Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Development of a Bilingual MS-Specific Health Classification System

Objective: The global aim of this study was to contribute to the development of the Preference-Based Multiple Sclerosis Index (PBMSI). The specific objective of this foundational work was to qualitatively review the items selected for inclusion in the PBMSI using expert and patient feedback.

Methods: Cognitive interviews were conducted with patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) in English and French. The verbal probing method was used to conduct the interviews. For each PBMSI item, the interviewer probed for specific information on what types of difficulty participants had with the item and the basis for their response for each item. Furthermore, respondents were asked to provide information on the clarity of the item, the meaning of the item, the appropriateness of the response options, and the recall period. All interviews were recorded using a digital voice recorder and were transcribed onto a computer.

Results: The mean age of the 22 respondents was 52 years, and 82% were women. Mean time since diagnosis was 12 years, and the highest level of education completed was university or college for 86% of the sample. Modifications were made to each item in terms of recall period, instructions, and phrasing.

Conclusions: Patient and expert feedback allowed us to clarify items, simplify language, and make items more uniform in terms of their instructions and response options. This qualitative review process will increase accuracy of reporting and reduce measurement error for the PBMSI.

The US Food and Drug Administration's guidelines for the development of patient-reported outcomes requires patient input in the development of self-reported assessments.1 Conducting cognitive interviews with patients is important when developing questionnaires to help reduce respondent burden and minimize measurement error.

Preference-based measures are patient-reported outcomes of health-related quality of life that are commonly used for economic evaluation in health care.2 They are usually developed using multiattribute utility theory, consist of one item per dimension, and provide a single value of health-related quality of life from 0 (death or worst possible health state) to 1 (perfect health or best possible health state).3 Preference-based measures can often generate hundreds and thousands of health states. The most commonly used preference-based measure is the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D), which consists of five items: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain, and anxiety/depression.4 Each item has three response options, providing a total of 243 (35) unique health states. The EQ-5D is self-administered and takes 1 to 2 minutes to complete.2 Recently, a five-level version of the EQ-5D has also been developed by the EuroQol group defining a total of 3125 possible health states.5

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that can produce a range of symptoms, such as muscle weakness, fatigue, and cognitive impairment.6 In MS, the use of preference-based measures is limited to generic measures, such as the EQ-5D. However, the challenge with using such generic preference-based measures in MS is that these measures may not capture all domains of health relevant to the disease. Previous work has shown that there are limitations with the use of these measures in MS regarding content and construct validity.7 8 Therefore, an MS-specific preference-based measure may be more appropriate for use in the economic evaluation of treatments involving MS.

In a previous study,9 we identified five items that were most important to the quality of life of people with MS: walking, fatigue, mood, cognition, and work. These five items came from various existing questionnaires.9 As a result, each one of these items had different recall periods, instructions, and response options. This study describes the qualitative review process undertaken to revise these items, in English and French, based on two key sources: expert opinion and patient interviews. This qualitative process will ensure that the items are comprehended and interpreted as intended by patients and are more uniform regarding their instructions and response options.

Therefore, the global aim of this study was to contribute to the development of the Preference-Based Multiple Sclerosis Index (PBMSI). The specific objective of this foundational work was to qualitatively review the five items selected for inclusion in the PBMSI using expert and patient feedback.

Methods

Domain Generation and Item Selection

The methods for domain generation and item selection for the PBMSI have been reported previously.7 9 Briefly, the domains for the PBMSI were created based on semistructured interviews with 185 patients with MS. Patients were asked to identify the most important aspects of their lives that were affected by MS.

These same patients were also asked to complete a comprehensive questionnaire package consisting of more than 200 items from existing patient-reported outcomes or created from scratch by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians and researchers. The items for the PBMSI came from this questionnaire package. Modern methods of measurement (ie, Rasch analysis) were used to select one item per domain.9

Revision and Rewriting of Items

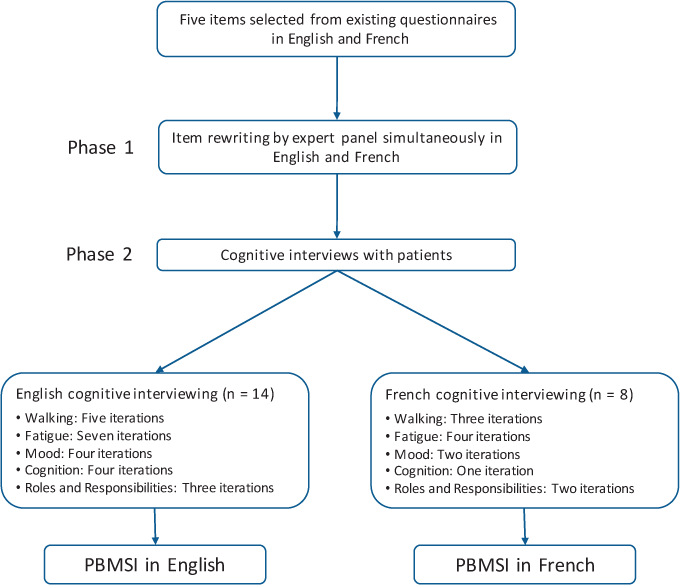

The items selected for inclusion in the PBMSI had different phrasing styles and recall periods. Owing to these variations, the items needed to be rewritten for uniformity and coherence. As presented in Figure 1, item revision was conducted in two phases. The first phase involved item revision and rewriting by experts simultaneously in English and French. In the second phase, the items were cognitively debriefed with 22 patients with MS, 14 in English and 8 in French. During the cognitive interview process, each item went through several iterations before being accepted as the final version included in the PBMSI.

A summary of the simultaneous development of the Preference-Based Multiple Sclerosis Index (PBMSI) items in English and French

Phase 1: Focus Group with Experts

A focus group was conducted with experts in the field of MS to rewrite items that would convey the same information in English and French. Experts were recruited from the four major hospitals in Montreal, Canada (Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal General Hospital, Montreal Neurological Institute, and Notre Dame Hospital).

The focus group was conducted in a roundtable format, where participants were paired up with the person sitting next to them. Each pair was given a copy of the PBMSI items at the start of the session and was asked to discuss each item in terms of the following four points: 1) Is the wording clear and appropriate for the item? If no, how would you change it? 2) Are the response options clear and appropriate for the item? If no, how would you change them? 3) How difficult would it be for patients to answer the question? 4) Do you have any suggestions to improve the item? During the focus group, continual rewording of the items in English and French was conducted so that their interpretations would be the same in both languages. In other words, wording in the two languages was performed in parallel. While items were being rewritten in English, wording in French was suggested by French-speaking researchers, and problematic wording was addressed in both languages. For example, if a wording was suggested in English that would not work in French, then it would be abandoned (eg, hiking, household). The end product was a set of items with parallel English and French wording.

Phase 2: Cognitive Interviews with Patients

Recruitment of Patients. Participants were recruited through advertising on the MS Society of Canada's website, during the 2012 Quebec Summit on MS, and through flyers placed at the outpatient MS clinic of the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital. Interested participants contacted the study coordinator (AK) by e-mail or telephone, and the study coordinator sent the consent form to be signed and returned. Patients were eligible to participate in the cognitive interview if 1) they were diagnosed as having MS, 2) they were at least 18 years of age, and 3) they were able to speak and read English or French. Ethics approval was obtained before study commencement and recruitment.

Cognitive Interviewing Process. Interviews were conducted by two physiotherapists, who were also doctoral candidates with training in patient-reported outcomes and cognitive interviewing. Each interview took approximately 30 minutes to complete. One physiotherapist conducted the English interviews, and the other conducted the French interviews. All the interviews were conducted by telephone.

Before the telephone interviews, participants were sent a questionnaire package with basic sociodemographic questions, the PBMSI questions, and a visual analogue scale of their health state today. Participants were not required to read over the questionnaire package before the interview but were allowed to do so if they wanted to. They were asked to have the package on hand for the interview. During the interview, respondents were first asked to provide their answers to the sociodemographic questions and the PBMSI items. After this, the cognitive interview process for each item began.

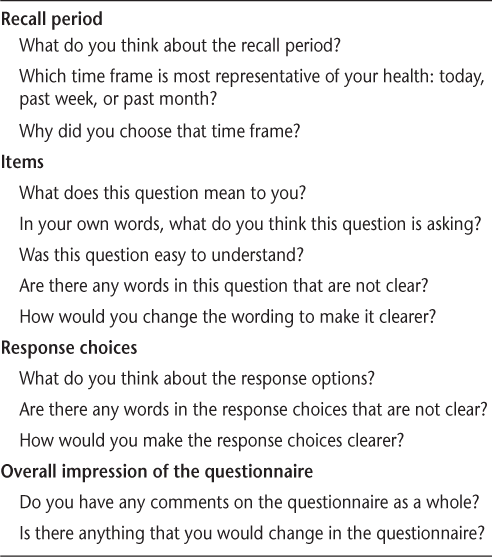

The verbal probing method was used because it is known to help facilitate the interview process and to place less burden on the respondent. As shown in Table 1, for each PBMSI item, the interviewer probed for specific information on what types of difficulty the participant had with the item and the basis for their response for each item. Furthermore, the respondent was asked to provide information on the clarity of the item, the meaning of the item, the appropriateness of the response options, and the recall period.

Cognitive interview questions

To minimize respondent burden, each participant was interviewed on two to three items only. All the interviews were recorded using a digital voice recorder and were transcribed onto a computer.

While the English interviews were taking place, simultaneous rewording of the items in French was being conducted by members of the research team. Once all the items were endorsed or finalized by patients in English (no changes suggested by a minimum of three consecutive people), cognitive interviews were also performed on the French items. The same format and type of questions that were used during the English interviews were also used during the French ones. The French-speaking interviewer asked the respondent about the meaning of specific words in the item, the overall meaning of the item, and why he or she had chosen a specific response option. For some items, the respondent was also asked to consider alternative wording for those items.

Analysis of Cognitive Interview Data. After each interview, the interviewer reviewed the comments to determine issues with recall period, comprehension, clarity, and response options. If an item was found to be problematic during the interview, it was revised based on the respondents' suggestions and then tested on the next respondent. When at least three respondents in a row stated that they had no problems with an item, the item was accepted as the final version.

Results

The focus group consisted of 24 clinicians and researchers, including a neurologist, a clinical psychologist, a neuropsychologist, an epidemiologist, 11 physiotherapists, 3 occupational therapists, 1 nurse, and 5 graduate students. All the participants had experience working with patients with MS or other neurologic conditions, such as stroke.

During the focus group, it was decided that similar to the EQ-5D, the recall period would be based on the patient's “health state today.” Therefore, statements such as “past 4 weeks” were removed from the items. Item 5 on “ability to work” was revised to “roles and responsibilities” to include patients who did not work but performed work-related activities, such as housekeeping. Response options were also simplified, and unnecessary wording was removed to reduce the cognitive burden on the patients.

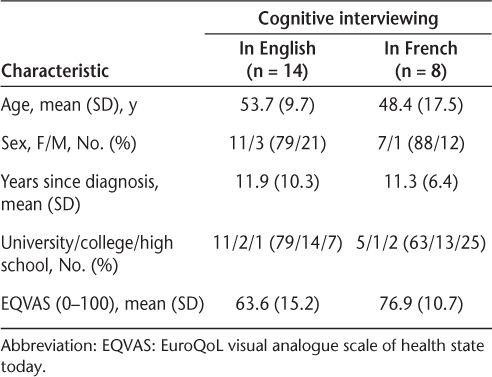

Once the items were reviewed and finalized among the experts, they were then taken to the patients for cognitive interviewing. Table 2 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients who participated in the cognitive interview. There were 14 and 8 participants who underwent cognitive interviewing in English and in French, respectively. The English cognitive interview participants, compared with the French cognitive interview participants, were slightly older and consisted of a greater proportion of men. However, the mean number of years since diagnosis was the same for both groups (11 years).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cognitive interview patients

Supplementary Table 1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org, presents the step-by-step changes that were made to each item in English during the cognitive interview process. Each item underwent several iterations: five for walking, seven for fatigue, four for mood, four for cognition, and three for roles and responsibilities. The changes are explained in detail in the following subsections.

Walking

The item on walking was revised to include people with high levels of physical function (ie, individuals who could walk briskly for recreation or sports). Furthermore, certain words, such as community, were removed because patients found them to be too vague or ambiguous.

Fatigue

In the original version, fatigue was described as “exhausted.” However, patients found this to be a “heavy” word. In fact, one patient stated that if fatigue were on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 was fatigue, exhaustion would be a 10. Therefore, as per patients' suggestions, the word exhaustion was removed from the item. When patients were asked how they would describe MS-related fatigue, they expressed that the need to rest should be incorporated into the item. Therefore, the response options were revised to “I never felt so tired that I had to rest. . . I felt so tired that I had to rest one or more times throughout the day. . . I felt so tired that I had to rest most of the day.”

Mood

A small yet important modification was made to the mood item as a result of feedback from patients. The original response levels for this item were “I did not feel sad . . . I felt somewhat sad . . . I felt very sad.” Patients reported that the word depressed should be incorporated into the response options because it was not clear that the question was referring to depression. Therefore, the response levels were revised to “I did not feel sad or depressed . . . I felt somewhat sad or depressed . . . I felt very sad or depressed.”

Cognition

The aspect of cognition assessed in the PBMSI was decision making (eg, planning your day, planning meals, etc.). However, when patients were interviewed on this item they reported having no problems with decision making. Instead, patients stated that concentration was an area of cognition that was a major concern for them. As a result of this feedback, the cognition item was changed to “concentration” and was phrased as, “Did you have trouble concentrating in the past week (on things like conversations, books, movies, or daily routines)?”

Roles and Responsibilities

Very minor changes were made to the response levels of this item. Generally, patients stated that roles and responsibilities as described by “ability to do the things you needed to do at work, at home, and to take care of yourself and your family” was clear and easy to comprehend.

Recall Period

Because MS has an unpredictable course and symptoms can change from day to day, patients reported that “today” was not an accurate representation of their symptoms. Patients stated that “during the past week” was an appropriate time frame because it was more representative of their experience and easy to recall. Patients stated that the recall period “during the past month” was difficult to remember.

Supplementary Table 2 presents the step-by-step changes that were made to each item in French during the cognitive interview process. The walking item underwent three iterations, fatigue underwent four iterations, mood underwent two iterations, cognition underwent one iteration, and roles and responsibilities underwent two iterations. Examples of changes include “la plupart du temps” being revised to “le plus souvent,” and “que j'ai eu” being revised to “au point où j'ai eu.” Supplementary Table 3 presents a summary of the items 1) in their original version, 2) after being rewritten by experts in the focus group, and 3) at the end of the cognitive interviews. Supplementary Table 4 presents the same items in French.

The PBMSI Questionnaire

A copy of the PBMSI questionnaire (in English and French) can be found in Appendix 1.

Discussion

This study described the development of a bilingual MS-specific health classification system, the PBMSI. Experts in the field of MS were brought together in a focus group to rewrite items simultaneously in English and French. The purpose of the focus group was to clarify confusing items, to simplify language, and to ensure that there was consistency in the style of the questions and response options. Forward-backward translation of the items was not necessary because the items were developed simultaneously in both languages at the expert level. Later, cognitive interviews were conducted with 14 English-speaking and 8 French-speaking patients. Based on patient feedback, revisions were made simultaneously in both languages to each item in terms of content, instructions, and phrasing.

Two well-known methods of developing questionnaires in multiple languages are sequential and simultaneous.10 In the sequential approach, items are developed in only one language (the source language), with subsequent translation into the target languages using a forward and backward translation process. In the simultaneous approach, native speakers from each language develop items simultaneously. The PBMSI items were developed at the expert level (ie, focus groups) using the latter approach. The advantage of the simultaneous method compared with the sequential method is that any problematic wording and discrepancies between the language versions are resolved during the item-generation process.10 After item writing at the expert level, we conducted cognitive interviews with patients to ensure that there was semantic and conceptual equivalence between languages. We assessed whether patients understood the questions the same way in both English and French.

The study sample size was similar to that of other studies that involved cognitive interviews to develop questionnaires. The present sample size of 22 patients was sufficient and within the recommended range in the literature. Willis11 recommended that samples of 5 to 15 individuals were sufficient when revising questionnaire items. Also, Sheatsley12 suggested that it usually takes no more than 12 to 25 interviews to reveal major flaws in a questionnaire.

Furthermore, the method we used to conduct the cognitive interviews, verbal probing, is a well-established and accepted method.13 The use of probing helps guide the respondent and shapes the interchange in a way that is controlled mainly by the interviewer. The advantages of this method are that it helps avoid irrelevant or unnecessary discussion during the interview and helps the interviewer concentrate on areas that seem to be important sources of error.11 13 The alternative method, which is the think-aloud method, also has its own advantages. For example, minimal interviewer training is required because the interviewer is required to mainly listen to the respondent talk. Furthermore, because minimal guidance is provided, the respondent or patient may provide information that is unanticipated by the interviewer. However, the disadvantage of the think-aloud method is that all the respondents may not be outgoing and elaborate very much on a question. Also, this method places a significant amount of burden on the respondent and may result in the individual wandering off track and delving into unrelated topics.11 13

We were sensitive to avoid wording that could be subjected to response shift. Response shift is defined as a change in one's evaluation of a target construct (ie, fatigue) as a result of a change in the respondent's internal standards of measurement, values, and conceptualization of the target construct.14 Difficulty is a word that has been flagged as a potential source for response shift because patients may recalibrate how they interpret what difficulty means to them over time.15 In the PBMSI, the only item that would be close to being subjected to response shift would be concentration, which used the word trouble. However, in the context of this item, the word trouble was used as a noun and not as an adverb to describe difficulty.

The choice of recall period can depend on the disease or the condition's characteristics.1 In this study, based on feedback from patients, a 7-day recall period was used for the PBMSI items. Because MS has an unpredictable disease course and symptoms can vary from day to day, a recall period using the “past week” was found to be most appropriate. Asking patients to answer a question based on their health state “today” would not be an accurate representation of their experiences. As one patient pointed out, symptoms such as fatigue can vary not only from one day to the next but also within a single day (ie, morning to afternoon). Also, to avoid having patients average their responses over the past week (because it can undermine content validity),1 we asked patients to select a response based on the state that they were most often in during the past week. For example, the response options for the question, “Describe your fatigue in the past week” were “Most often . . . (i) I never felt so tired I had to rest, (ii) I felt so tired I had to rest one or more times throughout the day, (iii) I felt so tired I had to rest most of the day.” A time frame of “in the past month” was disapproved by patients because it was a long time to remember, and it was likely to be influenced by their state at the time of recall.

A strength of this study was that the items went through several processes of review to ensure that they were clear and easy for patients to understand. Furthermore, the sample of patients with MS not only was of a sufficient number but also was representative of various age groups and disease characteristics (ie, number of years since diagnosis ranged from 1 to 38 years).

A limitation of this study was that all the items were changed from their original format, and as a result the items may function differently. However, these changes were made to make the items more uniform and easy for interpretation by patients. We believe that the methods of qualitative review conducted in this study did not worsen the items but rather improved them in terms of phrasing and clarity.

The process of qualitative review was an important and necessary step to produce the best items for use in the PBMSI. Item writing by experts and cognitive interviews with patients allowed us to clarify items, simplify language, and make the items more uniform in terms of their instructions and response options. This method, in the future, will not only help minimize unnecessary cognitive burden on patients when filling out the questionnaire but also increase the accuracy of reporting. The next step in the development of the PBMSI will be to elicit patient preferences for each of the items using standard valuation methods and to calculate a scoring algorithm for the index.

PracticePoints

Preference-based measures are patient-reported outcomes of health-related quality of life that are used in clinical and cost-effectiveness research. They provide a single value for health-related quality of life from 0 (death or worst possible health state) to 1 (perfect health or best possible health state).

This study developed a bilingual preference-based measure for MS, the Preference-Based Multiple Sclerosis Index (PBMSI), through focus groups with experts and cognitive interviews with patients.

This qualitative review process was necessary to reduce respondent burden and minimize measurement error in the PBMSI.

The next step will be to elicit patient preferences for each of the items using standard valuation methods and to calculate a scoring algorithm for the index.

References

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Federal Register. 2009;74:65132–65133.

Feeny D. Preference-based measures: utility and quality-adjusted life years. In: Fayers P, Hays R, eds. Assessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2005:405–429.

Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, et al. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the health utilities index mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002;40:113–128.

Kind P, Brooks R, Rabin R. EQ-5D Concepts and Methods: A Developmental History. New York, NY: Springer; 2006.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–1736.

Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:938–952.

Kuspinar A, Mayo NE. Do generic utility measures capture what is important to the quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:71.

Kuspinar A, Mayo NE. A review of the psychometric properties of generic utility measures in multiple sclerosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:759–773.

Kuspinar A, Finch L, Pickard S, Mayo NE. Using existing data to identify candidate items for a health state classification system in multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1445–1457.

Marquis P, Keininger D, Acquadro C, de la Loge C. Translating and evaluating questionnaires: cultural issues for international research. In: Fayers P, Hays R, eds. Assessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2005:77–93.

Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005.

Sheatsley PB. Questionnaire construction and item writing. In: Rossi PH, Wright JD, Anderson AB, eds. Handbook of Survey Research. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1983.

Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:229–238.

Schwartz CE, Sprangers MA. Methodological approaches for assessing response shift in longitudinal health-related quality-of-life research. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1531–1548.

Barclay-Goddard R, Lix LM, Tate R, Weinberg L, Mayo NE. Health-related quality of life after stroke: does response shift occur in self-perceived physical function? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92: 1762–1769.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.