Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Participation as an Outcome in Multiple Sclerosis Falls-Prevention Research

Author(s):

Selecting the outcomes for an intervention trial is a key decision that influences many other aspects of the study design. One of the major tasks during the 3-day inaugural meeting of the International MS Falls Prevention Research Network was to identify the key outcomes for the falls-prevention intervention that was being designed by the Network members for testing across their multiple sites. Through a nominal group process, meeting participants described how engagement in important, meaningful everyday activities, beyond traditional basic and instrumental activities of daily living, should be a long-term outcome of a successful falls-prevention intervention for people with MS. Post-meeting work, which involved literature reviews and comparisons of definitions of major constructs identified during the meeting discussions, led to the consensus recommendation of including participation as a long-term outcome in MS falls-prevention interventions. Participation reflects involvement in a life situation. This article explains the rationale for this recommendation and presents four measures that have the potential for use in tracking long-term participation outcomes in MS falls-prevention research.

Selecting the outcomes for an intervention trial is a key decision that influences many other aspects of the study design. Outcomes are the changes that are expected to occur among the targeted participants as a result of engagement in the intervention. Changes may emerge at various points during, immediately after, or several weeks or months following intervention delivery and are determined by comparing measures taken at these points to the ones taken at baseline. Failure to select an outcome that is appropriately matched to the intervention, in terms of content and expected mechanism of action, can result in nonsignificant results or inability to interpret the findings obtained.

In keeping with this knowledge, one of the major tasks during the 3-day inaugural meeting of the International MS Falls Prevention Research Network was to identify the key outcomes for the falls-prevention intervention that was being designed by the Network members for testing across their multiple sites. Selecting outcomes was just one of multiple protocol-related decisions addressed during the 3-day meeting. The discussions and debates on this topic addressed the potential outcomes for multiple sclerosis (MS) falls-prevention interventions, their pros and cons, and issues around their measurement and use in an international, multisite study.

The discussions started on the first day with a panel presentation by Matsuda, Cattaneo, and Peterson,1 which challenged meeting participants to consider the potential outcomes of an MS falls-prevention intervention in terms of type (ie, primary, secondary, tertiary) and sequence (ie, immediate post-intervention, short-term, long-term). In addition, these speakers asked participants to consider outcomes broadly, using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as an organizing framework.2 The ICF is a biopsychosocial model that synthesizes biological, individual, and social perspectives of health and views disability and functioning as the result of interactions between health conditions and contextual factors.2 After the panel presentation, further input by Gunn3 noted that the selection of outcomes must also consider, for example, being comprehensive without being burdensome; finding a balance between breadth and depth; and balancing accuracy versus clinical applicability.

Work on the second and third days of the meeting led to the decision to include participation as a secondary, long-term outcome in the protocol for the MS falls-prevention intervention trial being developed by the Network. Participation is one component of functioning and is defined in the ICF2 as “involvement in a life situation” (p. 10). A secondary outcome is an endpoint that is used to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention, beyond the one that is most important (ie, reducing falls). This article will focus on the rationale for including participation as an outcome, based on the consensus process used during the meeting and the subsequent discussions and reviews of the literature. In addition, four measures that have the potential for use in the Network's emerging protocol will be described.

Background

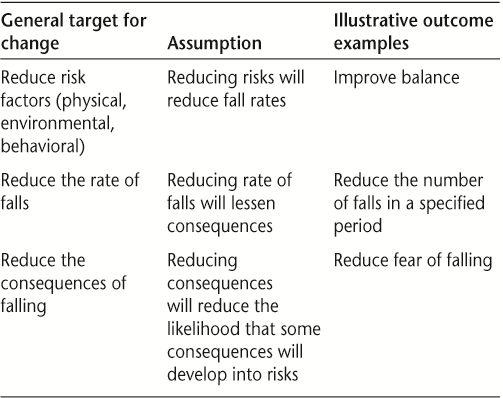

Falls and their related consequences are a significant problem in people with MS, with reported fall rates ranging from 50% to 52%4 5 to as high as 70%.6 Recurrent falls are also a concern in this population, as are injurious falls.7 There are numerous risk factors for falls among people with MS,6 as well as numerous consequences. Some consequences are immediate (eg, an injury), while others develop over time and may actually become risk factors for subsequent falls (eg, fear of falling, activity restriction).8 Reducing the rate of falls is a key outcome for any falls-prevention intervention. In addition, minimizing risk factors and consequences are also commonly considered as important outcome targets (Table 1).

Conceptualizing outcomes for multiple sclerosis falls-prevention intervention trials

Across the MS falls-prevention intervention studies to date, outcomes have focused primarily on reducing risk factors (eg, balance impairment, leg weakness) and reducing the rate of falls.9–11 There has also been some interest in reducing the consequences of falls through the application of self-management principles.12 Despite the face validity of these outcomes, we intentionally challenged ourselves during the Network meeting to ask: “Are these outcomes enough? Is anything missing? Do these outcomes capture the changes that are most valued by people with MS and other stakeholders?” In particular, we questioned whether a broader, more long-term outcome was needed to fully evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of an MS falls-prevention intervention. How these discussions and the subsequent work evolved is the focus of the remainder of this article.

Consensus-Building Process and Results

There are several systematic methods that can be used to build consensus. One of the most common face-to-face methods is the nominal group technique, which was developed by Van de Ven and Delbecq in the late 1960s.13 The nominal group technique is a structured brainstorming approach that can be used to define problems, identify solutions, and set priorities for action. The technique is time- and cost-efficient, requires little preparation on the part of participants, allows for in-session completion and dissemination of results, and allows for equal representation of all individuals involved.14 Typically, five steps are followed: 1) Introduction and explanation of the task at hand, 2) Independent generation of ideas, 3) Sharing of ideas, 4) Group discussion and clarification, and 5) Voting or ranking of ideas.

Introducing the Task of Selecting Outcome Measures (Step 1)

The panel presentation on the first day of the meeting, which was described in the introduction of this article, familiarized the meeting participants with the task of selecting outcome measures for the protocol of the MS falls-prevention intervention. The panel speakers reviewed the ICF2; provided examples to differentiate potential falls-related outcomes at the level of impairment (body structures and functions), activity, and participation; and discussed types, timing, and sequencing of outcomes. Additional issues that were raised for consideration included feasibility, cost, transferability to clinical practice, the role of the intervention setting, and potential measurement confounders (eg, time of day, season, lifestyle factors). Confounding variables are those that are correlated with both the dependent (change) and independent (intervention) variable.

Several potential outcomes were presented for debate—for example, rate of injurious falls and engagement in falls-prevention behaviors. Subsequent discussions focused on addressing modifiable fall risk factors, particularly balance and cognitive attention to mobility, both of which are consistent with the literature.15 As discussions evolved, there was recognition that these outcomes were likely to occur more proximal to intervention and that broader, longer-term outcomes were also needed. The individuals engaged in these discussions included MS falls-prevention researchers (n = 9), researchers from related areas (n = 3), representatives from MS and professional organizations (n = 3), local MS specialist clinicians (n = 4), falls-prevention experts from the local public health department (n = 2), people affected by MS (n = 3), and trainees (n = 4).

Generating and Sharing (Steps 2 and 3)

On Day 2, after everyone had time to consider the presentations and discussions from the previous day, participants were each asked to identify the top three outcomes they felt were the most important to address and evaluate through a new MS falls-prevention intervention. Flip charts were positioned around the room for the lists. Independently, meeting participants added their outcome choices to the lists.

Discussing and Clarifying Ideas (Step 4)

Once all participants had contributed to the outcome list, discussions ensued to clarify ideas, terms, and meanings. Several item clusters emerged, one of which used terms such as participation, quality of life, life satisfaction, activity engagement, and physical activity levels. Meeting participants described how engagement in important, meaningful everyday activities was at the core of their thinking, and went far beyond traditional basic and instrumental activities of daily living (eg, bathing, dressing, shopping) as well as simply being more physically active. Participants talked about how a successful falls-prevention intervention would enable and empower people with MS to choose and engage in activities that are important and meaningful in their lives while simultaneously reducing risk of falls. Engagement would occur by people with MS making autonomous and active decisions to change the way important activities are done, with whom, where, and how. These choices may lead to more activity, while in other cases they might lead to less or different activity.

Voting (Step 5)

After clarifying ideas and selecting terms, participants voted on the three outcomes they felt were most important to measure as part of the protocol being developed by the Network. The cluster of items related to participation, quality of life, and life satisfaction received the second-highest number of votes for inclusion in the protocol. The highest number of votes was for reducing the number of falls. The third-highest was for dynamic balance. These outcomes are addressed in other articles in this special issue.16 17

Post-Meeting Work

Since a cluster of related items was identified at the March 2014 meeting, the first task afterwards was to determine which term best fit with the intentions expressed during step 4 of the nominal group process. Therefore, definitions were sought for the terms “quality of life,” “health-related quality of life,” “life satisfaction,” and “participation.” Many definitions were identified. The following ones were selected for most closely reflecting the discussions at the meeting:

Quality of life: “The degree to which a person enjoys the important possibilities of his or her life,” which includes who one is (being), connections with one's environment (belonging), and achieving personal goals, hopes, and aspirations (becoming).18

Health-related quality of life: “A multi-dimensional concept that includes domains related to physical, mental, emotional and social functioning. It goes beyond direct measures of population health, life expectancy and causes of death, and focuses on the impact health status has on quality of life.”19

Life satisfaction: “How people evaluate their life as a whole rather than their current feelings . . . a reflective assessment of which life circumstances and conditions are important for subjective well-being.”20

Participation: “Involvement in life situations which includes being autonomous to some extent or being able to control your own life, even if one is not actually doing things themselves. This means that not only the actual performance should be the key indicator, but also the fulfillment of personal goals and societal roles” (p. 578).21

A careful review of these definitions indicated that only the participation definition explicitly included language capturing the notion of choice and control, and acknowledged the importance of goals and roles in addition to actual performance. These components were consistent with the discussions about enabling and empowering individuals with MS to choose and engage in activities that are important and meaningful in their lives while simultaneously reducing risk of falls. As a consequence, participation was determined to be the best-fitting term for the expected long-term outcome of an MS falls-prevention intervention trial.

After selecting participation as the outcome construct, key literature in the area of participation was reviewed, input from experts in disability-focused participation research was sought, and the authors of this article reflected on their own experience with and use of participation-related outcome measures. The review and input supported the relevance of participation as a long-term outcome for an MS falls-prevention intervention trial given the recent trends in health care and rehabilitation regarding outcomes and accountability; findings related to participation in MS falls research to date; recognition of the importance of having long-term outcomes that have meaning for people with MS; and the fact that there are valid and reliable measures of participation available for MS research and clinical use.

With respect to recent trends, the ICF has become the standard for disablement language. It portrays human function and decreases in functioning as the product of a dynamic interaction between various health conditions and contextual factors (ie, environmental and personal factors).2 The ICF identifies three levels of human function: functioning at the level of body or body parts, the whole person, and the whole person in his or her complete environment. These levels, in turn, contain three domains of human function: body functions and structures, activities, and participation.2

The ICF's attention to participation has led to increasing recognition that high-quality health care looks beyond mortality and disease to focus on how people live with their conditions within their environments. As a result, health-care providers and researchers are increasingly expanding their measurement focus to include participation.22 The universal, standardized language of the ICF, as well as its utility for problem-solving within rehabilitation clinical care,23 suggests that including participation as an outcome in research will support translation of evidence-based interventions. This translation will be critical for the long-term success of the efforts of the Network members.

Although to our knowledge participation has never been studied in MS falls-prevention research, fear of falling or concerns about falls among people with MS has been linked to several variables likely to be associated with participation. These include future physical activity and activity curtailment.8 24 In a cross-sectional study undertaken by Peterson and colleagues8 that involved 1064 individuals with MS, aged 45 to 90 years, 63.5% of the study participants reported fear of falling. Among these individuals, 82.6% reported curtailing activity. In their survey of 575 community-dwelling people with MS, Matsuda and colleagues24 found that 70.5% of 546 participants reported limiting their activity because of concerns about falling. These findings warrant concern because prospective research involving community-dwelling older adults suggests that people who are afraid of falling enter a debilitating spiral of loss of confidence, restriction of physical activities and social participation, physical frailty, falls, and loss of independence.25 Furthermore, studies show that people who limit activity because of fear of falling are at particularly high risk of becoming fallers.25

Findings from qualitative research involving people with MS also point to the importance of exploring the impact of falls on participation. Peterson et al.26 undertook a phenomenological study to explore and describe the lived experience of falls self-efficacy (ie, perceived confidence to avoid a fall during basic activities of daily living) among six individuals with MS. The analysis generated a meaning structure of the lived experience of falls self-efficacy that consisted of the one overarching theme: managing fall risk as a means of supporting activity. For the study participants, managing fall risk was not an end in itself. Rather, it was a means of being able to continue involvement in valued and interesting activities.26 The activities described by study participants as being important to them were extremely individualized, reflecting their personal identities, roles, and responsibilities. Interestingly, each of the six study subjects reported that participating in activities enabled them to develop or maintain the strategies and physical capabilities needed to reduce fall risk.26 This finding suggests that participation may be an outcome of fall interventions, as well as a variable negatively associated with fall risk.

The hypothesis that participation is protective against fall risk is supported by prospective research involving community-dwelling older adults conducted by Delbaere and colleagues.27 Those investigators identified a “stoic” group of their study participants (100/500, 20% of the study population). The stoic group had a high physiological risk but low perceived fall risk, which was protective for falling and mediated through a positive outlook on life (P = .001) and maintained physical activity and community participation (P = .048). The psychological profile of stoics did not indicate excessive risk-taking behavior but rather a positive attitude to life, emotional stability, and low reactivity to stress.27

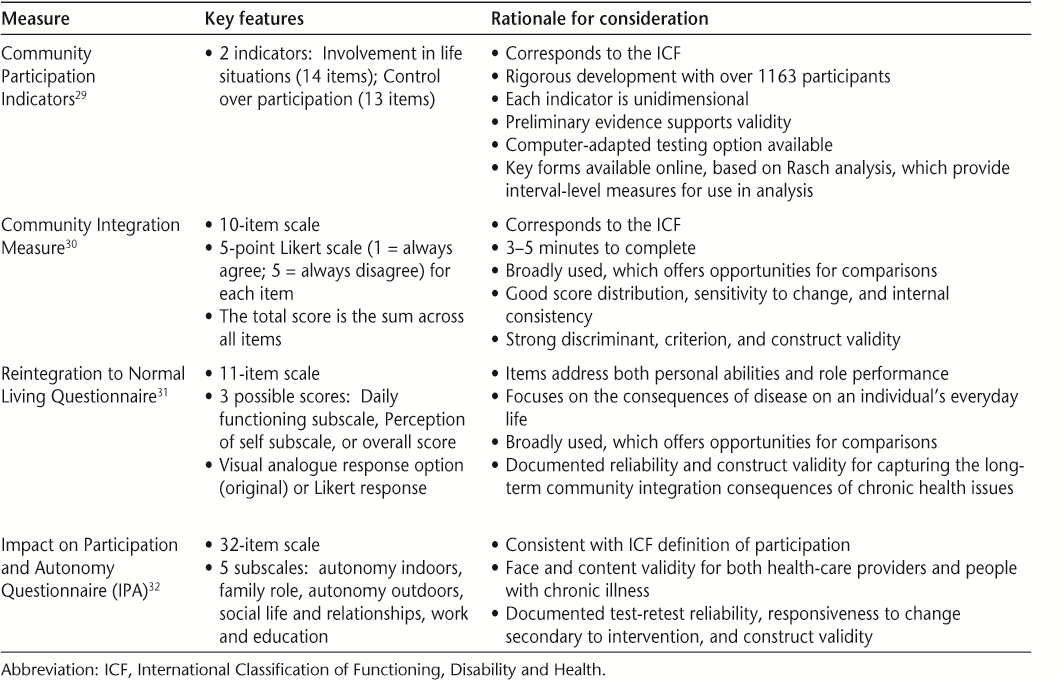

Outcomes at the level of participation are “real world” outcomes, meaning that they are relevant and meaningful to the daily lives and long-term needs of individuals with disabilities. Although rehabilitation providers have traditionally focused on conceptualizing outcomes at the level of impairment (body functions and structures) or disability (activity), the importance of focusing on “real world” participation outcomes in research and practice has been emphasized for at least 20 years.28 Perhaps as a consequence of this emphasis, there are a number of participation measures that have been validated for use with people with MS. The four self-report measures that our group identified as having the greatest potential for application in the Network's MS falls-prevention intervention protocol are summarized in Table 2. The factors contributing to these selections are provided in the last column of the table.

Participation measures with potential for inclusion in a multiple sclerosis falls-prevention intervention protocol

Each of the measures presented in Table 2 has strengths and limitations and will require further, in-depth evaluation by the members of the Network. This evaluation will need to consider potential issues related to use across multiple sites and countries, need for language translation, item correspondence to falls-prevention intervention content, and the types of interventions to which these instruments have been sensitive to change. For now, we know that all of these instruments have good psychometric properties, have included people with MS in the development and testing research, and have conceptual links to the ICF. For these reasons, each merits further consideration for use in the Network's falls-prevention intervention protocol.

Conclusion

The participants of the inaugural meeting of the International MS Falls Prevention Research Network, which included researchers, clinicians, and people with MS, agreed that participation is an important and relevant long-term outcome of a falls-prevention intervention. “Participation” has been selected as the overarching term, as it captures the notions of engagement in important, meaningful everyday activities yet goes beyond traditional basic and instrumental activities of daily living as well as just physical activity. In addition, this term is consistent with ideas of autonomy, active decision-making, and empowerment, all of which were identified during the Network meeting as relevant to the intervention we are currently developing.

Trends in practice and research support the decision to include participation as an outcome in an MS falls-prevention intervention protocol. Participation reflects a “real world” outcome that is meaningful in the daily lives of people with disabilities, including those with MS. Which specific measure should be used to capture this outcome has not yet been determined, but promising options have been identified. The next steps for the Network members are to carefully review and discuss the specific items within each of the candidate tools and critically evaluate the extent to which we believe our intervention can “move” the scores produced by these items. Given that our MS falls-prevention intervention protocol will be tested across multiple, international sites, further consideration will have to be given to issues of language translation and cultural relevancy of items.

PracticePoints

Nominal group method is useful for reaching consensus during collaborative efforts to advance rehabilitation research.

Participation is an important secondary long-term outcome for MS falls-prevention intervention trials.

Promising measures of participation that require careful evaluation for their potential use in MS falls-prevention intervention trials include the Community Participation Indicators, Impact on Participation and Autonomy Questionnaire, Community Integration Measure, and Reintegration to Normal Living Questionnaire.

References

Matsuda PN, Cattaneo D, Peterson E. Advancing MS fall prevention research: primary, secondary and tertiary outcomes [panel presentation]. Paper presented at: International MS Falls Prevention Research Network Meeting; 2014; Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

Gunn HJ. Advancing MS fall prevention research: primary, secondary and tertiary outcomes [invited response]. Paper presented at: International MS Falls Prevention Research Network Meeting; 2014; Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Cattaneo D, De Nuzzo C, Fascia T, Macalli M, Pisoni I, Cardini R. Risks of falls in subjects with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002; 83: 864–867.

Finlayson ML, Peterson EW, Cho CC. Risk factors for falling among people aged 45 to 90 years with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1274–1279; quiz 1287.

Gunn HJ, Newell P, Haas B, Marsden JF, Freeman JA. Identification of risk factors for falls in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2013; 93: 504–513.

Peterson EW, Cho CC, von Koch L, Finlayson ML. Injurious falls among middle aged and older adults with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008; 89: 1031–1037.

Peterson EW, Cho CC, Finlayson ML. Fear of falling and associated activity curtailment among middle aged and older adults with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 1168–1175.

Cattaneo D, Jonsdottir J, Zocchi M, Regola A. Effects of balance exercises on people with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2007; 21: 771–781.

Cattaneo D, Jonsdottir J, Regola A, Carabalona R. Stabilometric assessment of context dependent balance recovery in persons with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled study. J Neuroengineer Rehabil. 2014; 11:100.

Sosnoff JJ, Finlayson M, McAuley E, Morrison S, Motl RW. Home-based exercise program and fall-risk reduction in older adults with multiple sclerosis: phase 1 randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2014; 28: 254–263.

Finlayson M, Peterson EW, Cho C. Pilot study of a fall risk management program for middle aged and older adults with MS. NeuroRehabilitation. 2009; 25: 107–115.

Van de Ven AH, Delbecq AL. The nominal group as a research instrument for exploratory health studies. Am J Public Health. 1972; 62: 337–342.

Harvey N, Holmes CA. Nominal group technique: an effective method for obtaining group consensus. Int J Nurs Pract. 2012; 18: 188–194.

Porosińska A, PierzchaŁa K, Mentel M, Karpe J. Evaluation of postural balance control in patients with multiple sclerosis: effect of different sensory conditions and arithmetic task execution: a pilot study. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2010; 44: 35–42.

Coote S, Sosnoff JJ, Gunn H. Fall incidence as the primary outcome in multiple sclerosis falls-prevention trials: recommendation from the International MS Falls Prevention Research Network. Int J MS Care. 2014; 16: 178–184.

Cattaneo D, Jonsdottir J, Coote S. Targeting dynamic balance in falls-prevention interventions in multiple sclerosis: recommendations from the International MS Falls Prevention Research Network. Int J MS Care. 2014; 16: 198–202.

Quality of Life Research Unit, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto. Quality of Life Model. http://sites.utoronto.ca/qol/qol_model.htm. Accessed July 7, 2014.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Health Related Quality of Life and Well-being. HealthyPeople.gov. 2014. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/qolwbabout.aspx. Accessed July 7, 2014.

OECD Better Life Index. Life Satisfaction. 2014. http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/life-satisfaction/. Accessed July 7, 2014.

Perenboom RJ, Chorus AM. Measuring participation according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Disabil Rehabil. 2003; 25: 577–587.

Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, Whiteneck G, Bogner J, Rodriguez E. What does participation mean? an insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2008; 30: 1445–1460.

Steiner WA, Ryser L, Huber E, Uebelhart D, Aeschlimann A, Stucki G. Use of the ICF model as a clinical problem-solving tool in physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine. Phys Ther. 2002; 82: 1098–1107.

Matsuda PN, Shumway-Cook A, Ciol MA, Bombardier CH, Kartin DA. Understanding falls in multiple sclerosis: association of mobility status, concerns about falling, and accumulated impairments. Phys Ther. 2012; 92: 407–415.

Friedman SM, Munoz B, West SK, Rubin GS, Fried LP. Falls and fear of falling: which comes first? a longitudinal prediction model suggests strategies for primary and secondary prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002; 50: 1329–1335.

Peterson E, Kielhofner G, Tham K, von Koch L. Falls self-efficacy among adults with MS: a phenomenological study. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2010; 30: 148–157.

Delbaere K, Close JC, Brodaty H, Sachdev P, Lord SR. Determinants of disparities between perceived and physiological risk of falling among elderly people: cohort study. BMJ. 2010; 341:c4165.

Whiteneck GG. The 44th Annual John Stanley Coulter Lecture. Measuring what matters: key rehabilitation outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994; 75: 1073–1076.

Heinemann AW, Lai JS, Magasi S, et al. Measuring participation enfranchisement. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011; 92: 564–571.

McColl MA, Davies D, Carlson P, Johnston J, Minnes P. The community integration measure: development and preliminary validation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001; 82: 429–434.

Wood-Dauphinee S, Williams JI. Reintegration to normal living as a proxy to quality of life. J Chron Dis. 1987; 40: 491–499.

Cardol M, de Haan RJ, van den Bos GA, de Jong BA, de Groot IJ. The development of a handicap assessment questionnaire: the Impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA). Clin Rehabil. 1999; 13: 411–419.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Finlayson is a member of the editorial board of the IJMSC.

Funding/Support: This work was supported, in part, by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Planning Grant (Funding Reference Number 129594).