Practice Points

- As people with multiple sclerosis (MS) age, a significant discrepancy between physical and psychosocial limitations emerges.

- Despite worsening physical outcomes, people with MS 55 years and older experience stable or improving mental health.

- Worse baseline patient-reported outcome measures are predictive of increasing disability in people with MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory, demyelinating, and neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system that results in accumulating physical and cognitive disability.1 Over the past 30 years, the effective suppression of inflammatory changes, improved symptom management, and timely rehabilitation have all contributed to extending the longevity and quality of life of people with MS.2 These improvements in MS care have led to a significant epidemiological shift, with the highest prevalence in people aged 30 to 40 years in the 1980s to those aged 55 to 64 years in the 2010s.3 These changes have prompted the need to understand the age-related effects of MS on people 55 years and older.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are increasingly accepted as an assessment tool that can capture disease impact and intervention benefits on an individual level, and understanding the perspectives of people with MS can help clinicians evaluate and improve their quality of life. PROMs can also help health care professionals comprehend the larger global impact of MS, including its effect on the economy, society, and public policy making. The National Institutes of Health has spearheaded efforts to integrate PROMs into the clinical care of various disorders by developing the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System and the Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders tools.4 Multiple foundations have initiated PROM-based initiatives (eg, Neuro-Compass, ParadigMS Foundation, and the MULTI-ACT project) to develop MS-specific tools. Recent efforts by the MS International Federation, the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Society, and the European Charcot Foundation have reinvigorated these efforts under the umbrella of the Patient Reported Outcome Initiative for MS.5,6

The LIFEware system was initially developed in the 1990s to assess PROMs data in musculoskeletal and neurological patients undergoing outpatient rehabilitation, and examines the domains of physical functioning, affective well-being, cognitive functioning, and pain experience.7 It has been previously validated, calibrated using Rasch analysis (a statistical method for PROM assessment), and has high intrarater stability (0.9-0.99).8 Using the Rasch method, the questionnaire allows cross-questionnaire analysis, and normative reference data derived from more than 300,000 outpatient evaluations provide the framework for individualized scoring. Our group has previously utilized the LIFEware system in people with MS, demonstrating its ability to predict neurological deterioration and increasing fatigue, its utility in assisting in therapy discontinuation decisions, and its relationship with MS MRI-based outcomes.9-12 The LIFEware questionnaire is also validated in other disease states, including stroke, coronary disease, and orthopedic injuries.13,14

Based on this background, we investigated PROM outcomes using the validated LIFEware questionnaire in people with MS with a baseline age of 55 years or older. We also investigated whether there is a concordance of objective disability increases with subjective PROM outcomes.

Methods

Study Population

The study population is part of the New York State MS Consortium (NYSMSC) database.9 The NYSMSC is a long-term, large-scale database founded in 1999 and contains the records of more than 10,000 people with MS. It draws data from university-based MS centers and community-based general neurology practices.

Figure 1 demonstrates the determination of the sample size and eligibility criteria for this analysis. To be included, people with MS were required to be 55 years or older, have a disease duration of at least 15 years, and have a minimum of 3 years between their baseline visit and most recent follow-up visit. The baseline visit was defined as the visit closest to when the participant turned 55 years old. The most recent follow-up visit available, at least 3 years after the baseline visit, was used for comparison. Of the 10,449 records in the database, 1909 were for people with MS who were 55 years or older and had a disease duration of more than 15 years. Of these 1909 people, 648 met the requirement of at least 2 follow-up visits with more than 3 years between them. All were diagnosed based on the current McDonald criteria at their time of enrollment.15 As part of the clinical visits, which were recorded in the NYSMSC database, all participants underwent a thorough clinical examination by a NeuroStatus-certified investigator, and their degree of disability was quantified using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS).16 In our study, the criteria utilized to indicate increasing disability are based on criteria that are widely and routinely used in all MS clinical trials. In particular, this includes an increasing EDSS score that was defined as follows: (1) EDSS increase of 1.5 or more EDSS points if baseline EDSS was 0, (2) EDSS increase of 1.0 or more points if baseline EDSS was 1.0 to 5.0 points, and (3) EDSS increase of 0.5 or more points if baseline EDSS was 5.5 or more points. Disability improvement followed the same criteria but in the opposite direction (decreasing EDSS scores over the follow-up period). Stable disability was defined as EDSS changes lower than these thresholds in either direction. Due to the small number of people with disability improvement, they were grouped with people with stable disability. An additional measure of disability was the Timed 25-Foot Walk (T25-FW) test.17 Based on the medical history and clinical examination, all participants with MS were assigned phenotypes using the 2013 Lublin criteria.18 Clinical visits due to acute disease progression (relapse) are not included in the NYSMSC database, and all visits took place during a state of stable disability. The NYSMSC project is approved by the institutional review board at the University at Buffalo, and all participants provided written consent.

PROMs

The PROMs were from the LIFEware questionnaire.10,12 It provides information over multiple domains, including the individual’s levels of physical and psychosocial limitations. It measures the physical limitations (limb functioning, bowel, bladder, fatigue, and vision) on a scale of 1, none, to 7, extremely. Cutoff scores of 5.0 or greater (moderate to severe) and less than 5.0 (none to mild) were used. A validation study found that a LIFEware cutoff of 5.0 or more had the highest optimal sensitivity and specificity for differentiating between people with MS with and without fatigue, and this cutoff was used for the other physical measures as well.19 Mobility measures (getting up, climbing stairs, standing, driving) are assessed on a scale of 1, no difficulty, to 4, unable. A cutoff of 2, some difficulty, was compared with 3 or 4, a lot of difficulty/unable. Psychosocial measures are evaluated on a scale of 1, not bothered, to 5, extremely bothered. A cutoff score of 3 separates those with no to mild issues from those with moderate to extreme issues.

For direct linear comparisons, all scores were Rasch-transformed. Mobility scores ranged from 0 to 400, physical scores from 0 to 800, and psychosocial scores from 0 to 700. In all Rasch-transformed scores, a higher value indicates less limitation.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM’s SPSS 28.0. The categorical measures were compared using the χ2 test, Student t test, and Mann-Whitney U test for normally and nonnormally distributed numerical measures. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to compare the frequency of limitations at baseline with the most recent follow-up visit. P values lower than .05 were considered statistically significant.

To assess potential multicollinearity issues, variance inflation factors were examined and found to be within acceptable ranges. A stepwise logistic regression was conducted to identify baseline PROMs associated with increasing EDSS scores. To account for the nonstandard time points acquired from the routine clinical data collection, in all statistical analyses, the duration between baseline and most recent follow-up (in years) was included as a covariate in the first block using the Enter method. The backward elimination method based on the Wald test statistic was used for PROMs, with a removal criterion of a P value greater than .10. The regression was performed with the dependent PROM as a dichotomous outcome.

Results

Study Population Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

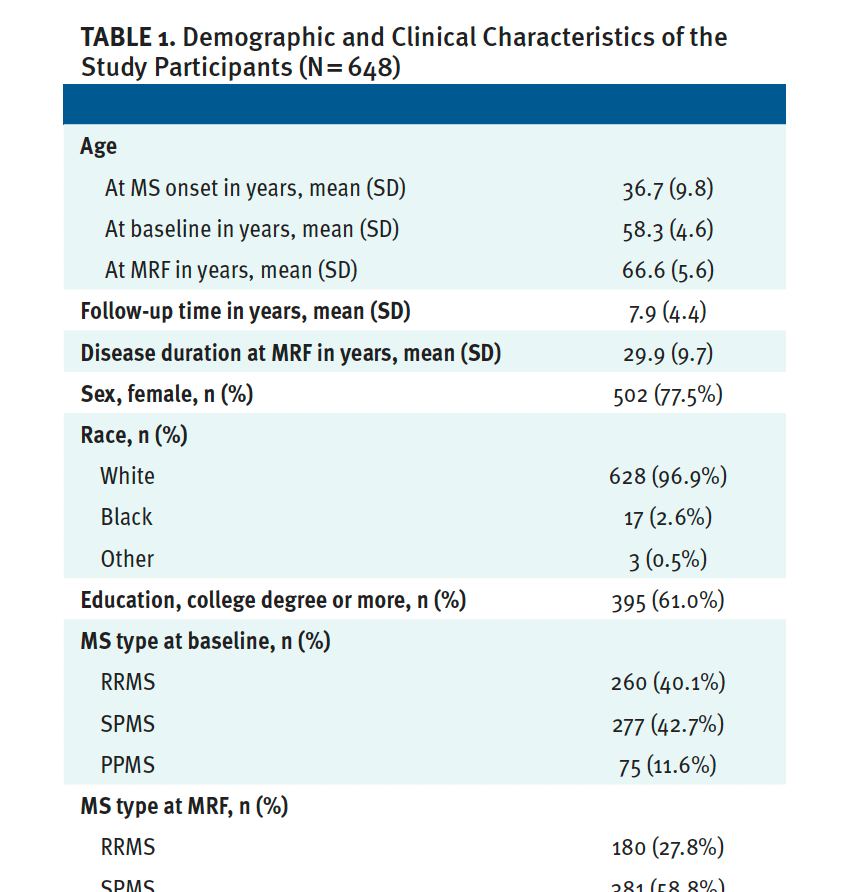

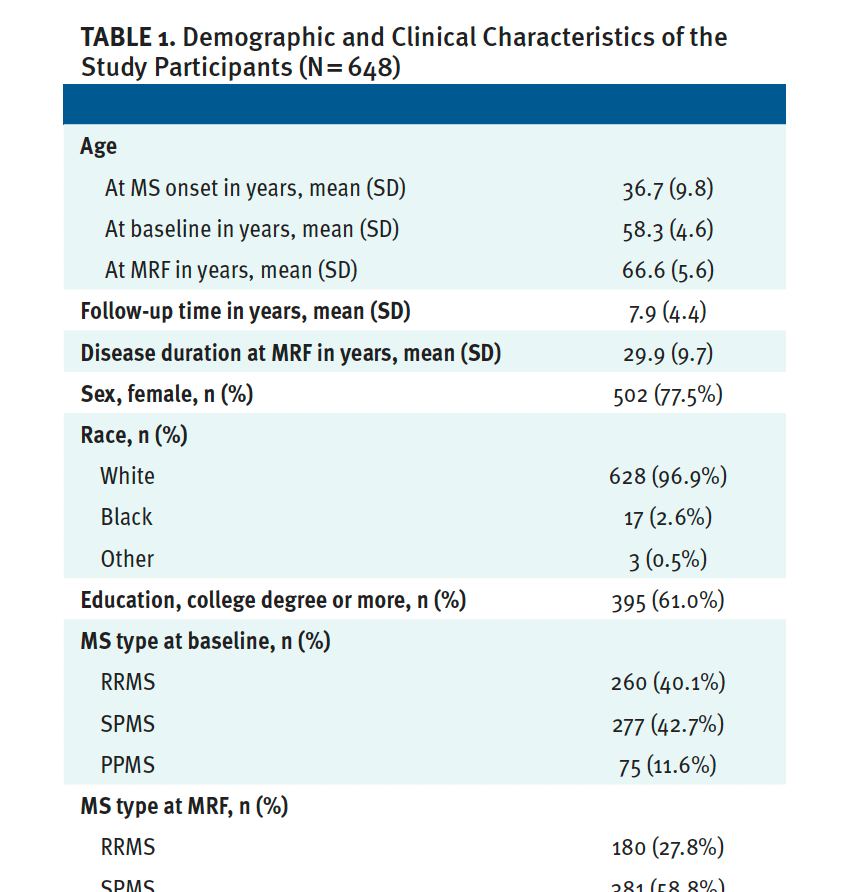

The study population is described in detail in Table 1. The average age was 58.3 (SD, 4.6) years at baseline and 66.6 (SD, 5.6) years at the most recent follow-up. Their demographic characteristics were as expected: 502 (77.5%) were women, 628 (96.9%) were White, and 395 (61.0%) had a college degree or higher level of education. The average age of MS onset was 36.7 (SD, 9.8) years. A total of 553 (85.3%) participants had used at least 1 DMT throughout their disease course.

In terms of disability, the average EDSS score was 4.8 (2.2) at baseline, which progressed to a median EDSS of 5.0 (IQR, 3.0-6.5) at the most recent follow-up. A total of 347 (56.2%) people with MS had disease progression with EDSS increases compared with 270 (43.8%) who had stable EDSS scores. Of the 270 people with stable MS, 209 (33.9%) did not have a significant change in their EDSS scores and 61 (9.9%) had disability improvement. The average T25-FW increased from a median 7.0 (range, 5.2-12.0) seconds at baseline to 8.5 (range, 5.8-15.5) seconds at the most recent follow-up.

Most participants were treated using a first-line injectable therapy; 291 (44.9%) were not treated with any DMT (47.7%). Relatively few were treated with oral DMTs (1.7%), infusion-based therapy (1.5%), or off-label medications (4.2%). No significant differences in the DMT groups occurred between their first visit (after age 55 years) and the most recent follow-up.

PROMs and Long-Term Changes in People With MS 55 Years and Over as They Age

The changes in PROMs are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. There was a significant increase in the percentage of people reporting severe/a lot of difficulties within the physical domain of the questionnaire, particularly regarding limitations in getting up from a low seat (38.4% vs 48.8%, P < .001), climbing a flight of stairs (45.5% vs 53.6%, P < .001), standing more than 30 minutes (59.3% vs 66.9%, P < .001), driving (27.9% vs 37.9%, P < .001), limitations in all extremities (P < .007), and bladder and bowel control (26.3% vs 37% and 13.1% vs 21.2%, respectively; both P < .001).

On the contrary, most of the PROM psychosocial domains significantly improved. Significantly fewer participants reported severe/a lot of limitations with regard to pessimism (23.3% vs 16.5%, P < .001), feeling tense (30.8% vs 21.0%, P < .001), feeling annoyed (23.4% vs 19.5%, P = .02), and having morbid thoughts (11.4% vs 8.1%, P = .018) at their follow-up appointment.

Longitudinal PROM stability and change between physical and psychosocial domains are shown in Figure 3 and Table S1. Physical PROMs had lower stability, with consistently stable proportions ranging from 11.2% (right lower limb limitations) to 64.3% (limitations in driving). Most mobility functions had moderate stability, including getting up from a low seat like a sofa (44.1%), climbing stairs (37.5%), and standing for more than 30 minutes (26.8%). However, psychosocial measures had high stability, including life satisfaction (87.1%), feelings of panic (89.4%), having morbid thoughts (83.9%), experiencing guilt (81.1%), and loneliness (80.1%). Psychosocial measures with substantial stability at follow-up were pessimism (68.9%), being easily annoyed (66.8%), and feeling tension (60.3%).

PROM Changes Based on Disability Progression in People With MS 55 Years and Over as They Age

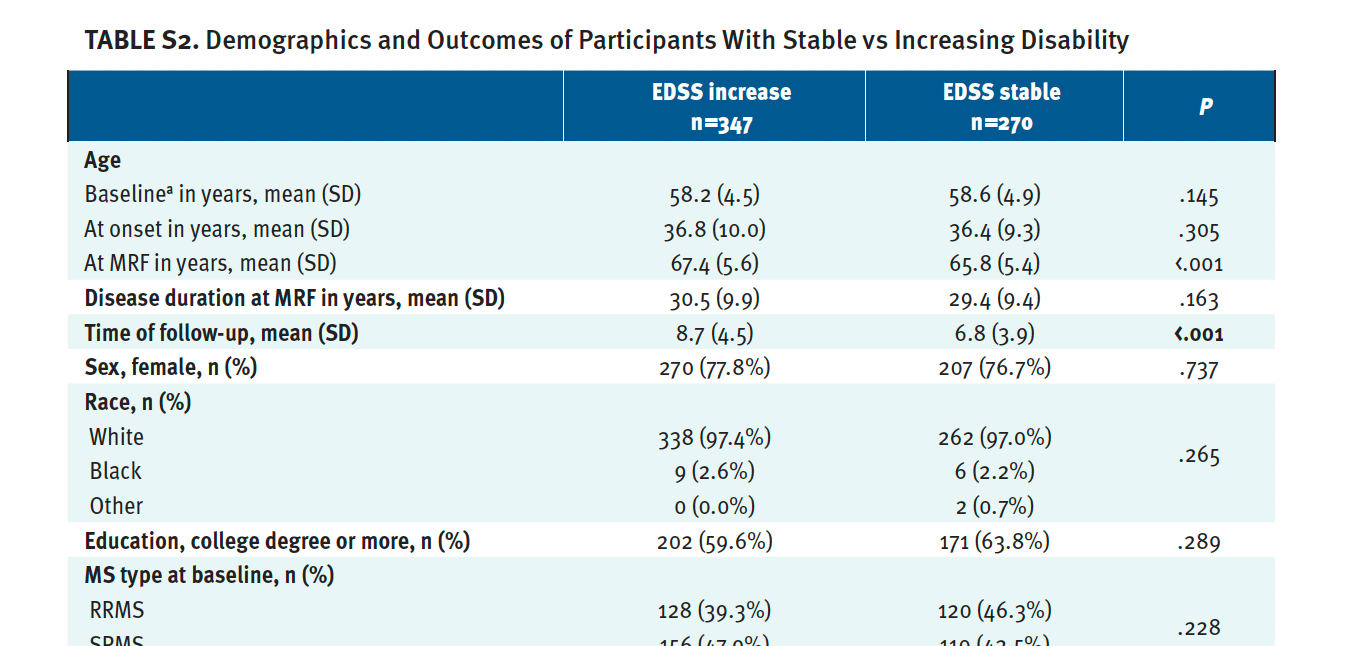

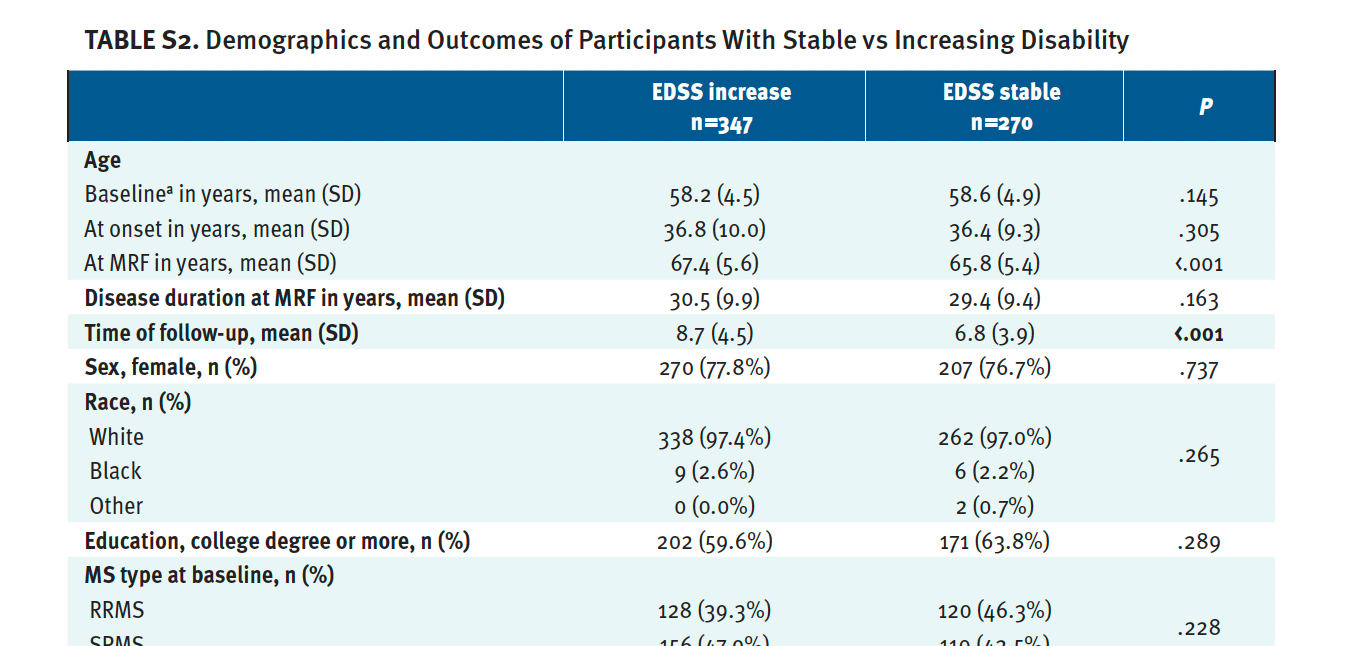

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the group that had disease progression and the group that had stable disease are shown in Table S2. As expected, the people with progression had a significantly greater change in their EDSS score at the follow-up visit (median 6.5 vs 4.5, P < .001) and a greater percentage transitioned to a progressive disease phenotype (secondary progressive MS [SPMS] at the most recent follow-up, 69.6% vs 53.7%; P < .001). People with increased EDSS scores had significantly worse mobility and physical Rasch scores at their s most recent follow-up when compared with those with stable EDSS scores (142.5 vs 211.2, P < .001 and 509.3 vs 563.7, P < .001 for mobility and physical domains). No differences were seen in the psychosocial Rasch score between groups at baseline and at the most recent follow-up.

The percentage of people with MS with increasing and stable disability who reported severe/a lot of limitations in the PROM domains is shown in Table S3. As expected, an increasing percentage with higher EDSS scores reported severe/a lot of limitations in almost all PROMs within the physical domain. In particular, those with increased EDSS scores at their most recent follow-up visit were more likely to have severe/a lot of limitations in getting up (P < .001), climbing stairs (P < .001), standing (P < .001), driving (P < .001), all 4 extremities (P < .004), bladder and bowel function (P < .007), and fatigue (P = .033). A significantly greater percentage of those with higher EDSS scores experienced moderate to severe feelings of pessimism (18.7% vs 11.8%, P = .026) and lower life satisfaction (8.8% vs 3.6%, P = .016) when compared with those with stable EDSS scores.

Importantly, despite their equivocal EDSS scores at baseline, people who had higher EDSS scores over the follow-up period reported significantly greater physical limitations at their baseline visit when compared with those with stable EDSS scores, including severe/a lot of limitations in their ability to stand for more than 30 minutes (63.8% vs 52.5%, P = .006) and severe limitations in their left lower extremity (43.1% vs 32.3%. P = .008) when compared with the people with stable EDSS scores at follow-up.

The predictive values of baseline PROMs to determine future disability progression are shown in Table 3. Severe limitations in the lower extremity (OR = 1.705, P = .016) and greater pessimism (OR = 1.926, P = .009) at baseline were both predictive of disability progression over the follow-up period. However, people reporting greater guilt (OR = 0.507, P = .022) had a lower risk of disability progression at follow-up.

Long-Term PROM Differences Between Ever vs Never DMT

The demographic, clinical, and follow-up characteristics of the people with MS who never used a DMT vs those who had utilized a DMT are shown in Table S4. Generally, a greater percentage of people who were never treated with a DMT(s) had SPMS or primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) and, in this study, their time to follow-up was significantly shorter when compared with people who were treated with a DMT(s) (5.9 vs 8.2 years, P < .001). In particular, people never treated with DMTs had worse baseline mobility and physical Rasch scores when compared with people who were treated with DMTs (184.8 vs 212.8, P = .047 for mobility and 535.3 vs 570.7, P = .023 for physical PROM scores).

The long-term categorical differentiation of PROMs between the aforementioned groups is also shown in Table S5. Overall, a significantly greater percentage of people with MS who had never used a DMT had severe/a lot of difficulties in driving (40.9% vs 25.6%, P = .003) and their right lower extremities (46.8% vs 35.9%, P = .044) when compared with people with MS who were treated with DMTs. Similar findings were seen at the most recent follow-up visit, where significantly more people not treated with DMTs were not able to drive (P = .012).

Discussion

The findings from this observational analysis are many. First, over time, the physical and psychosocial PROMs in people with MS 55 years and over demonstrate a divergent trajectory. While, in general, people with MS report an increase in their physical limitations (aspects associated with daily living and for each extremity) as they age, they also concurrently report improvement in their psychosocial well-being. Second, despite similar baseline disability scores, those who later experienced disability progression had worse physical baseline PROMs, indicating greater subjective physical limitations. Third, as expected, people with MS with significant objective disability progression over the follow-up period reported greater physical limitations, but without any corresponding decline in their psychosocial health.

The unique ability of PROMs to predict future disability progression has been previously shown, and, in some cases, these measures outperform the predictive ability of an objective neurological examination.11 For example, increases in patient-reported fatigue or physical limitations of everyday living (eg, getting up from a sofa, standing for a longer period of time) have been associated with future clinical, confirmed neurological deterioration.12,20 PROM scores from early in the disease course are also predictors of long-term MS outcomes, such as use of a unilateral support (EDSS 6.0) and transition to a progressive phenotype.11 Moreover, PROMs could bridge the gap between the radiological footprint of the disease (lesion pathology and degeneration seen on MRI) and clinical measures of physical and cognitive disability. In a recent study, LIFEware scores were well correlated with deep gray matter structures, such as the thalamus, a structure that is one of the most significant determinants of disability progression in MS.10

The closest comparisons to the changes in PROMs in our observational study are reports derived from regulatory phase 3 trials that investigated therapeutic interventions for people with SPMS or PPMS. The people with SPMS treated with natalizumab in the phase 3 ASCEND in SPMS trial (NCT01416181) had a decrease in their Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale mean psychological scores from 39.1 at baseline to 36.7 at week 96,21 which, although it was nonsignificant, was disconnected from longitudinal PROM changes with a steady decline in EDSS scores and the T25-FW.21

PROMs have also been used in interventional studies to capture the overall effect.22 In a large observational Australian study, a high-potency DMT (eg, natalizumab) had a superior effect on a significant number of PROMs.23 In a similar observational study, MS PATHS, people with MS older than 55 years also had stable quality of life measures, including stigma, fatigue, sleep, and emotional dysfunction, with findings similar to those of people with MS 54 years or younger.24 Since MS PATHS used only digital assessments and Patient-Determined Disease Steps scores, we were not able to directly compare the outcomes to our study.24

Our finding of improvement in psychosocial PROMs despite increasing physical limitations is not limited to people with MS in their 50s and 60s. Recent studies from Sweden and Switzerland provide age-based normative PROM data that also show a divergence of physical and mental outcomes.25,26 Adults aged 70 to 79 years and, particularly, adults older than 80 years, had prominent physical decline but better emotional well-being.25 Interestingly, Swedish adults aged 60 to 79 years had the best energy/fatigue outcomes when compared to any other age group.26 Similar findings have been replicated in other countries, including Australia, Norway, and Germany.27-29 We recognize that these studies are from developed Western countries and that there is a lack of global data.

The divergence of physical and mental outcomes is also seen in other disease states. The people with congenital heart disease in the APPROACH-IS trial (NCT02150603) reported an improvement in mental function and a decrease in anxiety despite their progressive sarcopenia and physical decline.30 The paradox in this study and in others may be partially attributed to a response shift where aging adults experience a change in internal values.31

The potential standardized implementation of PROMs for regulatory drug approvals requires a better understanding of their natural trajectory throughout the disease, including in people with MS as they age. Drug effectiveness has been assessed based on its impact on PROMs outcomes and PROMSs are routinely used as secondary trial outcomes in most phase 3 trials and, for example, the high-dose biotin phase 3 trial in progressive MS (NCT02936037).32 PROMs are actively used as primary trial outcomes in similar chronic neurological diseases such as myasthenia gravis,33 migraine, and Parkinson disease.34

Our study has several limitations that need to be noted. First, the study could be substantially improved by incorporating multiple social factors, such as socioeconomic status (SES), marital status, personality traits, and the extent of participants’ social networks.35-37 We plan to explore the effects of SES and social determinants of health on PROM progression in a future project with NYSMSC, as we are in the process of updating the consortium database to include local zip code-based and census income data, distance to health care facilities, and participant education levels. All these factors may have both independent and mediating effects, with different PROMs potentially demonstrating serendipitous association (eg, guilt and disability progression). Second, the time of follow-up between those with increasing EDSS scores and those with stable EDSS scores differed by approximately 2 years, a fact that could have skewed the findings. Longer follow-up times allow a greater likelihood of disability progression, and future analysis should match groups based on baseline characteristics. Lastly, a potential age-matched health control group could be crucial to differentiate disease effects from expected PROM changes due to increasing age.

Conclusions

Physical and psychosocial PROMs diverge in people with MS 55 years and older as they age, with increased physical limitations but improved mental health over time. Experiences accumulated throughout long-term experience with a chronic disease may be crucial in maintaining a positive outlook despite physical challenges. Studying people with MS as they age could potentially improve mental health interventions for all people with MS.