Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

A Topical Adhesive Containing Anesthetic and Heating Components to Reduce Injection Pain with Subcutaneous Multiple Sclerosis Medications

Background: Injection pain and fear of pain are common with subcutaneous medications for treating multiple sclerosis (MS). Synera is a peel-and-stick topical adhesive (S-TA) with a novel heating component to enhance the delivery of an anesthetic mixture of lidocaine and tetracaine. We studied the effect of S-TA on pain and other aspects of comfort after subcutaneous MS drug injection.

Methods: Thirty participants with MS having injection reactions to subcutaneous interferon beta (IFNβ) or glatiramer acetate (GA) were enrolled in an open-label prospective study. We captured six to seven injections at baseline and with 60- and 30-minute S-TA application times. The primary outcome was immediate pain on injection. Secondary outcomes included 12- and 24-hour pain ratings, 24-hour local injection-site reaction scale scores, 24-hour tenderness, and fear of injection (FOI).

Results: Twenty-nine participants completed the study (interferon beta = 4, GA = 25, mean age = 51 years, females = 86%). There were significant reductions in injection pain, pain at 12 and 24 hours, tenderness at 24 hours, local injection-site reaction scale scores, and FOI for the 30- and 60-minute applications of S-TA (all P < .01). Results were similar in the GA subgroup. Adverse events included muscle spasm and lightheadedness (n = 1) and mild dermatitis (n = 1).

Conclusions: These results suggest that S-TA applied 30 or 60 minutes before MS drug injection may reduce pain, tenderness, and FOI. Randomized controlled studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of ST-A.

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease afflicting more than 400,000 Americans, may be treated with several medications that require subcutaneous or intramuscular injection. Pain and other local injection-site reactions (LISRs), including pruritus and erythema, are common. A survey of 1380 patients with MS found that at least 94% of users of subcutaneous interferon beta (IFNβ) or glatiramer acetate (GA) had LISRs. Reactions were deemed to be “discomfort” (itching, pain, lumps, dimpling, and skin sores) by 91%, 78%, and 90% of those using subcutaneous IFNβ-1a, subcutaneous IFNβ-1b, and GA, respectively.1 Being female, younger, and nonwhite were factors associated with worse LISRs. Injection-site reactions may cause nonadherence and are among the most common reasons for discontinuation of therapy with IFNβ and the most common reason for discontinuation of GA use according to one study.2

Relieving injection-site pain may improve tolerability of MS medications. There are no US Food and Drug Administration–approved medical treatments for the specific indication of reducing injection pain or injection reaction to any MS medication, but the most common interventions are use of an autoinjector and injection with a smaller-gauge needle. Autoinjector devices are now available for all of the subcutaneous MS medications and are used by approximately half of the patients, with the remainder using a manual syringe injection technique.3 Other proposed methods include topical hydrocortisone, topical lidocaine/prilocaine cream, oral antihistamine, use of skin cooling with ice, heating with warm compresses, and topical herbal products.4–7

Synera topical adhesive (S-TA; Galen US Inc., Souderton, PA) is a peel-and-stick patch containing an anesthetic mixture of lidocaine 70 mg and tetracaine 70 mg. It also has a patented heat-assisted drug delivery system. Once removed from the packaging and exposed to air, the patch heats up to warm the skin and enhance drug delivery. This adhesive is approved in the United States for use in dermal analgesia for superficial venous access and for superficial dermatologic procedures. It may be useful in reducing MS drug injection pain and needle phobia. The approved period of application for venipuncture is 20 to 30 minutes, although a longer period, such as 60 minutes, may be more effective. This was the first study to assess the effect of S-TA on pain with injectable subcutaneous IFNβ and GA in MS. We hypothesized that 60- and 30-minute applications will have similar favorable analgesic effects.

Methods

Patient eligibility required a confirmed diagnosis of MS based on the McDonald criteria, no exacerbation within 60 days, age older than 18 years, stable use of one of the studied MS medication treatments (IFNβ subcutaneous or GA subcutaneous), an LISR scale mean score of at least 1.0, and a pain on injection mean score of at least 3.0 (0–10 scale) at baseline. Patients with a contraindication or allergy to lidocaine, tetracaine, or para-amino benzoic acid–containing products and patients who were pregnant, breast-feeding, or medically unstable were excluded. The study was approved by the research committee at EvergreenHealth Medical Center (Kirkland, WA) and by an external institutional review board (Western Institutional Review Board, Puyallup, WA). Participants were enrolled in the context of clinical care at the EvergreenHealth MS Center through patient education programs, postings at the center's website, ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01834586), and the website of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

At screening, participants gave informed consent and were instructed how to record outcomes information in their diaries in relation to their subcutaneous MS drug injections. Participants returned in 1 to 2 weeks as needed to ensure that they had at least six injection recordings and to complete screening assessments. Qualifying participants received study medication (S-TA). They were instructed to apply S-TA for 60 minutes before each MS drug injection and to remove the adhesive before injecting at the same location. They switched to a 30-minute application time after 2 weeks if taking IFNβ or GA 40 mg (administered 3× per week) and after 1 week if taking GA 20 mg daily. They continued 30-minute treatments for a similar number of injections (1–2 weeks) and returned for a final visit at the end of active treatment to review their diaries, complete questionnaires, and assess for any adverse events (AEs).

The primary efficacy measure was pain on injection, recorded immediately after injection on a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 10. Secondary outcomes included 12- and 24-hour pain ratings (0–10 VAS), LISR scale scores 24 hours after injection (0–6, see the study by Jolly et al.7), fear of injection (FOI) immediately before injection (0–10 VAS, 0 = no fear and 10 = extreme fear), tenderness at 24 hours (0–10 VAS, 0 = no tenderness and 10 = extreme tenderness), Subject Global Impression (SGI; level of comfort with injections during the past week, 1–7 VAS, 1 = terrible and 7 = delighted), participant rating of 60- versus 30-minute application times, and participant rating of interest in using the patch. Except for participant rating of 60- versus 30-minute application times, all testing was performed at baseline and at the end of 60- and 30-minute study periods. Safety was assessed by AE monitoring.

Statistical analyses were performed using the t test (probability [PR] > |t|) for parametric results and the signed rank test (PR ≥ |S|) for nonparametric results. The null hypothesis was that the mean or median change was zero. A P ≤ .05 was judged as having statistical significance. The number of participants was predefined based on the expected capacity for enrollment.

Results

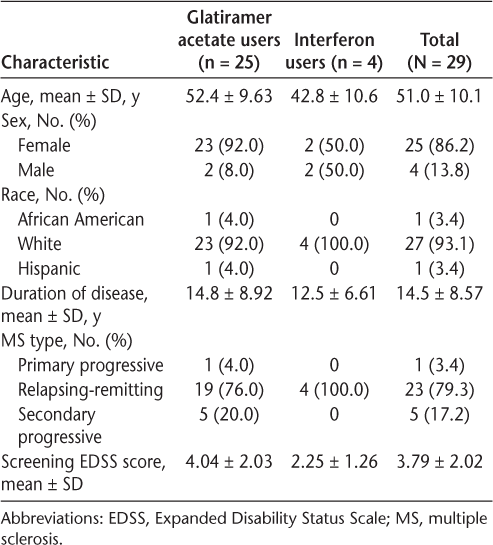

Thirty participants were enrolled, with seven screen failures due to low pain scores (n = 5), withdrawal of consent (n = 1), and an incomplete diary (n = 1). One participant withdrew early, and 29 participants completed the study and had data available for efficacy analyses: 19 taking GA 20 mg, 6 taking GA 40 mg, and 4 taking IFNβ (3 taking IFNβ-1a subcutaneous and 1 taking IFNβ-1b subcutaneous). For participants who completed the study, the mean age was 51 years, 86% were women, 79% had relapsing-remitting MS, and the mean Expanded Disability Status Scale score was 3.8 (Table 1). Adherence to S-TA therapy was 98.4% based on returned supply counts.

Baseline demographic characteristics of the 29 participants who completed the study

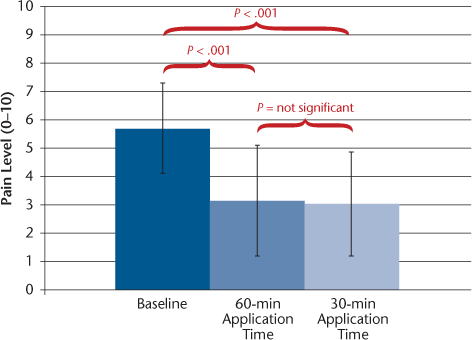

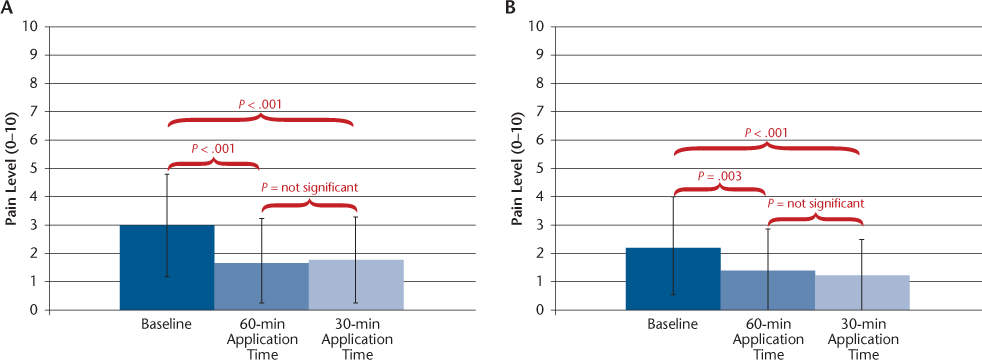

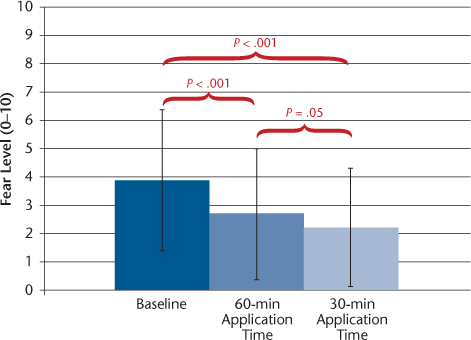

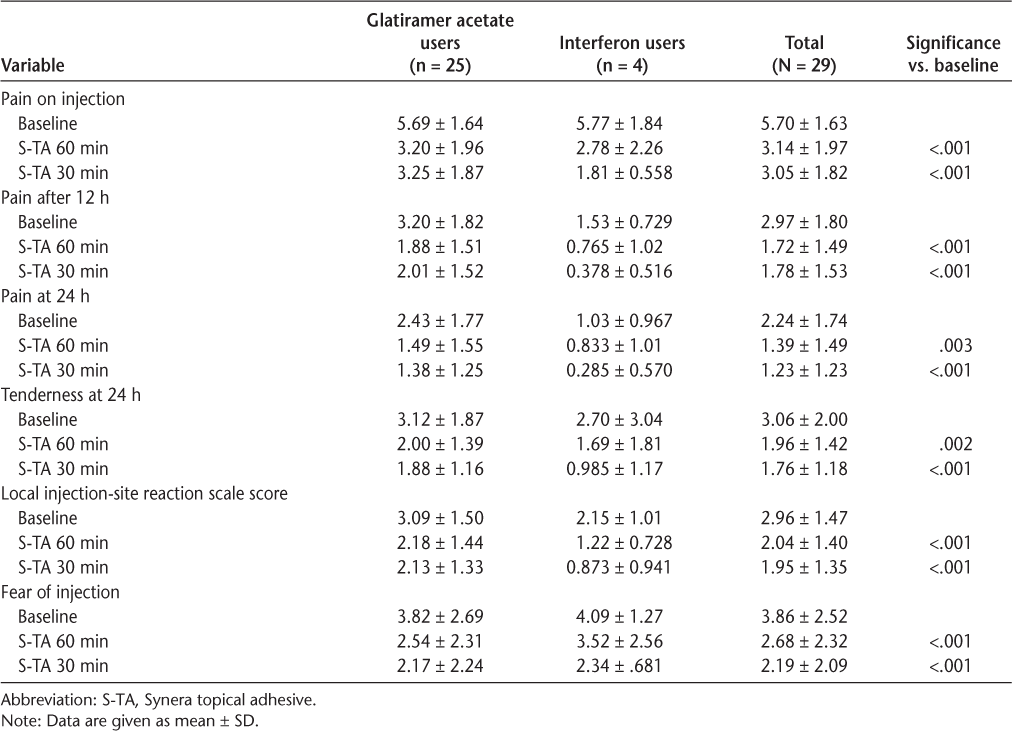

The efficacy results are shown in Table 2. Because the number of participants taking IFNβ was small, all the statistical analyses and further reports are based on the results of all the participants combined. Subgroup analysis showed similar results for the GA group (n = 25, data not shown) compared with results for the total cohort. On the primary outcome measure, pain on injection, the mean VAS score declined by 46% and 47% (from 5.7 to 3.1 and 3.0) with the 60- and 30-minute S-TA application times, respectively, significant reductions for both (P < .001) (Figure 1). Pain reductions at 12 hours were −42% and −40% with the 60- and 30-minute S-TA application times, respectively (P < .001 for both application times) (Figure 2A). Pain reductions at 24 hours were −38% and −45% with the 60-minute (P = .003) and 30-minute (P < .001) S-TA application times (Figure 2B). Differences between the two administration times were not significant for these outcomes. Tenderness ratings at 24 hours were significantly lower with treatment (−36%, P = .002 for 60 minutes; −42%, P < .001 for 30 minutes), and LISR scale scores were −31% for 60 minutes and −34% for 30 minutes (P < .001 for both application times). Neither of these outcomes showed significant differences between the 30- and 60-minute application times. The FOI was significantly reduced (−31%, P < .001 for 60 minutes; −43%, P < .001 for 30 minutes) (Figure 3). The FOI was significantly less with S-TA times of 30 minutes versus 60 minutes (P = .05).

Mean ± SD visual analogue scale scores for pain on injection at baseline and with 60- and 30-minute Synera topical adhesive application times

Mean ± SD visual analogue scale scores for pain at 12 (A) and 24 (B) hours at baseline and with 60- and 30-minute Synera topical adhesive application times

Mean ± SD visual analogue scale scores for fear of injection at baseline and with 60- and 30-minute Synera topical adhesive application times

Efficacy results for the 29 participants who completed the study

We also asked participants to rate global impression (SGI, level of comfort with injections, see the “Methods” section), level of interest in the continued use of S-TA, and preference for 30- or 60-minute application times (data not shown). The SGI score was best for the ST-A 60-minute application time, improving from a mean of 3.6 at baseline to 5.3 (P < .001 vs. baseline). The SGI score difference between the 60- and 30-minute application times was not significant (P = .1). Level of interest in continuing S-TA treatment was best after the 60-minute application time (very interested = 31%, not interested = 14%) and declined after the 30-minute application time (very interested = 24%, not interested = 40%). When asked whether they preferred 60- or 30-minute application times, 48% of participants favored 60 minutes, 41% favored 30 minutes, and the others had no preference.

All AEs were recorded among participants who took at least one dose of study medication (N = 30). Two treatment-related AEs were recorded. One was a moderate AE involving muscle spasm and lightheadedness that occurred on three applications, beginning 5 minutes after applying the patch and lasting up to 3 days on the third occurrence. This led to treatment discontinuation. The other AE was mild application-site dermatitis, which resolved while the participant continued and completed the study. Both of these participants were taking GA. There were no serious AEs and no relapses.

Discussion

There are currently seven approved MS medications for home injection in the United States. Injection pain is a common adverse effect of these injections. The FOI may result from painful injection experiences and may hinder ongoing treatment adherence. This study used a topical adhesive, S-TA, containing a heating element and lidocaine and tetracaine applied immediately before MS drug injection. The treatment window was six to seven injections with the S-TA application time of 60 minutes and then repeated for six to seven injections with the application time of 30 minutes. We measured the effect of S-TA on pain and FOI. Significant reductions were found with both 30- and 60-minute applications of S-TA for pain immediately after injection, which was the primary outcome, and also for pain at 12 and 24 hours.

The primary outcome found pain-on-injection reductions of 2.6 (46%) and 2.7 (47%) on the 11-point VAS with 60- and 30-minute S-TA application times, respectively. Twelve- and 24-hour pain reductions were lower, but still greater than 35% with both 60- and 30-minute applications. The FOI was significantly reduced and SGI scores were significantly improved for both application times, suggesting that changes in pain ratings were meaningful. Two studies of patients with various painful conditions suggested that 30% to 33% changes in pain intensity or 2-point reductions in the raw change on an 11-point pain scale may be regarded as clinically meaningful.8,9 However, meaningful change criteria do not exist specifically for injection pain.

The mechanism by which S-TA reduces injection pain is believed to be the anesthetic components. Both lidocaine and tetracaine stabilize neuronal membranes by inhibiting the ionic fluxes required for the initiation and conduction of impulses, thereby effecting local anesthetic action. Patients typically experience numbness of the skin at the application site that lasts more than 1 hour after removal of the adhesive. The S-TA is approved for other painful procedures (venipuncture, superficial dermatologic procedures), and other lidocaine creams and adhesives have been approved as topical anesthetics. Also, S-TA has a heating element intended to cause hyperemia to the skin and to increase the speed and extent of anesthesia. It is possible that the heating itself plays a role in reducing pain, although heat application with a warm compress before injection did not reduce pain in another study.7 The effect of lowering the FOI may also have contributed to the pain reductions, which could be further assessed through a placebo-controlled trial.

This study also found reductions in tenderness and LISR scale scores at 24 hours, after the anesthetic effect would have worn off. Possible explanations include that the initial effect on pain produced a bias toward lower subjective ratings of non–pain-based elements of the injection reaction, that the heating element promoted drug dissipation that reduced the reaction, or that lidocaine resulted in vascular effects to reduce the reaction. Lidocaine is reported to exert a biphasic effect on the microvasculature, with contraction at low concentrations and relaxation at high concentrations.10

We compared S-TA 30- and 60-minute application times. There were no significant differences between the 30- and 60-minute application times for the pain outcomes. For FOI, 30 minutes, which followed 60 minutes per protocol, was better, possibly related to a period effect. Global impression of level of comfort with injections was not significantly different between the two times, although there was a trend in favor of 60 minutes (P = .1). When asked to rate their preference, participants were equally likely to choose either application time. A shorter application time is desirable for convenience. We suggest that further study may focus on a 30-minute application time and possibly include an even shorter time, such as 20 minutes.

These results include all participants who completed the trial. There was an imbalance in the number of participants favoring GA (n = 25), with only four participants taking IFNβ. Subgroup analysis yielded similar results for the GA group, and subgroup analysis could not be performed for IFNβ users. Further study is needed to characterize the effectiveness of S-TA, particularly for IFNβ-related injection pain.

Tolerability issues in this study included one participant with mild injection-site dermatitis and one participant who had repeated bouts of lightheadedness and muscle spasm after application. We believe that the safety profile is acceptable for further study. Of special relevance to MS, S-TA contains iron, so the patch must be removed before magnetic resonance imaging.

The limitations of this study include the trial design. It was an uncontrolled, open-label trial vulnerable to a placebo effect. The outcomes were almost exclusively subjective in nature and, thus, prone to large placebo effects. Factors limiting the generalizability of the results include small participant numbers, female predominance, and imbalance of numbers favoring GA use over IFNβ use. Only participants taking subcutaneous drugs, not intramuscular drugs, were included. Period effects cannot be excluded, although there were few differences between the 30- and 60-minute application times.

This was a brief study, and it is unknown whether the benefits would have been sustained with longer use. Level of interest was lower at the end of the study than at the midpoint. The inconvenience of having to wait for S-TA to take effect may reduce long-term use. The cost of treatment could deter sustained use. The S-TA is commercially available through a manufacturer-sponsored mail-order pharmacy (with copay support), specialty pharmacies, and select retail pharmacies.

This intervention may be most useful at the initial stage of treatment, when patients are still adjusting to injection therapy. However, this study was limited to participants who were already established users of subcutaneous injectables.

In conclusion, this open-label pilot study explored the clinical utility of a topical adhesive containing anesthetic and heating components in managing subcutaneous medication injections used for MS. Significant reductions in pain on injection; pain at 12 hours; pain, tenderness, and LISR scale scores at 24 hours; and FOI were recorded. Pain reductions were similar with 60- and 30-minute application times, suggesting that the shorter application time may be adequate. Safety issues were one case of muscle spasm and lightheadedness and one case of dermatitis. Larger, randomized trials are needed to test this novel treatment of injection pain caused by subcutaneous MS drug injections.

PracticePoints

Synera topical adhesive is a peel-and-stick patch containing lidocaine, tetracaine, and a heating element to warm the skin. It is a potential treatment to improve tolerance of injectable MS medications.

This open-label study of 30 participants with MS found statistically significant reductions on scores of pain and fear of injection with Synera topical adhesive applied 30 to 60 minutes before MS drug injection.

There was one adverse event involving muscle spasm and lightheadedness that led to treatment discontinuation and one adverse event of mild application-site dermatitis that resolved while the participant continued and completed the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carey Gonzales and Sherry Alboucq for help during the study and in manuscript preparation.

References

Stewart TM, Zung VT. Injectable multiple sclerosis medications: a patient survey of factors associated with injection-site reactions. Int J MS Care. 2012; 14:46–53.

Treadway K, Cutter G, Salter A, et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol. 2009; 256:568–576.

Verdun di Cantogno E, Russel S, Snow T. Understanding and meeting injection device needs in multiple sclerosis: a survey of patient attitudes and practices. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011; 5:173–180.

Ross PR, Singer B, Kresa-Reahl K, Al-Sabbagh A, Bennett R, Divan V. Reduction of injection-site reactions with hydrocortisone, with witch hazel, or moisturizing lotion after subcutaneous interferon beta 1a treatment for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13:S7–S273.

Pardo G, Boutwell C, Conner J, Denney D, Oleen-Burkey M. Effect of oral antihistamine on local injection site reactions with self-administered glatiramer acetate. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010; 42:40–46.

Buhse M. Efficacy of EMLA cream to reduce fear and pain associated with interferon beta 1a injection in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006; 38:222–226.

Jolly H, Simpson K, Bishop B, et al. Impact of warm compresses on local injection-site reactions with self-administered glatiramer acetate. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008; 40:232–239.

Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical rating scale. Pain. 2001; 94:149–158.

Farrar JT, Berlin JA, Strom BL. Clinically important changes in acute pain outcome measures: a validation study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003; 25:403–411.

Gherardini G, Samuelson U, Jembeck J, et al. Comparison of vascular effects of ropivacaine and lidocaine on isolated rings of human arteries. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1995; 39:765–768.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This study was funded by an independent medical grant from ZARS Pharma Inc and Galen US Inc.