Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Gastrointestinal Tolerability of Delayed-Release Dimethyl Fumarate in a Multicenter, Open-Label Study of Patients with Relapsing Forms of Multiple Sclerosis (MANAGE)

Author(s):

Background: In phase 3 trials, delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF; also known as gastroresistant DMF) demonstrated efficacy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). Gastrointestinal (GI) events were associated with DMF treatment. The single-arm, open-label MANAGE study examined the incidence, severity, duration, and management of GI events in adults with relapsing MS initiating DMF treatment in clinical practice in the United States shortly after marketing approval.

Patients and Methods: Patients (N = 233) took DMF for up to 12 weeks and recorded information regarding GI events using an eDiary and numerical rating scales.

Results: Overall, 54.1% of patients used symptomatic therapy and had GI symptoms. The incidence of GI events was highest in the first month of treatment. The duration of GI events varied by event type, and severity was generally mild to moderate. Decreased severity was seen in patients treated with antacids, bismuth subsalicylate, acid-secretion blockers, antidiarrheals, and antiemetics. Less than 10% of patients were using symptomatic therapy for GI events by week 12 of DMF treatment. A modest reduction in severe GI events was observed in patients who regularly took DMF with food compared with patients who did not. The incidence of GI-related events was comparable in patients with or without a history of GI abnormalities and in patients who did or did not use alcohol or tobacco.

Conclusions: Gastrointestinal events associated with DMF are generally transient, mild to moderate in severity, and manageable. Symptomatic therapy and dosing with food may mitigate these events.

Delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF; also known as gastroresistant DMF) demonstrated significant efficacy and an acceptable safety profile in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 DEFINE (Determination of the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Fumarate in Relapsing-Remitting MS)1 and CONFIRM (Comparator and an Oral Fumarate in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis)2 studies. Common adverse events associated with DMF treatment included gastrointestinal (GI) events. These events occurred most frequently in the first month, declining thereafter; most were rated as mild or moderate in severity (91%−96%) and resolved during the study (93%−96%).3 Although discontinuation of DMF treatment due to GI events was relatively low in clinical trials,3 the potential impact of these events on adherence is a concern in clinical practice.

In recent surveys of clinicians with experience managing GI events in DMF-treated patients, the following management strategies were commonly recommended: 1) counseling and setting expectations about the nature of the events, 2) dosing with food (especially fatty foods) as a prophylactic measure, and 3) using symptomatic therapy to manage symptoms as needed.4 5 Although basic information about the nature of the events is available from DEFINE and CONFIRM, a better understanding requires a study designed specifically for the purpose of characterizing the events in a real-world setting. Furthermore, although patients participating in DEFINE and CONFIRM were instructed to take DMF with food and were permitted to use symptomatic therapy, the efficacy of these measures was not assessed.

MANAGE (a Multicenter, Open-Label, Single-Arm Study of GastroiNtestinal Tolerability in Patients with RelApsinG Forms of MultiplE Sclerosis Receiving Dimethyl Fumarate) was launched in the United States shortly after DMF received marketing approval from the US Food and Drug Administration. The study incorporated a method for examining characteristics of GI events at a more detailed level than in the pivotal studies: prospective, prompted self-report using an eDiary device and numerical rating scales developed specifically for this purpose.

The objectives of MANAGE were to examine the incidence, severity, and duration of GI-related events in DMF-treated patients and to describe the impact of symptomatic therapy. MANAGE also examined the effect of dosing with food and potential risk factors for GI-related events, including a history of GI abnormalities and the use of alcohol or tobacco.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Key eligibility criteria included age 18 years or older, no history of treatment with DMF or fumaric acid esters, a confirmed diagnosis of relapsing MS, and a pre-enrollment decision to treat with DMF. Key exclusion criteria included a history of significant GI disease or long-term use (≥7 consecutive days) of GI symptomatic therapy within 1 month before enrollment.

Design

MANAGE is a multicenter, open-label, single-arm study. Patients took DMF for 12 weeks and recorded pertinent information regarding GI-related events daily using an eDiary device, as described later herein. The DMF was dosed orally at 120 mg twice daily for 7 days and at 240 mg twice daily thereafter. Patients were instructed to take the study medication with a meal or within 1 hour after a meal. The use of concomitant medications was left to the discretion of the investigator.

Patients returned to the study site at weeks 4, 8, and 12 for safety assessments, including monitoring of adverse events (defined as any untoward medical occurrence that did not necessarily have a causal relationship with study treatment) leading to discontinuation of study treatment, serious adverse events, concomitant medications, and alcohol or tobacco use. A safety follow-up was performed by telephone 4 weeks after administration of the last dose of study treatment.

Assessments

The GI events were self-reported by participants using an eDiary with two questionnaires designed to obtain detailed information about the incidence, severity, duration, and onset of GI symptoms. The questionnaires were based on and adapted from validated flushing questionnaires used in studies of niacin.6 The Modified Overall Gastrointestinal Symptom Scale (MOGISS) assessed global GI events (defined as one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, lower abdominal pain, vomiting, indigestion, constipation, bloating, and flatulence) and their effect on the patient during the 24 hours before each morning dose. The Modified Acute Gastrointestinal Symptom Scale (MAGISS) assessed individual acute GI-related symptoms (nausea, diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, lower abdominal pain, vomiting, indigestion, constipation, bloating, and flatulence) that the patient experienced during the 10 hours after each morning and evening dose. In both questionnaires, items were rated on a 10-point numerical rating scale, where 0 = no events, 1 to 3 = mild events, 4 to 6 = moderate events, 7 to 9 = severe events, and 10 = extreme events (Supplementary Figure 1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org). For the MAGISS, patients were asked to indicate the start and end times of each individual GI-related event that they experienced.

Adverse events that led to treatment discontinuation or study withdrawal or that were classified as serious were recorded on case report forms during safety visits in addition to being captured in the eDiary. The GI events not meeting these criteria were captured in the eDiary but were not recorded on case report forms.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were based on the safety population, defined as all patients who received at least one dose of study treatment. Because GI events were reported frequently by placebo-treated individuals in a previous study,7 many of the analyses focused on patients who not only experienced GI events but also used symptomatic therapy for those events. The data are summarized using descriptive statistics.

Analyses of the frequency, severity, and duration of overall GI events were based on the MOGISS and the MAGISS. A participant was counted as having an overall GI event if he or she had a score of at least 1 for at least one of the acute GI-related events. Analyses of the frequency, severity, and duration of acute GI-related events were based on the MAGISS. For patients with more than one acute GI-related event during a visit interval, the average duration for the visit interval was used, and the event with the highest severity score was used in calculations of mean worst severity scores (WSS).

Ad hoc analyses examined the effect of initiating symptomatic therapy by showing the daily MOGISS score for overall GI events or the mean intensity rating for GI symptoms of particular interest (nausea, diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, lower abdominal pain, and vomiting) before and after initiation of symptomatic therapy.

Ethical Conduct of the Study

The study was conducted at multiple sites in the United States in accordance with Title 21, US Code of Federal Regulations; the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines on Good Clinical Practice8; the European Union Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC; and the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.9 The investigators obtained approval for the study protocol from the following ethics committees: Copernicus Group Independent Review Board, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina; Providence Health and Services institutional review board, Portland, Oregon; Western Institutional Review Board, Olympia, Washington; Shepherd Center Research Review Committee, Atlanta, Georgia; Georgetown University institutional review board, Washington, DC; Wheaton Franciscan Healthcare institutional review board, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and the Institutional Review Board and Research Human Subjects Committee, Boston, Massachusetts. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before performing any study-related activities.

Results

Patients

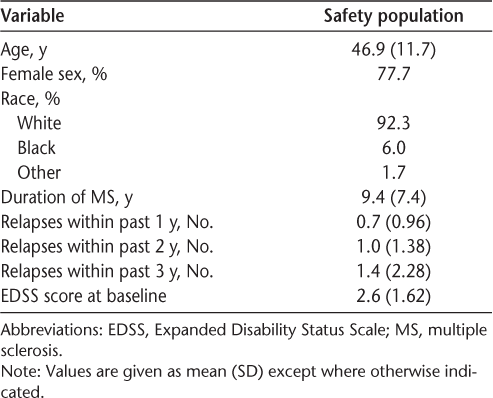

The safety population comprised 233 patients; baseline demographic and disease characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 202 patients (86.7%) completed the study. Patient compliance with the eDiary was high (89%).

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of the 233 study participants

Adverse Events

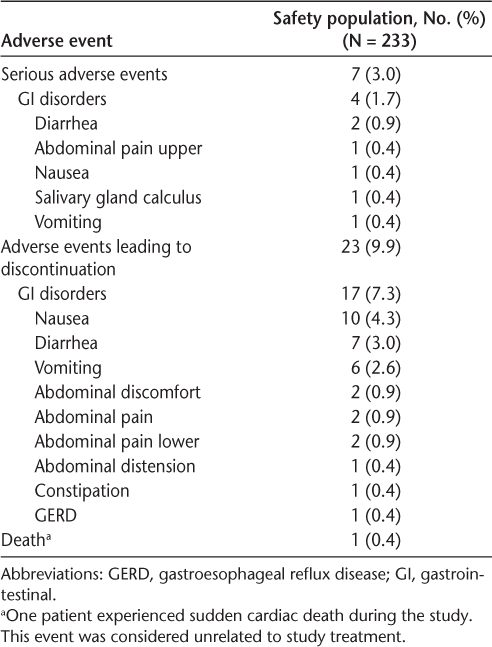

Key safety and tolerability data are summarized in Table 2. Seven patients (3.0%) experienced at least one serious adverse event. Among them, four patients (1.7%) experienced at least one GI-related serious adverse event, including diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, lower abdominal pain, nausea, salivary gland calculus, and vomiting. Non–GI-related serious adverse events included lymphadenitis, atrial fibrillation, sudden cardiac death, increased troponin levels, pain in the jaw, and confusional state. Of the non–GI-related serious adverse events, only lymphadenitis was considered to be related to study treatment.

Summary of key safety and tolerability data

Sudden cardiac death was experienced by a 52-year-old man. At the time of the event, he had received study treatment for 71 days. The patient's medical history included obesity and probable metabolic syndrome. This event was considered unrelated to study treatment. No other on-study deaths were reported.

Twenty-three patients (9.9%) discontinued study treatment due to adverse events, including 17 (7.3%) who discontinued due to GI-related adverse events (Table 2). The most common GI-related events leading to discontinuation were nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting. Patients may have discontinued study treatment due to more than one of these events.

eDiary-Reported GI Events

Because the results for overall GI events as assessed by the MOGISS and the MAGISS were similar, we focus on the MOGISS for overall GI events and on the MAGISS for acute GI events.

Frequency of GI Events and Symptomatic Therapy Use

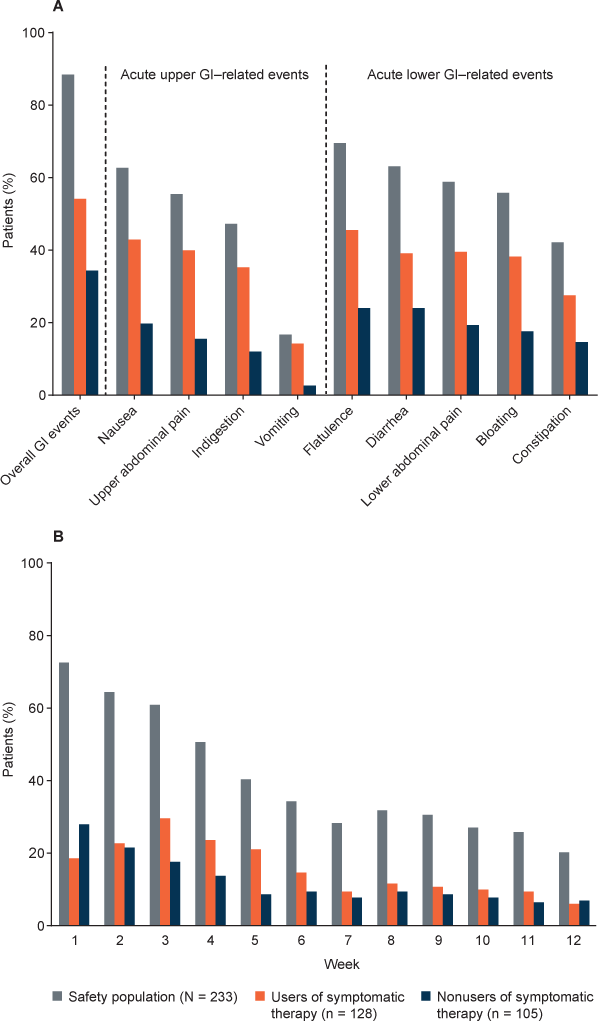

In the safety population, across the 12-week study, 88.4% of patients reported a GI event. The incidence of acute upper GI-related events ranged from 16.7% (vomiting) to 62.7% (nausea), and the incidence of acute lower GI events ranged from 42.1% (constipation) to 69.5% (flatulence) (Figure 1A). The prevalence of overall GI events was highest in the first month of treatment, declining thereafter, from 85.8% in weeks 1 to 4 to 55.4% in weeks 5 to 8 and 40.3% in weeks 9 to 12 (Figure 1B).

A, Frequency of overall gastrointestinal (GI) events (assessed by the Modified Overall Gastrointestinal Symptom Scale [MOGISS]) and acute upper and lower GI events (assessed by the Modified Acute Gastrointestinal Symptom Scale) in the safety population, users of GI symptomatic therapy, and nonusers of GI symptomatic therapy across the 12-week study. B, Frequency of overall GI events (assessed by the MOGISS) in the safety population, users of GI symptomatic therapy, and nonusers of GI symptomatic therapy by study week. The denominator for the percentages is the safety population.

Patients who reported overall GI events and used symptomatic therapy composed 54.1% of the safety population. Patients who reported overall GI events and did not use symptomatic therapy composed 34.3% of the safety population. The frequency of overall and acute GI events was higher in users compared with nonusers of symptomatic therapy (Figure 1A). The prevalence of overall GI events requiring symptomatic therapy declined during the study, from 45.5% in weeks 1 to 4 to 27.9% in weeks 5 to 8 and 18.0% in weeks 9 to 12; by week 12, less than 10% of patients were using symptomatic therapy (Figure 1B).

The incidence of symptomatic therapy use was highest in the first month of treatment and declined thereafter, from 45.5% in weeks 1 to 4 to 29.6% in weeks 5 to 8 and 20.6% in weeks 9 to 12. By week 12, less than 10% of patients were using symptomatic therapy. The most-used classes of symptomatic therapy were antacids (eg, calcium carbonate, 24.5%), bismuth subsalicylate (21.0%), acid-secretion blockers (including proton pump inhibitors and histamine type 2 receptor blockers; eg, omeprazole, 18.5%), antibloating/anticonstipation agents (eg, simethicone, 14.2%), antidiarrheals (antiperistaltic agents; eg, loperamide, 13.7%), and centrally acting antiemetics (eg, ondansentron, 7.7%).

Duration of GI Events

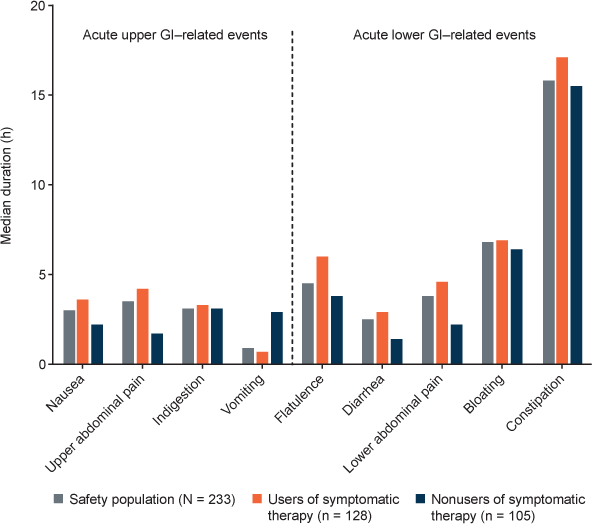

In the safety population, the median duration of acute GI-related events varied across event types, from a low of 0.9 hours (vomiting) to a high of 15.8 hours (constipation) (Figure 2). The median duration of acute GI events was generally similar in users compared with nonusers of symptomatic therapy.

Median duration of acute upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) events (assessed by the Modified Acute Gastrointestinal Symptom Scale) in the safety population, users of GI symptomatic therapy, and nonusers of GI symptomatic therapy. For patients with more than one GI-related event during a visit interval, the average duration for the visit interval was used.

Severity of GI Events

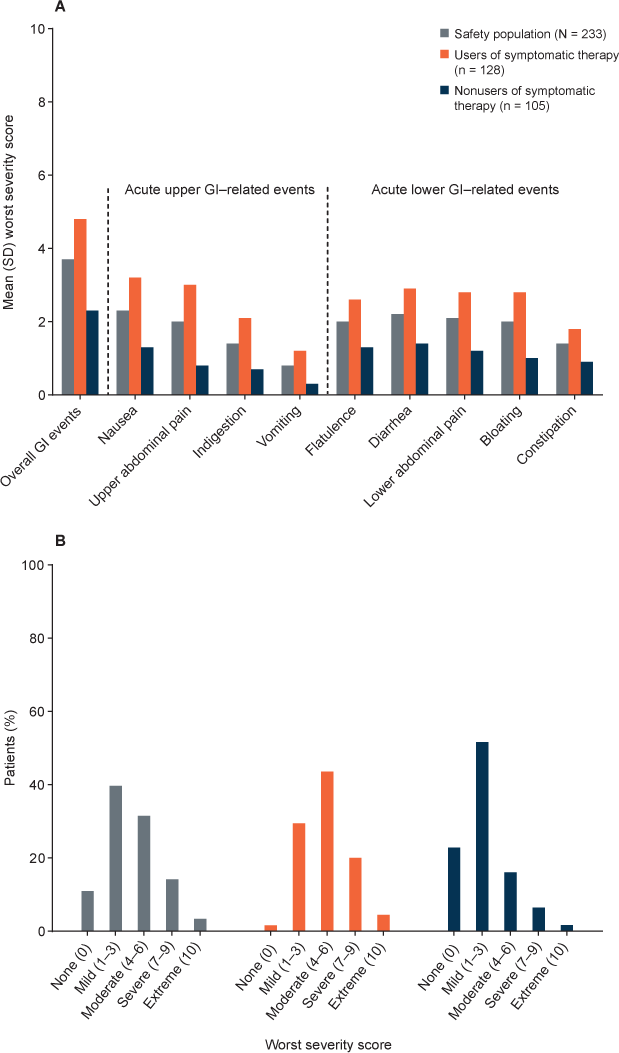

In the safety population, the mean WSS for overall GI events (3.7) fell into the mild (1−3) to moderate (4−6) range, and the mean WSSs for all acute upper and lower GI-related events fell into the mild range (Figure 3A). Mean WSSs for overall GI events and acute GI-related events were somewhat higher in users compared with nonusers of symptomatic therapy, with some means falling into the moderate range. However, there was considerable variability.

A, Mean (SD) worst severity scores for overall gastrointestinal (GI) events (assessed by the Modified Overall Gastrointestinal Symptom Scale [MOGISS]) and acute upper and lower GI events (assessed by the Modified Acute Gastrointestinal Symptom Scale) in the safety population, users of GI symptomatic therapy, and nonusers of GI symptomatic therapy. B, Distribution of worst severity scores for overall GI events (assessed by the MOGISS) in the safety population, users of GI symptomatic therapy, and nonusers of GI symptomatic therapy. Severity was rated on a 10-point numerical rating scale, where 0 = no events, 1 to 3 = mild events, 4 to 6 = moderate events, 7 to 9 = severe events, and 10 = extreme events.

For most patients in the safety population, the WSS was mild (39.7%) or moderate (31.5%) (Figure 3B). In users compared with nonusers of symptomatic therapy, the distribution of WSSs for overall GI events was shifted somewhat to the right, reflecting higher scores. The percentages of patients with WSSs characterized as mild, moderate, severe, and extreme were 29.7%, 43.8%, 20.3%, and 4.7%, respectively, for users of symptomatic therapy, and 51.9%, 16.3%, 6.7%, and 1.9%, respectively, for nonusers of symptomatic therapy.

In patients who discontinued study treatment due to GI events, the mean (SD) WSS for overall GI events was 6.9 (2.45), falling into the moderate (4−6) to severe (7−9) range. The percentages of patients who discontinued study treatment with WSSs characterized as mild, moderate, severe, and extreme were 0.4%, 1.7%, 4.3%, and 0.9%, respectively.

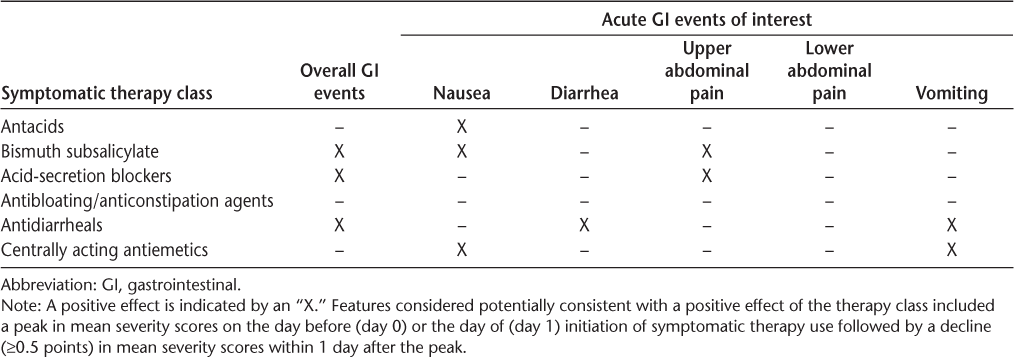

Effect of Symptomatic Therapy

Using severity scores for overall GI events (assessed by the MOGISS) and acute GI events of particular interest (nausea, diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, lower abdominal pain, and vomiting; assessed by the MAGISS), a post hoc, descriptive analysis was conducted to assess preliminarily the effect of the most-used classes of symptomatic therapy on the severity of GI events. Daily mean severity scores were plotted for patients taking antacids, bismuth subsalicylate, acid-secretion blockers, antibloating/anticonstipation agents, antidiarrheals, or centrally acting antiemetics, beginning 4 days before (day −3) the first day the symptomatic therapy was used (day 1) and continuing to the end of the study. For this exploratory analysis, a peak in mean severity scores on the day before (day 0) or the day of initiation of symptomatic therapy use (day 1) and a decline (≥0.5 points) in mean severity scores within 1 day after peak were considered potentially consistent with a positive effect of the therapy class. The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 3.

Symptomatic therapy classes potentially showing a positive effect on the severity of overall GI events or acute GI events of interest based on a post hoc descriptive analysis of daily symptom severity scores

Overall GI Events. For the most-used classes of symptomatic therapies, mean severity scores for overall GI events peaked on the day before or the day of symptomatic therapy initiation and declined thereafter (Supplementary Figure 2). Peak scores ranged from 2.2 (antibloating/anticonstipation agents) to 3.4 (antidiarrheals). The rate of decline varied by symptomatic therapy class. Immediate (within 1 day after peak) and pronounced (≥0.5-point) drops were seen with bismuth subsalicylate, acid-secretion blockers, and antidiarrheals.

Nausea. Mean severity scores for nausea peaked on the day before or the day of symptomatic therapy initiation and dropped by at least 0.5 points within 1 day after peak in patients taking antacids, bismuth subsalicylate, or centrally acting antiemetics (Supplementary Figure 3). The most pronounced drop was with centrally acting antiemetics, with mean scores falling from a peak of 3.5 (day 0) to 1.1 (day 1). With antacids, mean scores fell from a peak of 1.1 (day 1) to 0.5 (day 2), and for bismuth subsalicylate, mean scores fell from a peak of 2.1 (day 0) to 0.9 (day 1).

Diarrhea. Antidiarrheals were the only symptomatic therapy class in which a peak in mean severity scores for diarrhea was observed on the day before the day of symptomatic therapy initiation followed by a drop of at least 0.5 points within 1 day after peak (Supplementary Figure 4). The peak severity score was 3.4 on day 0, falling to 1.1 on day 1.

Upper Abdominal Pain. Mean severity scores for upper abdominal pain peaked on the day before the day of symptomatic therapy initiation and dropped by at least 0.5 points within 1 day after peak in patients taking bismuth subsalicylate or acid-secretion blockers (Supplementary Figure 5). With acid-secretion blockers, mean scores fell from a peak of 2.0 (day 0) to 1.1 (day 1), and for bismuth subsalicylate, mean scores fell from a peak of 1.9 (day 0) to 1.3 (day 1).

Lower Abdominal Pain. No symptomatic therapy class had a peak in mean severity scores for lower abdominal pain on the day before or the day of symptomatic therapy initiation followed by a decline of at least 0.5 points within 1 day after peak (Supplementary Figure 6). However, bismuth subsalicylate just missed this criterion, with mean scores falling from a peak of 1.48 (day 0) to 1.0 (day 1).

Vomiting. Mean severity scores for vomiting peaked on the day before or the day of symptomatic therapy initiation and dropped by at least 0.5 points within 1 day after peak in patients taking antidiarrheals or centrally acting antiemetics (Supplementary Figure 7). The most pronounced drop was with centrally acting antiemetics, with mean scores falling from a peak of 1.6 (day 0) to 0.3 (day 1). With antidiarrheals, mean scores fell from a peak of 1.1 (day 1) to 0.5 (day 2).

Dosing with Food

Despite the instruction to take DMF with or within 1 hour after a meal, only 39 patients (17%) always did so. There was no association between dosing with food and the occurrence of overall GI events: 19.2% of patients without GI events and 16.5% of patients with GI events reported regularly taking DMF with food. The distributions of WSSs for overall GI events were generally comparable between patients who always took DMF with food versus those who did not (Supplementary Figure 8). However, the percentage of patients with a WSS characterized as mild was higher in patients who always took DMF with food compared with patients who did not (46.2% vs. 38.3%), and the percentage of patients with a WSS characterized as severe was lower in patients who always took DMF with food compared with patients who did not (7.7% vs. 15.5%).

History of GI Abnormalities

Forty patients (17.2%) had a history of GI abnormalities (type not classified). There was no association between GI history and the occurrence of overall GI events: 18.5% of patients without GI events and 17.0% of patients with GI events reported a history of GI abnormalities. There was no difference in the mean (SD) WSS for overall GI events in patients with a GI history (3.7 [2.42]) compared with patients with no GI history (3.7 [2.69]).

Alcohol or Tobacco Use

In the 141 patients (61%) reporting alcohol use (beer, 24%; wine, 36%; liquor/spirits, 24%), there was no association between alcohol use and the occurrence of overall GI events: alcohol use was reported by 55.6% of patients without GI events and 61.2% of patients with GI events. There was no difference in the mean (SD) WSS for overall GI events in patients who used alcohol (3.9 [2.62]) compared with patients who did not (3.3 [2.64]).

In the 85 patients (37%) who reported using tobacco (cigarettes, 36%; cigars, <1%; smokeless tobacco, <1%), there was no association between tobacco use and the occurrence of overall GI events: tobacco use was reported by 40.7% of patients without GI events and 35.9% of patients with GI events. There was no difference in the mean (SD) WSS for overall GI events in patients who used tobacco (4.1 [2.89]) compared with patients who did not (3.5 [2.46]).

Discussion

In the DEFINE1 and CONFIRM2 trials, GI-related adverse events were recorded along with other adverse events by investigators at monthly clinic visits based on retrospective reports by patients. MANAGE was designed specifically to characterize GI-related events and incorporated a reporting method in which patients were prompted to self-report relevant information about GI symptoms daily using an eDiary device and two numerical rating scales: the MOGISS and the MAGISS. Compared with more traditional reporting methods, prospective, prompted self-report potentially increases the accuracy of event reporting8 10 and allows for the analysis of event characteristics at a more detailed level.

Comparisons between studies with significant methodological differences should be made with caution; however, the notable difference in the frequency of GI events as reported in the present study (88.4% overall) compared with DEFINE and CONFIRM (integrated analysis: 40% in the DMF 240 mg twice daily group and 31% in the placebo group3) deserves comment. It has been found that reporting of adverse events is increased when patients are prompted (eg, with a checklist of symptoms) versus when they are not9 11 and when patients use a diary for reporting compared with other methods.12 Hence, the use of proactive, twice daily self-report of GI events using targeted questionnaires and an eDiary may be an explanation for the relatively high incidence of GI events in MANAGE. Consistent with this, in another study using the same eDiary method for reporting of GI events, the incidence of overall GI events was similarly high: 81% in individuals (healthy volunteers) receiving DMF with placebo pretreatment and 66% in those receiving placebo with placebo pretreatment (study weeks 1–4).7 The incidence in placebo-treated, DMF-naïve healthy volunteers in that study may speak to the “normal” or “background” rate of overall GI events, independent of potential drug adverse effects.

Notably, serious adverse events and adverse events leading to discontinuation of study treatment were infrequent, despite the relatively high incidence of eDiary-reported GI-related events. This finding suggests that GI-related events associated with DMF treatment, although common (particularly in the early treatment period), are generally mild and not bothersome enough to lead to treatment interruption.

Findings regarding the severity of GI-related events were consistent with previous findings. In DEFINE and CONFIRM, events were generally rated as mild to moderate in severity.3 In MANAGE, the mean WSS for overall GI events fell into the mild-to-moderate range, and the mean WSSs for all acute upper and lower GI-related events fell into the mild range. There were some differences among event types; for example, the mean WSS was lowest for vomiting and highest for nausea, but scores were quite variable overall. Not surprisingly, the mean WSS for overall GI events was higher in those who discontinued study treatment due to GI-related events compared with the overall safety population.

DEFINE and CONFIRM were not designed to examine adverse event duration as an endpoint, allowing only an estimate based on the recorded start and stop dates of resolved events. A preliminary post hoc analysis of data from DEFINE and CONFIRM showed that the median duration of resolved GI tolerability events was less than 2 weeks.3 In MANAGE, patients were prompted to report onset and offset times for individual GI-related events as they occurred, providing a more direct measure of duration. The results show that although there is considerable variability in the duration of different event types, all events occurred on a scale of hours rather than days or weeks. Most but not all patients who reported overall GI events used symptomatic therapy. The incidence of overall GI events and acute GI-related events was higher in users of symptomatic therapy compared with nonusers; but in both subgroups, the incidence peaked in weeks 1 to 4 and declined thereafter. Symptomatic therapy use over time paralleled the incidence of overall GI events, peaking in weeks 1 to 4 and declining thereafter; importantly, less than 10% of patients were using symptomatic therapy for GI events by week 12. The median duration of acute GI-related events was generally similar in users and nonusers of symptomatic therapy, whereas mean WSSs for overall GI events and acute GI-related events were higher in users of symptomatic therapy compared with nonusers.

MANAGE was not designed to rigorously assess the effect of symptomatic therapy on GI events associated with DMF. However, a post hoc descriptive analysis was conducted to examine preliminarily the effect of the most commonly used symptomatic therapy classes using daily mean severity scores for overall GI events and acute GI events of interest. A peak in mean severity scores on the day before or the day of initiation of symptomatic therapy use followed by an immediate (within 1 day after peak) and significant (≥0.5-point) decline in mean severity scores was considered potentially consistent with a positive effect of the therapy class.

Based on this analysis, bismuth subsalicylate, acid-secretion blockers, and antidiarrheals seemed to reduce the severity of overall GI events, whereas antacids, antibloating/anticonstipation agents, and centrally acting antiemetics did not have an appreciable effect. Regarding acute GI symptoms, potential mitigating effects were observed with antacids, acid-secretion blockers, and antidiarrheals for nausea; antidiarrheals for diarrhea; bismuth subsalicylate and acid-secretion blockers for upper abdominal pain; and antidiarrheals and centrally acting antiemetics for vomiting. None of the most-used symptomatic therapy classes met the criteria for a mitigating effect on lower abdominal pain, although bismuth subsalicylate just missed meeting the criteria. Antibloating/anticonstipation agents did not show a positive effect on any acute GI symptom. Altogether, these findings are largely in keeping with the results of surveys of clinicians with experience managing GI events associated with DMF, in which antacids, bismuth, acid-secretion blockers, antidiarrheals, and antiemetics were among the most commonly recommended management strategies for GI symptoms, including nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and vomiting.4 5

The analysis of the effect of symptomatic therapy classes on the severity of GI events has several limitations. As with any post hoc, descriptive analysis, the results should be considered exploratory and should be interpreted with an appropriate degree of caution. MANAGE was not designed to assess the efficacy of symptomatic therapies; hence, there was no randomization of patients to treatment with specific therapies and no placebo control group. At the discretion of the investigator, patients were free to use symptomatic therapies of their choosing and could have used more than one therapy or therapy class simultaneously. The number of patients using any particular therapy class was relatively small and declined during the study. Patients taking symptomatic therapy were not asked to specify which symptoms they were attempting to treat; hence, patients taking a particular symptomatic therapy class were included in the analysis of every individual GI symptom for that class, although they may have taken the therapy for only one or a subset of those symptoms. Finally, there was a gradual decline in severity scores across the duration of the study. This decline is unlikely to be related to symptomatic therapy and may reflect a natural decline in severity with continuing DMF use, similar to the decline in the incidence of GI events with continuing DMF use as reported previously.1–3

In addition to these symptomatic therapies, albeit in very small numbers, notable improvements in GI symptoms were also seen with the antiallergy medication montelukast (Singulair; Merck & Co Inc, Kenilworth, NJ) in two patients with events to be evaluated, consistent with the results of a recent study.13 In both of these patients, the effect was immediate, with GI symptom severity declining to and largely remaining at zero.

Dosing with food was recommended by an expert panel of investigators as a prophylactic measure for GI events associated with DMF.4 5 In MANAGE, patients were instructed to take DMF with or within 1 hour after a meal, but not all patients regularly did so. A descriptive analysis of WSSs revealed a modest reduction in severe GI-related events in patients who regularly took DMF with a meal compared with patients who took DMF without a meal.

Thus far, no risk factors have been identified for GI-related events associated with DMF. We found no difference in the incidence or severity of overall GI events in patients with or without a history of GI abnormalities. However, because the types of GI abnormalities were not classified, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Alcohol or tobacco use did not seem to influence the experience of GI events.

MANAGE was an observational study conducted to provide real-world experience of the GI tolerability of DMF, but, as such, it has several limitations. There was no placebo control group, and patients were not randomized to groups that did or did not regularly take study medication with a meal or use alcohol or tobacco. The efficacy of symptomatic therapies and dosing with food was assessed retrospectively in a descriptive analysis. Patient selection may have been biased by prescribers by excluding patients with a GI history from DMF treatment. Finally, GI symptoms (particularly constipation) are prevalent in people with MS,14 and this was not controlled for. Prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled studies are needed to more rigorously investigate the efficacy of specific putative mitigation strategies.

Conclusion

The results of MANAGE are broadly consistent with those of the pivotal phase 3 trials and indicate that GI-related events associated with DMF are generally transient, mild to moderate in severity, and manageable. Dosing with food and the use of symptomatic therapy may help mitigate these events.

PracticePoints

Gastrointestinal (GI) events associated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF; also known as gastroresistant DMF) are generally transient, mild to moderate in severity, and of variable duration. Regularly taking DMF with food and the use of symptomatic therapy may help mitigate GI-related events associated with DMF.

In general, a decrease in the mean severity scores for overall GI events was seen in patients who received treatment with one or more medications in the following categories: antacids, bismuth subsalicylate, acid-secretion blockers, antibloating/anticonstipation agents, antidiarrheals, and antiemetics. Less than 10% of patients were using symptomatic therapy for GI events by week 12 of DMF treatment.

The incidence of GI-related events was comparable in patients with or without a history of GI abnormalities, patients who did or did not use alcohol, and patients who did or did not use tobacco.

Acknowledgments

Karyn M. Myers, PhD (Biogen), wrote the first draft of the manuscript based on input from authors.

References

Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 1098–1107.

Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2012;1367:1673]. N Engl J Med.. 2012; 367: 1087–1097.

Phillips JT, Selmaj K, Gold R, et al. Clinical significance of gastrointestinal and flushing events in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate. Int J MS Care. 2015; 17: 236–243.

Phillips JT, Erwin A, Agrella S, Kremenchutzky M, Kramer J, Fox R. A Delphi panel to address management of gastrointestinal side effects observed with use of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and the 8th Cooperative Meeting with the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS); May 28–31. 2014; Dallas, TX.

Phillips JT, Hutchinson M, Fox R, Gold R, Havrdova E. Managing flushing and gastrointestinal events associated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate: experiences of an international panel. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014; 3: 513–519.

Norquist JM, Watson DJ, Yu Q, Paolini JF, McQuarrie K, Santanello NC. Validation of a questionnaire to assess niacin-induced cutaneous flushing. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007; 23: 1549–1560.

O'Gorman J, Russell HK, Li J, Phillips G, Kurukulasuriya NC, Viglietta V. Effect of aspirin pretreatment or slow dose titration on flushing and gastrointestinal events in healthy volunteers receiving delayed-release dimethyl fumarate. Clin Ther. 2015;37:1402–1419.e5.

Pakhomov SV, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, Roger VL. Agreement between patient-reported symptoms and their documentation in the medical record. Am J Manag Care. 2008; 14: 530–539.

Bent S, Padula A, Avins AL. Brief communication: Better ways to question patients about adverse medical events: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006; 144: 257–261.

Atkinson TM, Li Y, Coffey CW, et al. Reliability of adverse symptom event reporting by clinicians. Qual Life Res. 2012; 21: 1159–1164.

Sheftell FD, Feleppa M, Tepper SJ, Rapoport AM, Ciannella L, Bigal ME. Assessment of adverse events associated with triptans: methods of assessment influence the results. Headache. 2004; 44: 978–982.

Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, Moore RA, Collins SL. Reporting of adverse effects in clinical trials should be improved: lessons from acute postoperative pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999; 18: 427–437.

Tornatore C, Amjad F. Attenuation of dimethyl fumarate-related gastrointestinal symptoms with montelukast. Poster presented at: 68th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology; April 26–May 3. 2014; Philadelphia, PA.

Levinthal DJ, Rahman A, Nusrat S, O'Leary M, Heyman R, Bielefeldt K. Adding to the burden: gastrointestinal symptoms and syndromes in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Int. 2013; 2013:319201.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Fox has received financial support for research and speaker's bureau, advisory, or consultation fees from Acorda, Bayer, Biogen, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Opexa, Roche, Sanofi, and Teva. Dr. Vasquez has received compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities from Biogen, Genzyme, Teva, and US World Meds. Dr. Grainger has received financial support for research and speaker's bureau, advisory, or consultation fees from Acorda, Biogen, and Teva. Dr. Ma is an employee of PharmStats, Ltd. Drs. von Hehn, Walsh, Li, and Zambrano are employees of and hold stock or stock options in Biogen.

Funding/Support: This study was funded by Biogen, which reviewed and provided feedback on the paper to the authors and provided medical writing support in the development of the manuscript. The authors had full editorial control of the manuscript and provided their final approval of all content.