quality of life.4 22 Minden et al.2 found that although approximately one-third of patients with MS in urban locations had never used a DMT, 44% of those in rural areas had never used one. However, increasing the proportion of neurologists who practice in small cities/rural areas does not substantially affect the overall neurologist capacity for MS patient visits. Other strategies, such as greater use of telemedicine in the care of individuals with MS, may be necessary to address this rural/urban disparity.

There are several limitations of this study. As with any model, the projections of the MS neurologist workforce and the capacity for MS patient visits are only as robust as the data used to generate them. Given the diverse types of information needed for this model, we used data from a range of sources. Much of the data came from surveys of neurologists and neurology residents. All survey responses were obtained from self-report, and no attempt was made to validate responses. We included a broad population of neurologists and neurology residents in the surveys, but potential systematic biases in survey responses may affect model projections. In addition, baseline model parameters may change while the model is being constructed and analyzed. In particular, unexpected changes in factors such as the number of medical students entering neurology residencies, the number of neurology residents entering fellowship training, and the retirement rates among practicing neurologists would have substantial effects on model projections. In this model, we also assumed a constant enrollment in MS fellowships over time; however, that assumption rests on continued funding of such opportunities. Should funding decline, the projected 17% increase in MS subspecialists would also likely decline. In addition, we surveyed members of the AAN MS section to develop estimates; this could overestimate the number of MS subspecialists. However, we minimized this possibility by including only MS subspecialists who were actively engaged in patient care and who identified MS/neuroimmunology as their only neurologic specialty or as one of only two specialties.

Despite these potential limitations, this model provides important information for provision of care for individuals with MS. Although the capacity of the MS neurologist workforce currently seems to be adequate for individuals with MS, this will likely not be able to meet MS patient care needs starting in the next few years. Sensitivity analyses indicate a variety of strategies that may be useful to enhance the capacity for MS physicians to provide care for this patient population. In addition, increased involvement of advanced practice providers may also be helpful in ensuring timely and high-quality care for individuals with MS. In many MS clinical programs, advanced practice providers may already provide MS patient care. Future research should examine the role of advanced practice providers in MS care and how their involvement in MS care may be facilitated. Research is also needed on alternative care models for individuals with MS, such as collaborative care models and use of telemedicine to help meet MS patient needs in underserved regions. These results indicate current and potentially worsening future shortages in the MS neurologist workforce. There is an opportunity to conduct research and implement strategies to improve access to care for individuals with MS now, before greater shortages among health care professionals focused on MS develop.

PRACTICE POINTS

There are current shortages in the number of neurologists providing care for individuals with MS, and these shortages are projected to worsen in the future.

Strategies to address these shortages, such as greater involvement of advanced practice providers, increased MS fellowship opportunities, and supports to assist neurologists in providing MS care, must be explored to ensure high-quality and timely care for individuals with MS.

Financial Disclosures:

Dr. Giesser participated in an industry-sponsored clinical trial and received educational grant funding for a fellowship from Biogen. Dr. Johnson was a paid consultant for Teva and Questcor. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Bandari DS, Sternaman D, Chan T, Prostko CR, Sapir T. Evaluating risks, costs, and benefits of new and emerging therapies to optimize outcomes in multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18:1–17.

Minden SL, Hoaglin DC, Hadden L, Frankel D, Robbins T, Perloff J. Access to and utilization of neurologists by people with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;70(13 pt 2):1141–1149.

Kikaku America International. The multiple sclerosis trend report: perspectives from managed care, providers, and patients. https://secure.nationalmssociety.org/docs/HOM/ms_trend_report_full.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed May 19, 2016.

Buchanan RJ, Kaufman M, Zhu L, James W. Patient perceptions of multiple sclerosis-related care: comparisons by practice specialty of principal care physician. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008;23:267–272.

Dyken ML. The continuing undersupply of neurologists in the 1980s: impressions based on data from three studies. Neurology. 1982;32:651–656.

Dall TM, Storm MV, Chakrabarti R, et al. Supply and demand analysis of the current and future US neurology workforce. Neurology. 2013;81:470–478.

Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2012;308:2264–2279.

Polsky D. Child neurology: workforce and practice characteristics. LDI Issue Brief. 2005;10:1–4.

Halpern MT, Teixeira-Poit S, Kane HL, Frost AC, Keating M, Olmsted M. Interest in providing multiple sclerosis care and subspecializing in multiple sclerosis among neurology residents. Int J MS Care. 2014;16:26–38.

Halpern MT, Teixeira-Poit SM, Kane H, Frost C, Keating M, Olmsted M. Factors associated with neurologists' provision of MS patient care. Mult Scler Int. 2014;2014:624790.

Kane H, Halpern MT, Teixeira-Poit S, et al. Factors influencing interest in providing MS patient care among physiatry residents. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;35:89–95.

American Academy of Neurology. 2011 AAN resident survey final report. https://www.aan.com/uploadedFiles/Website_Library_Assets/Documents/8.Membership/1.Your_Membership/2.Member_Benefits/3.Residents_and_Fellows/2011%20AAN%20Resident%20Survey%20Final%20Report.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed March 30, 2016.

Freeman WD, Nolte CM, Matthews BR, Coleman M, Corboy JR. Results of the American Academy of Neurology resident survey. Neurology. 2011;76:e61–e67.

Multiple Sclerosis Foundation. Common questions: How many people have MS? https://msfocus.org/Get-Educated/Common-Questions.Accessed August 31, 2016.

Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn-Hardy K, Mohamed M, Chaudhuri AR, Zalutsky R. How common are the “common” neurologic disorders? Neurology. 2007;68:326–337.

Noonan CW, Williamson DM, Henry JP, et al. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in 3 US communities. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7:A12.

Williamson DM, Henry JP, Schiffer R, Wagner L. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in 19 Texas counties, 1998–2000. J Environ Health. 2007;69:41–45.

US Census Bureau. 2014 national population projections: summary tables. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html. Published 2015. Accessed August 31, 2016.

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. MS prevalence. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/About-the-Society/MS-Prevalence. Accessed August 31, 2016.

Dilokthornsakul P, Valuck RJ, Nair KV, Corboy JR, Allen RR, Campbell JD. Multiple sclerosis prevalence in the United States commercially insured population. Neurology. 2016;86:1014–1021.

Cahill C. An analysis of how neurology trainees select neurology fellowships. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology; April 2016; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Buchanan RJ, Wang S, Stuifbergen A, Chakravorty BJ, Zhu L, Kim M. Urban/rural differences in the use of physician services by people with multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation. 2006;21:177–187.