Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Frequency of and Factors Associated with a Proxy for Critical Falls Among People Aging with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Background: Critical falls, defined in the literature as involving an inability to get up after the fall, have been associated with morbidity and mortality in older adults but have not been examined in people with multiple sclerosis (MS). To highlight the importance of the critical fall concept in MS, this exploratory study sought to identify the frequency of and factors associated with a proxy for critical falls in people with MS.

Methods: Of 354 adults with MS 55 years and older interviewed, 327 reported a story about their most recent fall that included information about fall-related experiences, including whether they received help to get up after a fall. We used this information as a proxy for critical falls in a logistic regression analysis.

Results: A total of 177 individuals (54.1%) received help to get up after their most recent fall. Logistic regression analysis revealed six factors associated with this proxy for critical falls: fall leading to a fracture (OR = 4.21), leg weakness (OR = 3.12), living with others (OR = 2.48), female sex (OR = 1.96), balance or mobility problems (OR = 1.90), and longer disease duration (OR = 1.04).

Conclusions: Receiving help after a fall is common for people aging with MS, suggesting that critical falls need to be further studied. Findings support the need for fall management education that includes action planning for proper assistance and balance and strength training to increase the ability to get up safely after a fall.

Balance and mobility impairments, leg weakness, fatigue, and cognitive and visual dysfunction are common symptoms in people with multiple sclerosis (MS). These symptoms can be very disabling, can negatively affect independence and quality of life, and can increase the risks of falling.1 A meta-analysis of prospective studies from Australia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States showed that 56% of adults (300 of 537) with MS 18 years or older experienced at least one fall in a 3-month period.2 In comparison, it is well documented that the rate of falls in community-dwelling adults 65 years or older is 30% annually.3 Most importantly, the number of frequent fallers among people with MS is substantial; more than 50% of fallers 18 years or older prospectively reported more than one fall in a 3-month period.4,5 The frequency of falls experienced by people with MS creates an imperative not only to prevent falls but also to understand and better manage the post-fall experience.

Getting up after a fall is a very important component of the post-fall experience. Bloch6 defined the inability to get up unassisted as a critical fall. In community-dwelling adults 65 years or older, critical falls were found to be associated with decline in activities of daily living, cognitive impairment, serious injuries, admission to the hospital, subsequent moves into long-term care,7,8 and even death.6,9 Rising from the floor requires good muscle strength, coordination, balance, and flexibility.10 People with MS commonly experience impairments in one or more of these abilities and, thus, may have more difficulty or take more time to get up after a fall. Nearly 30% of adults with MS need more than 10 minutes to get up after a fall, and this delayed initial recovery is associated with leg weakness, depression, and getting help to get up.11 Because people with MS can experience multiple falls per month,4,5 critical falls may be a marker of more serious physical and psychological consequences and may help identify individuals who are in greater need of intervention. However, no studies to date have reported on the prevalence of critical falls in people with MS.

To shed light on the importance of the critical fall concept in people aging with MS and to guide future investigation of post-fall experiences in this population, a secondary analysis of existing data from a cross-sectional United States–based study was performed. The aim of this exploratory analysis was to determine the frequency of receiving help to get up after a fall (used as a proxy for critical falls) reported by people with MS aged 55 years or older. Factors associated with this proxy were also explored. The first hypothesis was that receiving help to get up after a fall would be experienced by at least 50% of the study participants. The second hypothesis, based on post-fall literature reflecting the experiences of both community-dwelling older adults and people with MS,6–8,11 was that factors associated with the proxy for critical falls would be older age, longer disease duration, presence of balance or mobility problems, leg weakness, depression, and fall leading to a fracture.

Methods

The data used in this study were originally collected to inform the development of an intervention intended to reduce fall risk factors in people aging with MS. A telephone-administered survey was used. The recruitment and sampling methods have been previously described.12,13 The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Defining the Dependent Variable

During the survey, the 354 participants were asked to tell the story about their most recent fall using an open-ended question; 337 did so. The fall stories were read and coded by the lead researcher (EJB) in an effort to identify critical falls. Because participants were not always explicit during their stories about their ability to get up, as per Bloch's6 definition, it was necessary to construct a proxy for a critical fall that reflected what happened after the fall (ie, participant received help to get up). Unclear statements regarding receiving help to get up were identified and subsequently discussed with another author (MF) to determine the most appropriate coding decision.

Ten stories as described by 10 participants did not include any information about getting up after the fall (3.6%); therefore, the proxy for critical fall could not be constructed. Thus, 327 participants were included in the present study. Through the coding process, a dichotomous variable was created and labeled as critical falls–received help (RH). It divided the present sample into two groups: MS fallers who received help to get up after their most recent fall and those who did not.

Measures of Covariates

Covariates of interest were pulled from the regular survey questions and responses and included age, sex, living with others (yes, no), disease duration (years since diagnosis), number of comorbidities, number of mobility aids used (sometimes or regularly), activity curtailment (yes, no), MS status (stable or improving, deteriorating, variable), and several MS symptoms. Information about MS symptoms was collected based on the work of Kersten et al.14 Participants were asked whether each of the following MS symptoms interfered with their daily activities (not a problem, a little, or a great deal): fatigue, balance or mobility problems, leg weakness, depression, pain, vision problems, and poor concentration or forgetfulness. Responses about fatigue, balance or mobility problems, and leg weakness were collapsed to a dichotomous variable “interfering a great deal” (yes = interfering a great deal, no = interfering a little and not a problem) because of low cell counts for the response “not a problem.” Responses on depression, pain, vision problems, and poor concentration or forgetfulness were collapsed to a dichotomous variable “interfering at least a little” (yes = interfering a little and a great deal, no = not a problem) because of low cell counts for “interfering a great deal.”

In addition, covariates related to falls included in this study were fall frequency (less than once a year, more than once a year but less than once a month, once a month or more), fall leading to a fracture (yes, no), fall leading to head trauma (yes, no), fall occurred in the home residence (yes, no), and fall self-efficacy measured using the Fall Efficacy Scale.

Data Analysis

All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Significance was set at P = .05. Fallers who did and did not report a critical fall–RH were compared across all covariates to inform the selection of variables for multivariate analysis. Continuous variables (age, disease duration, number of comorbidities, number of mobility aids used, and fall self-efficacy) were compared using t tests. Categorical variables (sex, living with others, MS status, MS symptoms, activity curtailment, fall frequency, fall leading to fracture, fall leading to head trauma, and fall occurred in the home residence) were compared using χ2 tests.

Covariates that were significant in the univariate analysis were included in the logistic regression model examining factors associated with critical fall–RH. These variables included living with others, disease duration, number of mobility aids used, balance or mobility problems, leg weakness, fall self-efficacy, and fall leading to a fracture. To adjust for age and sex, these variables were entered into the model first. To determine the best-fitting and most parsimonious model, conditional forward stepwise models were compared with conditional backward stepwise models (using a P < .05 criterion for both entry and remaining in the model). The model fit was assessed by the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (P > .05 was considered a good fit).

Results

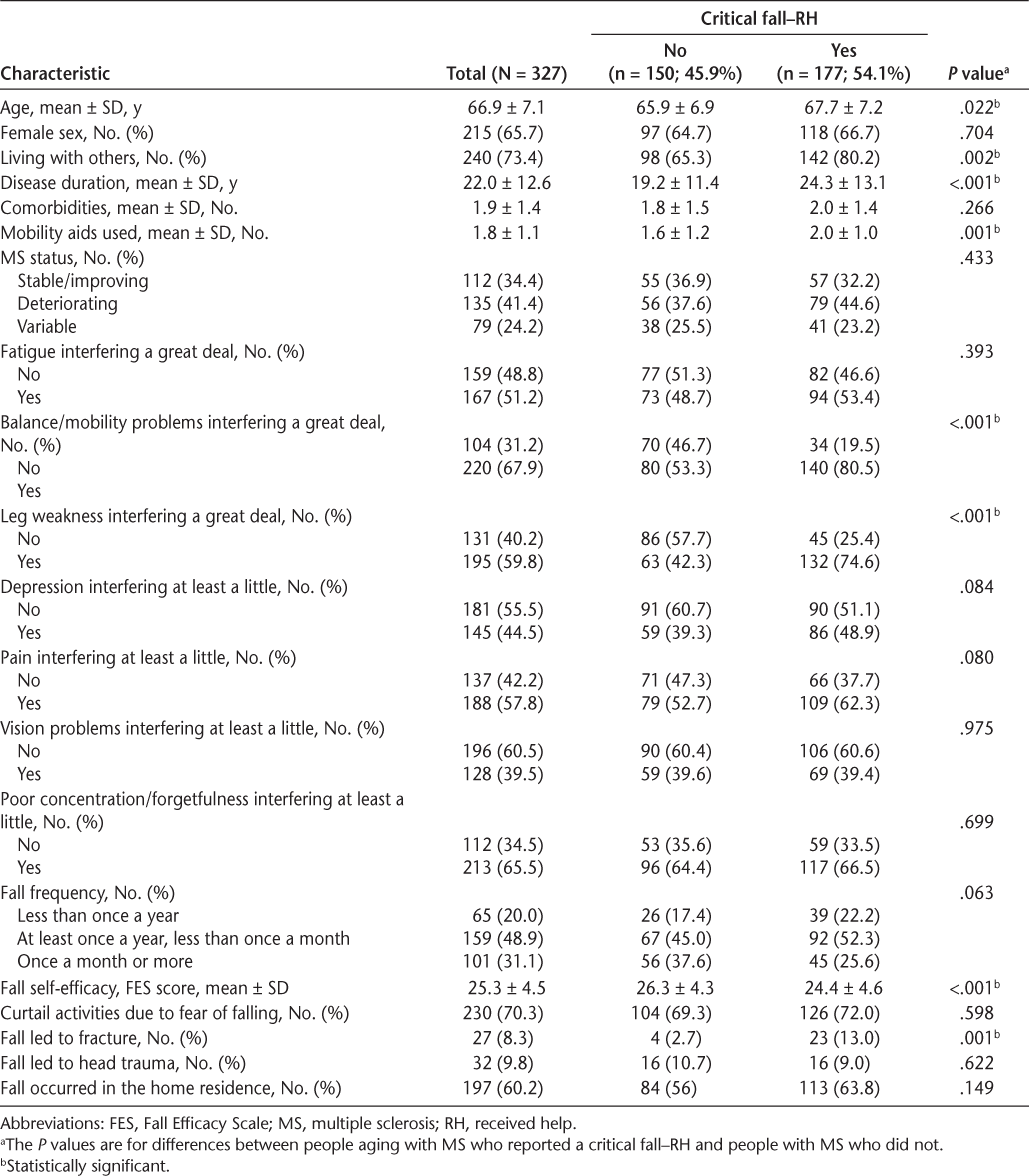

Of the 327 adults with MS aged 55 years and older included in this study, 177 (54.1%) received help to get up after their most recent fall (ie, critical fall–RH). Characteristics of individuals aging with MS who reported a critical fall–RH and those who did not are presented in Table 1. Compared with individuals aging with MS who did not report a critical fall–RH, those who did were slightly older, had MS for 5 years longer on average, and used more mobility aids. A greater proportion of individuals aging with MS who reported a critical fall–RH lived with at least one other person, reported balance or mobility problems, and had leg weakness compared with individuals aging with MS who did not report a critical fall–RH. Fall frequency and activity curtailment were similar between the two groups, but individuals aging with MS who reported a critical fall–RH had lower fall self-efficacy, and a greater proportion of them had a fracture due to their most recent fall, compared with individuals aging with MS who did not report a critical fall–RH.

Characteristics of the study participants

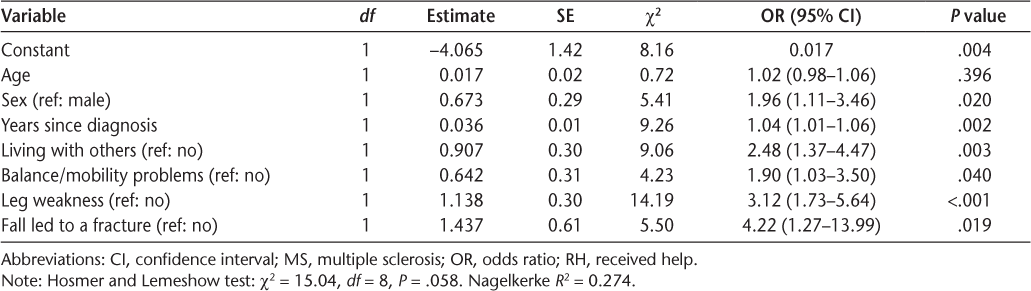

Parameter estimates, odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals, and P values of the final logistic regression model for factors associated with critical fall–RH are shown in Table 2. The final models from the forward and backward stepwise analyses were identical. Six factors were found to be independently associated with critical falls–RH: fall leading to a fracture (OR = 4.21), leg weakness (OR = 3.12), living with others (OR = 2.48), female sex (OR = 1.96), balance or mobility problems (OR = 1.90), and longer disease duration (OR = 1.04).

Results from final logistic regression modeling for critical fall–RH in people aging with MS

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the concept of critical falls in people with MS. The present findings showed that more than 50% of the people with MS aged 55 years or older studied reported receiving help to get up after their most recent fall. Thus, the first hypothesis was supported. The second hypothesis was partially supported. Of the six factors we expected to be independently associated with the proxy for critical falls, four (fall leading to a fracture, leg weakness, balance or mobility problems, and longer disease duration) were found to be significant in the logistic regression. Only age and depression were not associated with the proxy for critical falls as hypothesized. In addition, living with others and being a woman were also found to be independently associated with the proxy for critical falls.

Getting Help After a Fall

Unfortunately, due to the nature of the data used in this study, we could not distinguish between fallers who required assistance to get up (critical fall, as defined by Bloch6) and fallers who received help to get up (the proxy for critical fall). Nonetheless, a substantial proportion of the sample reported that they received help to get up after their most recent fall. Considering that people with MS are frequent fallers,4,5 we would anticipate that the occurrence of critical falls in people aging with MS would be significant. In older adults, critical falls, defined as the inability to get up unassisted, occurred in up to 66% of fallers8 and were associated with decline in activities of daily living, cognitive impairment, serious injuries, admission to the hospital, and subsequent moves into long-term care.7,8 A meta-analysis showed that lying on the floor for a long time after a fall nearly doubles the risk of death in older adults.6

Despite the fact that we used a proxy to capture critical falls, together, the older adult literature and the present findings strongly suggest that providing people aging with MS with the knowledge and skills needed to safely get up from the ground or floor after a fall in a timely manner, with or without assistance, is important. Such interventions could reduce the consequences of falls (ie, long lie, fear of falling, admission to long-term care) in this high-risk population. In addition, critical falls may be used as a marker of more serious physical and psychological consequences and may help identify individuals who are in greater need of intervention.

This identification process must start with careful screening by clinicians. Beyond seeking information about the occurrence of a fall, additional details, such as whether assistance was needed to get up, whether the individual received help to get up, and the amount of time spent on the floor or ground, need to be sought. Studies investigating the association between perception of needing help to get up from a fall and receiving help after a fall are needed. Such studies will support refined operationalization of the term critical fall.

Personal Factors

The present findings indicate that people with MS 55 years and older with leg weakness were three times more likely to report a critical fall–RH, and those with balance or mobility problems were nearly two times more likely to report a critical fall–RH. These findings highlight the need for strength and balance training and education undertaken with the specific aim to help people aging with MS to get up after a fall. Skelton et al.15 showed the effectiveness of a tailored fall management program (including strength, balance, flexibility multitasking exercises, and exercises on how to get up safely) in community-dwelling older women who were recurrent fallers. Similar training was also shown to increase the ability of older adults to get up from the ground.16 These are good examples to consider when developing a fall management intervention specific to MS, although their effect on the prevalence of critical falls is still unknown. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society Free from Falls program includes a 1-hour session on recovering safely from a fall. This 8-week program was recently shown to be effective in increasing balance and mobility and reducing falls,17 but a randomized controlled trial is needed to confirm the efficacy of the program.

The present findings showed that women were two times more likely to report a critical fall–RH than were men. In their study involving 110 adults 90 years or older, Fleming et al.8 found that older women were six times more likely to ask for help to get up after a fall. It is known that women generally have less muscle mass than men,18 and, thus, female fallers with MS may be more likely to seek help due to lower strength compared with male fallers. Women aging with MS may be in greater need of strength training or fall management support to get up after a fall.

Living longer with MS increased the chances of reporting a critical fall–RH by 4% every year in this sample of people with MS. As the disease progresses, the disability of most people with MS increases; the median time from MS onset to a score of 4 (significant disability) on the Expanded Disability Status Scale is 8 years and a score of 6 (disability precluding full daily activities) is 20 years.19 On average, people with MS in this study had MS for 22 years, and less than 10% had MS for less than 8 years. Unfortunately, Expanded Disability Status Scale scores were not available in this study to make this link with disability. However, independent of greater overall disability, longer disease duration was found to increase the risk of fall in people with MS,20 and the present findings showed that this factor also increased the chances of receiving help to get up after a fall.

Altogether, these personal factors could be used by clinicians to identify individuals at higher risk.

Event-Related Factors

The present findings show that people with MS aged 55 years or older living with others were two and a half times more likely to report a critical fall–RH, but given the definition of the proxy measure of critical falls, this is not surprising. The proxy referred to people aging with MS who received help to get up and not necessarily people aging with MS who required assistance. People living with others have greater access to assistance and may get help to get up even if they had the capacity to get up on their own. Nevertheless, people aging with MS living with others are more likely to ask for help, which supports the importance of fall management education for caregivers alongside people aging with MS. This finding also highlights the need to teach people aging with MS how to effectively direct others to assist them after a fall.

Finally, the present findings suggest that serious injuries could be a marker of critical fall. Indeed, people aging with MS who had a fracture due to their most recent fall were four times more likely to receive help to get up. This is not surprising because getting up from a fall with minor injuries is easier than recovering from a fall with a severe injury.21 This finding highlights the importance of identifying people aging with MS who have osteoporosis and, therefore, are at increased risk for fracture. Building the fall management skills of these individuals may be especially important.

Limitations

In addition to using a proxy for critical falls, this study has some limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First, this study was a secondary analysis on cross-sectional data and retrospective reporting of falls; thus, the data and findings may be subject to recall bias. Inaccurate recall of assistance received could have resulted in overcounting or undercounting the number of falls for which assistance was received. Second, the fall stories with information about receiving help to get up referred only to the participant's most recent fall; thus, the critical falls–RH prevalence may have been underestimated. Because most people with MS are recurrent fallers,4,5 it is possible that more people aging with MS may have received help to get up after one or more falls in the past year, but just not the one that was used as the basis for the recent fall story. We also acknowledge that although the model was adjusted for age, the sample included only people with MS aged 55 years or older. Thus, the prevalence and factors associated with critical falls–RH found in this study may be relevant only to this age group. Despite these limitations, this is the first study exploring factors associated with critical falls in people aging with MS and indicates that prospective studies on fall prevention should consider monitoring these types of falls.

Conclusion

More than half of people with MS reported retrospectively receiving help after a fall, suggesting that critical falls in this population may be common. Prospective studies using refined criteria to identify a critical fall are needed to determine whether the prevalence of critical falls in people with MS aged 55 years or older is higher than that in the older adult population.

Factors associated with the proxy for critical falls, such as leg weakness and balance or mobility problems, suggest that physical training could reduce the prevalence and risk of lying on the floor for long periods. Fall-prevention programs should include balance and strength training and education for people aging with MS to increase the ability to get up safely after a fall, consequently decreasing the likelihood of lying on the floor or ground for a long period after a fall. Other factors identified as being associated with the proxy for critical falls in this study, such as being a woman, longer disease duration, and living with others, may guide clinicians to target individuals aging with MS with greater fall management needs. These findings also support the need for fall management education that includes action planning for proper assistance.

PracticePoints

Receiving help to get up after a fall (ie, a proxy for critical fall) is common for people with MS.

People with MS who reported leg weakness or balance and mobility problems were more likely to receive help after a fall and consequently increase their risks of lying on the floor for long periods.

Fall-prevention programs for people with MS should focus not only on preventing falls but also on teaching individuals how to get up safely after a fall with or without assistance.

References

Gunn HJ, Newell P, Haas B, et al. Identification of risk factors for falls in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2013; 93:504–513.

Nilsagard Y, Gunn H, Freeman J, et al. Falls in people with MS: an individual data meta-analysis from studies from Australia, Sweden, United Kingdom and the United States. Mult Scler. 2015; 21:92–100.

Lord S, Sherrington C, Menz H, et al. Falls in Older People: Risk Factors and Strategies for Prevention. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007:7.

Gunn H, Creanor S, Haas B, et al. Frequency, characteristics, and consequences of falls in multiple sclerosis: findings from a cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014; 95:538–545.

Nilsagard Y, Lundholm C, Denison E, et al. Predicting accidental falls in people with multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Clin Rehabil. 2009; 23:259–269.

Bloch F. Critical falls: why remaining on the ground after a fall can be dangerous, whatever the fall. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012; 60:1375–1376.

Tinetti ME, Liu WL, Claus EB. Predictors and prognosis of inability to get up after falls among elderly persons. JAMA. 1993; 269:65–70.

Fleming J, Brayne C; Cambridge City over-75s Cohort study collaboration. Inability to get up after falling, subsequent time on floor, and summoning help: prospective cohort study in people over 90. BMJ. 2008;337:a2227.

De Brito LBB, Ricardo DR, de Araújo DSMS, et al. Ability to sit and rise from the floor as a predictor of all-cause mortality. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012; 21:892–898.

Roorda LD, Roebroeck ME, Lankhorst GJ, et al. Measuring functional limitations in rising and sitting down: development of a questionnaire. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996; 77:663–669.

Bisson EJ, Peterson EW, Finlayson M. Delayed initial recovery and long lie after a fall among middle-aged and older people with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015; 96:1499–1505.

Peterson EW, Ben Ari E, Asano M, et al. Fall attributions among middle-aged and older adults with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013; 94:890–895.

Peterson EW, Cho CC, von Koch L, et al. Injurious falls among middle aged and older adults with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008; 89:1031–1037.

Kersten P, McLellan DL, Gross-Paju K, et al. A questionnaire assessment of unmet needs for rehabilitation services and resources for people with multiple sclerosis: results of a pilot survey in five European countries. Clin Rehabil. 2000; 14:42–49.

Skelton D, Dinan S, Campbell M, et al. Tailored group exercise (Falls Management Exercise–FaME) reduces falls in community-dwelling older frequent fallers (an RCT). Age Ageing. 2005; 34:636–639.

Hofmeyer MR, Alexander NB, Nyquist LV, et al. Floor-rise strategy training in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002; 50:1702–1706.

Hugos CL, Frankel D, Tompkins SA, Cameron M. Community delivery of a comprehensive fall-prevention program in people with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective observational study. Int J MS Care. 2016; 18:42–48.

Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Wang ZM, et al. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr. J Appl Physiol. 2000; 89:81–88.

Confaveux C, Vukusic S, Moreau T, et al. Relapses and progression of disability in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343:1430–1438.

Giannì C, Prosperini L, Jonsdottir J, et al. A systematic review of factors associated with accidental falls in people with multiple sclerosis: a meta-analytic approach. Clin Rehabil. 2014; 28:704–716.

Ryynanen OP, Kivela SL, Honkanen R, et al. Falls and lying helpless in the elderly. Z Gerontol. 1992; 25:278–282.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (Mentor-based Post-doctoral Fellowship in Rehabilitation Research) and by the Retirement Research Foundation (grant RRF 2004-065).