Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Patient Satisfaction with Physicians and Nurse Practitioners in Multiple Sclerosis Centers

Abstract

Background:

With the predicted shortage of neurologists, care of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) may be affected. Nurse practitioners (NPs) have successfully filled the provider gaps in a variety of care settings, with positive effects on care outcomes, including patient satisfaction. The purpose of this study was to determine patient satisfaction with physicians (MDs) and NPs in MS centers.

Methods:

This is a cross-sectional pilot study wherein a convenience sample was recruited from two MS centers. Demographic data were collected previsit, and satisfaction surveys were completed postvisit using the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18) and the Visit-Specific Satisfaction Instrument (VSQ-9). Different attributes of satisfaction and visit times were analyzed.

Results:

Patient satisfaction with both types of providers was high. All attributes of satisfaction were comparable for NPs and MDs, and they spent similar amounts of time with their patients, often exceeding the scheduled office visit duration. Encounter length was a strong determinant of patient satisfaction: VSQ-9 scores were significantly lower (P = .01) when duration was less than 20 minutes. Satisfaction was higher (P = .011) in patients who were diagnosed as having MS for 10 years or longer or had progressive MS, irrespective of provider type.

Conclusions:

This pilot study showed that use of standardized questionnaires to determine patient satisfaction with NPs and MDs was feasible. With the impending neurologist shortage and the increased MS prevalence, a collaborative team approach between NPs and MDs may improve access to care in MS centers without compromising patient satisfaction.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common disabling neurologic disease of young adults, characterized by occasional acute flare-ups requiring frequent medical monitoring and interventions.1 An estimated 1 million people in the United States are affected by this disease, which has an unpredictable course.2 The National MS Society has established the Partners in MS Care Program, which refers to “health care providers who have demonstrated knowledge and expertise in treating patients with MS.” This program includes the MS Centers for Comprehensive Care, which have been established to provide multidisciplinary, comprehensive care for the MS population.3 Anecdotal evidence from patient groups suggests that persons with MS can have difficulty in gaining access to appropriate care from neurologists and that there are substantial wait times for new patients to see MS physician (MD) specialists.4 This may be compounded by a projected decrease in neurologists. A report by the Workforce Task Force of the American Academy of Neurology estimates that there will be a 19% shortfall in the supply of neurologists by 2025.5 Halpern et al4 found that there will likely be shortages in neurologists and the MS workforce within the next decade. Nurse practitioners (NPs) trained in neurology and MS care may need to be called on to provide the essential comprehensive care to this population, thereby improving access.

Treating and managing relapses, modifying the course of disease, managing symptoms, and improving health-related quality of life fall within the scope of NP practice.6 Yet NPs are not universally employed by MS clinics. Nurse practitioners are licensed by their state Board of Nursing to evaluate, diagnose, order and interpret diagnostic tests, and initiate and manage treatments, including prescribing medications and controlled substances.7,8 Although states may differ in some regulations, in many areas NPs are the primary MS care providers for patients.

An important metric of the quality of care provided by NPs can be measured by patient satisfaction surveys. Patient satisfaction has been used as a surrogate marker for quality and value of health care delivery in hospitals and outpatient clinics.9 Evaluating patient satisfaction is clinically relevant because satisfied patients are more likely to comply with treatment, actively participate in care, and return to the same provider. Contrary to this, unsatisfied patients have been shown to have poorer clinical outcomes.10 . 11 Patient–provider interaction and support for patient self-management have been shown to have a direct positive effect on satisfaction of patients with chronic illness.12

As advanced care providers, NPs have successfully filled the provider gap in a variety of care settings without compromising patient care outcomes, including satisfaction with care.11–14 Chronic illness management studies comparing providers revealed similar or higher satisfaction with NPs or a team (MD+NP) approach.12 Equivalent or better satisfaction with NPs compared with MDs was noted in various care settings.15,16 Equal or improved patient satisfaction with NPs compared with MDs and physician assistants (PAs) was evidenced by nationally run surveys. A Veteran's Health Administration survey of 1,601,828 patients revealed that the satisfaction scores increased by 5% when the number of NPs was increased. Comparatively, when the number of MDs was increased, the satisfaction scores increased by 1.8%, and when the number of PAs was increased, the scores slightly increased or stayed the same. Most of the primary care clinic patients preferred to see NPs versus PAs and MDs.17 Medicare surveyed 146,880 beneficiaries and found that the patient satisfaction results were similar across the three providers.18

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews also reported positive effects of NP-led care on patient satisfaction, both nationally and internationally.19,20 Health outcomes were similar for NPs and MDs in primary care settings. In fact, nurse-led care had a positive effect on patient satisfaction.19 Positive effects on patient satisfaction by NPs were attributed to longer consultation times, giving more information to patients, and re-calling patients more frequently than MDs.16 Kurtzman and Barnow21 compared quality and practice patterns of NPs and PAs versus primary care MDs in patients receiving care from health centers across the United States. Results showed that there were no statistically significant differences in NP or PA care compared with primary care MD care. In fact, patients seen by NPs were more likely to receive smoking cessation advice, and both NPs and PAs were more likely to spend time teaching health promotion and prevention than were MDs. As care across the life span becomes more complex, NPs are being employed in many specialty areas.

Advances in MS treatment during the past 2 decades have led to the demand for highly skilled providers to meet the needs of patients across the disease course.22 With the advanced training they receive, NPs can treat and manage relapses, modify the course of disease, manage symptoms, and help improve health-related quality of life, similar to in other chronic diseases.7 Unlike registered nurses, NPs assume an independent provider role with the key attributes of autonomy and leadership, which equip them to meet the physical, psychological, educational, and spiritual needs of this population.22 In MS centers, the NP has carried the role of an administrator, educator, consultant, collaborator, researcher, and advocate in addition to being an expert clinician. Their clinical practice models vary from independent to collaborative to a team (MD+NP) approach in MS centers. It is vital to examine satisfaction with NP care in MS centers when newer models of provision of care are advocated. The purpose of this study is to compare patient satisfaction with NPs and MDs during outpatient visits in MS centers and to explore clinical and visit-related correlates of patient satisfaction.

Methods

A cross-sectional comparative design was used for this pilot study. Adult patients from two MS centers on Long Island, New York, were selected because both employed MDs and NPs who were specialists in MS care. Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained from both MS centers. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of recruitment, and anonymity was ensured. At the time of their outpatient visit, patients were requested to complete demographic, patient satisfaction, and visit-specific questionnaires. Scheduled office visit time for established patients with each practitioner and patient-perceived visit time were also obtained.

Sample

A self-selected convenience sample of patients interested in participating was recruited into the study. To be included, participants had to have a diagnosis of any type of MS, been a patient with the same practice for at least 2 years, and been evaluated by both MDs and NPs in different office visits.

Survey Instruments

The survey instruments used were the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18) and the Visit-Specific Satisfaction Instrument (VSQ-9). Both instruments are public documents and are available without charge.

The PSQ-18 was developed in 1994 by Marshall and Hays.23 This scale has an acceptable internal consistency reliability (Cronbach alpha of the subscales, 0.64–0.77) and high correlations with the overall patterns of the newest longer version, PSQ-III.23 For this study, the short survey was selected for convenience and feasibility. The PSQ-18 takes 3 to 4 minutes to complete and measures six aspects of care: technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with the provider, and accessibility.23 The scale was modified for this study by replacing the word doctor with provider.

The VSQ-9 is a 9-item visit-specific satisfaction questionnaire adapted by the American Medical Group Association from the Visit Rating Questionnaire used in the Medical Outcomes Study, a 2-year study of patients with chronic conditions. This tool rates the provider's technical skills (thoroughness, carefulness, competence), personal manner (courtesy, respect, sensitivity, and friendliness), and explanations of what was done, as well as time spent during the visit, the appointment wait time, the office wait time, the convenience of the office location, and telephone access.24

Procedure

Providers and patients from two National MS Society Centers for Comprehensive Care and designated Partners in MS Care were recruited for this study. Each center sees approximately 2000 patients with MS yearly and offers a full array of medical, psychosocial, and rehabilitation services required for complete care of patients with MS. Center 1 has two MS specialty MDs and one MS-certified NP, and center 2 has three MS specialty MDs and three MS-certified NPs. The NPs and MDs see patients independently, and patients are advised to see both providers annually. Both centers are accessible, include multiple disciplines, have numerous support staff designated for MS providers and patients, and are well-known in the region. Data collection was completed over 6 months on specific “MS days” in each center. Those days were Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday in center 1 and Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday in center 2. During data collection on those MS days, all the providers were in the centers, ensuring that each provider had patients who participated in the study. The total number of days of data collection was 18. To limit selection bias, all patients with MS who came to the center on the data collection days were offered the survey and then screened for inclusion. The first 30 patients who met the criteria in each center and completed informed consent forms for the study were surveyed. Demographic data were collected, including patient age, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity, educational level, type of MS, disease duration (number of years with diagnosis), and number of years with the practice. Patients completed the PSQ-18 and the VSQ-9 immediately after the visit. Scheduled office visit time for the appointment with each practitioner and the patient-perceived visit time were also obtained immediately after the visit. The scheduled office visit time referred to the specific amount of time, in minutes, that each provider was given for any visit with any person with MS. This varied depending on the center; MDs were scheduled for 15 or 20 minutes per visit and NPs were scheduled for 20 or 30 minutes. Patient-perceived time referred to the time, in minutes, that the patient believed they spent with the provider. Actual time spent with the provider was not obtained.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). The data were examined for missing variables and data entry errors both manually and using IBM SPSS. No imputation was implemented for missing data. Sample characteristics were described using descriptive statistics. The PSQ-18 and the VSQ-9 are Likert-type scales and were coded and categorized based on the scoring directions. The attributes of patient satisfaction, such as general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with the provider, and accessibility and convenience, were averaged and scored based on the tool directions. To score the VSQ-9, the responses from each individual were transformed linearly to a 0 to 100 scale, with 100 corresponding to excellent and 0 corresponding to poor. Responses to the nine VSQ-9 items were then averaged together to create a VSQ-9 score for each person.

Categorical variables (eg, demographic measures) were evaluated by frequency distribution and χ2 tests. Variables measured using Likert scale ratings (the PSQ-18 and the VSQ-9) were analyzed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests because the data were measured using an ordinal scale rather than a ratio scale. Scores are presented as median or mode rather than as mean or SDs.

The two groups of patients—those who saw an MD and those who saw an NP—were compared for each attribute of the PSQ-18. The level of significance for all statistical testing was set at P = .05.

Results

Sixty surveys were collected and analyzed: 30 from patients who were seen by an MD and 30 from patients who were seen by an NP. Visual inspection of frequency distribution of the satisfaction ratings showed the data to be skewed toward higher satisfaction ratings. In fact, 87% of the scores on the PSQ-18 were rated as 4 (satisfied) or 5 (highly satisfied), and the mean of the VSQ-9 scores was 81%.

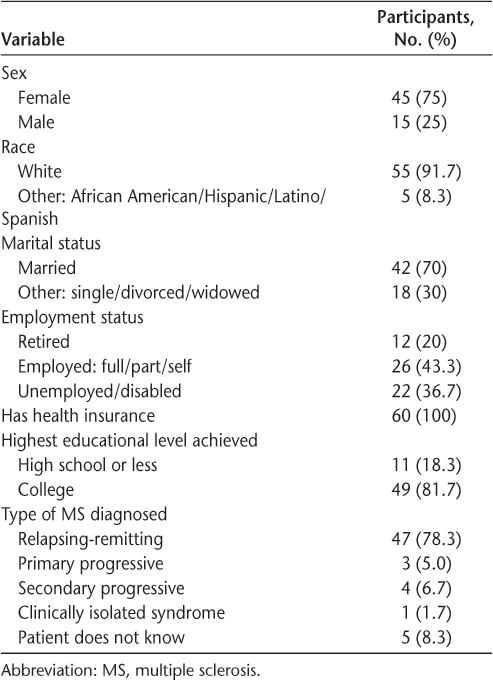

For purposes of analysis, demographic data were recoded to create two groups of approximately equal size, where possible, for each variable. Race was recoded into white (n = 55 [91.7%]) versus other (n = 5 [8.3%]). Marital status was recoded to separate married respondents (n = 42 [70.0%]) from single, divorced, and widowed patients (n = 18 [30.0%]). Employment status was recategorized to compare employed patients (full-time, part-time, or self-employed) (n = 26 [43.3%]), retired patients (n = 12 [20%]), and those who were unemployed or on disability (n = 22 [36.7%]). Educational level was collapsed to contrast patients with high school or less (n = 11 [18.3%]) and those with any college (n = 49 [81.7%]). All 60 patients had health insurance, and the copayment at the visit ranged from $0 to $60 (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 60 study participants

Clinical attributes were also recoded. Type of MS was categorized into progressive type, which included primary and secondary progressive types (n = 7 [11.7%]), and nonprogressive type, which consisted of relapsing-remitting variety and clinically isolated syndrome (n = 48 [80.0%]). Five patients (8.3%) reported that they did not know their disease type and, therefore, could not be categorized. Disease duration (time since diagnosis) ranged from 2 to 35 years. Time with the current practice ranged from 2 to 30 years (Table 2).

Participant features and average VSQ-9 score

The PSQ-18 scores were compared using a Mann-Whitney U test. Most scores for MDs ranged from 4.5 to 5.0 and for NPs from 4.0 to 5.0. There was no significant difference in any of the attributes of satisfaction between the two groups: general satisfaction (P = .07), technical quality (P = .25), interpersonal manner (P = .42), communication (P = .23), financial aspects (P = .15), and accessibility and convenience (P = .98). Visit satisfaction based on VSQ-9 scores was also equal (P = .97). Although the difference in time spent with the provider was a PSQ-18 satisfaction attribute that approached significance (P = .053), the actual difference between median times was negligible (approximately 0.025).

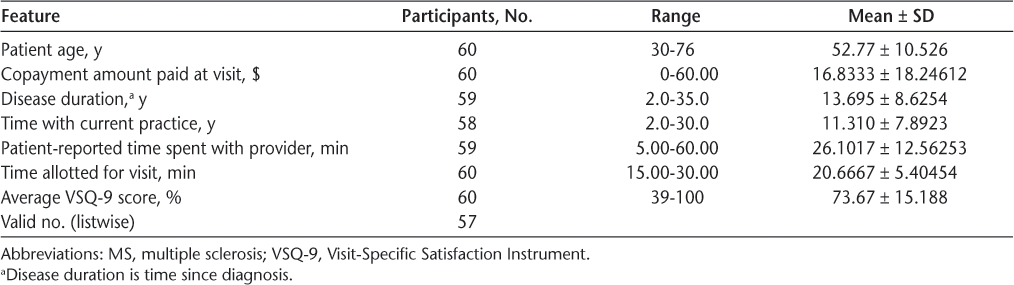

On analyzing all satisfaction attributes based on disease duration (time since diagnosis), patients with a longer disease duration (≥10 years) were more satisfied on the VSQ-9 average irrespective of the type of provider (P = .011) (Figure 1). Satisfaction attributes were also compared based on nonprogressive type and progressive type of MS course. A significant difference in the attribute of accessibility and convenience was noted (P = .029). The small group of progressive type reported higher satisfaction in this attribute.

Average Visit-Specific Satisfaction Instrument (VSQ-9) scores compared by disease duration

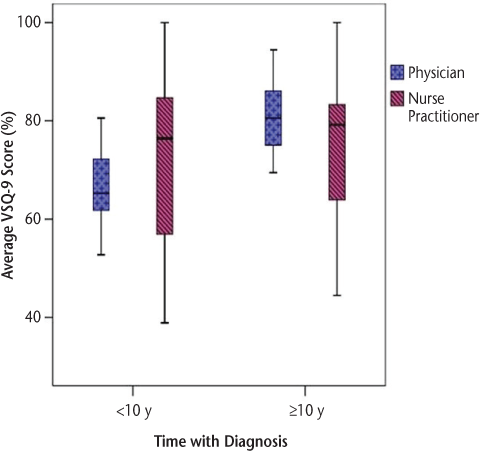

The patient-reported visit time was also noted to have an influence on visit satisfaction as measured by the VSQ-9 scores. Average visit time was 26 minutes for MDs and 27 minutes for NPs, but this was not significant (P = .69). Eighty-eight percent of the providers spent 20 minutes or more with their patients despite that at one practice all MD and some NP encounters were allotted only 15 minutes. Fifty percent of the providers spent 25 minutes or more with the patient. Looking at the wide range of time spent (5–60 minutes), and high satisfaction scores (mean VSQ-9 score, 74), it can be inferred that MS providers tend to spend enough time with the patient based on their needs. But there was a significant difference in VSQ-9 scores when providers spent less than 20 minutes (P = .01). This difference was similarly significant in both types of providers (Figure 2).

Average Visit-Specific Satisfaction Instrument (VSQ-9) scores compared by patient-reported time in visit

Discussion

This pilot study is likely the first study evaluating patient satisfaction with NPs and MDs in the neurology outpatient clinic. It represents a fundamental phase of the research process to evaluate patient satisfaction related to provider discipline. The purpose of conducting this pilot study was to examine the feasibility of an approach intended for use in a needed larger study. We compared patient satisfaction with MDs and NPs in two MS centers in a suburban area and found no differences. Both provider groups scored high in all attributes of satisfaction.

The findings of this pilot study are preliminary and need further studies to validate them; however, initial findings suggest comparable satisfaction scores regardless of type of provider (NP or MD) in established patients at MS centers. They should also be interpreted with caution due to the small numbers of patients and providers. We showed that there were no significant differences in any of the attributes of patient satisfaction measured by the two surveys, such as general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, accessibility and convenience, and time spent with provider (not quantitative) between the patients seen by the MD versus the NP. The visit-specific satisfaction scores measured by the VSQ-9 were also not different. In the study by Taylor25 of patient satisfaction in the primary care setting in rural Texas, NPs scored higher than MDs in all the PSQ-18 subscales. This finding may be related to the rural setting, where provider accessibility is different compared with suburban areas.

One visit-related attribute evaluated by this study was patient-reported visit time and was found not to be different. Most practitioners averaged 20 minutes, and visit satisfaction with provider significantly differed if it was less than 20 minutes. Thus, it can be inferred that the practitioners spent enough time with each patient based on their need. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Community Health Center data (2006–2010) found that the time spent per patient was similar for MDs, NPs, and PAs.26 A study conducted in an orthopedic surgery spine clinic concluded that patient-perceived adequate time with the provider resulted in a nearly 60% increase in Press Ganey overall satisfaction score.27 Another study noted “greater satisfaction with time spent for visits longer than 15 minutes but with less satisfaction with time spent for shorter visits.”28(p133) However, it needs to be emphasized that the patient-reported time may be different from the actual time spent with the provider and that most patients underestimate the time of consultations.29

This pilot study did not examine any of the specific provider attributes in relation to the satisfaction attributes. However, some of the previous studies focusing on patient satisfaction attributed the high satisfaction with NPs to the type of training they receive.15,25 In addition, Budzi et al17 associated the high ratings to “paying attention to patient's educational needs and providing for that need, giving individualized care and active listening”(p174) by the NPs. Further studies are needed that focus on provider attributes contributing to patient satisfaction.

The patient-specific factors that were noted to be associated with satisfaction are the duration and type of MS. Patients with disease duration of 10 years or more were more satisfied. Although health status is known to affect satisfaction with care,29 this particular effect cannot be explained based on the current literature because MS has a very dynamic course. However, in a study in primary care settings, Fan et al30 found that longer length of time with the provider is associated with increased patient satisfaction and greater adherence to medical advice.

Patients with a progressive course of MS reported improved scores in accessibility and convenience, which also could not be explained based on the current literature. The progressive type group had a small sample size yet the difference in this attribute was statistically significant. This may be a limitation of this study in that it may reflect satisfaction with the MS center as an organization and less for the individual provider. However, it may be difficult to untangle the provider from the organization because many patients have no clinical expertise and may be influenced by nonmedical factors. Thus, if the patient is not satisfied with the office, they are more likely not to be satisfied with the provider.31

The findings from this pilot study combined with other larger study findings support the role of NPs in the care of chronically ill patients. This study added to the general literature and focused on patient satisfaction with NPs and MDs who provide care to patients with MS. Access to MS MDs and continuity of care for patients may be reduced as the shortage of neurologists increases. The use of NPs (and PAs) can be crucial in improving access to MS providers and enhancing quality of care.32 Advanced care practitioners such as NPs and PAs have been shown to be successful in improving access to care in primary care settings and in many outpatient specialty medical practices, reducing wait time and improving quality of care.33 Loretta Ford and Henry Silver developed the NP role 50 years ago due to the demand for primary care services and nursing's potential to meet the need in the setting of physician shortage.34 As NPs successfully filled the gap in various care settings ranging from primary care to specialty care, outpatient to acute care, MS centers can successfully develop a cost-effective quality care model by adding more NPs in their care teams.

This preliminary study has several other limitations. First, it was designed to be a pilot study involving only two MS centers. Owing to this pilot study's small sample, associations between provider type and patient satisfaction must be interpreted with caution and limits the generalizability of the study.

This pilot study was not a hypothesis-testing study, it was an exploratory study. It was supported by evidence that suggested that patient satisfaction may be related to provider discipline. It did not include a power analysis because it was not designed to detect a clinically meaningful difference with the specified inferential statistical test. The small sample size in this pilot study was based on the pragmatics of recruitment and the necessities for examining feasibility. A future study will test this hypothesis and will include a power analysis and, therefore, an appropriate sample size.

Another limitation is that participants were established patients in the center and most of them had been in the practices more than 2 years. Both centers were located in suburban communities, which limits the findings' generalizability to urban or rural centers. Finally, this study was limited by the staffing of the individual providers during the days of data collection.

This study should be replicated to include PAs, another fast-growing provider group with similar outcome goals. A national survey of Medicare beneficiaries revealed that there was no difference in satisfaction between the provider types (physician, NP, and PA) regardless of patients' sociodemographic characteristics.18 The PAs were not included in this study because neither center employed them.

A larger multisite study is necessary to further explore patient satisfaction between provider types with patients who are newer to the practice. This study should also include an examination of the effect of specific provider attributes in light of patient satisfaction. Actual time spent waiting for the provider, actual time spent with the provider, and scheduled office visit time with the provider should be correlated with patient satisfaction. Other studies should be performed to determine why patients leave an MS practice and explore patient dissatisfaction with providers.

PRACTICE POINTS

Patient satisfaction with care provided by nurse practitioners (NPs) and physicians was high and did not differ by practitioner type.

Patient satisfaction scores for NPs and physicians increased when visits were longer than 20 minutes.

A collaborative team approach between NPs and physicians may improve access to care in MS centers.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance received to complete this study at the following MS centers: South Shore Neurologic, Patchogue, New York, and Stony Brook MS Center, Stony Brook, New York.

References

NIH National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Multiple sclerosis: hope through research. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Hope-Through-Research/Multiple-Sclerosis-Hope-Through-Research. Accessed November 3, 2016.

Prevalence of MS more than doubles estimate. National Multiple Sclerosis Society website. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/About-the-Society/MS-Prevalence. Accessed September 27, 2018.

Comprehensive care: overview. National Multiple Sclerosis Society website. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Managing-MS/Comprehensive-Care. Accessed July 19, 2019.

Halpern MT, Teixeira-Poit SM, Kane H, Frost C, Keating M, Olmsted M. Factors associated with neurologists' provision of MS patient care. Mult Scler Int . 2014; 2014: 624790.

Dall TM, Storm MV, Chakrabarti R, et al. Supply and demand analysis of the current and future US neurology workforce. Neurology . 2013; 81: 470– 478.

Halpern MT, Kane H, Teixeira-Poit S, et al. Projecting the adequacy of the multiple sclerosis neurologist workforce. Int J MS Care . 2018; 20: 35– 43.

Maloni HW. Multiple sclerosis: managing patients in primary care. Nurse Pract . 2013; 38: 24– 35.

State practice environment. American Association of Nurse Practitioners website. https://www.aanp.org/legislation-regulation/state-legislation/state-practice-environment. Accessed on September 27, 2018.

Farley H, Enguidanos E, Wiler J, et al. Patient satisfaction surveys and quality of care: an information paper. Ann Emerg Med . 2014; 64: 351– 357.

Prakash B. Patient satisfaction. J Cutan Aesthet Surg . 2010; 3: 151– 155.

Lenz ER, Mundinger MO, Hopkins SC, Lin SX, Smolowitz JL. Diabetes care processes and outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians. Diabetes Educ . 2002; 28: 590– 598.

Litaker D, Mion L, Planavsky L, Kippes C, Mehta N, Frolkis J. Physician - nurse practitioner teams in chronic disease management: the impact on costs, clinical effectiveness, and patients' perception of care. J Interprof Care . 2003; 17: 223– 237.

Carlin CS, Christianson JB, Keenan P, Finch M. Chronic illness and patient satisfaction. Health Serv Res . 2012; 47: 2250– 2272.

Lenz, ER, Mundinger, MO, Kane, RL, Hopkins, SC, Lin SX. Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: two-year follow-up. Med Care Res Rev . 2004; 61: 332– 351.

Mundinger MO, Kane RL, Lenz ER, et al. Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: a randomized trial. JAMA . 2000; 283: 59– 68.

Newhouse RP, Stanik-Hutt J, White KM, et al. Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990–2008: a systematic review. Nurs Econ . 2011; 29: 230– 251.

Budzi D, Lurie S, Singh K, Hooker R. Veterans' perceptions of care by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians: a comparison from satisfaction surveys. J Am Acad Nurse Pract . 2010; 22: 170– 176.

Hooker RS, Cipher DJ, Sekscenski E. Patient satisfaction with physician assistant, nurse practitioner, and physician care: a national survey of Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Outcomes Manage . 2005; 12: 88– 92.

Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2005; ( 2): CD001271.

Martinez-Gonzalez NA, Djalali S, Tandjung R, et al. Substitution of physicians by nurses in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res . 2014; 14: 24.

Kurtzman E, Barnow B. A comparison of nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and primary care physicians' patterns of practice and quality of care in health centers. Med Care . 2017; 55: 615– 622.

Halper J. Role of advanced practice nurse in management of multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care . 2006; 8: 33– 38.

Marshall GR, Hays RD. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18) . Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp; 1994. https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/psq.html. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

Visit-Specific Satisfaction Instrument (VSQ-9). https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/vsq9.html. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

Taylor LG. Comparing NPs, PAs and physicians. Adv Nurse Pract . 2007; 15: 53– 60.

Morgan P, Everett C, Hing E. Time spent with patients by physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants in community health centers, 2006–2010. Healthc (Amst) . 2014; 2: 232– 237.

Etier BE Jr, Orr SP, Antonetti J, Thomas SB, Theiss SM. Factors impacting Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores in orthopedic surgery spine clinic. Spine J . 2016; 16: 1285– 1289.

Gross DA, Zyzanski S, Borawski EA, Cebul RD, Stange KC. Patient satisfaction with time spent with their physician. J Fam Pract . 1998; 47: 133– 137.

Ware JE, Hays RD. Methods for measuring patient satisfaction with specific medical encounters. Med Care . 1988; 26: 393– 402.

Fan VS, Burman M, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Continuity of care and other determinants of patient satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med . 2005; 20: 226– 233.

Ogden J, Bavalia K, Bull M, et al. “I want more time with my doctor”: a quantitative study of time and the consultation. Fam Pract . 2004; 21: 479– 483.

Schwartz H, Fritz J, Govindarajan R, et al. AAN position: neurology advanced practice providers. American Academy of Neurology website. https://www.aan.com/policy-and-guidelines/policy/position-statements/neurology-advanced-practice-providers/. Accessed September 10, 2018.

Asadi-Lari M, Tamburini M, Gray D. Patients' needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: towards a comprehensive model. Health Qual Life Outcomes . 2004; 2: 32.

Keeling AW. Historical perspectives on a expanded role for nursing. Online J Issues Nurs . 2015, 20: 2.