Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Treatment Satisfaction in Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Background: Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) are associated with inconvenient methods of administration, significant side effects, and low adherence rates. This study was undertaken to compare treatment satisfaction in MS patients treated with interferon beta-1a intramuscular (IFNβ-1a IM), interferon beta-1a subcutaneous (IFNβ-1a SC), glatiramer acetate (GA), and natalizumab (NTZ), and to examine the associations between treatment satisfaction ratings and adherence to therapy.

Methods: Two hundred twenty-six treated MS patients completed the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medicine. Multivariable models were used to compare treatment satisfaction across groups.

Results: There were no statistically significant differences in overall treatment satisfaction. The NTZ group reported greater satisfaction with the ability of the medication to treat or prevent MS than the IFNβ-1a IM group. The NTZ group also reported higher overall convenience scores than the IFNβ-1a IM group and greater satisfaction with ease of use of the medication than the interferon and GA groups. Patients in the IFNβ-1a IM group reported less satisfaction with ease of planning when to use the medication than those in the other groups. Convenience was associated with adherence in IFNβ-1a SC- and GA-treated patients, with lower convenience scores associated with lower adherence.

Conclusions: These results may be useful to MS patients and health-care providers facing decisions about DMT use.

Over the last 20 years, a number of immunomodulatory drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). They include interferon beta-1b (IFNβ-1b; Betaseron, Extavia), interferon beta-1a intramuscular (IFNβ-1a IM; Avonex), glatiramer acetate (GA; Copaxone), interferon beta-1a subcutaneous (IFNβ-1a SC; Rebif), mitoxantrone (Novantrone), and natalizumab (NTZ; Tysabri). More recently, three oral medications have been approved for MS: fingolimod (Gilenya), teriflunomide (Aubagio), and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera). In clinical trials, these drugs were found to be able to affect the disease process by reducing the frequency of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) relapses.1– 8 Their effects on measures of disease progression have been less consistent.1– 3 9 10

Despite the benefits of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for MS, several problems are associated with their use, including inconvenient methods and schedules of administration, long periods of therapy, and significant side effects.11 12 In addition, DMT use is complicated by the unpredictability of the MS disease course and the fact that disease-modifying drugs do not provide direct relief of ongoing MS-related symptoms. The many problems associated with DMT use may affect an individual's adherence to therapy. In fact, the proportion of nonadherent patients on DMTs has been reported to be as high as 45%.13

Devonshire et al.14 examined reasons for discontinuation of therapy in a multicenter study of adherence to IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, IFNβ-1b, and GA. Adherence was associated with female gender, ease of administration, satisfaction with therapy, treatment at a dedicated MS center, and family support. Rio et al.15 examined the factors influencing discontinuation of DMT in patients treated with IFNβs and GA. Lack of efficacy and treatment side effects were the two most common reasons cited for the discontinuation of therapy.

In addition to reports on adherence and tolerability, there are several studies that directly assessed treatment satisfaction in MS. In a study comparing IFNβs and GA, participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with therapy from 1 (“very satisfied”) to 6 (“very unsatisfied”). Participants were most satisfied with GA, followed by IFNβ-1b, and least satisfied with IFNβ-1a IM and IFNβ-1a SC, although the differences between groups were not statistically significant.12 Turner et al.16 examined DMT satisfaction in patients treated with IFNβ-1b, IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, and GA at 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months. Participants were asked how satisfied they were with their DMT, with responses ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“extremely”). The mean satisfaction ratings were 4.12 ± 1.09 at 2 months, 3.85 ± 1.25 at 4 months, and 4.19 ± 1.17 at 6 months. There were no differences in satisfaction ratings across DMT types. Perceived benefits of medication use predicted satisfaction at all three time points.

In this study, our first goal was to compare treatment satisfaction in people with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) treated with IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, GA, and NTZ using a 14-item treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Our second goal was to examine the associations between treatment satisfaction measures and adherence to therapy.

Methods

Participants and Measures

Participants were selected from the Comprehensive Longitudinal Investigation of Multiple Sclerosis at the Brigham and Women's Hospital, Partners Multiple Sclerosis Center (CLIMB), an ongoing prospective observational cohort study that began enrolling participants in 2000.17 This study is approved by the Partners Human Research Committee. Inclusion criteria for CLIMB are age of at least 18 years and a clinically isolated syndrome or diagnosis of RRMS according to the revised McDonald criteria.18 Participants have clinical visits every 6 months that include complete neurologic examinations and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) ratings.19 A subset of CLIMB participants complete a battery of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures annually. We analyzed the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) and a treatment adherence question. The TSQM consists of 14 items scaled on a 5- to 7-point bipolar scale. Items are combined into four summary scores using the published scoring algorithm: effectiveness, side effects, convenience, and overall satisfaction. For all questions and summary scores, higher scores imply higher levels of satisfaction. We calculated the Cronbach α for the four TSQM scales and found acceptable values for the Effectiveness (0.93), Side Effects (0.79), Convenience (0.86), and Overall Satisfaction (0.87) summary scales. These values are in keeping with those reported in the original TSQM validation studies (0.86–0.90).20

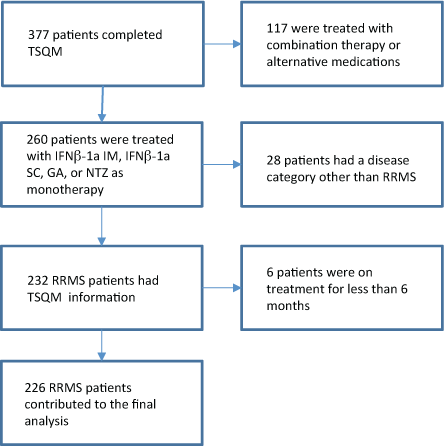

The treatment adherence question asks participants whether or not they have missed any doses of their DMT in the past 4 weeks. CLIMB participants with RRMS treated with IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, GA, or NTZ for at least 6 months who completed the TSQM (n = 226) were included in this analysis. A flow diagram summarizing how the overall study population was reduced to the final cohort is provided in Figure 1.

Flow diagram summarizing how the overall study population was reduced to the final cohort

Statistical Analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the treatment groups at the time the questionnaire was administered were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables, the Kruskal-Wallis test for EDSS, and the Fisher exact test for dichotomous variables. If significant group differences were found, pairwise group comparisons were completed with Holm's correction for multiple comparisons. For the comparison of treatment satisfaction across groups, both the summary scores and individual items for effectiveness, side effects, convenience, and overall satisfaction were analyzed. Given the differences between groups in terms of demographic and clinical features, we utilized multivariable linear regression to adjust for potential confounders (EDSS score, age, gender, and time on treatment). For the comparison of the presence of side effects, multivariable logistic regression was used, controlling for the same confounding factors. If the four-group comparison was statistically significant, pairwise comparisons were completed to estimate differences between each of the individual treatments, and adjusted group mean differences and associated 95% confidence intervals were reported. Both unadjusted P values and P values adjusted for multiple comparisons using Holm's correction for the group comparisons were reported.

The associations between the four treatment satisfaction summary scores and adherence were estimated using simple and multivariable logistic regression models. In this study, adherence was assessed over the previous 4 weeks. Since the number of doses over the course of the month varies by treatment and the likelihood of missing a single dose is treatment-dependent, we completed separate analyses for each of the treatment groups.

Results

Demographics

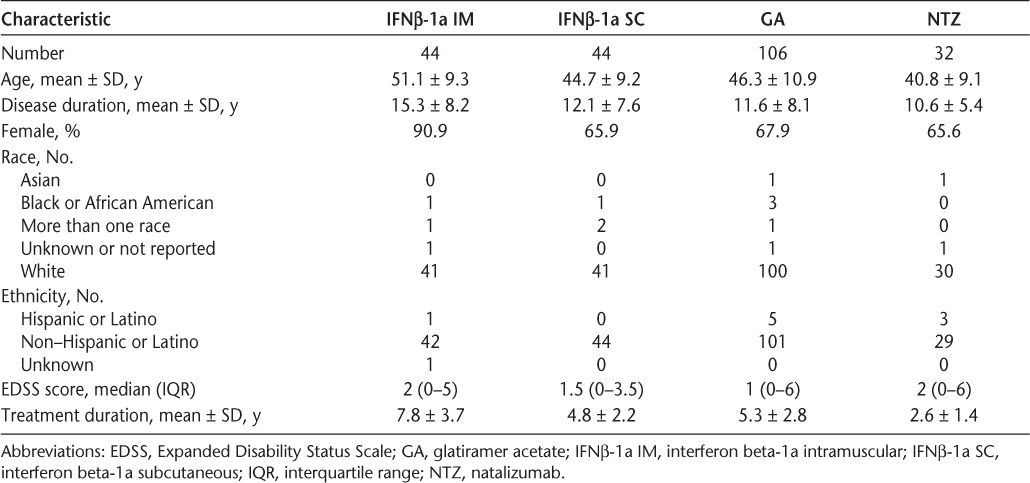

The demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants by treatment group are shown in Table 1. Glatiramer acetate was the most commonly used treatment, followed by IFNβ-1a SC and IFNβ-1a IM. The treatment groups were significantly different in terms of age, disease duration, gender, EDSS score, and treatment duration (P < .05 for four-group comparison for each outcome). In particular, participants treated with IFNβ-1a IM were significantly older, were significantly more likely to be female, and had a significantly longer time on treatment than those in any of the other treatment groups (P < .05 for all pairwise comparisons). In addition, NTZ-treated participants had a significantly shorter time on treatment (2.6 ± 1.4 years) than those in any of the other treatment groups (P < .05), and were significantly younger than GA-treated participants. Participants treated with IFNβ-1a IM had the longest disease duration (15.3 ± 8.2 years), but the only statistically significant difference in disease duration was between GA-treated or NTZ-treated participants and IFNβ-1a IM-treated participants.

Demographic characteristics of study participants

Effectiveness

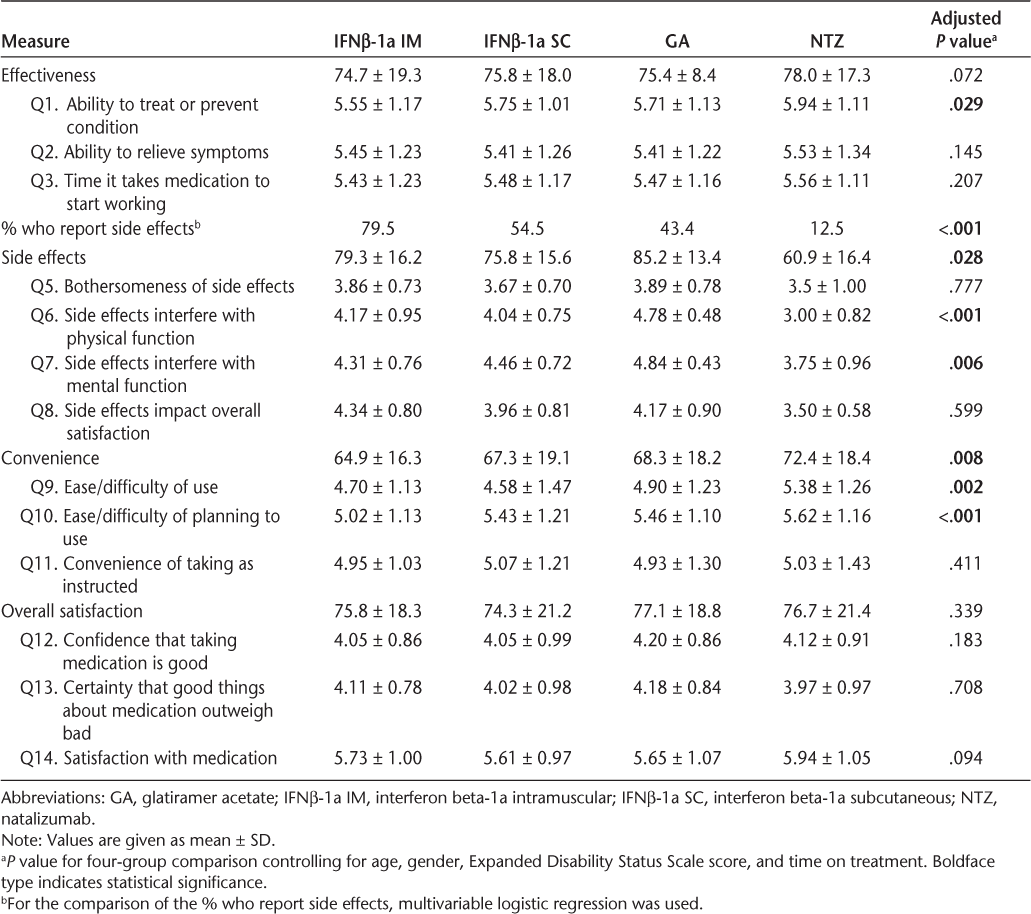

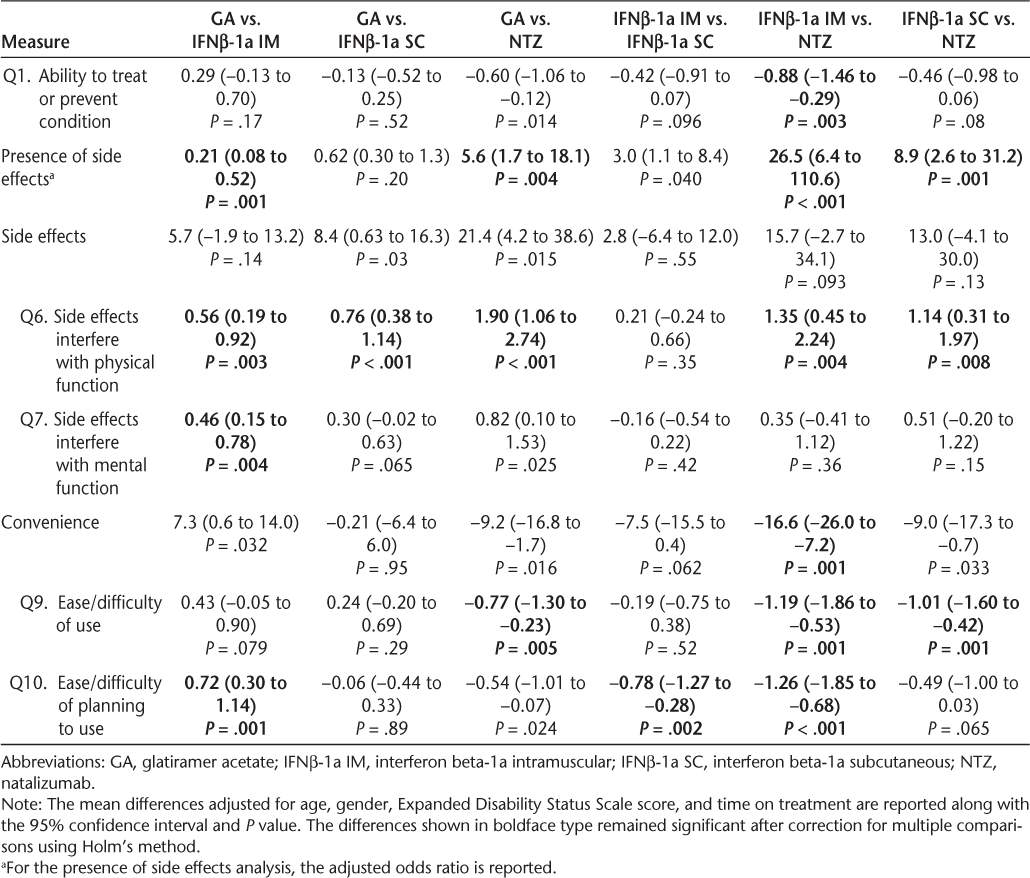

The results of multivariable regression are presented in Table 2. Pairwise comparisons are provided in Table 3. There was no statistically significant group difference on the effectiveness summary score. When the individual effectiveness items were considered, a significant difference was observed for the treatment's ability to “treat or prevent your condition.” In particular, the comparisons between GA vs. NTZ and IFNβ-1a IM vs. NTZ showed a significant difference between the groups, and the difference between IFNβ-1a IM and NTZ remained after correction for multiple comparisons. No statistically significant group differences were observed for the remaining effectiveness items, including the ability to relieve symptoms and the time it takes the medication to start working.

Treatment satisfaction measures

Adjusted group differences and 95% confidence intervals

Side Effects

The proportion of participants reporting side effects was significantly different across the treatment groups (P < .001). Significantly fewer participants treated with NTZ reported side effects than those in the other treatment groups, and significantly more participants treated with IFNβ-1a IM reported side effects than those in the GA and NTZ treatment groups (P < .05 for each comparison after correction for multiple comparisons). Among the participants who reported side effects, there was a statistically significant difference (P = .03) on the side effects summary score, with NTZ-treated participants reporting the lowest levels of satisfaction. Although the differences between GA- and IFNβ-1a SC-treated participants and GA- and NTZ-treated participants were significant in unadjusted analyses, neither result remained significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. When the individual side effect items were considered, significant treatment effects were observed for the impact of side effects on physical health (P < .001) and mental health (P = .006). For the physical health question, all group comparisons were statistically significant even after correction for multiple comparisons except the IFNβ-1a IM vs. IFNβ-1a SC comparison, and participants treated with GA reported the highest level of satisfaction with the impact of side effects on physical health. Participants treated with NTZ or IFNβ-1a IM reported less satisfaction with the impact of side effects on mental health than those treated with GA, and the comparison of GA vs. IFNβ-1a IM remained significant after correction for multiple comparisons.

Convenience

A statistically significant difference across the treatment groups was observed on the convenience summary score (P = .008). In particular, participants treated with NTZ reported the highest convenience scores, and NTZ was found to be significantly more convenient than IFNβ-1a IM after correction for multiple comparisons. Other group differences showed a trend toward statistical significance, but these were not significant after correction for multiple comparisons (GA vs. NTZ, GA vs. IFNβ-1a IM, and IFNβ-1a SC vs. NTZ). When the individual convenience items were investigated, participants in the NTZ group reported significantly higher scores than those in the other treatment groups for ease or difficulty of use (P < .05 for each comparison after correction for multiple comparisons). In addition, participants treated with IFNβ-1a IM reported significantly lower scores for convenience related to the ease or difficulty of planning to use the medication compared with planning to use the other treatments (P < .05 for each comparison).

Overall Satisfaction

In adjusted analyses, no statistically significant differences were observed between the four treatment groups in terms of the overall satisfaction summary score or the individual satisfaction items. Confidence that taking the medication is good, certainty that the good things about the medication outweigh the bad things, and overall satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the medication were not significantly different across treatment groups.

Effect of Treatment Satisfaction on Adherence

The proportion of participants who reported failing to take all of their prescribed doses of medication over the previous month was significantly different across treatments (P < .0001). Treatments with a greater number of doses per month had lower rates of complete adherence. The rate of complete adherence was 52.8% for GA, 77.3% for IFNβ-1a SC, 93.2% for IFNβ-1a IM, and 96.9% for NTZ. For NTZ and IFNβ-1a IM, none of the treatment satisfaction measures were associated with nonadherence, but this analysis was limited by the small number of participants who reported having missed doses. For IFNβ-1a SC, the side effects summary score (in the subset of participants who reported side effects), convenience summary score, and overall satisfaction summary score were all associated with decreased adherence (Supplementary Table 1). In a multivariate analysis including presence of side effects, convenience, overall satisfaction, and effectiveness, convenience was independently associated with adherence, while the other measures were not. For GA, the presence of side effects and the convenience summary scores were significantly associated with adherence in univariate models, and convenience was associated with adherence in the multivariate model (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

The introduction of DMTs has led to reductions in disease activity1–5 and improvements in quality of life21 22 for people with MS. We compared treatment satisfaction ratings in RRMS patients treated with IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, GA, and NTZ and found no differences in overall treatment satisfaction across therapies. Participants reported that they were confident that taking the medication was a good thing for them and that they were certain that the good things about the medication outweighed the bad things. There were differences, however, in the perceived effectiveness, side effects, and convenience associated with each treatment.

Participants reported that they were satisfied with the effectiveness of DMT in MS. Those treated with NTZ had the highest satisfaction with effectiveness ratings, and they were significantly more satisfied with the ability of the medication to treat or prevent MS than were those treated with IFNβ-1a IM. There were no significant differences across DMTs in terms of satisfaction with the ability of the DMT to relieve symptoms or with the time it takes the DMT to start working. In the AFFIRM trial, NTZ was shown to confer a 68% reduction in relapse rate and an 83% reduction in new and enlarging lesions compared with placebo.4 These reductions are larger than those observed in the pivotal trials for IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, and GA.2 3 9 Although there has been no head-to-head clinical trial demonstrating the increased efficacy of NTZ over the other DMTs, it is likely that some patients who begin NTZ assume the increased risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy,23 a rare but serious adverse effect of NTZ, for a presumed, if not clearly demonstrated, increase in efficacy.

Side effects were reported in 80% of participants treated with IFNβ-1a IM, 55% of those treated with IFNβ-1a SC, 43% of those treated with GA, and 13% of those treated with NTZ. A significantly higher proportion of participants treated with IFNβ-1a IM reported side effects than of those treated with GA and NTZ. Among participants who reported side effects, those treated with IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, and NTZ reported that the side effects interfered more with physical health and ability to function than those treated with GA. Participants treated with IFNβ-1a IM reported that the side effects interfered more with mental function, including the ability to think clearly and stay awake, than those treated with GA. There were no differences across treatment groups in terms of how bothersome the side effects were perceived to be, and in general, participants reported that they found the side effects to be somewhat or a little bothersome. Given that GA and IFNβs have similar efficacy profiles, the fact that GA-related side effects interfered less with physical and mental functioning might be useful in treatment decision making. A patient who is considering DMT might benefit not only from a discussion of efficacy and potential side effects, but also from information on the expected impact of those side effects on usual activities.

Disease-modifying therapies for RRMS include daily (GA), three times per week (IFNβ-1a SC), weekly (IFNβ-1a IM), and monthly (NTZ) treatment regimens. Routes of administration are subcutaneous (GA, IFNβ-1a SC), intramuscular (IFNβ-1a IM), and intravenous (NTZ). Natalizumab-treated participants reported greater satisfaction with overall convenience than IFNβ-1a IM-treated participants. More specifically, NTZ was described as more convenient in terms of its ease or difficulty of use than IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, and GA. It is interesting that although NTZ is the only DMT to require a monthly visit to an infusion center, it is perceived as more convenient than the other treatment regimens requiring self-injection. It is not clear how patients will rate the convenience of daily oral medications compared with monthly infusions.

In terms of ease or difficulty of planning when to use the medication, IFNβ-1a IM was rated significantly less convenient than IFNβ-1a SC, GA, and NTZ. We were surprised to find that the weekly DMT was considered less convenient to plan to use than daily or three times per week DMT, suggesting that daily or three times per week routines are easier to establish than weekly routines. The flu-like symptoms associated with IFNβ-1a IM may also contribute to the difficulties associated with planning when to use the medication. Working patients, for example, may choose to inject IFNβ-1a IM on Friday evenings to avoid experiencing flu-like symptoms during the work week. If a patient has a family event scheduled over the weekend, he or she may have to rethink when to use the medication.

A major consequence of patients' satisfaction or dissatisfaction with treatment is future DMT use.20 As expected, DMTs with a greater number of prescribed doses per month had lower rates of complete adherence. Adherence rates were 97% for NTZ, 93% for IFNβ-1a IM, 77% for IFNβ-1a SC, and 53% for GA. We found that convenience was associated with adherence in participants taking IFNβ-1a SC and GA, but not NTZ or IFNβ-1a IM. Lower convenience scores were associated with lower adherence rates. Other variables that have been shown to influence adherence include EDSS score, depression, informational deficits, and social support.11 It may be possible to improve treatment adherence using psychosocial interventions that incorporate informational, behavioral, and motivational components.

Dissatisfaction with injectable DMTs may lead some patients with MS to switch to oral therapies. There are no data currently available to indicate what proportion of patients treated with injectable medications has switched, but it is likely to be a growing trend. Despite the appeal of oral therapies, we believe that injectable DMTs and natalizumab will continue to play a role in the treatment of MS patients. These drugs have been shown to have significant disease-modifying effects, manageable side effects, and good safety profiles.24 25 Our findings suggest that, overall, patients are satisfied with injectable DMTs. This information may be especially helpful to newly diagnosed patients faced with deciding between new oral medications and injectable treatments that have been around for more than 10 years.

There are several limitations associated with this study. First, the sample size was relatively small, which could limit the generalizability of the results. Second, the sample did not include patients treated with IFNβ-1b, as there are very few patients at our center who are treated with IFNβ-1b. Third, there are few data on the psychometric qualities of the TSQM, and it has not been validated for use with MS patients. Fourth, the study did not include any independent measures of adherence. We relied instead on subject self-report, which may not be accurate. Fifth, we did not consider previous DMT use in the analysis. It is possible that satisfaction with a current DMT is influenced by experience with previous therapies. Finally, because the CLIMB study is not a patient registry but a volunteer cohort recruited from a tertiary referral center, we cannot be sure that CLIMB participants effectively represent the general populations of MS patients with RRMS, but this should not explain differences across treatment groups.

In summary, there were no differences in overall treatment satisfaction in RRMS patients treated with IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, GA, and NTZ, but there were differences across groups in terms of satisfaction with effectiveness, side effects, and convenience. Natalizumab-treated participants reported greater satisfaction with the ability of the medication to treat or prevent their condition than IFNβ-1a IM-treated participants. Participants in the GA group were more satisfied with the impact of side effects on physical function than those in the IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, and NTZ groups. Participants in the GA group were also more satisfied with the impact of side effects on mental function than those in the IFNβ-1a IM group. In terms of convenience, the NTZ group reported significantly higher overall convenience scores than the IFNβ-1a IM group and greater satisfaction with the ease of use of the medication than the IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, and GA groups. Participants treated with IFNβ-1a IM reported less satisfaction with ease of planning when to use the medication each time than those treated with IFNβ-1a SC, GA, or NTZ. These data may be useful to patients and health-care providers faced with decisions about DMT use.

PracticePoints

This study found no differences in overall treatment satisfaction among MS patients treated with interferon beta-1a intramuscular (IFNβ-1a IM), interferon beta-1a subcutaneous (IFNβ-1a SC), glatiramer acetate (GA), and natalizumab (NTZ).

Patients treated with NTZ reported greater satisfaction with the ability of the medication to treat or prevent MS than those treated with IFNβ-1a IM.

Glatiramer acetate–related side effects were reported to interfere less with physical functioning than those related to IFNβ-1a IM, IFNβ-1a SC, and NTZ; GA-related side effects were also reported to interfere less with mental functioning than those related to IFNβ-1a IM.

Natalizumab was described as most convenient in terms of ease or difficulty of use, and IFNβ-1a IM was rated least convenient in terms of planning when to use the medication.

References

The IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: I. Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1993;43:655–661.

PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and Disability by Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneously in Multiple Sclerosis) Study Group. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998;352:1498–1504.

Johnson KP , Brooks BR , Cohen JA, etal.; The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1995;45:1268–1276.

Polman CH , O'Connor PW , Havrdova E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:899–910.

Kappos L , Radue EW , O'Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:387–401.

O'Connor P , Wolinsky JS , Confavreux C, et al. Randomized trial of oral teriflunomide for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1293–1303.

Fox RJ , Miller DH , Phillips JT, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1087–1097.

Gold R , Kappos L , Arnold DL, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1098–1107.

Jacobs LD , Cookfair DL , Rudick RA, et al.; The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG). Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:285–294.

Johnson KP , Brooks BR , Cohen JA, et al.; Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Extended use of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) is well tolerated and maintains its clinical effect on multiple sclerosis relapse rate and degree of disability. Neurology. 1998;50:701–708.

Klauer T , Zettl UK. Compliance, adherence, and the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2008;255(suppl 6):87–92.

Twork S , Nippert I , Scherer P , Haas J , Pohlau D , Kugler J. Immunomodulating drugs in multiple sclerosis: compliance, satisfaction and adverse effects evaluation in a German multiple sclerosis population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:1209–1215.

Portaccio E , Zipoli V , Siracusa G , Sorbi S , Amato MP. Long-term adherence to interferon beta therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2008;59:131–135.

Devonshire V , Lapierre Y , Macdonell R, et al. The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:69–77.

Rio J , Porcel J , Tellez N, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:306–309.

Turner AP , Kivlahan DR , Sloan AP , Haselkorn JK. Predicting ongoing adherence to disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: utility of the health beliefs model. Mult Scler. 2007;13:1146–1152.

Gauthier SA , Glanz BI , Mandel M , Weiner HL. A model for the comprehensive investigation of a chronic autoimmune disease: the multiple sclerosis CLIMB study. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:532–536.

Polman CH , Reingold SC , Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria.” Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840–846.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452.

Atkinson MJ , Sinha A , Hass SL, et al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:12.

Jongen PJ , Sindic C , Carton H , Zwanikken C , Lemmens W , Borm G. Improvement of health-related quality of life in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients after 2 years of treatment with intramuscular interferon-beta-1a. J Neurol. 2010;257:584–589.

Jongen PJ , Lehnick D , Sanders E, et al. Health-related quality of life in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients during treatment with glatiramer acetate: a prospective, observational, international, multi-centre study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:133.

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK , Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:369–374.

Hutchinson M. In the coming year we should abandon interferons and glatiramer acetate as first line therapy for MS: commentary. Mult Scler. 2012;19:29–30.

Hillert J. In the coming year we should abandon interferons and glatiramer acetate as first line therapy for MS: no. Mult Scler. 2012;19:26–28.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Glanz has received research support from Merck Serono S.A. Mr. Musallam has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Rintell has received research support from Merck Serono S.A. and consulting fees from Biogen Idec and Novartis. Dr. Chitnis has received research support from Merck Serono S.A. and Novartis and consulting fees from Biogen Idec, Teva Pharmaceutical, and Novartis. Dr. Weiner has received research support from Merck Serono S.A. and consulting fees from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono S.A., and Teva Pharmaceutical. Dr. Healy has received research support from Merck Serono S.A. and Novartis.

Funding/Support: This work was supported in part by the Nancy Davis Foundation and Merck Serono S.A.