Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Value, Challenges, and Satisfaction of Certification for Multiple Sclerosis Specialists

Background: Specialist certification among interdisciplinary multiple sclerosis (MS) team members provides formal recognition of a specialized body of knowledge felt to be necessary to provide optimal care to individuals and families living with MS. Multiple sclerosis specialist certification (MS Certified Specialist, or MSCS) first became available in 2004 for MS interdisciplinary team members, but prior to the present study had not been evaluated for its perceived value, challenges, and satisfaction.

Methods: A sample consisting of 67 currently certified MS specialists and 20 lapsed-certification MS specialists completed the following instruments: Perceived Value of Certification Tool (PVCT), Perceived Challenges and Barriers to Certification Scale (PCBCS), Overall Satisfaction with Certification Scale, and a demographic data form.

Results: Satisfactory reliability was shown for the total scale and four factored subscales of the PVCT and for two of the three factored PCBCS subscales. Currently certified MS specialists perceived significantly greater value and satisfaction than lapsed-certification MS specialists in terms of employer and peer recognition, validation of MS knowledge, and empowering MS patients. Lapsed-certification MS specialists reported increased confidence and caring for MS patients using evidence-based practice. Both currently certified and lapsed-certification groups reported dissatisfaction with MSCS recognition and pay/salary rewards.

Conclusions: The results of this study can be used in efforts to encourage initial certification and recertification of interdisciplinary MS team members.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive neurologic disease that is most commonly diagnosed in individuals between the ages of 20 and 50 years.1 It is characterized by inflammatory demyelinating and neurodegenerative damage, resulting in significant axonal and neuronal loss in the central nervous system2 that leads to marked physical disability and multiple symptoms.3 The symptoms vary within and across individuals throughout the course of the illness and may include fatigue; walking difficulty; balance deficits; lack of coordination; tremor; bowel, bladder, or sexual dysfunction; cognitive impairment; sensory disturbances; muscle weakness; heat intolerance; spasticity; visual deficits; pain; and depression.1 3– 5

Because MS strikes during the peak years of career development and family life, and because it can affect so many different physical, social, and psychological functions, it demands the coordinated efforts of an interdisciplinary team of health-care professionals working collaboratively with the affected individual and his or her care partners.5 If left untreated, MS symptoms may precipitate or exacerbate other health problems, and adverse effects of treatments for certain symptoms may further compromise other aspects of the person's functioning.3 4 Thus, management of MS must be coordinated, regularly evaluated, and modified according to the patient's value system and future scientific advances in order to maximize independence, reduce complications, and limit deterioration resulting from the disease.6

The complexity of MS disease manifestations requires an interdisciplinary team of health-care professionals with current clinical experience and knowledge of MS pathology, symptoms, and treatment. The primary team consists of a physician, a nurse, a physical therapist, an occupational therapist, and a speech/language pathologist.5 Additionally, access to a psychologist, a neuropsychologist, a social worker, a dietitian, an orthotist, and a vocational rehabilitation specialist may be needed to enhance the MS patient's health and safety, functional independence, and quality of life.5 7 The Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) encourages its multidisciplinary team members to avail themselves of specialist certification in MS (MS Certified Specialist, or MSCS). The Handbook for MSCS Candidates 8 identifies the following purposes of MS specialist certification:

Formally recognizing knowledge across the multiple disciplines that is necessary for MS care delivery.

Establishing a level of knowledge required for MS certification.

Providing encouragement for continued personal and professional growth in the care of individuals with MS.

Providing a standard of knowledge requisite for certification, thereby assisting the employer, public, and members of the health professions in the assessment of health-care professionals involved in MS care.

The purposes of MS specialist certification are consistent with Herzberg's9 theory of employee satisfaction, which includes enhanced achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility, and advancement. According to Herzberg, satisfaction with one's job motivates a person to aspire to superior performance, effort, and self-actualization. However, dissatisfaction occurs when environmental conditions consisting of organizational policy and administration, interpersonal relations, and working conditions are negative. Perceived values associated with certification lead to employee satisfaction, and various challenges and barriers may lead to employee dissatisfaction.

MS specialist certification became available for nurses in 2002, and in 2004 it became available for physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech/language pathologists, recreational therapists, physician assistants, psychologists, social workers, physicians, and others. The value of MS specialist certification reported by the specialist nurses includes enhanced role change and job satisfaction related to increased autonomy, colleagueship, leadership roles, and primary-care nursing.10 11 Prior to the present study, evaluation of MS specialist certification for additional members of the MS interdisciplinary team had not yet been undertaken. Information regarding the perceived benefits of MS specialist certification and perceived barriers to recertification may be used by the CMSC staff to intervene according to the types of challenges and barriers experienced by MS interdisciplinary team members who failed to renew their MS specialist certification.

Study Objectives

The objectives of the present study were as follows: 1) determine the perceived value of and perceived challenges and barriers to specialist certification among members of the MS interdisciplinary team; 2) determine whether differences exist regarding perceived value of and challenges and barriers to specialist certification between currently certified MS specialists and those who allowed their MS specialist certification to lapse; and 3) determine whether the perceived value of specialist certification is associated with job satisfaction and whether the perceived challenges or barriers to certification lead to job dissatisfaction.

Methods

Sample

Following receipt of study approval from the Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects in Research, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, the sample of MS certified specialists was recruited by the CMSC staff. The sample consisted of 67 currently certified MS specialists and 20 MS team members with lapsed MS specialist certification. As of September 2, 2011, there were 98 MS specialists who were up for recertification as well as 266 currently certified MS specialists (K Costello, e-mail communication, September 2, 2011).

Instruments

Study instruments included self-report scales used to obtain the perceived value of MS specialist certification, perceived challenges and/or barriers to recertification for MS specialists, and a single overall satisfaction item, as well as a demographic form.

Perceived Value of Certification Tool (PVCT)

The PVCT, an 18-item scale developed with samples of nurses, was used to measure each study participant's perceived value of MS specialist certification.12 Responses to scale items use a Likert-type format consisting of five categories: Strongly Agree (5), Agree (4), Disagree (3), Strongly Disagree (2), and No Opinion (1). Scores for the total scale range from 1 to 90, with higher scores indicating higher values for specialist certification. The internal consistency reliability coefficient for the total scale was 0.93.

Perceived Challenges and Barriers to Certification Scale (PCBCS)

The PCBCS, an 11-item scale developed with samples of nurses,13 was used to measure perceived challenges and barriers to specialist certification. Responses to scale items use a Likert-type format consisting of five categories: Strongly Agree (5), Agree (4), Disagree (3), Strongly Disagree (2), and No Opinion (1). Scores for the total scale range from 1 to 55, with higher scores indicating greater challenges and barriers to seeking certification. No psychometric properties for the PCBCS were reported.

Overall Satisfaction with Specialist Certification Scale

This single-item scale was used to determine the study participant's overall satisfaction since becoming MS specialist certified. Likert-type responses ranged from Extremely Satisfied (6) to Extremely Dissatisfied (1). Single-item scale indicators provide valuable information about an individual's perception of the concept under study.14

Demographic Data Form

The demographic form requested information pertaining to the study participant's gender, age, ethnicity, type of work setting, and major job responsibility. Three open-ended statements were added to determine whether role change occurred since becoming MS specialist certified and what was most satisfying and dissatisfying related to MS specialist certification.

Procedure

Study participants were recruited by staff from the CMSC. The CMSC staff sent a consent/information letter together with a copy of each questionnaire (PVCT, PCBCS, Overall Satisfaction with Certification Scale, demographic form) and a self-addressed and stamped return envelope to MS certified specialist participants by postal mail. Study questionnaires were returned to the CMSC, which subsequently forwarded them to the principal investigator for data analysis.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and parametric statistical procedures. Descriptive statistical procedures were used to describe the variables and demographic characteristics, and to determine whether the requirements were met for using parametric tests. Exploratory principal component factor analysis was used to determine the factor structure of the PVCT and the PCBCS, since the scales had not previously been used with MS subjects. Internal consistency reliability of the PVCT and PCBCS total scales and factored subscales was determined by the Cronbach α procedure. The independent t test was used to determine whether differences existed between currently certified study participants and those who had allowed their certification to lapse with regard to a) perceived value of certification and b) perceived challenges and barriers to certification. The Pearson product moment correlation procedure was used to compare PVCT, PCBCS, and Overall Satisfaction scale values for currently certified and lapsed-certification MS specialists.

Analysis of the three open-ended statements followed the content analysis procedure recommended by Krippendorff.15 The procedure included recording the written responses in a computer file, distributing data into categories by commonalities, applying codes to the categories, and establishing interrater reliability. Written responses were entered into a computer file consisting of the respondent's identification number, MS specialty area, certification status, and response to each of the three open-ended statements. Numbered codes were assigned to the categories. Coding instructions for Role Change, Role Satisfaction, and Role Dissatisfaction were given to the raters to independently categorize responses to the three statements. Interrater agreement was 90.5% for Role Change, 85.5% for Role Satisfaction, and 94.0% for Role Dissatisfaction.

Written responses with a frequency of 10% or more for at least one of the MS certified specialist groups for Role Change, Role Satisfaction, and Role Dissatisfaction are reported. The level of statistical significance was set at ≤.05.

Results

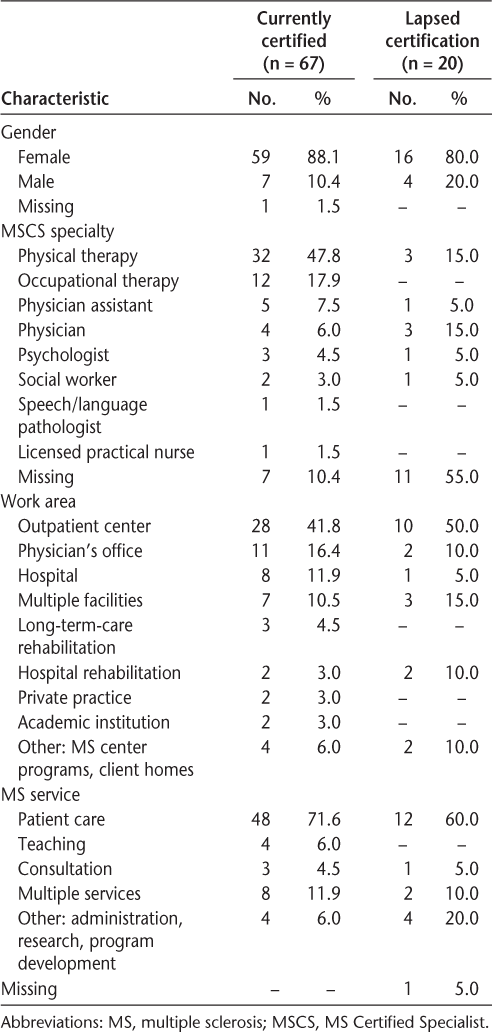

Demographic characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants were female, were white, had a specialty of physical therapy, worked in an outpatient center, and focused on patient care.

Sample characteristics of currently certified and lapsed-certification study participants

Exploratory principal component factor analysis of the PVCT resulted in four factors that explained 68.22% of the variance in the scale. Factor 1 (7 items) represented enhanced clinical confidence, satisfaction, challenge, autonomy, commitment, accountability, and personal accomplishment. Factor 2 (4 items) represented employer recognition, consumer confidence, marketability, and increased salary. Factor 3 (4 items) represented validation of specialized knowledge, clinical competence, attainment of practice standards, and professional growth. Factor 4 (3 items) represented enhanced professional credibility and recognition from peers and other health professionals. Cronbach α reliability coefficients ranged from 0.752 to 0.866 for the factored subscales and 0.911 for the total PVCT.

Exploratory principal component factor analysis of the PCBCS resulted in three factors that explained 58.38% of the variance in the scale. Factor 1 (3 items) represented failed certification examination, lack of interest in certification, and irrelevant to one's practice. Factor 2 (3 items) represented examination cost and lack of institutional support and reward. Factor 3 (5 items) represented a lack of access to preparatory courses, examination site, and continuing education, together with test-taking discomfort and cost to maintain one's credential. Cronbach α reliability coefficients ranged from 0.598 to 0.856 for the factored subscales and 0.691 for the total PCBCS.

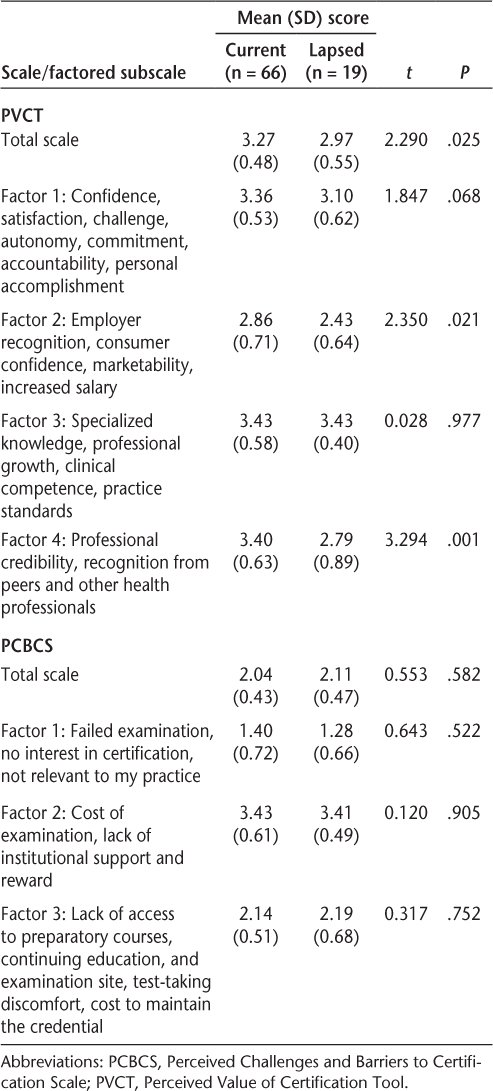

Comparison of the PVCT and PCBCS total scale and subscales by certification status is shown in Table 2. Currently certified MS specialists had significantly higher scores on the PVCT total scale and two of the factored subscales than lapsed-certification MS specialists. Specifically, currently certified MS specialists perceived greater employer recognition, consumer confidence, marketability, increased salary, professional credibility, and recognition from peers and other health professionals than did lapsed-certification MS specialists. No statistically significant difference was found between currently certified and lapsed-certification MS specialists for the PCBCS total scale or three subscales.

Comparison between currently certified and lapsed-certification participants on the PVCT and the PCBCS

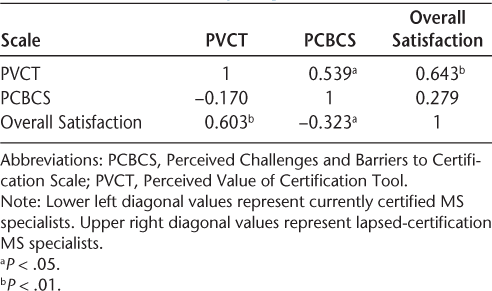

The correlation between Overall Satisfaction since becoming MS specialist certified and the PVCT was highly significant for both currently certified and lapsed-certification MS specialists (Table 3), indicating that both groups perceived considerable value in MS certification. In contrast, the correlation between Overall Satisfaction since becoming MS specialist certified and the PCBCS was moderately negative for currently certified MS specialists. Thus the value of MS specialist certification far outweighed the challenges and barriers to attaining such certification, but the correlation was not statistically significant for the lapsed-certification MS specialist group.

Pearson correlations between PVCT, PCBCS, and Overall Satisfaction scales by currently certified (N = 66) and lapsed-certification (N = 19) groups

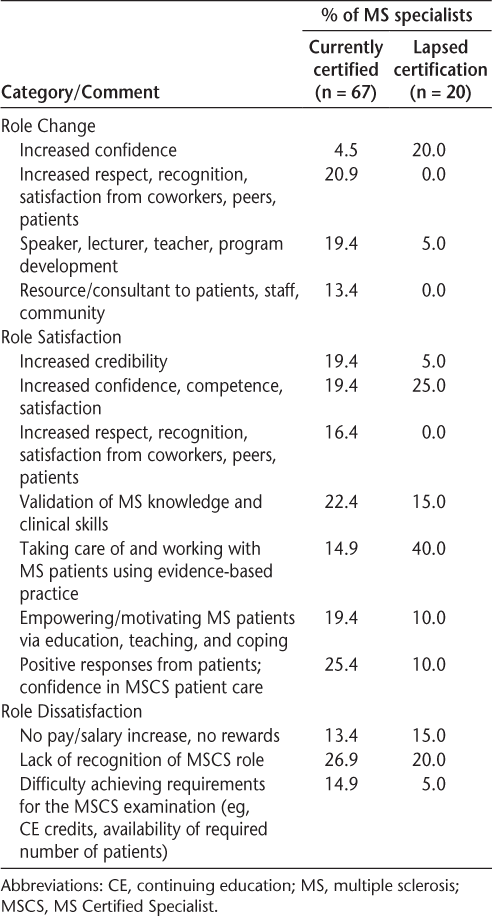

Responses to written statements pertaining to Role Change, Role Satisfaction, and Role Dissatisfaction differed between currently certified and lapsed-certification MS specialists. Role Change pertaining to increased respect and recognition; serving as speaker, lecturer, or teacher; or serving as a resource or consultant as a result of MS specialist certification was reported by 13.4% to 20.9% of currently certified MS specialists. However, 20% of those with lapsed MS specialist certification reported increased confidence, compared with 4.5% of currently certified MS specialists (Table 4). Increased respect, recognition, and satisfaction from coworkers, peers, and patients were identified in written responses as occurring in both Role Change and Role Satisfaction.

Percentages of currently certified and lapsed-certification MS specialists who reported Role Change, Role Satisfaction, and Role Dissatisfaction

Role Satisfaction pertaining to increased credibility, recognition, MS knowledge validation, empowering MS patients, and positive responses from patients ranged from 16.4% to 25.4% among currently certified MS specialists. Among lapsed-certification MS specialists, Role Satisfaction pertaining to increased confidence, MS knowledge validation, and care of MS patients using evidence-based practice ranged from 15% to 40% (Table 4).

Role Dissatisfaction was highest for a lack of MSCS role recognition for both currently certified (26.9%) and lapsed-certification (20%) MS specialists, followed by no pay/salary increase or rewards for currently certified (13.4%) and lapsed-certification (15%) MS specialists. Difficulty achieving requirements for the MSCS examination was reported by 14.9% of currently certified MS specialists (Table 4).

Discussion

The purposes of certification for MS interdisciplinary specialists, as outlined in the Handbook for MSCS Candidates, 8 are reflected in many of the PVCT scale items. Enhancement of specialized knowledge represented in PVCT, Factor 3, is consistent with the first two stated purposes of MS certification: to recognize and establish a level of knowledge across the multiple MS disciplines that is necessary for MS care delivery. Enhancement of professional growth and personal accomplishment—items represented in PVCT, Factor 3 and Factor 1, respectively—are reflected in the third stated purpose of MS certification: to provide encouragement for continued personal and professional growth in the care of individuals with MS. Recognition from employers and consumer confidence, items in Factor 2, are reflected in the fourth stated purpose of MS certification: to promote a standard of knowledge requisite for certification, thereby assisting the employer, public, and members of the health professions in the assessment of health-care professionals involved in MS care. Additional values of MS specialist certification contained in the PVCT but not directly identified in the stated purposes of MS specialist certification include enhanced credibility, accountability, clinical competence, marketability, and salary. However, the latter values were identified in written responses pertaining to Role Change and Role Satisfaction.

Statistically significant differences between currently certified and lapsed-certification study participants found for the total PVCT scale, but in particular for Factor 2 and Factor 4 items, suggest the important values that MS specialist certification provides interdisciplinary MS team members, their employers, individuals with MS, and the public. MS specialist certification enhances one's feelings of personal accomplishment, satisfaction, autonomy, commitment, and accountability to one's job, as shown in Factor 1 and in written responses pertaining to Role Satisfaction. Furthermore, MS specialist certification enhances one's recognition from his or her employer, consumer confidence, marketability, and salary, as shown in Factor 2. Written responses regarding recognition from one's coworkers and peers are also consistent with Factor 2.

Herzberg's9 theory of employee satisfaction, which includes enhanced achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility, and advancement, is evident in the PVCT factored subscales. Enhanced achievement is shown in Factor 3, pertaining to enhancement of specialized knowledge, professional growth, clinical competence, and practice standards. Enhanced recognition is shown in Factor 2, pertaining to employer recognition, and in Factor 4, regarding recognition from peers and other health professionals. Advancement is shown in Factor 2, pertaining to increased salary, and in Factor 3, pertaining to professional growth. Of interest is the finding that the single item measuring Overall Satisfaction with MS specialist certification demonstrates high correlations with the total PVCT score for both the currently certified and lapsed-certification study participants, suggesting that even those with lapsed certification perceive considerable value in MSCS certification.

Factor analysis of the PCBCS data in the current study yielded three factors, the first two of which demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency reliability. However, the third factor failed to reach a Cronbach α of 0.70, the suggested minimum reliability coefficient.16 17 Furthermore, the reliability for the total PCBCS scale was 0.691, slightly short of 0.70. No statistically significant differences between currently certified and lapsed-certification study participants were found for the total PCBCS scale and its subscales. The nonsignificant findings may be due to the somewhat low total scale reliability and the third factored subscale. They may also be due to the fact that mean scores for the PCBCS items differed little between the certified and lapsed-certification study participants. The latter point suggests that the MS certified specialists also experienced challenges and barriers to MS specialist certification that they were able to overcome. Of particular note are the moderately high mean scores for both currently certified and lapsed-certification study participants regarding the cost of the examination and lack of institutional support and reward for MS certification. Also noteworthy is the perceived lack of access to preparatory courses and continuing education, together with test-taking discomfort. The latter findings were also reported in written responses regarding Role Dissatisfaction by currently certified and lapsed-certification MS specialists.

Certification as an MS specialist not only achieves a practice standard aimed at promoting high-quality and consistent care to those living with MS, but also provides personal benefits to the health-care professional through enhanced role change and role satisfaction. The personal benefits of increased respect and recognition that accrued to MS certified specialists according to the current study are consistent with Herzberg's9 theory of employee satisfaction and with other reports in the literature pertaining to satisfaction among certified specialists.18– 22 Although increased marketability and pay or salary increases were perceived by few MS certified specialists in the current study, increased marketability and income have been reported for psychology certified specialists.19

The expanded role among MS specialists that included being a speaker, lecturer, or teacher or participating in program development occurred mostly among currently certified, compared with lapsed-certification, MS specialists. This has considerable value for MS patients but also for members of the interdisciplinary team who wish to become certified as MS specialists, as currently certified MS specialists can serve as role models. Few currently certified and no lapsed-certification MS specialists reported role expansion regarding research, organizational involvement, and increased responsibility. A study of MS certified nurse specialists (K Costello, e-mail communication, September 2, 2011) and sports specialists in physical therapy21 supported role expansion for some in the area of research. The opportunities for role expansion depend on many factors and conditions that may include one's available time and opportunity, as well as interest.

Role Satisfaction was highest for perceived credibility, confidence, recognition, knowledge validation, and patient care. Consistent with the current study findings, other studies have identified a number of factors that enhance satisfaction among certified nurses, including professional credibility, clinical competence, and recognition from employers, peers, and other health professionals, together with enhanced collaboration and empowerment.22 23 Certified physical therapists report a high level of satisfaction due to continued professional growth, development, and personal achievement.20

Consistent with the reported positive responses from MS patients regarding their care from MS certified specialists was the finding by Wade22 of positive responses from patients related to their satisfaction with certified specialty nurses. The American Board of Medical Specialties24 cited a number of studies that demonstrate improved patient outcomes in the presence of certified physicians. Also important is the improved collaboration and communication with members of the interdisciplinary team as a result of certification.22 25

Role dissatisfaction was greatest for lack of recognition of the MSCS role reported by currently certified (26.9%) and lapsed-certification MS specialists (20%). This finding is consistent with the study of job satisfaction among MS certified nurses (K Costello, e-mail communication, September 2, 2011). Dissatisfaction also occurred as a result of no pay/salary increases or rewards for currently certified (13.4%) and lapsed-certification (15%) MS specialists. A national study by the American Board of Nursing Specialties that examined nurses' perceptions, values, and behaviors related to certification reported that the most cited reasons for allowing certification to lapse were a lack of compensation and recognition for certification.13 Additional barriers to seeking certification or recertification among nurses,18 pharmacists,20 and physicians26 include the cost to maintain the credential. Importantly, there were few currently certified and lapsed-certification MS specialists who perceived dissatisfaction with patient care.

Limitations

The survey respondents in this study made up 25.2% and 20.4% of currently certified and lapsed-certification MS specialists, respectively, who were eligible to participate. Therefore, the results may not be representative of the total populations of currently certified and lapsed-certification MS specialists. Nevertheless, the findings identify important personal and professional values resulting from MSCS certification. Also, the identification of barriers, challenges, and dissatisfaction with MSCS certification may be useful to the CMSC staff in addressing areas of role dissatisfaction in order to promote currency of MS specialist certification.

Conclusion

The PVCT demonstrates satisfactory reliability for the total scale and factored subscales used with a sample of currently certified and lapsed-certification study participants. The PCBCS demonstrates satisfactory reliability for two of the three subscales. Possible revision of items in the PCBCS and further testing of the scale are suggested. The statistically significant differences found between the currently certified and lapsed-certification study participants on the total scale and two of the factored subscales of the PVCT can be used to encourage initial certification and recertification of interdisciplinary MS team members. Findings from further testing of the PCBCS, together with the open-ended responses pertaining to Role Change, Role Satisfaction, and Role Dissatisfaction, may provide additional information useful to this end.

PracticePoints

MS specialist certification provides formal recognition of a specialized body of knowledge felt necessary to provide optimal care to individuals and families living with MS.

MS certified specialists perceive greater consumer confidence, marketability, increased salary, and recognition from employers, peers, and other health professionals.

MS specialists who allowed their MS specialist certification to lapse perceive a lack of institutional support and rewards as well as a lack of access to preparatory courses, materials, examination site, and continuing education.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the following individuals who participated in establishing interrater agreement for the categories pertaining to Role Change, Role Satisfaction, and Role Dissatisfaction: Christine Smith, OTR/L, MSCS, Oradel Healthcare Center, Oradell, NJ; and Matthew H. Sutliff, PT, MSCS, Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research, The Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH. We also thank the MS specialists who participated in the study.

References

Sutliff MH , Miller D , Forwell S. Developing a functional capacity evaluation specific to multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2012;14(suppl 3):17–28.

Lublin FD , Yong VW , Harris C , Blumer R. Emerging strategies for neuroprotection and neuroregeneration in MS. Int J MS Care. 2011;13(suppl 2):5–29.

Crayton HJ , Rossman HS. Managing the symptoms of multiple sclerosis: a multimodal approach. Clin Ther. 2006;28:445–460.

Crayton H , Heyman RA , Rock A , Rossman HS. A multimodal approach to managing the symptoms of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63(suppl 5):S12–S18.

Kalb R, ed. Multiple Sclerosis: A Focus on Rehabilitation. 4th ed. New York, NY: Professional Resource Center, National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2010.

Burks J. Multiple sclerosis care: an integrated disease-management model. J Spinal Cord Med. 1998;21:113–116.

Stevenson VL , Playford ED. Rehabilitation and MS. Int MS J. 2007;14:85–92.

Multiple Sclerosis Specialist Certification Examination: Handbook for Candidates. New York, NY: Professional Testing Corp; 2013.

Herzberg F. Work and the Nature of Man. New York, NY: New American Library; 1973.

Gulick EE , Halper J , Costello K. Job satisfaction among multiple sclerosis certified nurses. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;39:244–255.

Gulick EE , Halper J , Namey M. Job satisfaction of multiple sclerosis certified nurses: qualitative study findings. Int J MS Care. 2008;10:69–75.

Sechrist KR , Berlin LE. Psychometric analysis of the Perceived Value of Certification Tool. J Prof Nurs. 2006;22:248–252.

Niebuhr B , Biel M. The value of specialty nursing certification. Nurs Outlook. 2007;55:176–181.

Youngblut JM , Casper GR. Single-item indicators in nursing research. Res Nurs Health. 1993;16:459–465.

Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004.

Nunnally JC , Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1994.

Polit DF. Data Analysis and Statistics for Nursing Research. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1996.

Byme M , Valentine W , Carter S. The value of certification—a research journey. AORN J. 2004;79:825–835.

Cox DR. Board certification in professional psychology: promoting competency and consumer protection. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24:493–505.

Ebiasah RP , Schneider PJ , Pedersen CA , Mirtallo JM. Evaluation of board certification in nutrition support pharmacy. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26:239–247.

Ellison J , Becker M , Nelson AJ. Attitudes of physical therapists who possess sports specialist certification. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;25:400–406.

Wade CH. Perceived effects of specialty nurse certification: a review of the literature. AORN J. 2009;89:183–192.

Gaberson KB , Schroeter K , Killen AR , Valentine WA. The perceived value of certification by certified perioperative nurses. Nurs Outlook. 2003;51:272–276.

American Board of Medical Specialties. Certification matters. http://www.certificationmatters.org/research-supports-benefits-of-board-certification. Accessed May 25, 2013.

Simmons JF , Skipper A , Lafferty LJ , Gregoire MB. A survey of perceived benefit and differences in therapy provided by credentialed and noncredentialed nutrition support dietitians. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27:282–286.

Iglehart JK , Baron RB. Ensuring physicians' competence—is maintenance of certification the answer? N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2543–2549.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Gulick has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Ms. Halper has served as a consultant to Acorda Therapeutics and is a speaker for non–continuing medical education programs for Acorda.