Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Change in the Health-Related Quality of Life of Multiple Sclerosis Patients over 5 Years

This study examined whether multiple sclerosis (MS) patients (N = 3779) experience change in their perceived health-related quality of life (HRQOL) over a 5-year period, and investigated baseline factors that may be related to change in HRQOL. Data from the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry were used to address the study's research questions. Results for the physical and mental component scores of the 12-item Short Form Health Status Survey, version 2 (SF-12v2), indicated that most of the MS sample experienced no significant changes over a 5-year period. However, 40% and 36% of the sample experienced clinically significant declines in their physical and mental HRQOL, respectively, over the 5-year period. After controlling for baseline scores, having a lower education, having greater duration since disease diagnosis, not being employed, having a lower income, not receiving a disease-modifying therapy, and taking a greater number of prescription medications were significantly associated with a clinically significant decline in physical HRQOL. After controlling for baseline scores, not being married/partnered, experiencing a greater number of relapses, not being employed, having a lower income, and taking a greater number of prescription medications were significantly associated with a clinically significant decline in mental HRQOL. Overall, most of the MS sample remained stable in their HRQOL over time. However, approximately four out of every ten patients experienced a clinically important decline in their HRQOL. While the association was statistically significant, the sociodemographic and disease-related factors linked with decline did not strongly predict decline over a 5-year period.

As one of the leading causes of neurologic disability in young adults, multiple sclerosis (MS) has enormous implications for the current and future health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of people diagnosed with this disease.1 Several studies have been conducted regarding the HRQOL of MS patients using a cross-sectional study design. These studies have demonstrated a lower HRQOL among MS patients than in the general population1–5 and in those with other chronic conditions.1 6 Some studies examined the overall HRQOL of MS patients, while other studies separated physical from mental HRQOL. Evidence from cross-sectional studies showed varied results regarding the relationship between sociodemographic or disease factors and physical or mental HRQOL of MS patients. A number of studies have found that physical HRQOL is related to age,1 2 4 7 gender,7 marital status,1 education level,1 2 4 employment,1 4 7 income,1 2 duration of disease,4 medication use,2 use of a disease-modifying therapy (DMT),1 4 relapses,1 7 depression,2 4 and use of support services.2 Others have found that mental HRQOL is related to age,1 4 8 marital status,1 education level,1 employment,1 income,1 2 duration of disease,4 9 10 relapses,1 and depression.2 4 Unfortunately, the research is not consistent in that sometimes the above factors do not show a significant relationship to HRQOL. For example, Schwartz and Frohner9 found that gender, age, marital status, education, and employment were not related to HRQOL.

While several cross-sectional studies on HRQOL have been conducted, very few studies have measured change in HRQOL over time. These longitudinal studies indicated that HRQOL may decline, remain stable, or improve, depending on the domain of HRQOL assessed.3 10–12 Of the investigations that examined the relationships among sociodemographic and disease factors and HRQOL over a 2-, 5-, or 8-year period, the results varied. Baseline HRQOL scores,10 changes in neurologic functioning,10 and use of nursing services13 were found to be related to changes in HRQOL, while age at onset/diagnosis,3 13 education level,13 and employment13 were not. Disease duration and gender were found in some studies10 13 to be related to HRQOL changes and in others3 13 to be unrelated.

Thus, the evolution of HRQOL over time in people with MS is unclear. A limited number of longitudinal studies with varying lengths of follow-up have shown varied results. The purpose of this study was to examine whether MS patients experience change in HRQOL over a 5-year period, and what baseline factors are related to change in HRQOL, using a larger sample than used in prior longitudinal studies.

Methodology

Sample

The study population was a convenience sample drawn from the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry. NARCOMS was established by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) in 1993 as a means for patients with MS to provide confidential information about the course of their disease and treatment in order to facilitate global, multicenter research on MS.14 People with MS are invited to enroll in the Registry through direct mailings, MS center outreach, support groups, and the NARCOMS website.14 Data are collected via questionnaires twice a year, 6 months apart. In the fall of 2003, NARCOMS began to collect biannual longitudinal HRQOL information from its Registry participants. This was used as the baseline measure in the current study. Survey results from the fall of 2008 were used as the comparison measure to examine possible changes over a 5-year period. On each survey, respondents were asked to report their HRQOL within the prior 4 months. All participants were over 18 years of age at baseline (2003).

The NARCOMS Registry is approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Western Institutional Review Board. Participants give permission for their information to be used for research purposes.15 Ethical approval to conduct this particular study was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Alberta.

Outcome

HRQOL was measured using a shortened generic HRQOL instrument derived from the well-validated and widely used 36-item Short Form Health Status Survey (SF-36).16 17 The 12-item Short Form Health Status Survey, version 2 (SF-12v2), standard form provides two summary scores: a Physical Component Score (PCS) and a Mental Component Score (MCS). General population standardized scores for both the PCS and MCS range from 0 (worst) to 100 (best), with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. Patients are asked to complete 12 questions regarding their perception of their physical, mental, and social health over the preceding 4 months. Test-retest reliability was reported as 0.88 to 0.89 for the PCS and 0.76 to 0.78 for the MCS for the SF-12v1,18 while internal consistency was 0.89 for the PCS and 0.86 for the MCS for the SF-12v2.17 The SF-12v2 showed high concurrent and construct validity scores when compared with the SF-36 and SF-12v1.17 Although the SF-12v2 has not been assessed for responsiveness in the MS population, the SF-36 has been shown to be moderately responsive to rehabilitation intravenous steroids in mixed ambulatory and nonambulatory MS samples,19 which are similar to the participants in the NARCOMS Registry. The NARCOMS questionnaires use the SF-12v2 because of its brevity. A difference in score of 3 points is considered clinically significant (John E. Ware, Jr, PhD, written communication, March 2011).

Factors Evaluated

A number of sociodemographic and disease factors were chosen as predictors of change in HRQOL. It is common practice to include a measure of physical disability as a predictor of HRQOL. The physical disability measure that was part of the NARCOMS Registry questionnaire was highly intercorrelated with the PCS summary score, and there was a high similarity of items. We deemed it to be measuring the same concept as the PCS and chose to exclude it from the analysis. Another commonly used factor is disease subtype (relapsing-remitting or progressive). Disease subtype was not available in the NARCOMS Registry database, but data on the number of relapses experienced were available and were used as an indication of the progression of the disease. The following 11 factors were included in the analyses:

Duration since disease diagnosis was calculated in years from the date of diagnosis provided by the patient and the date of the baseline survey.

Age at diagnosis was provided in years by participants at baseline.

Gender was a dichotomous variable.

Marital status was a multi-item checklist that was recoded into a dichotomous variable indicating whether the respondent was married/partnered at baseline or not.

Education level was a 5-point ordinal scale with higher scores indicating higher education at enrollment (categories: <12 years, high school diploma, associate's degree, bachelor's degree, postgraduate education).

Employment status was a dichotomous variable that indicated whether the respondent was employed at baseline or not.

Income was a 5-point ordinal scale with higher scores indicating higher income at baseline (categories: <$15,000, $15,000–30,000, $30,000–50,000, $50,000–100,000, >$100,000).

Number of emergency department visits was a single item asking patients to indicate the number of emergency room visits in the previous 6 months at baseline.

Number of relapses experienced was a single item asking patients to indicate the number of relapses they had experienced in the previous 6 months at baseline.

Number of prescription medications taken for MS symptoms was a multi-item checklist asking patients to indicate the type of medication they were currently taking for MS symptoms. The total number of medications was derived from the checklist at baseline.

Receiving a disease-modifying therapy (DMT) was a multi-item checklist asking patients to indicate the type of medication used in the previous 6 months. A dichotomous variable indicating receipt of any DMT was derived from the checklist at baseline.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample and overall data. To address the question of whether MS patients experience a change in HRQOL over time, repeated-measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to assess change in participants' baseline and 5-year PCS and MCS scores separately. Since this was not an inception cohort, duration since disease diagnosis was used as a covariate.

The sample was grouped, post hoc, into MS participants who indicated a clinically significant decline in their HRQOL and those who did not. To address the question of what baseline factors may be related to deterioration in HRQOL, two multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) were performed separately for the PCS and MCS change scores. Eleven factors were entered into each of the equations, with baseline HRQOL scores as covariates: duration since disease diagnosis, age at diagnosis, gender, marital status, education level, employment status, income, number of emergency department visits, number of relapses, number of prescription medications, and receiving a DMT. All dichotomous variables were coded as 0 and 1 for the analyses. All analyses were considered significant at an alpha level of .05. The Bonferroni method was used for all post hoc comparisons.

Results

Sample Description

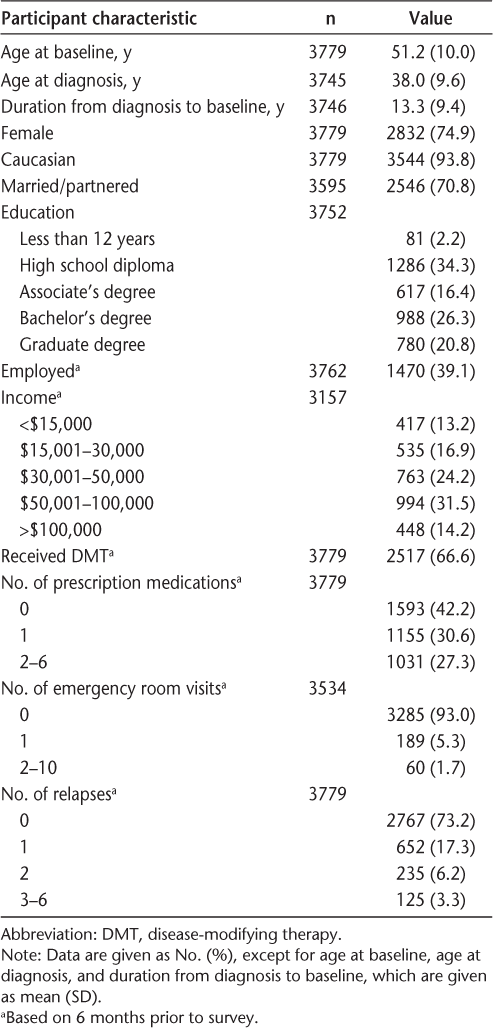

The sample consisted of the 3779 Registry participants who responded to the fall 2003 and fall 2008 surveys. Most participants were female, Caucasian, married, educated to the postsecondary level, and unemployed (Table 1). The average age was 51 years, and the average duration from disease diagnosis to the baseline assessment was 13 years, ranging from 0 to 59 years. The characteristics of this sample are similar to those in other studies using the NARCOMS Registry,20 as well as to reported characteristics of those with this chronic condition.

Baseline participant characteristics for entire sample (N = 3779)

HRQOL over 5 Years

The baseline and 5-year mean scores for the PCS and MCS are shown in Table 2. Overall, the PCS baseline scores for the sample were just over 1 standard deviation lower than those of the 1998 general US population, while the MCS baseline scores were slightly above the general population average.17 Results of the ANCOVA indicated a statistically significant decline over 5 years in mean PCS scores (F 1,3516 = 29.89, P < .01) with no interaction effect between PCS scores and duration since disease diagnosis (F 1,3516 = 0.77, P = .38). Although statistically significant, the mean change in PCS scores was not clinically significant (<3 points). There was no statistically or clinically significant difference in mean MCS scores (F 1,3516 = 0.18, P = .67), and no interaction between MCS scores and duration since disease diagnosis (F 1,3516 = 0.14, P = .71). Overall, the results indicated that, as a group, MS patients did not experience change in the HRQOL over a 5-year period. Since no change was found over time, analysis of factors related to change in HRQOL was not conducted for the sample as a whole.

Mean (standard error)a HRQOL at baseline and 5 years

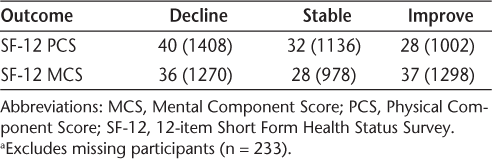

Although there were no clinically significant mean changes in HRQOL for the sample as a whole, individual changes had been observed. We chose to explore the concept of change over time beyond the initial design of the study, and reorganized the participants into groups based on clinically significant changes of 3 or more points on the PCS and MCS between baseline and 5-year scores (Table 3). Based on the idea that HRQOL is negatively associated with health-services use and health-care costs,21 22 the participants were placed into two groups to compare those who declined with those who did not. The resulting PCS groups consisted of the following: 1a) no decline (<3 points decline, no change, or improvement), 60% of sample; and 1b) decline (≥3 points decline), 40% of sample. The MCS groups consisted of the following: 2a) no decline, 64% of sample; and 2b) decline, 36% of sample.

Percentage (frequency) of sample showing change or stability of PCS and MCS scores over a 5-year period (N = 3546a)

Factors Affecting Change in HRQOL

Further analyses were conducted on the decline and no decline groups. Univariate comparisons indicated that the groups significantly differed on their baseline PCS (F 1,3544 = 165.61, P < .00) and MCS scores (F 1,3544 = 289.05, P < .00), respectively, with the decline groups reporting higher mean (SD) baseline scores than the no decline groups (PCS = 42.60 [8.94], MCS = 55.15 [7.72] vs. PCS = 38.10 [10.93], MCS = 49.89 [9.39]). Previous literature10 indicated that baseline scores are significant predictors of later HRQOL and would require control in order to examine the relationships of other sociodemographic and disease characteristics. Therefore, a decision was made to include baseline PCS and MCS scores as covariates in the multivariate analyses.

Physical HRQOL

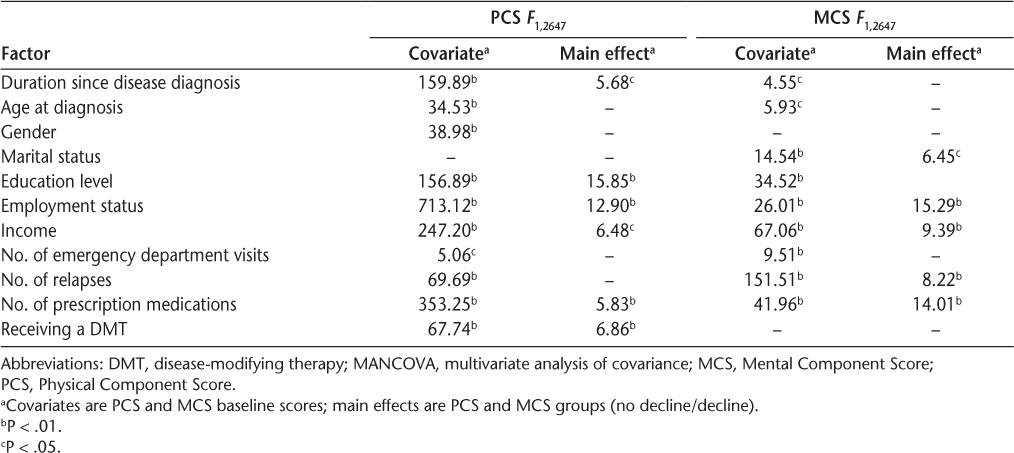

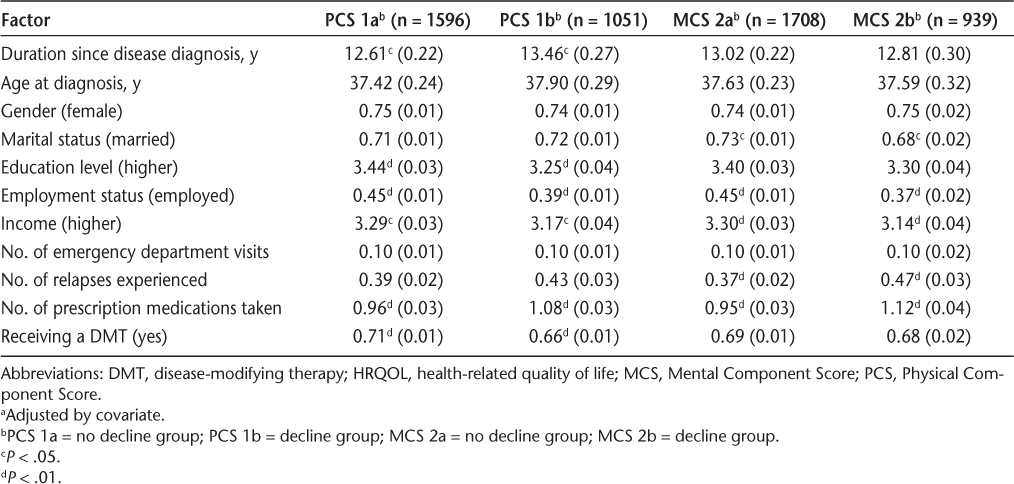

Results of the physical HRQOL analysis indicated that the covariate, PCS baseline scores, was significantly related to gender, education, duration since disease diagnosis, age at diagnosis, number of relapses, number of emergency department visits, employment status, income, receiving a DMT, and number of prescription medications (Table 4). Therefore, the final model was based on adjusted means after controlling for PCS baseline scores (Table 5).

Statistically significant F values of the MANCOVAs for PCS and MCS groups

Mean (standard error)a HRQOL for PCS and MCS groups

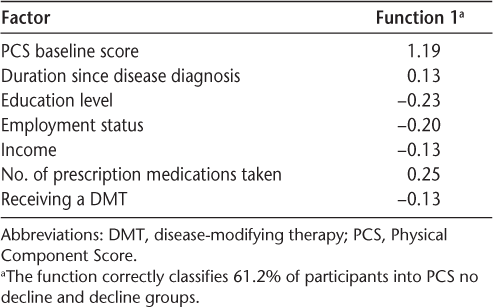

After controlling for baseline scores, having a lower education, having greater duration since disease diagnosis, not being employed, having a lower income, not receiving a DMT, and taking a greater number of prescription medications were significantly associated with a clinically significant decline in physical HRQOL.

To assess the strength of the factors in predicting decline in physical HRQOL, the MANCOVA was followed by a discriminant function analysis, using only the factors significant in the MANCOVA plus the covariate. Results indicated that there was one statistically significant factor that explained the differences between the PCS no decline and PCS decline groups: the PCS baseline score (Λ = 0.94, P < .01). Table 6 shows the standardized canonical discriminant function coefficients, with larger values indicating greater contribution of the factor to the distinction between the groups.

Standardized canonical discriminant function coefficients for PCS no decline and decline groups

Mental HRQOL

Results of the mental HRQOL analysis indicated that the covariate, MCS baseline scores, was significantly related to marital status, education, duration since disease diagnosis, age at diagnosis, number of relapses, number of emergency department visits, employment status, income, and number of prescription medications (Table 4). Therefore, the final model was based on adjusted means after controlling for MCS baseline scores (Table 5).

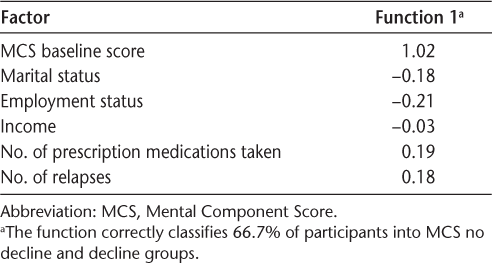

After controlling for baseline scores, not being married/partnered, experiencing a greater number of relapses, not being employed, having a lower income, and taking a greater number of prescription medications were significantly associated with a clinically significant decline in mental HRQOL.

To assess the strength of the factors in predicting decline in mental HRQOL, the MANCOVA was followed by a discriminant function analysis, using only the factors significant in the MANCOVA plus the covariate. Results indicated that there was one statistically significant factor that explained the differences between the MCS no decline and MCS decline groups: the baseline MCS score (Λ = 0.92, P < .01). Table 7 shows the standardized canonical discriminant function coefficients, with larger values indicating greater contribution of the factor to the distinction between the groups.

Standardized canonical discriminant function coefficients for MCS no decline and decline groups

Discussion

The results of this study showed that the sample as a whole did not experience any clinically significant change in their HRQOL over the 5-year study period. This finding is similar to that of a 2-year longitudinal study by Hopman et al.,13 who found that scores on the SF-36 changed minimally over time and did not reach clinical significance for 288 MS patients. The current study did, however, find substantial variation in individual patients' reported HRQOL over time, with approximately 40% and 36% declining in the PCS and MCS, respectively, 32% and 28% remaining stable, and 28% and 37% improving. Similarly varied results have been found in other studies reported in the literature.3 10–12 For example, Solari et al.11 examined perceived HRQOL in 205 people with MS over a 5-year period and found that overall, health status declined, with worsening in both general health and physical function. In contrast, social function, mental health, and health distress improved. McCabe et al.3 found both improvement in global HRQOL and no change in physical or psychological HRQOL over a 2-year period in a sample of 386 MS patients.

In order to further explore the variations noted in HRQOL, we chose to examine the relationships between sociodemographic and disease factors and the different groups of MS patients—those who declined compared with those who did not decline. A clinically significant decline in physical HRQOL was reported for 40% of the sample over a 5-year period, while a clinically significant decline in mental HRQOL was reported for 36%. Generally, those who declined had better physical and mental HRQOL at baseline than those who did not, and baseline HRQOL scores were significantly related to many of the factors used in the multivariate analyses. This finding is similar to the results of an 8-year follow-up study by Miller et al.,10 who found that baseline physical and mental HRQOL scores are significant predictors of follow-up HRQOL. Using baseline scores as covariates in the current study removed the influence of this factor on the outcome, allowing us to focus on the other sociodemographic and disease factors. The current study found that MS patients who have had the disease for a longer period of time, have a lower education level, are not employed, have a lower income, are not receiving a DMT, and are taking a greater number of prescription medications are more likely to experience decline. It is not surprising that, as the disease progresses, physical HRQOL declines. Those with lower education levels may have fewer resources available to them to help them cope with the progression of the disease. Although related, not being employed and having a lower income are likely the result of progression of the disease. Patients may reduce their work hours or stop working because of the limitations of the disease. Although patients were not asked why they were not receiving a DMT, it seems likely that they are not receiving the benefits that the medication may have to offer. A greater number of prescription medications—many of them antidepressants and pain relievers—may indicate greater difficulties with the physical consequences of MS.

In terms of mental health, not being married/partnered, experiencing a greater number of relapses, not being employed, having a lower income, and taking a greater number of prescription medications were significantly associated with a decline over 5 years. Certainly the social support offered by a partner could be a mediating factor in coping with MS.23 A greater number of relapses can influence mental health as patients experience more sudden changes in their functioning.24 Not being employed and having a lower income may result from poorer mental health, and changes in employment may contribute to income loss. Alternatively, having a lower income may increase stress related to financial problems and expenses resulting from adapting to the disease, contributing to a decline in mental HRQOL.25

This study has both strengths and limitations. The large sample size and 5-year span of assessment provide a broader picture of the HRQOL and disease status of MS patients in North America than did previous studies and provide substantial statistical power for the analyses. The sample was not an inception cohort, and the number of newly diagnosed patients in the Registry was too small to complete the analyses required in this subgroup. In order to compensate for this, the duration since disease diagnosis was used as a factor in the analysis. The sample was composed of volunteers and was not random. Therefore, it is possible that the Registry participants are not representative of all patients with MS in North America. However, this study does provide an initial indication of how MS patients who volunteer to be part of a national registry may fare over time with regard to their HRQOL. Another limitation of the current study was the use of a generic HRQOL tool instead of an MS-specific tool. It is recognized that an MS-specific HRQOL tool may be more responsive to small changes in MS disease course.16 26 However, since this was not a clinical intervention study, the examination of larger changes over a 5-year period was sufficient. Finally, the decision to explore differences between groups of participants based on change in scores was not part of the original study design and lends itself to exploratory research. It is recommended that a prospective cohort study, following a random sample of patients from time of first contact with various MS centers across North America, be conducted to allow for further exploration and testing of this study's findings. Future studies may also include an MS-specific HRQOL tool to capture concepts more specific to the disease.

MS affects many young adults and their families and places their HRQOL at risk. The findings from this study are encouraging—most patients experience stability or improvement in their HRQOL over time, and sociodemographic and disease-related factors appear to contribute minimally to HRQOL decline. Adaptive coping strategies, social support, and psychological adjustment27 have been cited in the research literature as important concepts in maintaining or even improving HRQOL.28–30 Thus, those factors not amenable to change, such as gender, age, and disease duration, along with those factors challenging to modify, such as employment, relapses, and medications, may not be the major influences on HRQOL outcomes.31 The major influences may be those factors amenable to change, such as coping, support, and resiliency.28–30 Clinicians can relay a message of hope to patients with regard to their future HRQOL. The trajectory of their HRQOL does not have to mirror the trajectory of their disease. The factors that both clinicians and patients cannot change and the factors that are difficult to modify do not need to be the focus of HRQOL interventions. Helping patients cope and connect better, early on in their disease course, may be the best way to influence HRQOL.32 As with the majority of interventions in MS care, early intervention focusing on what can be done rather than on what cannot be done will facilitate a stable HRQOL over time.

PracticePoints

About 60% of MS patients are able to maintain a stable health-related quality of life (HRQOL) over a 5-year period.

Patients most likely to experience deterioration in both physical and mental HRQOL are those who have better HRQOL to begin with.

Sociodemographic and disease characteristics appear to play a minor role in whether patients will experience deterioration in HRQOL over time.

Preventing, or at least minimizing, HRQOL decline in the early stages of the disease may be the best way to ensure high levels of HRQOL over time.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Tuula Tyry, Program Manager with the NARCOMS project.

References

Wu N, Minden WN, Hoaglin DC, Hadden L, Frankel D. Quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis: data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. J Health Hum Serv Admin. 2007; 30: 233–267.

Hopman W, Coo H, Edgar C, McBride E, Day A, Brunet D. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007; 34: 160–166.

McCabe M, Stokes M, McDonald E. Changes in quality of life and coping among people with multiple sclerosis over a 2 year period. Psychol Health Med. 2009; 14: 86–96.

Alshubaili A, Ohaeri J, Awadalla A, Mabrouk A. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a Kuwaiti MSQOL-54 experience. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008; 117: 384–392.

Casetta I, Riise T, Nortvedt MW, et al. Gender differences in health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2009; 15: 1339–1346.

Sprangers M, de Regt E, Andries F, et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000; 53: 895–907.

Turpin K, Carroll L, Cassidy J, Hader W. Deterioration in the health-related quality of life of persons with multiple sclerosis: the possible warning signs. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 1038–1045.

Dilorenzo T, Halper J, Picone M. Quality of life in MS: does aging enhance perceptions of mental health? Disabil Rehabil. 2009; 31: 1424–1431.

Schwartz C, Frohner R. Contribution of demographic, medical, and social support variables in predicting the mental health dimension of quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis. Health Soc Work. 2005; 30: 203–212.

Miller D, Rudick R, Baier M, Cutter G, Doughtery D, Weinstock-Guttman B. Factors that predict health-related quality of life in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 1–5.

Solari A, Ferrari G, Radice D. A longitudinal survey of self-assessed health trends in a community cohort of people with multiple sclerosis and their significant others. J Neurol Sci. 2006; 243: 13–20.

Hopman W, Coo H, Brunet D, Edgar C, Singer M. Longitudinal assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2000; 2: 15–26.

Hopman W, Coo H, Pavlov A, et al. Multiple sclerosis: change in health-related quality of life over two years. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009; 36: 554–561.

NARCOMS. NARCOMS: About Us. http://narcoms.org. Accessed March 5, 2012.

Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T. Substantial adverse association of visual and vascular comorbidities on visual disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011; 17: 1464–1471.

Norvedt MW, Riise T. The use of quality of life measures in multiple sclerosis research. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 63–72.

Ware J, Kosinsk M, Turner-Bowker D, Gandek B. User's Manual for the SF-12v2 Health Survey (With a Supplement Documenting SF-12 Health Survey). Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Inc; 2007.

Ware J, Kosinsk M, Keller S. SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. 3rd ed. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Inc; 1998.

Gruenewald DA, Higginson IJ, Vivat B, Edmonds P, Burman RE. Quality of life measures for the palliative care of people severely affected by multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2004; 10: 690–725.

Marrie R, Cutter G, Tyry T. Cumulative impact of comorbidity on quality of life in MS. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012; 125: 180–186.

Henriksson F, Fredrikson S, Masterman T, Jönsson B. Costs, quality of life and disease severity in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study in Sweden. Eur J Neurol. 2001; 8: 27–35.

McCrone P, Heslin M, Knapp M, Bull P, Thampson A. Multiple sclerosis in the UK: service use, costs, quality of life and disability. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008; 26: 847–860.

Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. A review of psychological correlates of adjustment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009; 29: 141–153.

Orme M, Kerrigan J, Tyas D, Russell N, Nixon R. The effect of disease, functional status, and relapses on the utility of people with multiple sclerosis in the UK. Value in Health. 2007; 10: 54–60.

Aronson K. Quality of life among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Neurology. 1997; 48: 174–180.

Riazi A, Hobart JC, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, Thompson AJ. Evidence-based measurement in multiple sclerosis: the psychometric properties of the physical and psychological dimensions of three quality of life rating scales. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 411–419.

O'Doherty L, Hickey A, Hardiman O. Measuring life quality, physical function and psychological well-being in neurological illness. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 2010; 11: 461–468.

Goretti B, Portaccio E, Aiplili V, Razzolinii L, Amato M. Coping strategies, cognitive impairment, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2010;31(suppl 2):S227–S230.

Parkman K, Cox S. The dimensional construct of benefit finding in multiple sclerosis and relations with positive and negative adjustment: a longitudinal study. Psychol Health. 2009; 24: 373–393.

Phillips L, Stuifbergen A. The influence of positive experiences on depression and quality of life in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Holistic Nurs. 2008; 26: 41–48.

Miller D, Rudick R, Hutchinson M. Patient-centered outcomes: translating clinical efficacy into benefits on health-related quality of life. Neurology. 2010;74(suppl 3):S24–S35.

Yorkston K, Johnson K, Klasner E. Taking part in life: enhancing participation in multiple sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2005; 16: 583–594.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Marrie is a scientific director with NARCOMS. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: The Northern Alberta MS Patient Care & Research Clinic provided funding for this study.