Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

The Evolving Role of the Multiple Sclerosis Nurse

A greater understanding of the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS) and the need for treatments with increased efficacy, safety, and tolerability have led to the ongoing development of new treatments. The evolution of treatments for MS is expected to have a dramatic impact on the entire health-care team, especially MS nurses, who build strong collaborative partnerships with their patients. MS nurses help patients better understand their disease and treatment options, facilitate the initiation and management of treatment, and encourage adherence. With new oral therapies entering the market, the potential for increased efficacy, tolerability, adherence, and convenience for patients is evident. However, the resulting change in the treatment paradigm means that the skill set required of an MS nurse will inevitably expand. There will be a growing need for professional training and development to ensure that nurses are familiar with the wider range of treatments and their specific modes of action, dosing schedules, and benefit/risk profiles. In addition, the MS nurse's role will expand to include management of the complex monitoring needs specific to each therapy. This article explores how the role of the MS nurse is evolving with the development of new MS therapies, including novel oral therapies.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic and progressive immune-mediated disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) affecting about 2.5 million people worldwide.1 Over the past 2 decades, our understanding of the immunopathophysiology of MS has greatly increased, which has led to the emergence of many new treatments with novel mechanisms of action. The introduction of disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) for the treatment of MS in the 1990s and the subsequent approval of a number of these drugs confirmed that, while MS is not yet curable, it is treatable.2 Further changes in the treatment landscape, including the development and approval of oral formulations and therapies, are under way, and these drugs are expected to become widely available in the near future.

Because of the complex nature of MS and the wide range of symptoms and problems faced by patients with the disease, a comprehensive care team is required to provide the support needed for effective disease management. Pivotal members of this team include the nursing professionals who not only are involved in the diagnosis, treatment, and management of MS but also provide patients and their families with the education, support, and counseling that they need. The role of the MS nurse is dynamic and has evolved dramatically since the approval and introduction of injectable DMD therapies, as well as in response to the specific challenges of MS and its management; this role will continue to change as further advances in treatment are made.

Evolution of MS Therapy and the Role of Nurses in MS

The treatment paradigm for MS has seen many developments over the past few decades, in terms of both treatment selection and timing of treatment initiation. Historically, patients with MS were prescribed therapy only once their disease had progressed to relatively advanced stages and when disability was already present; however, it has since been observed that processes leading to irreversible damage in MS can start during the early stages of the disease. Several clinical studies showing the benefits of early treatment in delaying the conversion of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) to MS have supported these observations. Consequently, early treatment is now recommended in order to achieve the optimal therapeutic effect.3–8

As our understanding of the pathophysiology of MS has advanced, so too have the available treatment options, evolving from palliative care to specific treatments targeting the cause of the disease. Type I interferons were first used in the 1970s based on the theory that their antiviral activity may reduce the environmental triggers of MS. The subsequent development and approval of specific beta-interferons, along with the development of glatiramer acetate, did not come until the early 1990s; these agents are now used as first-line therapies for MS. More recently, two additional therapies have been developed: mitoxantrone—a chemo-therapeutic agent—and natalizumab, a monoclonal antibody.9 Mitoxantrone is indicated for use in patients with secondary (chronic) progressive, progressive relapsing, or worsening relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).10 Natalizumab is generally recommended for patients who have had an inadequate response to, or are unable to tolerate, first-line MS therapies and may be used as a first-line treatment in patients with more disabling relapses.11 In 2010, the first marketing approvals were granted for the use of oral treatments for MS. Until this point, all approved DMD therapies were parenterally administered. The availability of the DMD therapies varies greatly across regions, and not all therapies are available in all countries.

With the advances in treatment options and the increasing demands placed on health-care systems, the need for MS nursing specialization has grown. An MS nurse can be defined broadly as a registered nurse with specialized knowledge, skills, and experience in the care of patients with MS and their families.12 However, the exact criteria and qualifications required to be an MS nurse vary greatly across different clinic settings and countries, and the spectrum of educational and practical preparations can range from diplomas to doctorate degrees. In addition, the scope of nursing practice can vary from direct patient care to MS nurse-run clinics and from roles in the community or hospital to those in academia or the pharmaceutical industry. The MS Nursing Certification (MSCN) was established by the Multiple Sclerosis International Certification Board and the International Organization of Multiple Sclerosis Nurses (IOMSN) in recognition of the international relevance and standard of care in the domains of MS nursing— clinical practice, advocacy, education, and research.13 This certification is meant to acknowledge the expertise of a registered nurse (or international equivalent) with a recommended 2 years' experience working in the four domains of MS nursing.

The evolution of MS therapy has had a dramatic impact on the role of the MS nurse, as nurses are becoming increasingly involved in the diagnosis, management, and support of patients with MS. The introduction of new MS therapies has led to an increased need for nurses to be involved in counseling patients on treatment decisions and providing education on treatment initiation, as well as monitoring and managing any side effects, assessing treatment outcomes, and encouraging patients to adhere to their treatment regimens. Managing patient expectations of therapy is also important, especially when patients experience relapse or tolerability concerns and require reassurance and support. The increased number of available treatments, with varying dosing regimens and methods of administration, has required MS nurses to expand and adapt their knowledge and skill sets to ensure that they can serve as key sources of accurate information for their patients.

As MS is commonly first diagnosed in young adults, disease progression often occurs in the prime of life and can have a negative impact on long-term career and job prospects, relationships, and family planning. This can lead to financial hardships, strained family relations, and feelings of social isolation, all of which require effective coping strategies. As a key figure in the care of patients with MS, the specialist nurse now plays a growing role in coordinating patient support and care and encouraging adherence to therapy.14 The complexity of MS care has given rise to the comprehensive care team approach, with the team including nurses, physicians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, psychologists, and dietitians. It is important that MS nurses recognize the support and expertise that other members of the team can provide, especially given increasing nursing workloads. The comprehensive care team is patient-centric and focuses on working with the patient to develop a tailored disease-management plan. While each member of the care team makes an important contribution to the management plan and goals, it is often the MS nurse who assumes the role of coordinator to bring together the services of all the members of the team.12

The Present-Day MS Nurse—A Key Role in Adherence

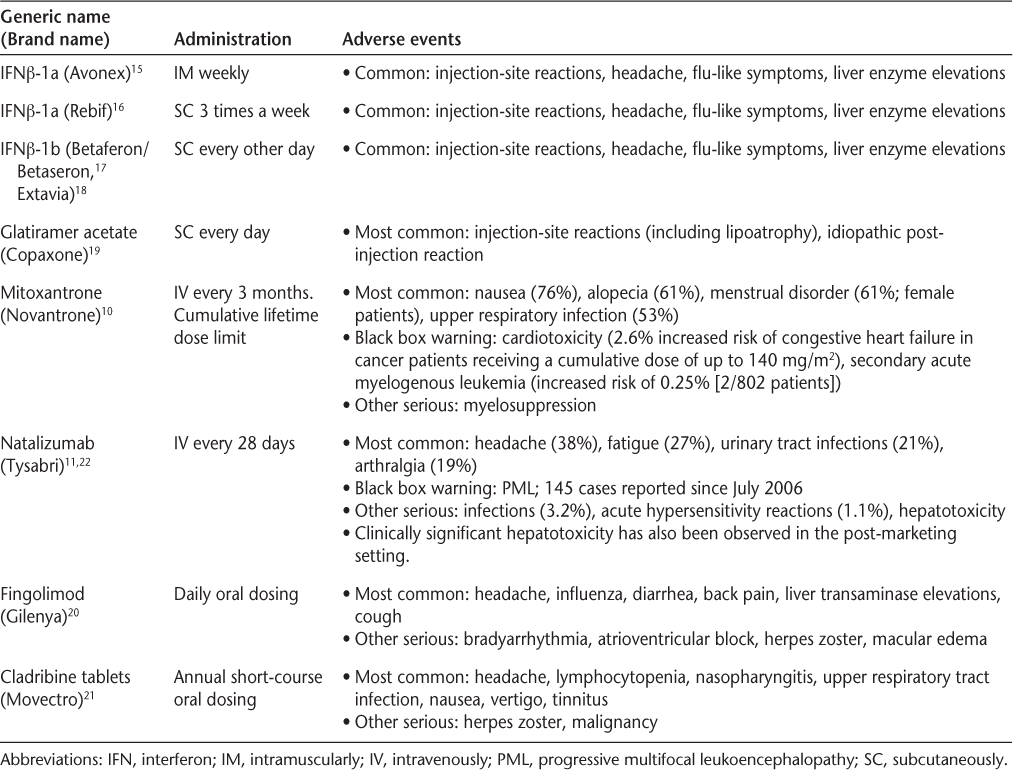

Existing therapies approved for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS (RRMS) include several beta-interferon preparations (such as Avonex,15 Rebif,16 Betaferon/Betaseron,17 and Extavia18), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone),19 mitoxantrone (Novantrone),10 and natalizumab (Tysabri).11 More recently, the first oral therapies for MS have been licensed in some countries; fingolimod (Gilenya) is approved in Russia and the United States,20 and cladribine tablets (Movectro) in Russia and Australia21 for the treatment of patients with RRMS (Table 1).

Approved therapies for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

The benefit/risk profiles of the parenterally administered MS therapies are generally well established, and such agents, with the exceptions of mitoxantrone and natalizumab, are considered suitable for long-term use. However, all currently approved DMDs for MS require regular, long-term administration, which has a number of implications. Adherence, defined by the World Health Organization as “the extent to which a person's behaviour—taking medication, following a diet and/ or executing lifestyle changes—corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider,”23 is a key issue and is considered suboptimal in patients with MS who are receiving immunomodulatory therapy. A recent survey investigating adherence to parenteral DMDs found that about 40% of patients were nonadherent (defined as missing one or more injections in the previous 4 weeks).24 Additional studies support this finding, reporting that 17% to 46% of patients with MS do not follow the prescribed dosing regimen for their treatment.25–28 Nonadherence can lead to poor treatment outcomes, long-term complications, and increased health-care costs.23 Rio et al.28 showed that patients with RRMS who discontinued therapy demonstrated significantly greater disability at follow-up compared with patients who remained on treatment. Furthermore, the proportions of patients who were relapse-free or progression-free were also significantly lower among patients who had discontinued therapy.

Factors that may have a negative impact on adherence include a perceived lack of efficacy, injection/ needle phobia, injection fatigue, depression and other psychological disorders, cognitive impairment, denial of illness, lifestyle disruption, forgetfulness, and unrealistic treatment expectations, as well as adverse events such as injection-site reactions (ISRs), pain, and flu-like symptoms.24 28–31 Additionally, patient-specific factors— including education levels, financial disparities, and religious and cultural beliefs—can also have an influence.30 32 Reasons cited by patients for nonadherence vary depending on the stage and severity of MS. For example, patients may experience adverse events while receiving treatment during periods of remission or during the early stages of the disease; at such times, patients may question the need for treatment. However, in the later, more severe, stages of MS, patients are more likely to stop using treatment because of a perceived lack of efficacy.30 33 With the new oral therapies, patient perceptions of poor efficacy and/or safety profiles compared with parenteral treatments may lead to an increased risk of poor treatment adherence in the form of missed or incorrect doses.

Because the causes of nonadherence to MS treatment regimens are complex and vary considerably from patient to patient, strategies for improving adherence require the participation of the entire health-care team. MS nurses are often the members of the health-care team with whom the patient has the closest connection and are generally readily accessible to the patient. As such, they play a pivotal role in encouraging adherence and are critical to the successful execution of adherence strategies.34 35

Strategies for Maximizing Adherence

Strategies developed and employed by nurses to enhance treatment adherence among their patients include establishing a trusting therapeutic relationship by ensuring effective communication and empathetic attention. Developing a collaborative therapeutic relationship with the patient that is open and honest from diagnosis (and even earlier in some cases) throughout the course of disease can contribute to the patient's confidence in the health-care team and in their ability to manage the disease.32 The quality and quantity of communication, as well as the amount of time spent with the patient, are also critical. MS nurses who devote the appropriate level of attention at clinically relevant times may enhance adherence by making the patient more informed, with the opportunity to discuss any concerns. A substantial amount of time is required in order to counsel and communicate effectively with the patient at clinically important times, such as initial diagnosis, treatment initiation, periods of relapse, development of adverse events, and treatment changes. The method of communication can also enhance adherence; for example, availability of the nurse by telephone can be reassuring if the patient is experiencing difficulties and may enable problems to be treated earlier or even prevented.

Specialist MS nurses also play a key role in patient education, helping patients and their families to better understand the MS disease process, the treatment and management options, and the ways in which early treatment can affect relapse and disability outcomes.36 Education can empower patients to feel more active in the management of their MS and may therefore enhance their motivation to adhere to treatment.14 36 Patient education is also important for establishing and managing treatment expectations.14 For example, it is important that patients who are in remission understand the need for treatment continuation and have realistic expectations of long-term therapy. Unrealistic treatment goals and expectations can lead to loss of patient motivation, which, again, reduces adherence. A study by Mohr et al.37 showed that approximately two-thirds of patients who discontinued their MS treatment had unrealistic expectations of treatment.

As patient advocates, MS nurses are a constant source of support, advice, and encouragement to their patients. Establishing a good rapport with the patient and providing up-to-date information about current research and developments can help the patient deal with the diagnosis and provide them with hope for the future. As a trusting relationship is developed with the patient, it becomes possible to discuss important personal issues, including sexuality, depression, and lifestyle-related factors. Using highly developed communication skills, MS nurses can reassure patients that they are not alone, reducing their feelings of isolation and increasing adherence. Depression is common in MS and is a major cause of loss of motivation and poor adherence to treatment.38 One study showed that, among MS-treated patients reporting new or increased depression, 86% of those who received psychotherapy or antidepressant medication continued their MS treatment, compared with only 38% of those who received no therapy for depression.38 This highlights the importance of discussing issues such as depression with the patient so that such problems can be more easily recognized, discussed, and treated.

The MS nurse also performs a key role in discussing treatment options with the patient (although the extent to which the MS nurse is involved in prescribing varies both across centers and across countries). Ensuring that the patient understands the available treatment options (both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) and the goals of treatment will lead to more informed decision-making by the patient and the health-care team. This can help the patient feel empowered, in control, and more motivated to adhere to the treatment regimen.14 32

Variations in the availability of treatments across countries can be frustrating for the patient and the MS nurse alike. With increased access to online information sites and forums, patients may ask their nurse about treatments that are not available in their country, and a considerable amount of time may be required to discuss these treatments. It is important that the patient be informed and reassured about the treatments that are available, and that the nurse takes an open and honest approach.

After treatment selection, MS nurses play an important role in supporting treatment administration—for example, advising the patient about the correct injection technique for a parenteral therapy.36 Many patients have concerns about self-injecting, such as needle phobia and injection anxiety, and nurses often need to counsel the patient to address these concerns. This counseling can take the form of reassurance about the safety of the injection, instruction in relaxation techniques, and discussion of techniques to reduce associated adverse events.39 Because of cognitive and other issues, some patients may require repeated coaching and follow-up, which can be extremely time-consuming for the health-care team. In addition, patients may experience ISRs or pain at injection sites, and nurses can be very effective in educating the patient, monitoring for such side effects, and advising about techniques to reduce these reactions. Several strategies have been employed to reduce the incidence of ISRs and the discomfort of manual injections, including the development of auto-injectors (such as electronic injection devices) and thinner needles; these developments have led to reduced incidences of adverse events and increased adherence.14 Such devices, coupled with nurse counseling and support, can lead to increased acceptance by patients, although the extent of the impact of these advances on treatment adherence is not yet known.

Adverse events can represent a major barrier to treatment adherence, and steps to reduce these undesirable effects can be discussed and implemented. The impact of adverse effects of parenteral therapies can be minimized by adopting specific strategies; for example, injecting before bedtime can allow unwanted symptoms to occur during sleep, when they may be less bothersome.32 The MS nurse can help by managing patient expectations concerning the potential severity and timing of such symptoms, by discussing management options, and by providing the reassurance that may be needed for the patient to continue treatment. Nurses also play a role in monitoring treatment outcomes in terms of relapses and disease progression, and are therefore well placed to advise patients on the risks that they may face as a result of nonadherence.

As the course of disease varies from patient to patient, so does the treatment regimen. Nurses are responsible for overseeing and monitoring the effects of each treatment regimen, including both DMD therapies and symptomatic treatments, throughout the course of disease. This means that nurses have to maintain regular contact with their patients to monitor outcomes and provide support, particularly during any treatment changes.

The Changing Treatment Landscape

Although MS is a treatable disease, it is generally recognized that a cure is not on the horizon, and a number of unmet needs remain with regard to currently available, long-term treatments. It remains to be seen whether novel agents, with simpler dosing schedules and routes of administration and possibly improved efficacy profiles, will lower the burden on patients and have a positive impact on long-term adherence.

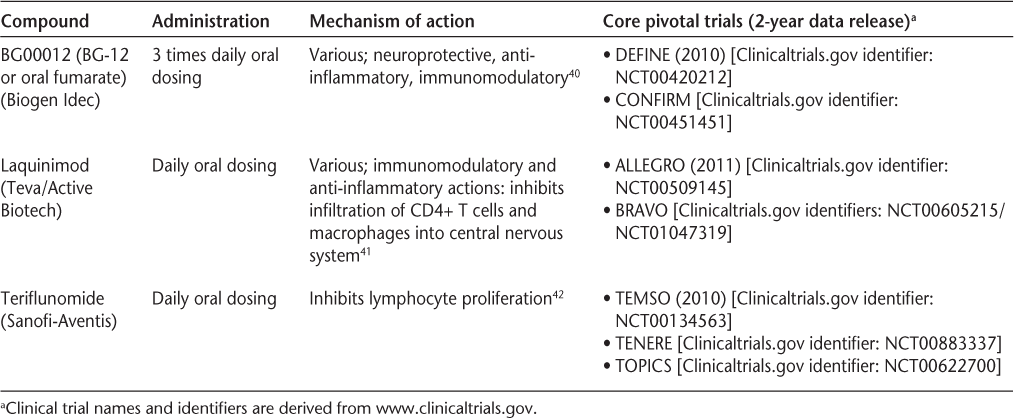

As mentioned previously, fingolimod and cladribine tablets have been approved in some countries for the treatment of patients with RRMS. New oral therapies still in development for MS include BG00012, laquinimod, and teriflunomide (Table 2). These agents could have a number of positive effects on patient management.38 Although transitioning to oral therapy is unlikely to eradicate nonadherence, the introduction of therapies perceived by patients as more “friendly” may make patients more likely to initiate and adhere to these regimens, which in turn may lead to improved long-term disease outcomes.33 Moreover, some therapies are currently being studied with annual dosing schedules, which would remove the demands for daily, weekly, or monthly treatment.35 43 44 Such treatments will likely require reminder systems and treatment calendars (patients may forget to schedule a return visit to the physician after a long period of nontreatment) and extra vigilance with hematologic safety monitoring.45 An important point to consider may be the perceived level of importance of oral versus parenteral therapies. Patients may consider oral therapies to be less important than parenteral ones, increasing the risk of nonadherence. This will likely require skillful and honest management by the MS nurse and other members of the health-care team prior to treatment initiation and throughout the course of treatment. Clearly, MS nurses must continue expanding their role as health-care professionals who are both knowledgeable about the MS treatment landscape and able to maintain close therapeutic bonds with their patients.

New oral therapies for multiple sclerosis in late-stage development

While these new oral treatments have the potential to improve adherence and efficacy, they may present a number of new challenges to the health-care team, and in particular to specialist MS nurses. First, there will be a demand for more professional education and training to ensure that nurses are familiar with the wider range of treatment options, including the specific dosing schedules, mechanisms of action, and benefit/risk profiles of each new therapy. Training will also need to be offered and updated regularly so that nurses are familiar with new research, developments, and drug approvals.45 Nursing organizations and country-specific nursing networks, such as the IOMSN, can provide educational and mentoring resources. In addition, it is essential that MS nurses have the opportunity to network with colleagues internationally in order to share their knowledge and experience as new treatments become more readily available worldwide.

Second, new therapies will undoubtedly affect the treatment decision-making process, as there will be more available therapies to discuss with the patient, and the relative merits and limitations of each option will have to be considered. Because of the variable course of MS, each patient requires an individualized treatment strategy that takes into account his or her disease course, lifestyle, and specific personal circumstances. Patients with MS who are considering having a family, for example, will require education regarding the implications of the available treatment options in terms of fertility, so that treatments can be selected that are most suitable in both the short and the long term.

Third, new treatments will require rigorous monitoring as part of risk-management plans to identify and manage any safety signals. For example, patients prescribed treatments that target lymphocytes will require regular hematologic monitoring throughout the course of therapy to minimize the risk of associated adverse events, such as lymphopenia, neutropenia, and infections.36 Others may require cardiovascular monitoring to limit the impact of dose-related adverse effects on cardiac tissue.46 In addition to these safety concerns, the monitoring and management of other potential adverse events may be a challenge; as with any new frontier, there will be uncharted territory because of the relatively unknown longer-term safety and tolerability profiles. This additional monitoring and management may be time-intensive and may require additional funding and other resources from the health-care team.

As patient advocates, nurses can facilitate the implementation of changes to the treatment algorithm during and following the inclusion of new therapies through effective communication, education, and management, including the provision of open forums for discussion and to manage expectations and address concerns. Nursing professionals already play an important role in the comprehensive MS health-care team, and their responsibilities and workload will further increase as novel treatment paradigms are established.

Conclusion

MS nurses play a crucial role in helping patients better understand their disease and treatment options as well as assisting with treatment initiation and management and encouraging long-term adherence to therapy. New oral therapies offer the potential for increased efficacy, tolerability, adherence, and convenience. The ongoing research and development associated with such treatments provides individuals living with MS with greater hope for their future. However, the emergence of new MS treatments and the resulting changes in the treatment paradigm will cause the skill set required of an MS nurse to expand and evolve to ensure appropriate care of the patient, both physically and psychologically, and to meet the monitoring needs specific to each therapy. Education and training for health-care professionals must adapt accordingly and be coordinated efficiently across the different disciplines within the health-care team. Furthermore, to reduce the burden of the treatment decision-making process, additional protocols and guidelines on current treatments and management strategies must be developed.

This is an exciting time in the management of MS. However, the implications of the new therapeutic developments for the health-care team, particularly the MS nurse, must be considered and appropriate professional development initiatives put in place. From an international perspective, it will be important for MS nurses to collaborate and publish their experiences with the new therapies to ensure that much-needed information and management strategies are disseminated to the global nursing community, for the ultimate benefit of both patients and MS health-care providers.

PracticePoints

MS nurses play an essential role in counseling and supporting patients with MS as well as assisting with treatment initiation, management, and monitoring, and encouraging long-term adherence to therapy.

The development of new MS therapies will have a dramatic impact on the role of the MS nurse, who will have increased responsibility for educating patients about the available treatment options, as well as performing the necessary management, support, and monitoring.

Professional development initiatives are needed to help MS nurses fulfill their changing responsibilities with the introduction of the new treatment options.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jason Gardner (of Merck Serono at the time of writing) for his assistance in facilitating the development of this manuscript. Editorial assistance from ACUMED was paid for by Merck Serono; specifically, the authors wish to thank Alex Millis (for medical writing support in drafting the manuscript) and Caroline Patrick and Alex Millis (for help incorporating revisions to the original submission), as well as Victoria Williams (for editorial services).

References

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2002;359:1221–1231.

Tullman MJ, Lublin FD, Miller AE. Immunotherapy of multiple sclerosis—current practice and future directions. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002; 39: 273–285.

Kappos L, Freedman MS, Polman CH, et al. Effect of early versus delayed interferon beta-1b treatment on disability after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: a 3-year follow-up analysis of the BENEFIT study. Lancet. 2007; 370: 389–397.

Comi G, Filippi M, Barkhof F, et al. Effect of early interferon treatment on conversion to definite multiple sclerosis: a randomised study. Lancet. 2001; 357: 1576–1582.

Jacobs LD, Beck RW, Simon JH, et al.; CHAMPS Study Group. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343: 898–904.

Revel M. Interferon-beta in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Pharmacol Ther. 2003; 100: 49–62.

Chofflon M, Ben-Amor AF. Long-term benefits of early and high doses of interferon beta-1a treatment in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2002; 104: 244–248.

Comi G, Martinelli V, Rodegher M, et al. Effect of glatiramer acetate on conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (PreCISe study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009; 374: 1503–1511.

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–1517.

Merck Serono/EMD Serono. Novantrone® US Prescribing Information. http://www.novantrone.com/assets/pdf/novantrone_prescribing_info.pdf. Accessed September 2010.

Biogen Idec. TYSABRI® (natalizumab) Injection—Prescribing Information. www.tysabri.com. Accessed September 14, 2009.

Halper J, Holland N. An overview of multiple sclerosis. In: Halper J, Holland N. Comprehensive Nursing Care in Multiple Sclerosis. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2002.

Uccelli MM, Fraser C, Battaglia MA, Maloni H, Wollin J. Certifica-Certification of multiple sclerosis nurses: an international perspective. Int MS J. 2004; 11: 44–51.

Lugaresi A. Addressing the need for increased adherence to multiple sclerosis therapy: can delivery technology enhance patient motivation? Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009; 6: 995–1002.

Biogen Idec. Avonex® (interferon beta-1a) US Prescribing Information. http://www.avonex.com/_additional/prescribe_info_med_guide.xml. Accessed September 2010.

Merck Serono/EMD Serono. Rebif® (interferon beta-1a) US Prescribing Information. http://www.emdserono.com/cmg.emdserono_us/en/images/rebif_tcm115_19765.pdf. Accessed September 2010.

Berlex Laboratories. Betaseron® (interferon beta-1b) US Prescribing Information. http://www.betaseron.com/prescribing_info.jsp. Accessed September 2010.

Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Extavia® (interferon beta-1b) US Prescribing Information. http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/extavia.pdf. Accessed September 2010.

Teva Pharmaceuticals. Copaxone® (glatiramer acetate) Prescribing Information. February 2009. http://www.copaxone.com/pdf/PrescribingInformation.pdf. Accessed September 2010.

Novartis AG. Gilenya® (fingolimod) Prescribing Information. September 2010. http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/gilenya.pdf. Accessed September 2010.

Merck Serono. Movectro® (cladribine tablets) Product Information. September 2010. http://www.merckserono.com/en/index.html. Accessed September 2010.

Goodin D. The return of natalizumab: weighing benefit against risk. Lancet Neurol. 2006; 5: 375–377.

World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s4883e/s4883e.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2009.

Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A, et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol. 2009; 256: 568–576.

Tremlett HL, Oger J. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology. 2003; 61: 551–554.

Portaccio E, Zipoli V, Siracusa G, Sorbi S, Amato MP. Long-term adherence to interferon beta therapy in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2008; 59: 131–135.

O'Rourke KE, Hutchinson M. Stopping beta-interferon therapy in multiple sclerosis: an analysis of stopping patterns. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 46–50.

Rio J, Porcel J, Tellez N, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 306–309.

Cox D, Stone J. Managing self-injection difficulties in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006; 38: 167–171.

Cohen B. Adherence to disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2006;(Feb suppl):32–37.

Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Likosky W, Levine E, Goodkin DE. Injectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self-inject. Ann Behav Med. 2001; 23: 125–132.

Brandes DW, Callender T, Lathi E, O'Leary S. A review of disease-modifying therapies for MS: maximizing adherence and minimizing adverse events. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009; 25: 77–92.

Cohen BA, Rieckmann P. Emerging oral therapies for multiple sclerosis. Int J Clin Pract. 2007; 61: 1922–1930.

Holland N, Wiesel P, Cavallo P, et al. Adherence to disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis: part II. Rehabil Nurs. 2001; 26: 221–226.

Holland N, Wiesel P, Cavallo P, et al. Adherence to disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis: part I. Rehabil Nurs. 2001; 26: 172–176.

Costello K, Sipe JC. Cladribine tablets' potential in multiple sclerosis treatment. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008; 40: 275–280.

Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, et al. Therapeutic expectations of patients with multiple sclerosis upon initiating interferon beta-1b: relationship to adherence to treatment. Mult Scler. 1996; 2: 222–226.

Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, Gatto N, Baumann KA, Rudick RA. Treatment of depression improves adherence to interferon beta-1b therapy for multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1997; 54: 531–533.

Costello K, Kennedy P, Scanzillo J. Recognizing nonadherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. Medscape Med J. 2008; 10:225.

Kappos L, Gold R, Miller DH, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIb study. Lancet. 2008; 372: 1463–1472.

Comi G, Pulizzi A, Rovaris M, et al. Effect of laquinimod on MRI-monitored disease activity in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIb study. Lancet. 2008; 371: 2085–2092.

Tallantyre E, Evangelou N, Constantinescu CS. Spotlight on teriflunomide. Int MS J. 2008; 15: 62–68.

Giovannoni G, Comi G, Cook S, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral cladribine for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362: 416–426.

Fox W. Sustained positive effects of alemtuzumab on diverse neurological functions in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. Poster presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology; April 10–17, 2010; Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Smrtka J. Lymphocyte-targeted therapy as an emerging treatment paradigm: management considerations. Int J MS Care. 2008; 10: 11–17.

Kappos L, Radue EW, O'Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362: 387–401.

Financial Disclosures: Ms. Burke has been part of the clinical trials/research programs team for Genzyme, Actelion, Merck Serono, and Bayer Schering Pharma. She has received MS nurse clinic funding support from Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, Bayer Schering Pharma, and Biogen Idec. Ms. Dishon has received consulting fees from Merck Serono for participation in a meeting. Ms. McEwan has received consulting fees and honoraria from Teva Neurosciences (now Teva Canada Innovations), EMD Serono (Canada), Biogen Idec, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. Ms. Smrtka has received consulting fees and honoraria from EMD Serono, Pfizer Inc, Teva Neurosciences, Novartis, Bayer Healthcare Inc, Acorda Therapeutics, Biogen Idec, and Questcor, and has served on the speakers' bureau for Questcor.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by Merck Serono S.A.−Geneva, Switzerland, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.